Worlds Changed at the Computer Game Developers Conferences of 1988

Explorers in uncharted lands

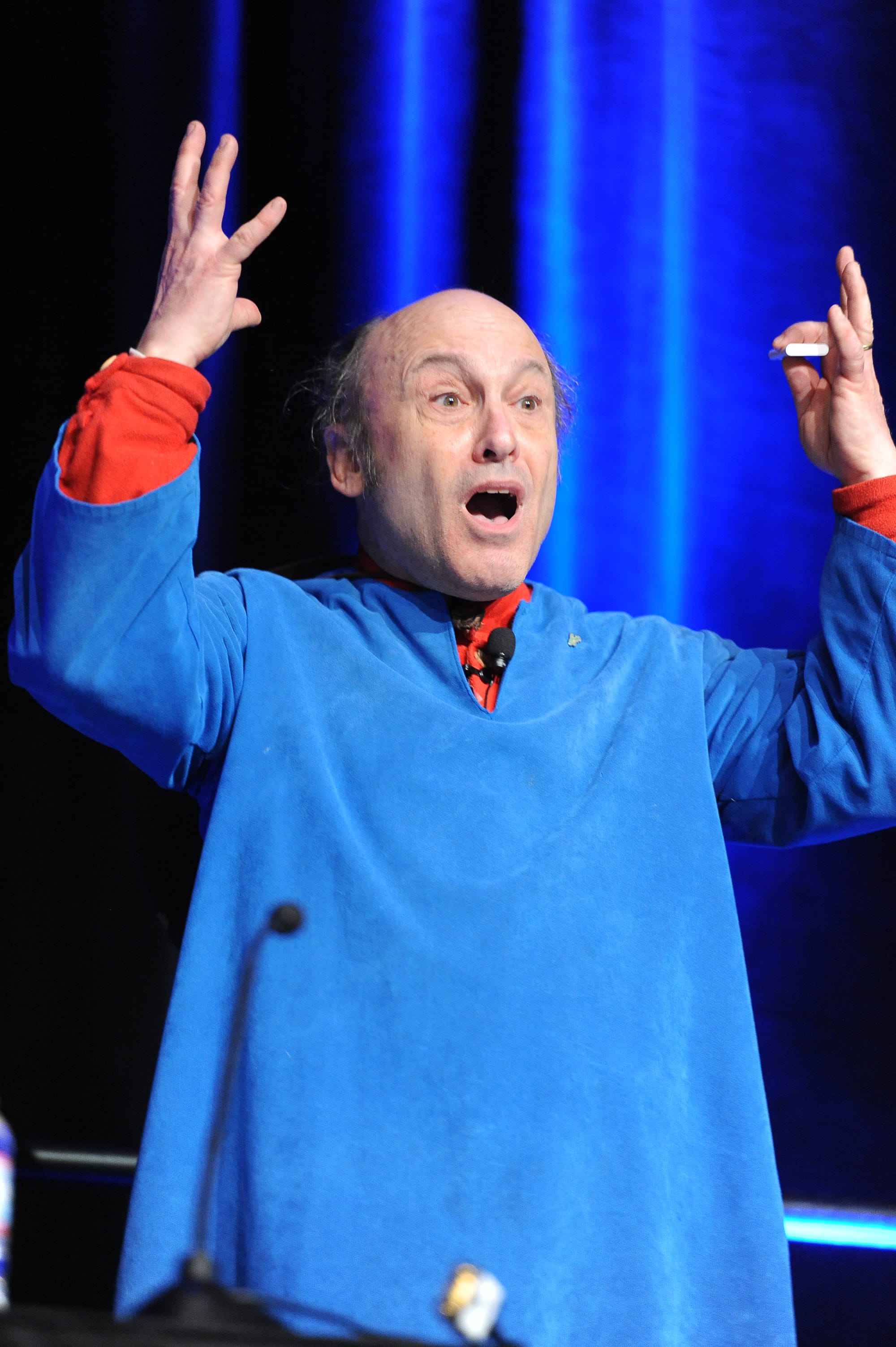

The video game industry pieced itself together after the crash of 1983. Developers, even though they had hope in their hearts, worked in isolated pockets of creativity. They often learned their craft in tiny teams, or even as solitary developers. During that time, one game designer with a physics background, Chris Crawford, explored ideas to connect these fragile islands.

Thoughts of a path

While the industry still struggled, in 1984, Chris Crawford published what many recognize as the first true game development manual, The Art of Computer Game Design. By that time, he had already worked as a programmer on projects such as Eastern Front (1941) and Tanktics, and also in other roles including writer and game designer. It was no understatement to say he thought about game design from various angles.

The Journal of Computer Game Design became a forum for Crawford to share his views from 1987 onwards. Other authors also contributed to its pages, which triggered the idea of a physical conference, where game developers could exchange their thoughts in real-time. Crawford informed his readers of his plan.

In April 1988, the 27 souls traveled up a mountain road near San Jose to reach the conference hall — Crawford’s own home. He had ordered a massive sub sandwich from a deli to satiate their collective hunger. This was, above all, a meeting to satisfy an intellectual hunger, though.

Excited attendees could at last uncork the various thoughts they could not share with outsiders. They talked about their profession, which some believed would create ubiquitous entertainment in the future. The people who joined Crawford at this mountainside meeting included Brian Moriarty (already an author of several interactive fiction titles), Brenda Laurel (a trailblazer in the academic discussion over interactive storytelling), Gilman Louie (who, at a young age, had founded a game company that had already merged with Spectrum Holobyte), and many other deep thinkers who would leave deep imprints in the industry in their own ways.

Another round of encounters

Attendees of the first Computer Game Design Conference were not ready to let the phenomenon die after only a single meeting. More than knowledge had been exchanged that day. During the discussions, they realized that other people also had the same hopes for their new corner of the creative arts.

That same year, people came together again, but now at a Holiday Inn in Milpitas, for a second conference. Around 4 times more people attended than the first instance, listening to various speakers and also asking pointed questions.

The organizers also gave awards, although he chose not to include a category for developers because it could lead to conflict. Among the winners was Electronic Arts, who won the best Technical Support award. Most attendees were not fans of console games, since many of them were PC developers who specialized in simulation and strategy games. According to the Journal of Computer Game Design, discussions turned to a new title, though:

One Nintendo game, Zelda, was given grudging respect, because it was considered to transcend the limitations of the Nintendo system. (No one argues that the title itself will be a fixture in home entertainment. Rather, the question is whether the best-selling games are precursors of a significant computer game sub-genre).

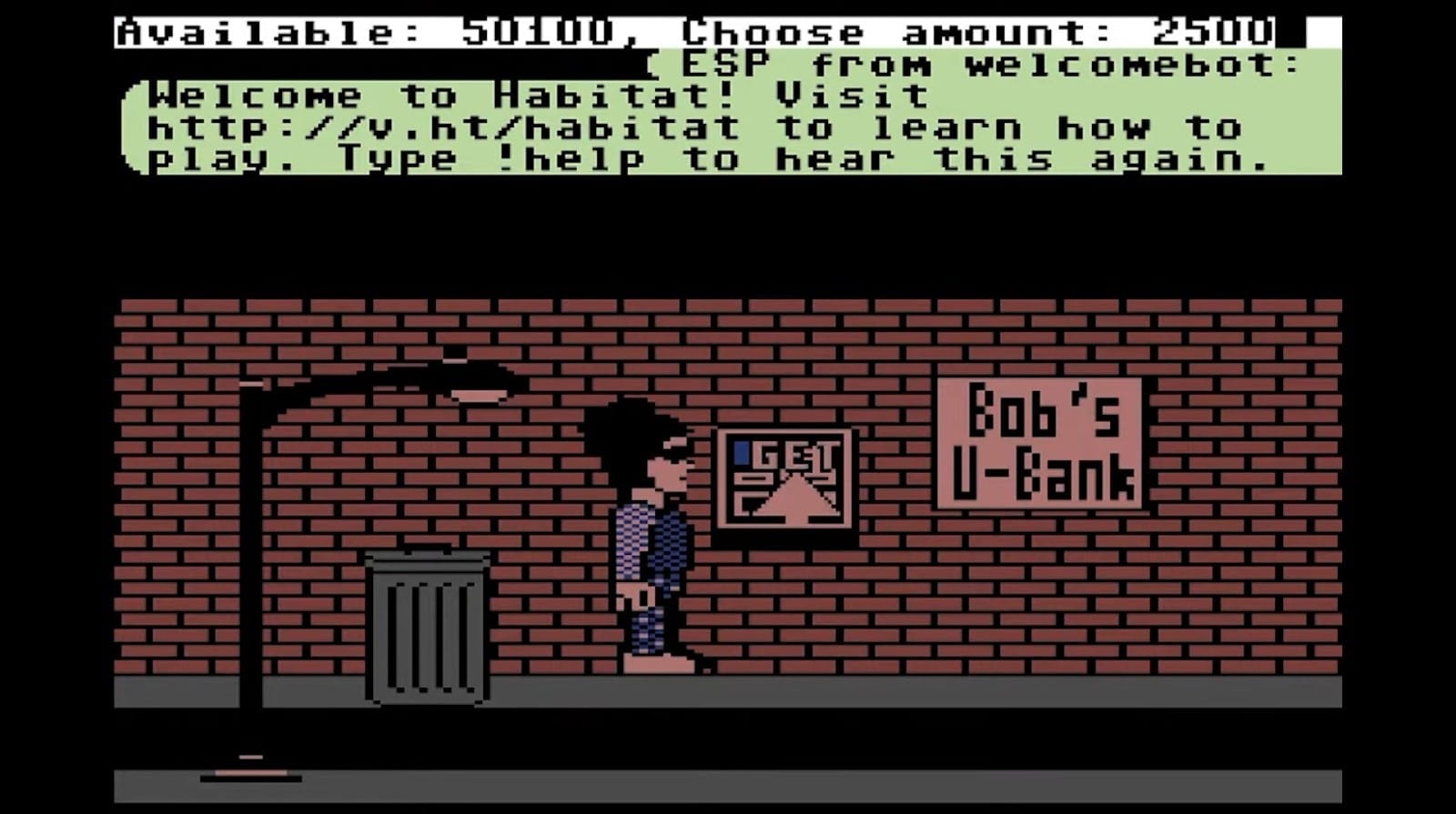

Many popular PC games at the time were famous for their considerable depth, like Ultima and Might and Magic, so some wondered if the new action-oriented console titles would dominate the market. Sales figures as a measure of success were already a topic, too. Certain attendees looked to the future, like when those who specialized in multiplayer games talked about the possibilities of using modems to connect players in games. Habitat, a game that was in beta by 1986, had been one of the first to venture into these waters.

Seen from a side

The board of the Computer Game Design Conference, which later became Game Design Conference, ousted Chris Crawford as chairperson because they opposed his non-profit vision for the convention. A company, Miller Freeman, bought the organization soon after that.

Chris Crawford could already see the swells of the changes in game development. At CGDC 1993, he spoke about how the supreme goal he wanted to achieve was a fearsome dragon, leading it to become known as the Dragon Speech. This signaled his break from the ranks of mainstream game developers.

Afterward, Crawford continued to write about storytelling and discuss concepts with others. In the 2000s, he held conferences at his home, called Phrontisterion, to foster intellectual exchanges once again. Phrontisterion VI, held in 2005, was the last of these events. He also worked on Storytron, a program that allows users to create interactive stories.

The Game Developers Conference grew in a different direction in the meantime. Nowadays, it’s one of the largest events on the gaming industry’s calendar. To get an idea of the scale, one need only look at the total number of attendees of 2023’s version, which logged in at a staggering 28,000.

Sprints to a destination

The Game Developers Conference’s early history is the tale of the video game industry. As the conference expanded, development teams expanded, so that games specialized to make specific actions more complex thanks to the extra processing power, the size of the development teams, and the increased investments.

What was lost in the process was the breadth of emotional experiences that Crawford identified in his Dragon Speech. More and more, popular games focused on inserting fun into actions, but the characters or storytelling did not always receive the same level of attention. A version of the Hero’s Journey established itself as the de facto model for most games because the marketplace rewarded its stories.

The rise of indie games in the mid-2000s expanded the breadth of experiences and story models. Through these games, we have become an immigration officer, a miner of blocks, and even a goose that collects items. Once again, the smaller team dynamic allows an auteur to have a more direct hand in all facets of the creative process.

Now people talk of video games as art — the move to view them as such began in earnest at the early Computer Game Developers Conferences. Many dreams of the attendees remain unrealized. The video game, as an art form, is still young though. To foster its growth, it’s wise to take heed of the warnings of those who opened everyone’s eyes.