What is Difficulty and Fairness in Video Games?

Examining two divisive topics in the discussion about gaming

If we compare a video game's challenge against an opponent (human or computer) to a race between two climbers to climb a mountain, the difficulty of the game would be comparable, first of all, to how high, steep and inhospitable the mountain is, and secondly, how skilled the competitor is. On the other hand, the fairness of the game would be comparable to the possibility that either of them can win and the parity of equipment and game information between the two climbing competitors.

Today I'm going to build on the idea behind this analogy to introduce what difficulty and fairness mean in game design. These concepts are complex and deserve separate treatments, so I intend to write more essays on these concepts. The current text is only introductory. Since the purpose of this text is to serve as an introduction to the subject, I will limit it to four topics:

- First, the distinction between difficulty and fairness, demonstrating how these concepts are independent;

- Second, the distinction between intellectual/mental difficulty and physical difficulty;

- Third, a topic demonstrating how difficulty and fairness are complementary (how these concepts can be combined in game design);

- Finally, a topic of balancing and vulnerability.

Difficulty and fairness

First things first. When we complain about some obstacle (boss, puzzle, etc) in a game that we can't win, it can be for one or both of these two reasons: it's a difficult obstacle or it's an unfair obstacle. Let's see what these things mean, and why they are different and independent.

Theoretically, the distinction between these concepts can be seen by the nature of each one of them. Difficulty is a pedagogical and labor concept; something is said to be difficult in terms of the effort and time it takes to get it done or learn about it. On the other hand, fairness is an ethical and legal concept. Competition is said to be fair, for example, in terms of making it possible for any one of its competitors to win, and not giving an unjustified advantage or disadvantage to any of the competitors.

Practically, the distinction between these concepts can be easily verified by counter-examples. I will show below two examples that show the independence between these concepts. Something difficult that is neither fair nor unfair; and something unfair that is not necessarily easy or difficult.

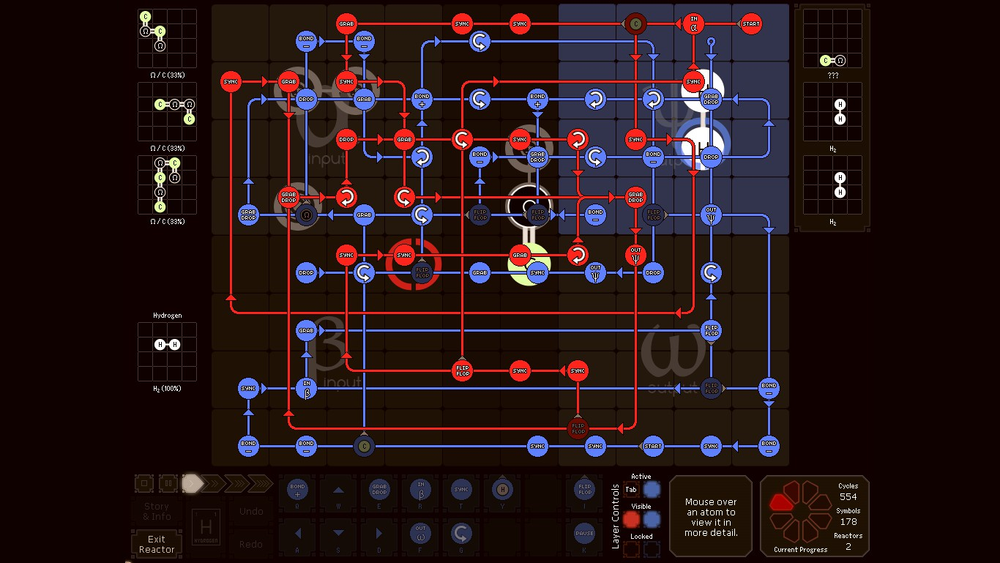

Consider any kind of puzzle in SpaceChem (2011), by Zach Barth, where you need to make the right connections to generate a chemical element. There is no time and no competitors, everything a player needs is given, he just needs to reason to solve the problem.

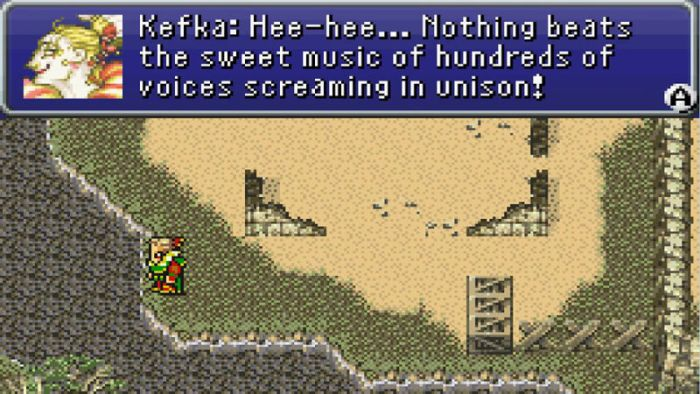

On the other hand, if in a game's story a cruel villain achieves his goal of world domination, we consider that unfair to the other characters. Note that this judgment has nothing to do directly with whether something is difficult or not; indeed, if that were so, perhaps we should consider how difficult it was for the villain to have achieved his goal. We have here two examples that show the independence between these concepts.

However, although the concepts of difficulty and fairness are independent, they are complementary, and this is what makes it possible to speak of fair difficulty and unfair difficulty in video games. But to understand how these hybrid concepts work, we first need to better understand how to apply difficulty and fairness to the video game experience.

Left: SpaceChem (2011), by Zachtronics Industries. Source: Wind Catcher Games.; Right: Kefka, Final Fantasy VI Advance (2006), by Square Enix. Source: Digitally Downloaded.

Physical difficulty and intellectual/mental difficulty

Here at SUPERJUMP, Josh Bycer, in Debating Difficulty in Video Games (2021), has already discussed in more detail the concept of difficulty, relating it to approachability. We can summarize the question of the difficulty in the gameplay experience in two factors:

- the complexity of gameplay (that is, the number of elements and functions assumed in the interactions); and

- the learning curve (learning design for the virtuous use of their systems).

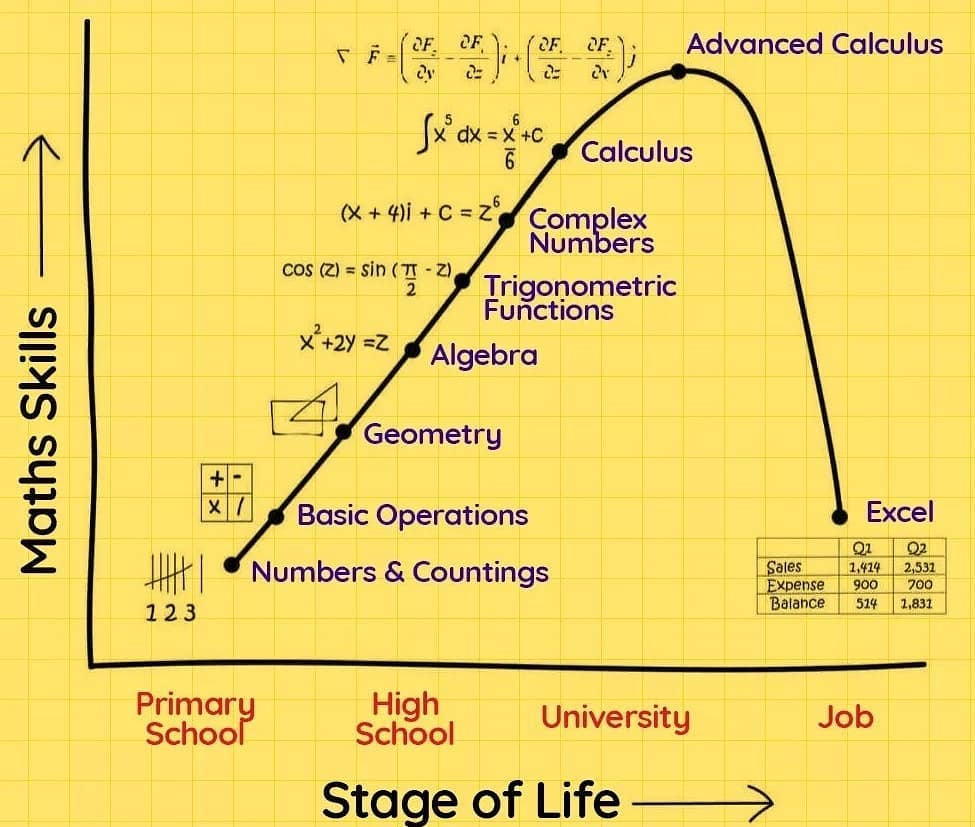

For anyone who wants to delve deeper into the concept of complexity, I recommend my essay The Difference Between Complexity and Depth in Video Games (2022). The concept of learning curve was illustrated to me with an image of the previous topic in relation to mathematics. Learning curve, in the context of gameplay, is a progressively more complex sequence of content and interactions necessary to overcome obstacles (enemies, problems, or the scenario itself), for example, a boss of Dark Souls.

As Chris Priestman analyzes very well in his essay Tomb Raider: The World Behind the Walls (2017), in Heterotopias oo1, difficulty is not always associated with enemies, but sometimes it can be in the scenario itself. This is the case with the classic Tomb Raider series whose first titles required millimeter-specific jumps. The difficulty here is not in the relationship between player and enemy, but between the player and the geometry of the level design.

Left: Dark Souls (2011), by From Software. Source: Boss Fight Database (YouTube) ; Right: Tomb Raider: Anniversary (2007), by Crystal Dynamics. Source: Facebook.

Note that the challenge of Tomb Raider, in this case, involves scenario observation and inductive reasoning, but the main difficulty factor is in action, more specifically in platforming action, in physical challenges that involve reaction time and hand-eye coordination. We call this kind of challenge physical difficulty. Note that there are physical challenges with or without enemies. And it is from the physical challenges that the genre of action in video games is defined, branching out into its various particular types (platformers, shooters, etc.).

In contrast to physical difficulty, there is intellectual/mental difficulty, games that focus on logical challenges (deductive, inductive, or abductive reasoning, as I showed in another article for SUPERJUMP, in 2021) are most often strategy or puzzle games, such as Into the Breach (2018), by Justin Ma and Matthew Davis; and A Monster's Expedition (2020), by Alan Hazelden. This type of difficulty is quite different from that, and I still intend to dedicate a specific essay to it.

Easy/Hard X Fair/Unfair

In Homo Ludens (1938), Johan Huizinga noted that there are two possible functions of a game: "dispute something" or "represent something". A game that is almost exclusively representational, such as a visual novel, is neither fair nor unfair, it is simply a question that does not arise for this type of game. On the other hand, when it comes to a game that involves a dispute (between players and/or computers), then there is naturally a concern to make this dispute fair between those involved.

As I mentioned in the first topic, we can judge as fair or unfair other parts of a game besides its gameplay, such as when a villain manages to take over the world. However, if we want to apply fairness to the gameplay, we first need to keep in mind that this presupposes that the game involves the "dispute something" concept. With this premise satisfied, we can ask ourselves what a dispute must have to be considered fair.

Fairness is something widely debated in ethics, legal theory, and political philosophy by authors such as Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, John Rawls, and several others. However, when this term is applied to video games, broader meaning of the term is aimed at, for example, the way Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics approaches it, summarizing it to:

"equally treat those who are equal and unequally those who are in unequal conditions."

Thus, considering a broad sense of fairness and the basic conditions for a dispute, we can infer two conditions for a gameplay experience to be fair:

- Tranparency principle: (i) all obstacles faced by competitors (real players or computers) must be identifiable by them; and (ii) all game rules must be available to competitors.

- Parity principle: (i) the game must give equal conditions to competitors with equal ability and numbers; and (ii) the game gives unequal regulatory conditions to competitors with disproportionate ability or numerical disadvantage.

The first principle (transparency) guarantees that the player will not encounter obstacles that are impossible to face, obstacles that are completely hidden and which he could only avoid with luck. A classic example of this is the famous use of Hidden Blocks in the Super Mario Bros. series as unexpected traps, and especially on fan-made levels in the Super Mario Maker subseries. And the second principle (parity) ensures that a dispute is balanced. An unbalanced battle tends to be frustrating for the loser and tedious for the winner. An easy example of this is using a much stronger character in a fighting competition.

Left: Super Mario Maker 2 (2019), by Nintendo. Source: Sankaku Complex ; Super Gogeta vs. Kid Gohan in Dragon Ball Z: Budokai Tenkaichi 3, by Spike. Source: PlayStation Blast.

It should be noted that the combination of these two parameters (difficulty and fairness) can generate different types of games, not only fair/unfair hard games but also fair/unfair easy games:

- hard fair

- hard unfair

- easy fair

- easy unfair

At the opposite extreme of fair hard gameplay, unfair easy gameplay is one that allows you to identify important things that your opponent can't (like taking advantage of a bug) or that allows you to be inordinately resistant or invulnerable to your actions, even disregarding the narrative context of the game. Good examples of unfair easy gameplay are those of games that provide an "invincible mode", as in Chrono Cross remaster (1999/2022), directed by Masato Kato.

And at the opposite extreme of unfair hard gameplay, fair easy gameplay is one where, while it's easy for one player, there's a contextual justification for it; the opponent isn't at a disadvantage by chance. However, even in these cases, game designers should use this feature with care, as it can lead to a tedious experience. An example of just easy temporary gameplay is at the beginning of God of War II (2007), directed by David Jaffe, where the player has very unbalanced power. But this is justified by how strong he's become since God of War (2005), also directed by David Jaffe, and it's also something used so that the player later feels the impact of losing his powers.

Left: Chrono Cross: The Radical Dreamers Edition (2022), by Square Enix. Source: Nintendo Boy. ; Right: God of War II (2007), by Santa Monica Studio. Source: Gamehag.

Balancing and vulnerability

Finally, let's address a problem inherent to many games (including board games): how to deal with differently (less and more) skilled competitors in a fair game? There are two classic solutions to this: selecting competitors (real players or computers) of similar skill level; or the handicap method. Both methods are efficient, but which one is better depends on the game proposal and the number of competitors.

In the case of a board game, chess is a good example of a game in which competitors play with others of the same level, with a rigorous system to establish the ranking among the players. On the other hand, there are board games that are as complex or more complex, such as shoji (a kind of Japanese chess) and goo, which work with a handicap system, giving a disadvantage to the most skilled player. In video games, both methods are widely used, but the handicap method is more common, particularly in video games with a choice of difficulty.

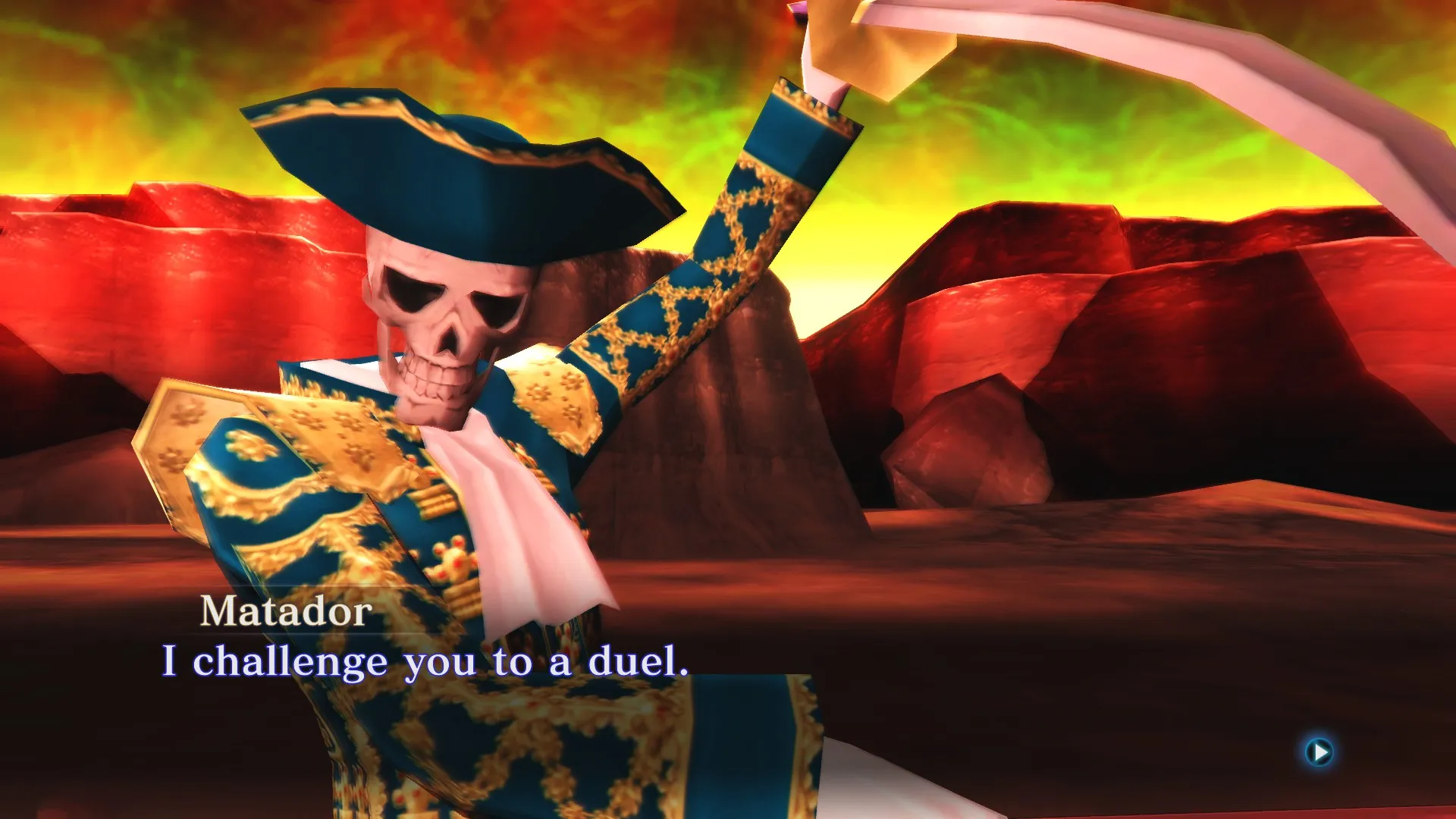

A video game does not necessarily have to be "fair", because, as we have already commented, quoting Huizinga's book, a video game can be not only competitive but also representational. In some cases, as in the Shin Megami Tensei and Dark Souls series, there is a clear proposal to place the player in a situation of vulnerability, so that he has a coherent experience in relation to a hostile, cruel, and treacherous world.

However, if you want to provide fair play in your game, it is worth considering the principles of transparency and parity. This applies not only to disputes between players but also between players and the computer/machine. What would be the fun of a computer beating a human at chess if the computer could have advantages above the rules of the game? That would be an unfair victory, and it is following this principle that competitions are made between computers and players.

In table tennis, for example, it has not yet been possible to create a machine that beats a human being by obeying all the rules of the game. If the machine could break the rules, it might have multiple arms, but that would just be an unfair victory. Jonathan Blow — director of Braid (2008) and The Witness (2016) — once talked in 2008 about the importance of having clear rules for a game. He highlighted the importance of this to give coherence to narrative design, as I discussed in another essay, The Poetics of Narrative Design in Video Games (2021), but, in addition, it is also fundamental to have an internal sense of fairness.

Left: Shin Megami Tensei III HD Remaster (2020–2021), by Atlus. Source: steamsplay.

Final considerations

In this essay, we introduce the difference between intellectual/mental difficulty (in strategy and puzzle games) and physical difficulty (in action games). Furthermore, we have seen how "difficulty" and "fairness" designate completely different things at first. However, they can be combined, in some cases, to generate hybrid experiences. In gameplay, for example, we can have easy fair, easy unfair, hard fair and hard unfair gameplay experiences. I have limited myself to a few examples due to the introductory nature of this text.

Finally, I discussed a little about balancing and vulnerability, which are fascinating topics that are related to the concept of difficulty, in general, and also to the second criterion of fairness (parity principle). I hope I gave the correct impression that an "unfair game" is not necessarily bad. Some games have moments of unfair difficult gameplay or unfair easy gameplay for good reasons, to represent oppression, among other feelings.

As I said at the beginning of this piece, I still intend to write other texts about these concepts, especially I intend to write soon about balancing intellectual/mental difficulty and about well-justified cases of unfair gameplay. So, if you liked this piece, I look forward to seeing you in future publications.