Why Final Fantasy Shines Brightest as an MMO

The crystals were inside us all along

Final Fantasy is a series that’s tough to pin down. Just about every form of popular media and genre has a Final Fantasy, and their subjects and stories are rarely more than superficially related. Whoever you are, there’s almost certainly a Final Fantasy for you.

From RPGs to action games to movies and anime, you could make a case that Final Fantasy is a one-size-fits-all, jack-of-all-trades IP. But the true spirit of the series is captured by its most controversial chapters: the massively multiplayer online games, XI and XIV.

The decision to anoint them with those glittering Roman numerals, canonizing them in the hallowed halls of mainline Final Fantasies, is where the lines are drawn in this nearly 20-year-long disagreement. Spin-offs can be ignored, but XI and XIV can’t and that’s a completionist’s worst nightmare.

It even created rifts within the Square, Final Fantasy’s parent company, with series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi butting heads with president Yoichi Wada. When it came time to christen their new online Final Fantasy, Sakaguchi insisted on the XI, while Wada resisted it. Hiromichi Tanaka, a producer on Final Fantasy XI dished the dirt in a recent interview.

"Then when we were deciding whether to call [Final Fantasy XI] “FF Online” or release it as a numbered entry in the series, Mr. Sakaguchi adamantly believed it should be released as a numbered entry. He insisted that a game with a name like “FF World” would be viewed as a spin-off rather than a main entry in the FF series, which led to a debate between him and management[…]

Management wanted to revoke its place as a numbered entry later on because they feared many players would be unable to play the game, as it required purchasing additional hardware on top of the PS2 console."

Hiromichi Tanaka

So it’s understandable that many of Final Fantasy’s long-time fans felt suddenly gated out of something they’ve loved and supported for decades. Requiring a stable internet connection (not always a guarantee in 2002 when XI came out), more expensive hardware, and, worst of all, a monthly fee, there was a strong case for relegating these games to the spinoff table.

While the tensions have largely cooled as the world has begrudgingly accepted that these games are canonical to the series, XI and XIV are still often omitted from rankings and “Best Of” lists featuring Final Fantasy games. They’re the black sheep of the series even as XIV climbs to the third most popular active online game in the world.

An online Final Fantasy was a project that was too big too fail

So why did Final Fantasy’s creators insist on grouping the online entries with the other mainline games? On paper, it’s easy to argue that an online game is only as successful as its enrolment numbers, and those Roman numerals would do a lot of that heavy lifting early on.

It’s a steep climb to get enough people to pay monthly for a spin-off that could putter out and die in a year or two. A mainline entry conveys confidence and commitment from the developers.

Also consider the massive financial and developmental resources required to see the project through. Spin-offs are typically lower-budget fan service cash-ins and Square was bringing its A-game (and budget) with XI. Total development costs for the project are estimated at around 20 million US dollars. By comparison, Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, the best selling game of 2002 and Rockstar’s most expensive game to date, cost just $5 million to develop.

While these arguments might make sense in black and white, Sakaguchi was seeing something else entirely — something that would take the rest of Square much longer to realize.

Let’s go back to the start of it all: the original Final Fantasy. Released at the end of 1987 for the NES, it was a game about exploring a new world via the characters on screen, the Warriors of Light, as our avatars. The story was second to the experience. And the experience was unique to each player. You were free to forge your own path.

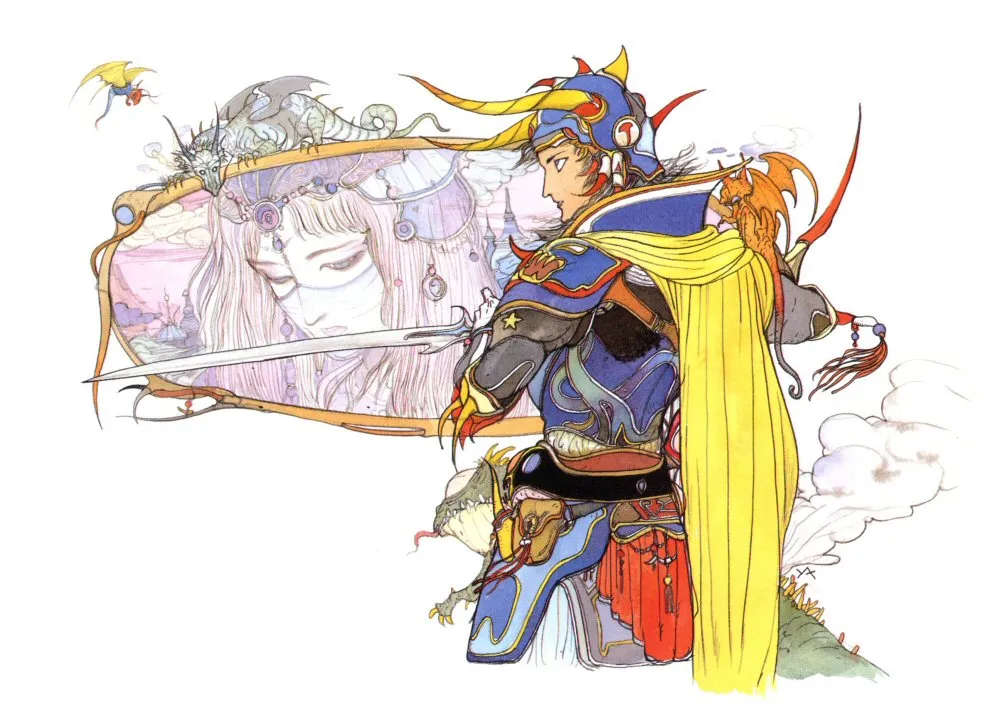

The Warrior of Light

In the long history of Final Fantasy, only three main titles start off in a similar vein, with no pre-written main character: the online games XI and XIV, and of course, FFI. In each of these games, you start as a blank slate: no history, goals, or personality. You don’t even speak. You simply choose your name, your job, your fighting style, and then enter the world as yourself and follow your new destiny to greatness.

Perhaps by making the Warriors of Light newcomers to the Kingdom of Corneria in FFI, without ever addressing where they came from or who they were before, Sakaguchi was seeking to canonize the player in the story of the game.

All three titles also featured “chosen one” stories. It’s a trope as old as time, and Final Fantasy has leaned into it from day one. And it’s a wonderful way to include the player in the game’s world. In each of these games, we play a mysterious outsider, uniquely blessed by “the crystal,” and called to answer the cries of a world in pain.

Who could be more special in an 8-bit 2-dimensional game than the player holding the controller and dictating the action on screen from a higher dimension? The Warriors of Light appeared in the game at the same instant I pressed the power button on my Nintendo. Coincidence? Okay, so maybe that’s a little on the cheesy side, but I think there’s something to it.

It’s that spirit that made the move into the online world such a natural, and almost predetermined one. To actually make the player into a Warrior of Light, a newcomer to a living, breathing and constantly changing online world, is as Final Fantasy as Final Fantasy gets. It’s why Hiromichi Tanaka called Final Fantasy XI “the most representative title of the Final Fantasy series” in a 2007 interview.

Arming us with exceptional abilities and bringing us into a bustling land filled with millions of other Warriors of Light with whom to connect is the most fitting realization of Sakaguchi’s original vision for Final Fantasy.

When the stories took over

It would be a long time before Square would be able to make that leap to the online realm. You could even say that the series did an about face and barrelled headlong in the opposite direction instead.

With the very next game and the eight that followed that one, Square and Sakaguchi set out to tell more structured tales. Characters got names and personalities. They had histories and motivations. The worlds grew lush with life and culture. They became more a vehicle for telling a story than creating one.

It seemed a natural progression to go from wordless pixel marionettes to fleshed out people with full character arcs. And it worked. Final Fantasy has told some of the most memorable and iconic stories in gaming history. It’s heroes are recognizable even by people who don’t know what Final Fantasy is.

But in that transition, Final Fantasy lost something. Sure, you could say that it gained much more, but it lost part of what made that first game so personal to the player. We went from being the hero to playing a character. The stakes are lighter with that additional degree of separation, and so are the motivations.

Final Fantasy would go on in this way, and be lauded and rewarded for it. Square would learn a lot over the first ten games and become leaders in gaming technology. Final Fantasy VII is credited as the first triple-A video game. It started an arms race to make bigger, better, and more cinematic games among the world’s top developers. It changed the gaming landscape forever.

It also gave Square an enormous amount of cash which allowed them to take each subsequent game to a higher level. FFVIII got a theme song performed by an international pop star. FFX made the jump to fully voiced characters in both Japanese and English. And with XI, Sakaguchi began to think of his original intent with the first Final Fantasy once again.

Back to where we started

Now a technological powerhouse and household name, Square had the means to make it’s “most representative Final Fantasy” into reality, and to make us, the players, the hero in their story once again. Despite that pesky roman numeral, fans showed up in droves. Square recouped that $20 million development cost for the game and online network by 2003, just one year later.

Final Fantasy XI went on to have over 500,000 active subscribers by 2008 and became the most profitable Final Fantasy title ever. It was only surpassed in 2021 by Final Fantasy XIV, which currently hosts over 24 million active subscribers.

Give its current success, it’s hard to see an online Final Fantasy as the massive gamble that it started out as. But at the time, they couldn’t even decide what to name the game for fear that the wrong title could spell ruin for the project and possibly the entire company. Every decision was weighed very carefully.

But Hironobu Sakaguchi was right all along. He had his finger on the pulse of what Final Fantasy was about and what it means to players better than anyone at Square. It’s easy to get bogged down with financials and logistics only to lose sight of the spirit of a project and how it connects with its audience, but Sakaguchi had his eye on the ball the whole time.

Final Fantasy has grown and changed and branched out so much since that first game 25 years ago that everyone has a different idea of what it actually is and what it means. Its definition constantly changes depending on who is observing it.

And that is precisely what makes Final Fantasy, well, Final Fantasy. It is all those things at once and none of them at all. It’s about the personal connection to you, the player. And Final Fantasy XI and XIV are the digital playgrounds that allow us to explore that connection and become a part of that world. They called us in from a distant land, blessed us with the light of the crystal, and sent us off to forge our own paths and create some fantasies of our own.