When Video Games Test Your Personality

Video games, morality, and quantifying personalities

Do you know that quiz you had to take in class at the beginning of Fallout 3? The one that ended up allocating your skill points? What would it take for it to actually predict your personality? I always thought they were a really creative way for you to pick your RPG build. It made me think of hidden mechanisms in other games that “tested” your personality. There’s one in Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, where you're asked multiple choice questions of hypothetical scenarios that decide which type of Jedi you are. But this and the one in Fallout don’t really matter. Like real-life career aptitude tests you take in school, they’re not destiny, and you can end up in a completely different work field. Despite whatever result you get from the Fallout 3 quiz or the Jedi training test, you can still rearrange your skill points and pick the lightsaber color that better suits your gameplay preferences. They’re really just set dressing for immersion.

Karma police

Even the karma system in Fallout 3, the one that tells you whether you’re a good person or not based on the game’s parameters, really only gives you quirky titles. You can choose to nuke an entire city or donate to a church, but they don’t necessarily mean you’re a good person in the game or in real life. Sure, some factions may shoot you on sight, and companions may like or dislike you based on what you do, but that’s about it. These actions all boil down to a numbers game, whether you’re assigned one label or another. Maybe what differentiates the social makeup of each person and what decides moral character cannot be quantified.

Besides, what separates in-game actions from real life are the incentives and positive reinforcements the game's inherent systems reward you with. Some games encourage you to do crazy things like nuke a city, while others will nuke you if you kill even one person, like in Death Stranding, made by famously anti-war Hideo Kojima. The way games are designed pushes certain behaviors while punishing others, having different etiquettes from reality. Outside our screens, what discourages problematic actions are social sanctions, along with the intrinsic guilt that most people feel when they hurt others. Players' tendency to feel the same things when holding a controller may vary from person to person.

Maybe what differentiates the social makeup of each person and what decides moral character cannot be quantified.

Fallout is set in a post-apocalyptic world where civilization has fallen through, in a way that means you won’t have to fear serving time if you break the law. With a splintered government existing under a Wild West-type system of laws, it’s no wonder that there are so many games with a post-apocalyptic setting. They allow the ultimate freedom of choice for players, letting them run amok in a sandbox where they can make and break as many castles as they want. Spontaneity is the name of the game. Besides, if you think you made the wrong decision, you can always roll back your save file; regret can be fixed with the press of a button. Video games allow you to make consequence-free decisions that wouldn’t be permissible or even rational in any other context.

Test-based games

If what you do in video games doesn’t reflect your real dispositions, is it even possible for a game to accurately test your personality? Well, there’s research that claims they can. A small game was designed for the test: In it, each action taken in the game is associated with The Big Five Personality Test. This means that how long the player solves a puzzle or how often they check their map can be correlated to their Conscientiousness, while how many areas they explore can be tied to Openness.

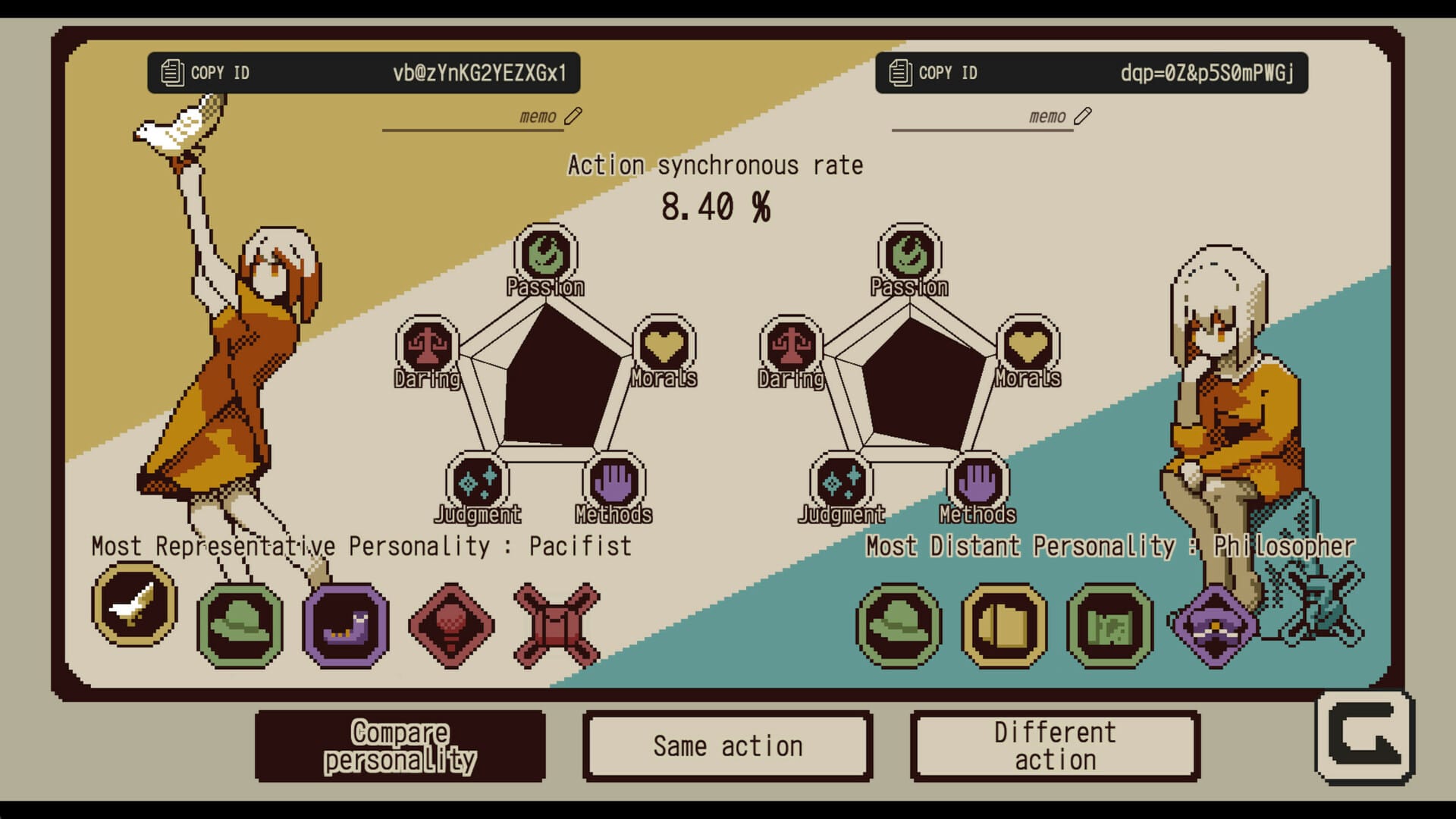

Refind Self: The Personality Test Game by developer Lizardry, released last year, is a game entirely built on the premise of being a personality test. In the game, you’re an android that struggles to “find” itself after the death of its maker. Here, you aren’t presented with questions in the form of text; instead, the game’s whole map is a quiz you answer through actions. It’s the previous research turned into a fully fledged game with a story and world. Your choosing to go to one place instead of the other is an answer to an invisible question. These actions are compiled into quantifiable data grouped behind the scenes and turned into a designated personality. Instead of The Big Five Personality Test, however, they made an entirely new group of labels, such as Researcher or Sage, that has more in common with classes in role-playing games. Nevertheless, it’s an interesting endeavor that makes for a unique experience, a game where you’re told you’re being analyzed from the beginning, reframing every action as vital.

Like the immensely popular MBTI personality test, part of the fun of these tests is comparing what you get with your friends, like whether you’re considered more empathetic or logical than the other. This makes it less of an accurate gauge of your personality, but more of a guesstimate of your tendencies. You can even replay the game to try and get all the options. It’s not a flaw on the game’s part that it doesn’t comprehensively lay out your personality, as only a reliably standardized psychometric measure could even come close to doing that. Fortunately, Refind Self also has a story you can explore and a little mystery you uncover through replay.

This emphasis on replayability and comparing statistics makes me think of the way Telltale sums up decisions in their games. At the end of each chapter, you see if you are in the minority or majority based on the choices you make, and how they impact the other characters’ opinion of you. The difference between this and, say Fallout, is the game’s entire selling point being its ability to simulate consequence. Where Fallout, especially the Bethesda-developed ones, leans heavier on the action side of the RPG, emphasizing violence and shooting mechanics, Telltale is able to allocate all its budget to its branching paths and character relationships. Its gameplay isn’t shooting, it relies on making choices, therefore its systems don’t encourage the player to keep themselves alive, it encourages them to make the right decisions according to their character.

Telltale's trolley problems

The tension felt when playing Telltale games stems from making hard choices, not from being afraid of restarting a level, but losing a non-playable character to whom you’ve grown attached. It tries its best to make your choices at least appear to have consequences, so you feel impassioned and responsible for them. It does this in a variety of ways: notifications reminding you of characters’ reactions to your actions, having to restart an entire chapter to retry your decisions, and being pressed for time on every choice. According to Dr. Linda Kaye, the result is a feeling of ownership and accountability to the player's character and their companions.

A crucial time-pressured decision may decide who lives or who dies. These gamified trolley problems make the statistics at the end all the more fun. This can lead to a sense of gratification when the game tells you that you’re part of the majority and you feel validated for your choice. It can also lead to serious reflection when you don’t. Because we are socially conditioned, a perceived wrong choice in the game can also make us rethink how we should act in real-life social or ethical situations. With systems that encourage taking choices seriously instead of experimenting like in a sandbox RPG, Telltale games may capture more of your personality than previous games. But with limited choices and few that truly matter long term, the endings can leave an impersonal taste as if a narrator is reading your tarot, something you don’t really have control over.

Because we are socially conditioned, a perceived wrong choice in the game can also make us rethink how we should act in real-life social or ethical situations.

Alternatively, Disco Elysium has a narrator that maybe gets a little too close for comfort. The critically acclaimed game has voices that describe things to you, and they come from your own thoughts; your reptilian brain and limbic system. Tied in that system, the game takes the concept of personality a bit further, with political alignment, how you can unlock certain thoughts that lead you to an idea that develops into an ideology. You can be a communist, fascist, centrist, or capitalist, with each commitment giving certain gameplay benefits. But picking one alignment doesn’t automatically mean that you internalize them in real life.

What it can do is lead to a willingness to know more about the different ideologies and what may lead people to believe in them. If anything, this gives players a chance to explore and understand themselves more if an alignment doesn’t feel right to them. Your interest in these topics can lead you to research more about their real-life equivalents.

Looking beyond labels

People aren’t binary, but sometimes it’s easier to believe that we’re only Paragon or Renegade, Brotherhood or Enclave, Communist or Capitalist, Introvert or Extrovert, Right or Left. In the realm of video games, that’s certainly easier to program. Even outside of it, it’s easier to understand people when labeled within groups. There are many of us, and maybe to see each one carrying an inner life takes too much space in our heads. So personality tests and political alignments are neural shortcuts that can give us an instant bond with strangers. Comparison causes connection, and even difference engages conversation, making you want to listen to others and vice versa. This can strengthen your self-image or reassure your self-esteem. We enjoy the validation we get when we meet strangers who also choose to save Ashley in Mass Effect 1. But do these define our personality? Do these in-game actions make us a good person?

We act more heroic when we have nothing to lose. When our currency is virtual, we can give it away. When only our virtual life is on the line, we can sacrifice it. But our choices in video games can also reveal who we want to be, and what we should strive to be. Both personality tests and video games can show an outsider’s perspective of oneself. Seeing yourself in a third-person view can rearrange your ideal self. And thinking of individual people three-dimensionally, as more than their labels, can make past assumptions obsolete.

Through video games, we can experiment and test the boundaries of ourselves, and discover to what degree our decisions are agreeable. If we try to be a fascist in Disco Elysium, maybe we feel bad afterward, and that reifies our pre-existing beliefs. Or maybe we blow up Megaton and don’t feel a thing because, in the end, these are not real people, they’re actors in a playground for us to role-play and experience different outcomes of uninhibited actions.

In psychology, psychodrama is a type of therapy that utilizes role-play to explore the inner world of an individual. It’s designed so that people can express themselves through spontaneous dramatic action and impulsive creativity. Video games are outlets for us to do just that in a controlled environment. In these single-player role-playing games, you don’t need to perform for anyone but yourself, so who you play can be a fun experiment where you act out the ideal person you want to be.

Personal opinions on personality

I find myself replaying a Telltale game after a couple of years, and to my surprise, I repeat the same choices and get the same ending. This may mean that there is a consistent sense of self that continues throughout time, but that doesn’t mean that I haven’t changed or grown as a person, just that, in this particular set of scenarios, given two or three alternatives to pick from, I would still choose the same ones as I’ve always chosen. There’s a comfort in that. Despite time and how different the world is, some things never change.

At the end of the day, what tests and statistics tell you matters less than how you feel when you get them, or the emotions that swell up when you play a game and are faced with the impact of your actions. These don’t lead to concrete answers of who you are, but an understanding that steps that much closer to self-discovery. Who you are is dependent on the context, in real life as much as in games, dependent on the parameters of where you live and when.

If you live in a walkable city with a tight community, you may be more social, and more encouraged to network. In a pandemic, you may spend more time alone and be more introverted. Instead of seeing people who play Call of Duty as inherently more neurotic, a better way of looking at things is that Call of Duty’s systems stir up competition and negative emotions, which makes people more neurotic than when they are playing Death Stranding. Maybe personalities are less immutable constants and more an indicator of who you are in a moment in time and place.