What is Progress?

Exploring various interpretations and signs of "progress" in video games

The games industry in the late 1990s was in the midst of a technological arms race. The industry had been rapidly expanding for many years on the back of the Dotcom Boom, and the Internet was helping to proliferate gaming culture faster than ever before.

With the introduction of 3D accelerator cards, the arms race witnessed the emergence of its latest weapon. Specifically, PC games were transitioning from the pixelated 2D abstraction of sprites to the realm of three-dimensional models, bump-mapped textures, and real-time lighting, thanks to groundbreaking technologies like 3dfx Interactive’s Voodoo graphics cards. Likewise, the console market was leaving the sprites behind, with the Nintendo 64 and PlayStation both pushing the console market deeper into the 3D frontier.

Technological leaps forward were synonymous with progress in game design, while victory was decided by benchmarks and unit sales were the spoils of war. However, in the 2010s, the previously unmatched reign of high-quality AAA games was being eroded by the rise of a new era - low-quality indie games and remasters. What happened, and why?

The spectre of technology

More than any other art form, games have a deeply intrinsic relationship with the medium used to create them. A painting requires nothing more than a canvas and a type of paint. A book requires ink and paper, or in more recent eras, an e-reader and digital file. A film requires a screen and some method of projection. But games are complex, the result of commands sent to hardware, rendering processes, and translation of user inputs. They are often written in languages that are tied to a specific type of technology or platform. You cannot simply load a Nintendo game onto a PlayStation or a Mac computer. A game written for the IBM XT personal computer in the 1980s will not work on a modern Windows PC without a great deal of tinkering and emulation.

Other art forms, for the most part, do not suffer from the perishability of their medium. Paintings, sculptures, and books have existed for centuries and even millennia. Paper does not undergo “upgrades” that make previous types of paper obsolete and incompatible. Even with film, the ability to record and reproduce a film in a newer format offsets the obsolescence of older mediums.

Games do not have that luxury.

The technology we use to experience them is perpetually evolving and changing, and the rate of obsolescence vastly outstrips the best efforts of game preservationists. While preservation continues to be a challenge in all fields of art and history, the issue is most pronounced in the games industry.

Though technology has been the source of an immense challenge for game historians and preservationists, it has also been an enormous boon to game designers. The rapid advance of computing technology over the past 50 years has provided developers with an exponentially expanding toolset to communicate their ideas. Only 20 years after 1972’s Pong, Nintendo released Super Tennis on the Super Nintendo. Fifteen years after that, thousands of living rooms worldwide saw friends waving their Wii remotes back and forth while they played tennis in Nintendo’s Wii Sports. It’s hard to imagine that Allan Alcorn could have predicted what tennis games would look like a mere three decades later.

Pong (1972), Super Tennis (1991), and Wii Sports (2006). Source: Wikimedia Commons, Author, and StrategyWiki.

Marketing departments have exploited this relationship between games and technology from the beginning. A 1996 magazine advertisement for The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall stated:

"Daggerfall's world is twice the size of Great Britain, filled with people, adventures, and scenery as real as reality."

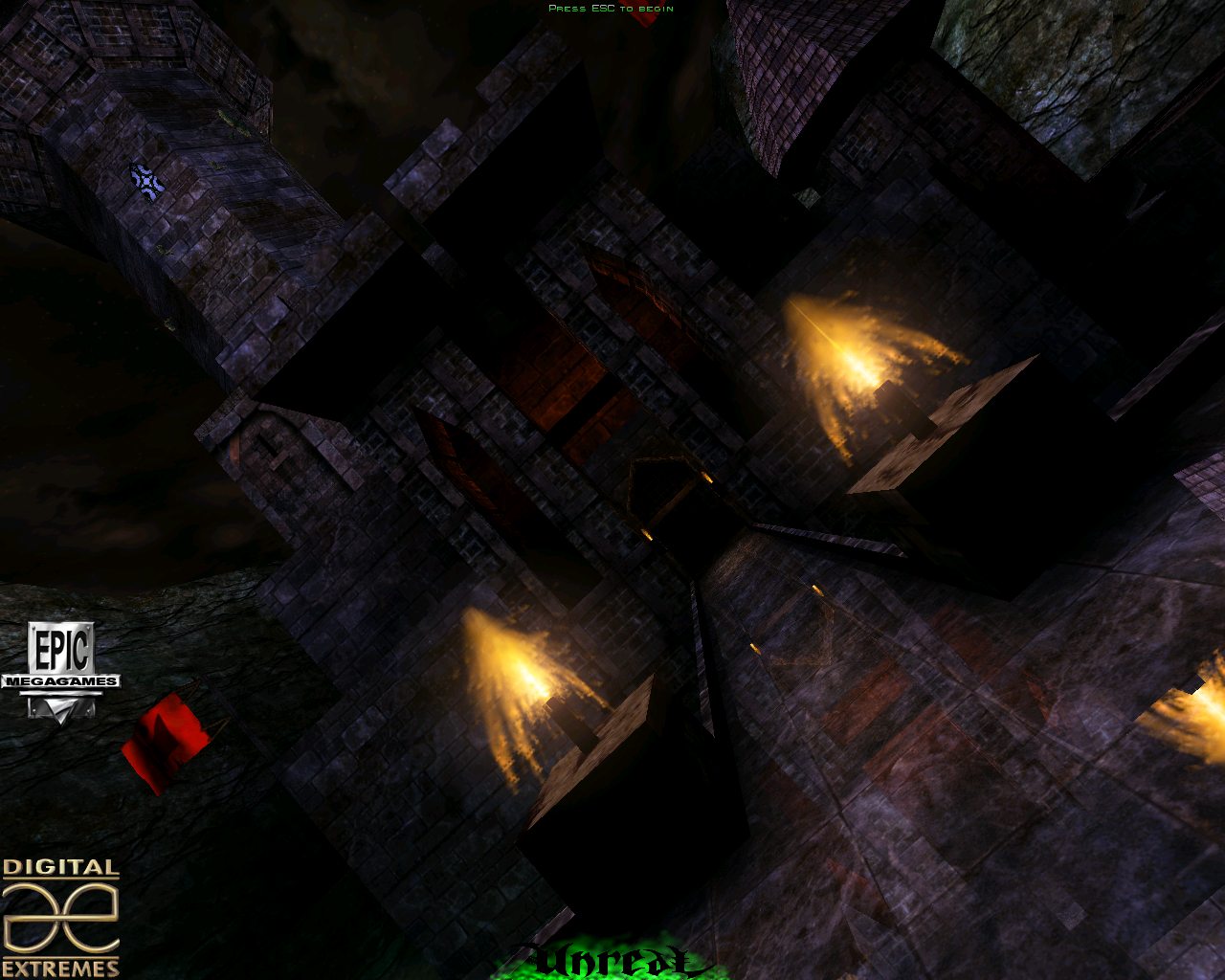

In 1998, Epic Games (then known as Epic MegaGames) released Unreal, featuring the debut of the now-ubiquitous Unreal Engine. It was a huge leap forward for FPS gaming, and a chief reason for its critical acclaim was Unreal’s spectacular visual fidelity. I can recall my own feelings upon first stepping outside the crashed prison ship and seeing that iconic scene of a waterfall plummeting into a deep canyon below. “Games will never look better than this,” I naively told myself.

Competitors in the console market rivalry between Microsoft’s upstart Xbox and Sony’s sophomore PlayStation 2 frequently drew battle lines based on technical performance. Gaming magazines often compared the two platforms on hardware specs and game performance, rather than assessing games purely on their design merits.

Games rely on creating memorable interactive experiences, and when the latest tech allows you to craft an immersive experience unlike any that has come before it, then it is no wonder that critical success often accompanies technical innovation. But, as the perceived leaps forward become smaller, the benefits of technical superiority become less apparent.

The visual communication plateau

Back in 1998, I thought games would never look better than Unreal, and I was wrong. I'm not stupid enough to make that statement again, but the graphical leaps forward of previous decades are today more commonly “measured steps”.

Back in 2018, EA's Battlefield V arguably heralded the dawn of the "Ray-Tracing Era", being one of the earliest major releases to natively support a technology that had by then become relatively attainable on consumer hardware. However, for many gamers, the increased visual fidelity that ray-tracing offered in those early years wasn't worth the extra cost in hardware. This was compounded by the cryptocurrency bubble and then a global semiconductor shortage that vastly inflated the price of even entry-level graphics cards. Even today, with ray tracing being more widely supported, the performance cost is arguably not worth it for many games, which will opt for higher frame rates over greater visual fidelity.

Games rely on creating memorable interactive experiences, and when the latest tech allows you to craft an immersive experience unlike any that has come before it, then it is no wonder that critical success often accompanies technical innovation.

The Ray-Tracing Era has exacerbated what has been occurring since the early 2000s: diminishing returns on pushing performance. In 1996, a 3dfx Voodoo card retailed for around USD $299 on launch (that's about USD $600 today when adjusted for inflation), and the Voodoo was simply the best consumer-grade graphics card on the market. Compare that to today's graphics card prices, and the difference in the value assessment becomes quite staggering (even when you factor in that Voodoo cards were not standalone, and needed to be paired with a standard "2D" VGA card). More to the point, though, is that the difference in visual fidelity was staggering. Seeing a game with a Voodoo for the first time was a transformative experience, but the difference between a top card like the Nvidia RTX 4090 and a budget card like the RTX 4060 is hardly earth-shattering. The fact is that, even on lower-end cards, games can still look great.

Before going on, I want to clarify one point — the difference between game performance and visual communication. Game performance — framerate, number of computations per second, physics calculations, etcetera — has continued to advance at an impressive rate. On the other hand, visual communication is the ability of a designer to communicate a concept through graphics, textures, and animations.

With raw processing power, computing power has a limit – the speed of an electron moving through matter. Computing continues to push those boundaries, but the cost-benefit analysis for games is different from that of computer engineering, and there is a point where it stops making much of a difference to visual communication. The latest hardware offers incredible leaps in performance, with the ability to emulate accurately the path of light rays on reflective surfaces, create interactive physics between objects, or upscale textures on the fly. However, the concepts that this additional hardware is able to communicate are limited. There is only so much extra detail you can add to something like an in-game car, a dog, or a building. The average gamer won’t necessarily care if powerful and expensive hardware accurately models and animates the individual strands of hair on a character’s head. All they care about is whether it looks like hair.

Military-themed FPS games at 10-year intervals: Wolfenstein 3D (1992, Top Left), Medal of Honor: Allied Assault (2002, Top Right), Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 (2012, Bottom Left) and Call of Duty: Modern Warfare II (2022, Bottom Right). Source: Author and Steam.

Back to basics

Since the dawn of the indie and remaster boom in the early 2010s, there has been a noticeable return to lower-fidelity graphics. The reasons for this are many; developers are banking on nostalgia, of course, and simple graphics require less development overhead. One might have initially argued that this was a fad, but 14 years later, I think it is safe to say that lo-fi games are here to stay.

I’d argue that one of the big reasons for the emergence of lo-fi games is the growing maturity of the games industry. The combination of the growth in indie/retro games and progress in graphics becoming more granular, with resources devoted to less obvious technical details has created an environment where audiences that consume games are assessing graphics in a more aesthetic frame of mind, rather than a technical one.

Perhaps another contributing factor is the increasingly uninspired state of AAA gaming. AAA developers have always focused on utilizing the latest technology, but despite their visually appealing nature, they have burnt much goodwill with excessive monetization, buggy releases, and bland gameplay.

The days of games being punished in reviews for not looking cutting-edge are, largely, a thing of the past. It still occurs, usually when a game advertises itself as groundbreaking when it’s not, but most of the time, criticism of graphics is more focused on artistic coherence rather than technical brilliance.

One of the great positive side effects of this change in perspective has been the reinterpretation of many classic games that were once criticised for their dated look. Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura was one of these titles; it looked dated before it was even released and was judged accordingly. But as many players who braved the game’s many bugs found at the time (and many have since), Arcanum is an RPG with incredible depth and a truly unique world.

When there is no need to maintain currency with the latest tech, critics evaluate a game based on different aspects, such as mechanics, story-telling, aesthetics, and gameplay. The mechanics might still feel dated, but this allows for a reasonable comparison between many classic games and their modern counterparts.

Boomer shooters: A case study

The release of David Szymanski's DUSK in 2018 was a defining moment in the emergence of what would come to be known as the "boomer shooter" genre. After a decade of iron sights, regenerating health, and grounded settings, shooter fans were ready to return to the genre's roots: gore-soaked, lighting-fast, run-and-gun tests of player skills and reflexes. DUSK showed that, far from being a tired genre, there was still life to be found in classic shooter design.

The years since have seen an explosion of interest in the genre. HROT, ULTRAKILL, Project Warlock, Proteus, Ashes 2063, Amid Evil, Cultic, and Selaco are just some of the titles that have received acclaim. A poster child for this classic shooter rebirth was Ion Fury (Voidpoint Interactive, 2019), a game developed in the Build Engine. If that name sounds familiar to those who have been around the block a few times, the Build Engine was used for many of the games that were the inspiration for this genre rebirth, titles from the pre-millennium FPS heyday like Blood, Shadow Warrior, PowerSlave and of course, the mighty Duke Nukem 3D. Seizing on the popularity of this FPS renaissance, developers like id Software, Apogee and Nightdive Studios released remasters and remakes of classics like Doom, Quake, Rise of the Triad, Turok, and many more.

1993's Doom vs. 1999's Quake III Arena. Source: Author.

The days of games being punished in reviews for not looking cutting-edge are, largely, a thing of the past.

If you consider DUSK to be the beginning, then the boomer shooter genre has now reached the same age as Doom was when Quake III Arena was released in 1999. By most metrics, the genre is doing better than ever, but from a technical perspective, there’s been little progress. Released in 2024 by Altered Orbit Studios, Selaco was developed using the GZ Doom engine, a source port of the original Doom engine from 1993. Yet, while the tech hasn’t advanced at all, the technique has taken leaps and bounds. Developers are constantly finding new and novel ways to employ tech that is in some cases almost 30 years old.

The big reason behind the longevity of the boomer shooter revival so far, and other retro-revival genres like classic RPGs, driving sims, and strategy games, is that these aging engines and graphical styles can communicate design intent effectively, without relying on performance-taxing techniques. Yes, Cyberpunk 2077, Elden Ring, and Forza Motorsport look spectacular, but clever indie developers have been showing for many years now that gameplay always trumps technical complexity, and an adept designer can deliver artistic impact in a dated style just as well as a designer using the latest technology.

If games are truly art, then the medium used to create them is not central to their worth. I highly doubt that Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) viewed the works of Rembrandt (1606-1669) with any less admiration or respect, simply because Rembrandt was using a medium and style that, in Picasso’s day, was no longer current. Similarly, many contemporary artists strive to recreate the style and technique of Baroque masters like Rembrandt in 2024

Likewise, a game released in 2014, or 1992, or 1979 is no less important today than it was at the time. These games are not “obsolete.” They are merely of their era. The revival of classic genres is a testament to this. The games industry has reached a level of maturity where classics are being reinterpreted as a defined style rather than simply being dismissed as obsolete.

The intrinsic relationship between games and technology will continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in game design, but it is design methodology and artistic interpretation that continue to broaden game design horizons. Progress is not framerates, clock speed, and polygon counts. It is the creative minds that drive the industry, perpetually reinterpreting their influences and breathing new life, innovation, and richness into the hobby.