What Video Games Can Teach Us About Suicide

How Cyberpunk 2077 offers a glimpse into the aftermath of suicide

Why do we play video games? Is it to experience something unattainable in real life? Is it to escape? Why do we escape? Is it because something traps us? Is it because we have been put in an unbearable situation that hurts and pains us? Is that why some people choose death far earlier before they’re due? To experience something unattainable in real life? To escape?

Cyberpunk 2077 has relevant depictions of suicide that have yet to be explored in depth. Games as an entertainment medium, and this game, in particular, have a way of portraying serious real-world themes innocuously. Through controlling a character, there are certain experiences and points of view that could not be achieved by merely watching or reading about someone else’s life. Here, you, the player, are complicit. The conditions that lead to suicide and the protective buffers that prevent it are represented through simulation. By providing a certain level of control, the consequence is more visceral; failing to save someone or disappointing someone else virtually becomes near-reality.

![[bf]What Video Games Can Teach Us About Suicide](https://www.superjumpmagazine.com/content/images/size/w2000/2024/05/1_vwzl8y9NOqzDxrW_lLjQOg-1.png)

The Setting

The world of Cyberpunk 2077 is depressingly hopeless, yet not too far from our own. In some aspects, it is a terrifyingly conceivable near-future. Originally coined in the late 1980s, the connotations of cyberpunk as a genre are closer to our reality than ever before. The future that was imagined back then is almost here, for good or for ill. The original meaning of the term discusses the imbalance between low-life and high-tech (Sterling, 1986, pp. 2–4). In the world of Cyberpunk, futuristic facilities with high-end technology exist alongside impoverished slums. This contradiction calls attention to the subgenre’s similarity to a social Darwinian experiment, one where the fast-forward button keeps being pressed (Lin, 2022).

It is a version of our world if the current pace of progress keeps escalating; if economic and technological development never stops to think about equality, well-being, or humanitarian consequences. An exacerbated future of our present where the rich get excessively richer, possessing control over all capital and political power, while the downtrodden are left with scraps, to struggle and kill for survival.

In this world, corporations run amok, morality is thrown to the wayside, and the line between self and others is blurred. Monolithic corporate buildings tower over the streets and blot out the sun. A fatalistic state of affairs dictates entire lives, where people feel like they have to surrender to the whims of market needs and the bottom line. It is perhaps the furthest and most feared end of late-stage capitalism.

Mike Pondsmith, the creator of the board game that Cyberpunk 2077 is based on, states that in this world, “You’re not fighting for truth or freedom, you’re fighting for a place to live.” He based his source material partially on Blade Runner and the elements of noir that it’s obsessed with. In noir, clouds hang endlessly over the protagonist, their fate doomed from the start, buried in rain and smoke. In noir, plans are portents of failure, human relationships are fragile and fleeting, and society always seems to favor others, especially those at the top of the food chain.

In the game, people without cybernetic implants will die; they cannot compete in jobs or survive on the street. People are encouraged to sell their flesh and humanity in exchange for sterner stuff. They must merge with machines to have a chance at survival let alone strive in the world. It is this disparity that is faced in today’s world as well. People living on the edge of cities and villages in third-world countries, those who do not have access to technology and cannot afford it, will be left behind if the world’s constant obsession with progress keeps being pursued. In the game, there is even a flashback, arguably one of the inciting incidents of the story, set in 2023, which is our past as much as it is theirs.

All is not entirely bleak, however; there are lights other than neon shining between the shadows of skyscrapers. These lights come from worthwhile souls, people fighting the same fight, struggling to survive. These friends that you as the player get to know and keep company, that you help and help you in return, they’re the life in an increasingly lifeless world. In a time where someone’s well-being is never a priority, where profit margins are the main concern, these people show you that some do care and that there is still humanity left in the world.

The People

Having real “connections” with other human beings, beyond superficial interactions in cyberspace, beyond the purpose of progress or profit, sometimes feels like an aberration. When a society is filled with such self-abandonment and inescapable bad culture; when everyone is objectified and treated as a commodity, genuine affection becomes a luxury (Lin, 2022). Yet it is this simple act of rebellion that tightens the bonds between you and the people you meet.

In a world where it is unnatural to care for others without thinking of utility or pragmatism, the natural act of resistance is to be human and to have human connections, to prioritize each other and not the individual. That is how Cyberpunk’s protagonist and, by extension, the player, fights the merciless world. Your character boasts about machismo, self-sufficiency, and brandishing autonomy, but by the time the credits roll, it is the people you encounter in your common struggle that matter most. But as in all noirs, tragedy is fated to befall you, and not without resisting.

In one of the game’s side missions, an ex-cop named Barry retires to his apartment building after his friend’s death. Two police officers wait in front of his door, worried, because he won’t open up. Through some effort, you can help them and talk to Barry in his room. Later, you find out that Barry’s lost friend is a pet turtle, and that he is far more depressed than the officers first let on. You can then tell the officers about Barry’s turtle or keep the secret to yourself. But if you don’t take his condition seriously, and don’t give all the information to his worried ex-colleagues, Barry will take his own life. Afterward, the officers will only be able to grieve.

Yet if you care enough to follow through on Barry’s story, find out about his friend, and tell the officers about it, they would empathize. With the full context of Barry’s troubles, they’d apologize for being too hard on him and for not seeing his pain, and they would share their own problems in the force and leave room for Barry to share his. This mission teaches players that by simply listening, opening up, and giving room for other people to open up, lives can be saved. All it takes is one other person to prove someone’s darkest thoughts wrong, but they have to be taken seriously first, in a safe space built on trust. In the end, it’s other people who save Barry, the ones who care enough to be aware of his needs and check on him.

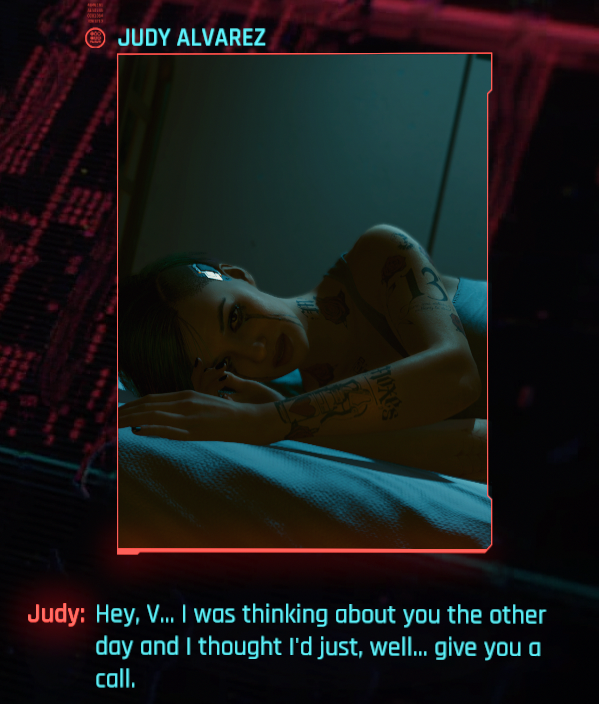

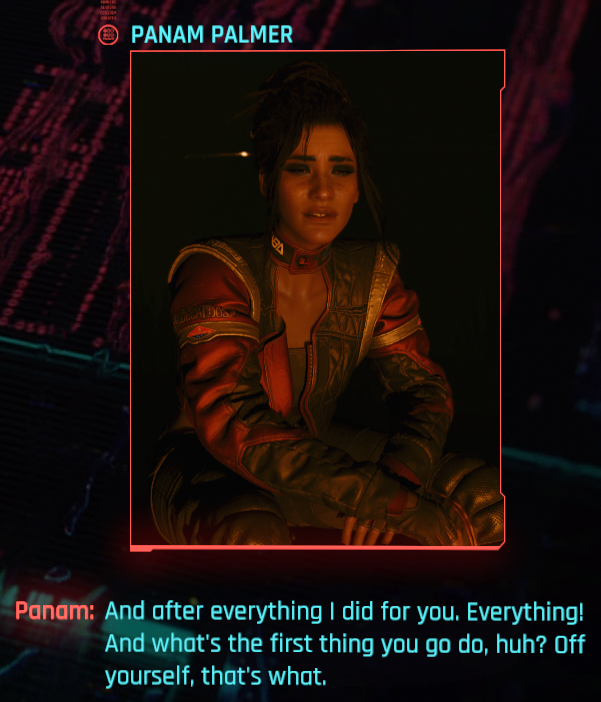

The loophole in the system, the way out of the oppressive environment of corporations, is human connections. Whether it be Panam, who the player meets from a nomad clan on the outskirts of the city, or Judy, who aids sex workers trying to make ends meet, you learn that corporations can kick you out with the drop of a hat, but people hold you together. People you can count on. Even the eponymous Johnny Silverhand, the terrorist/rock star played by Keanu Reeves, warms up to you by the end. His character acts as a misguided conscience, playing both the role of the angel and the devil on your shoulder. Trapped in your body, the game started with him trying to co-opt it and take it as his own, but he grows respect for you through your actions.

In the end, they can help you fight your struggle, but only if you trust them enough to do so. There is an ending where the player can choose to rely on the connections made along the way and fight back against the impossible together. But this is not about that ending. This is about the ending where the player chooses fear over friendship, choosing a misguided sense of self-sacrifice to lead them away. In this ending, you take the weight of the world into your own two hands and you crumble under it alone.

The Ending

In the book "Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism", writers Case and Deaton argued, “Rising economic and political power of corporations, and the declining economic and political power of workers, allows corporations to gain at the expense of ordinary people.” They consider that the rising number of suicides in the United States is largely due to the structure of its financial system. Furthermore, they compare the current world to a society of reverse Robin Hood, where resources are being taken from the poor for the rich. It is this dystopia that is causing existential despair for the majority.

This despair is a hallmark of the noir genre. Existential motifs in noir usually consist of a disoriented individual facing a world that they cannot escape. An existential choice is usually posed in stories where the “hero” must choose between two alternatives, the result of which will create either good or evil outcomes. But unlike other genres, noir protagonists rarely redeem themselves in the end. The fruits of their labor are never wholly good; there’s always a catch (Silver & Ursini, 2005).

In Cyberpunk 2077’s closing moments, the player is cornered, and forced to make a choice. You have to attack the largest corporation, Arasaka, that has a choke hold on the entire city. Either you bring your friend, Johnny’s friend, or someone from the inside to mount the assault, but every choice has its consequence. There is not one decision that solves all your problems. You can lose Johnny or you can lose control of your body to Johnny. There is no clean escape but death.

Yet maybe you should not have attempted escape. Maybe you could have borne the pain together. Noir is often synonymous with tragic endings, and here it’s no exception. The protagonist has an inescapable fate, a curse flung upon you beyond your fault, and it is carried for the rest of the game. So in one ending, thinking that every other choice would lead to more death, the player can choose to end the protagonist’s life. In this final fleeing act, everything built beforehand is given up, every hard-earned relationship and reputation. Thinking it’s the lesser of other evils, you choose the easiest escape, forgoing the well-being of all the people you’ve met. And in the credits, you are greeted by them, greeted by grief, in all its many shades.

In the more conventionally climactic endings, either you die or Johnny does. Either you remove his consciousness or he takes over your body. But if you choose to take your own life, everything ends. And in this death, Johnny can understand and respect your decision for some twistedly honorable reason. In Japan’s ancient samurai class, voluntarily choosing death was an act of individual freedom and self-determination, a view that the world has long outgrown.

Honor for the individual often forgets or willfully disregards the well-being of others, those left behind by the so-called honorable dead. Back then, finding the right time and place to die was deemed dutiful. However, beyond the mythic meaning or symbolism of plunging a blade into yourself, the actual act can also be seen as a sign of shame, desperation, panic, and protest (Pierre, 2015). And in Cyberpunk, a world where morality is already askew, fear and frantic despondency can easily be misconstrued as honor and bravery. By mistaking martyrdom for honor, you can forget to honor the wishes of everyone else.

Source: Author.

But while some can understand the decision, others are left with grief, confusion, and guilt over being powerless. Some can only answer in tears, leaving you, the deceased, a video message about how much they miss you. It's a message that an actual person could never witness in actual death, but is possible to observe in a simulated one, through the medium of video games. Perhaps most tragically, our closest connections feel an act of betrayal on our part and act out in rage, leaving a bitter taste in their memory. Those abandoned by the willingly deceased may feel rejected because they see the dead as choosing to give up and leave their loved ones behind. They are then left with the lingering question of why their relationship with the person was not enough to keep them from taking their lives, and worse, if it was ever their fault; if they had a part to play in the death (Young et al., 2012).

A common consensus for suicide loss survivors is that they perceive the death as a betrayal by the deceased or a failure from the bereaved. For many people, the choice of dying is perceived to carry a targeted message for the survivor about their relationship’s lack of worth. All of this can compound the bereaved’s already alienated and estranged feelings for the deceased (Jordan, 2020). As Sands (2009) in Jordan (2020) has pointed out, the survivors often need to “try on the shoes” of the deceased, and imagine the reason behind the act, but ultimately they must “take off the shoes” and live their lives.

And through Cyberpunk 2077, everyone can try on the shoes of someone who chooses death. Temporarily, they can play the part of someone who takes their own life before returning to reality with that experience intact. There is an impossible intimacy achieved through this ending in the game. As the credits roll and the names of the developers whizz by, the player is immersed in an almost out-of-body experience, being able to know what people think of the protagonist after their last breath.

Intentionally or not, this coda to the protagonist’s life, with specified messages from in-game friends, is analogous to how life still goes on for others, even when one is dead. This realization can be crucial for someone contemplating the act, to notice that escaping one’s station in life leaves behind a world of baggage for others to carry for the rest of their lives. As we see, if only we had kept going, even in the credits, there’s still music. This experience of being someone who takes their own life, understanding the alternatives and the choices that led to that point, yet also witnessing how other people feel being left behind, creates empathy, with the character attempting the deed, and also with the people who care for them.

The fact is, you can never know in your lifetime the consequences of your death; only in a virtual life can we even begin to imagine. The game encapsulates the terrible repercussions a death can wreak on your compatriots. A state of the world that devalues human lives can instil a myopic way of living, as if all other avenues are closed and the future will remain woefully the same. But it is other people who inspire worth. It is the relationships and chance of relationships with other people–the ones that leave a mark, if not in life, then in memory–that remind us that there is always something worth fighting for.

Like Keanu Reeves once said, what’s certain after death is only that “The ones who love us, will miss us.” Though sometimes things may seem hopeless or inescapable, though the world or the powers that be can seem to undermine us and our well-being, though we may feel like we live in a bleak noir with no happy ending, we are never alone. If we attempt premature escape before the curtain call, we’ll miss out on what awaits, in the next act, and what’s more, we’ll be missed in return.

If you or someone you know is in need of help, don’t hesitate to reach out. Whoever and wherever you are, you are not alone. It’s not the end of the world, there are people who care. You can visit Open Counseling for a list of International Hotlines. You can also find a helpline from the International Association for Suicide Prevention.

And for those of you who have lost people because they chose death, none of you are alone. Do not be afraid to seek help as well. You can visit Survivors of Bereavement by Suicide for support and information. You can also visit the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention for resources.

References

Jordan, J. R. (2020). Lessons Learned: Forty Years of Clinical Work With Suicide Loss Survivors. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00766

Lin, J. (2022). Viewing the Contradiction from Cyberpunk Under the Operation of Capitalism. Zhuhai College of Science and Technology.

Pierre, J. M. (2015). Culturally sanctioned suicide: Euthanasia, seppuku, and terrorist martyrdom. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.4

Silver, A., & Ursini, J. (2005). Film noir reader. Limelight Editions.

Sterling, B. (1986). Burning Chrome by William Gibson (pp. 2–4). Harper Collins.

Young, I. T., Iglewicz, A., Glorioso, D., Lanouette, N., Seay, K., Ilapakurti, M., & Zisook, S. (2012). Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Bereavement and Complicated Grief, 14(2), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2012.14.2/iyoung