What Is A Plague Tale: Requiem Saying With Its Loading Screens?

It's not just bright lights

It’s a bit of a bummer that I’m about to spend this entire story critically justifying something I absolutely cannot stand. But justify it I must because I am fascinated by the way in which A Plague Tale: Requiem (from here on out, Requiem) takes something as terrible, invasive, and just plain-old cringe as the white loading screen and makes it a meaningful narrative and interactive device.

Like so very many before me, I am firmly in the “dislike” category when it comes to bright, whiteout loading screens in games.

It seems so straightforward, so elementary in my brain; games are often experienced in dark environments similar to how we view movies, in part to limit distractions from elsewhere in the room but also to reduce glare and allow for players to see details within shadows on their screens.

If all the above is true, then why do some developers insist on roasting my retinas by transitioning from a scene in a dark cave to an all-white loading screen? The contrast is so strong that my pupils can’t dilate fast enough. It actually hurts. How do these things pass QA testing?

Fromsoftware’s Elden Ring famously patched their white Bandai Namco “flashbang” loading screen out due to player feedback, and it was one of 2024’s biggest net-gains for all of humanity.

But something tells me the developers of Requiem – Asobo Studio – would (kindly and gently) slap me across the face if I told them to remove their white loading screens. Theirs, you see, are loaded with purpose – and it’s not so easy to wave away as just art direction and stylistic choice.

As loathe as I am to admit it, Requiem introduces narrative justification for their squint-inducing screens.

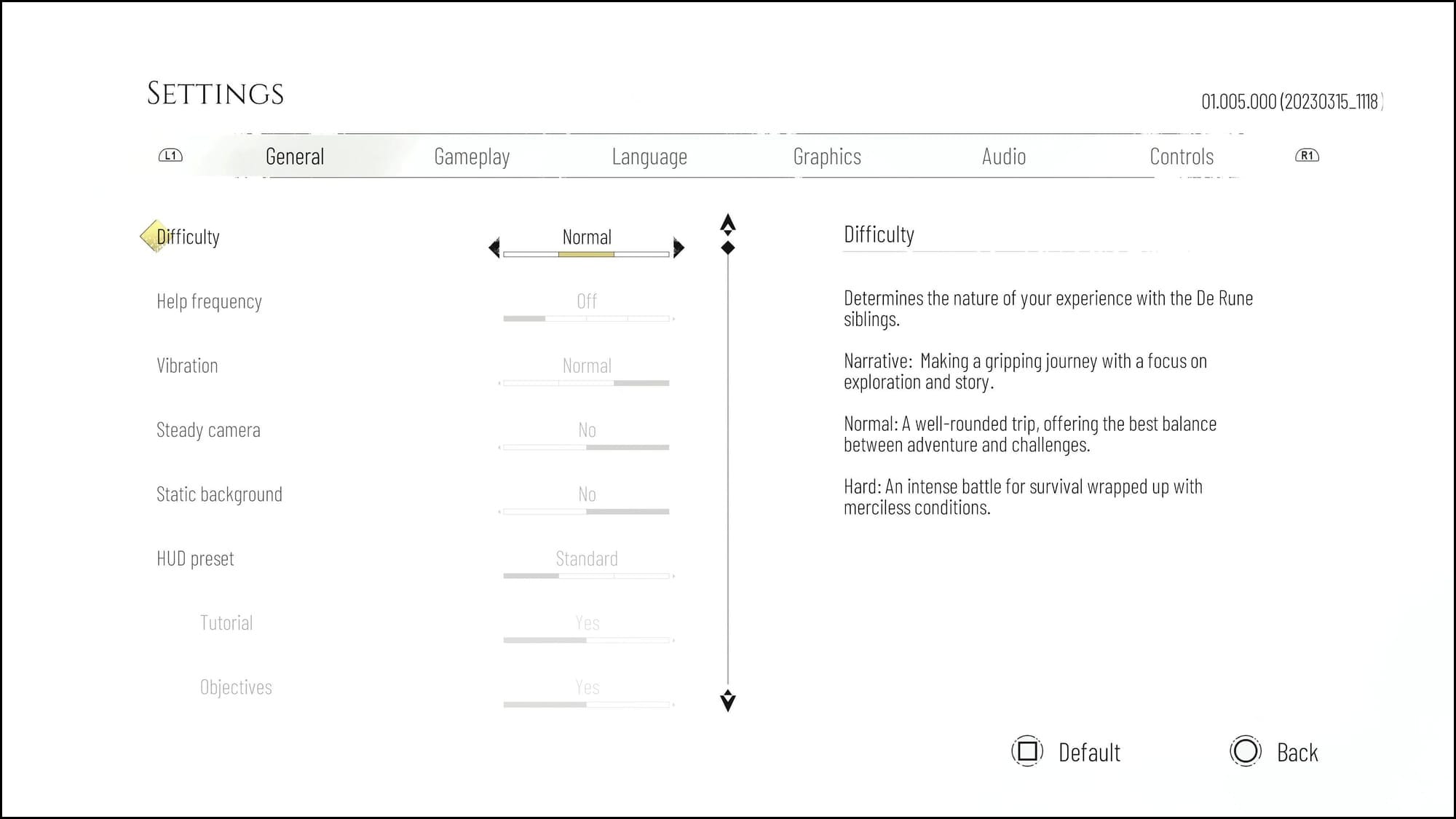

The game’s title screen and chapter transition loading screens bring about an intense, blinding light that really stands in stark contrast to the moody, shadowy, low-visibility corners of much of the campaign.

When they immediately follow those dark instances, the white screens jump out at you like a rat in the night – some sort of otherworldly punishment for an accumulation of unknowable transgressions. In what you think is a quiet, safe moment, these screens jolt you to full attention, eliciting a physical response – often a tangible flinch, an uneasy wince, or a repulsed recoil.

They make you uncomfortable.

And I can’t help but notice how harmonized that is with Requiem’s main cast and campaign. The second installment in the Plague Tale series spares no generosities to Amicia, Hugo, et al – the crew can’t count on two hands how many times they’ve fallen through a rickety wooden bridge, waded through murky, bloody waters infested with corpses, or flinched in disgust at a bursting womb of mucus-covered rats. That goes without mentioning Amicia and Lucas’ navigating rotting butcher’s runoff, or the few times she and Hugo are forced to push along or ride upon cages filled to the brim with decomposing flesh.

The things that Requiem’s cast are forced through during the game’s story are brutal, appalling, and gross. If a loading screen can make you wince in discomfort from the comfort of your real-life chair, then maybe you could make the argument those overly bright transitions are being put to some use – causing the player to physically react in a way similar to how they would if they were experiencing the game’s narrative in reality.

But we can go deeper than that. Maybe these loading screens mimic both mechanical and narrative devices in Requiem as well.

These white screens are so overbearing because it’s a lot of light, all at once. But shouldn’t that be a good thing?

In the moment-to-moment gameplay of Requiem and the entire Plague Tale series, you are nigh-addicted to light. You cling to its every flicker, dashing, leaping, and puzzle-solving your way from one well-lit haven to another. It is your lifeblood, your shield, your protector. You cannot succeed without it. We pull back and squeeze our eyelids shut in discomfort at these screens, but they’re really our safety net, loudly reminding us of their importance.

That garish brightness is not their only importance. These loading screens are bright, yes, but they’re also white and that might be an important distinction, yet.

In the moment-to-moment narrative of Requiem, Amicia and Hugo are on a quest for purity. Both fight tooth and nail to alleviate Hugo from the clutches of the Macula. From day one, the game’s story zeroes in on finding the young boy a cure - on purifying him of his ailment. And what's the color we so often associate with purity?

Is it possible to read the powerfully whitewashed loading screens as a physical reminder of the power of light in the gameplay mechanics and/or as the sanctity of the pursuit of purity in the game’s narrative? Can we interpret these moments as a reinforcement of Requiem’s themes, urging us to resist the darkness in our own lives and fight for purity against the odds?

Or, like the late-game chapters of Requiem itself, can we go deeper, still?

In the Plague Tale series, medicinal and combat concoctions are colloquially referred to as “alchemy.” On the surface, it reads like a bit of historically accurate flavor text to explain how Amicia is able to craft explosives with her bare hands in mere moments.

But what if I told you the entire series is an alchemical allegory, with the Macula carrying out the endgame of hermetic alchemy alongside Hugo, while Amicia undergoes a Carl Jungian-styled alchemical purification of the self?

As much as I wish I could, I cannot claim this ingenious, well-evidenced reading of the game as my own. That right alone belongs to YouTuber Lord JLO, whose detailed interpretation of Requiem gave me the final piece of the puzzle I needed to make this article a reality.

Lord JLO points out that in the first game in the series, A Plague Tale: Innocence, the title and loading screens are black, much like the first stage of the alchemical process – Negredo. In alchemical terms, Negredo is the breaking down of a material to its most basic parts, or in Jungian terms, the self-examination of a person, unearthing their inner shadow and ego. This phase of the process is represented by the color black in all alchemical texts and iconography.

In Innocence, Amicia’s untenable desire to protect her brother reveals a ferocious, angry, murderous side of herself. The constant tribulations of Innocence force Amicia to recognize and reckon with the darkest parts of who she really is.

Once Amicia has completed Negredo, she moves to Alchemy’s second stage: Albedo. This is the purification stage in which a material’s impurities are removed, or when a person’s ego and excess baggage are removed from the psyche. This is what is happening in Requiem, and as you might guess, this stage of purity is characterized by the color white – the same color as the game's loading screens.

In Requiem, Amicia is in constant conflict with herself, as she rebukes both Hugo and Sophia for chastising her about killing guards. There are multiple stealth encounters where Amicia counts her kills, sometimes with regret, sometimes like it’s just a game. Throughout the narrative, she grapples to justify her actions as done in defense of Hugo rather than interpret them as reflections of her character.

In the game’s final confrontation with the Macula, Hugo forces Amicia to unlearn these parts of herself. In the nightmare state of the Nebula, Amicia must run in the opposite direction that the phoenix statues point her in – symbolic of how she must realize the futility of searching for a cure for Hugo. Next, she must extinguish the fire fueling her battle against rats, symbolic of how she must admit her violence is unnecessary.

Throughout these moments, the screen burns yellow and orange, as Amicia transitions out of Albedo towards the third alchemical stage, Citrinitas – a yellowing stage embodied by the wisdom accumulated after the confrontation of the self.

That breakneck description is obviously a severe oversimplification of alchemy, Jung, and Plague Tale’s usage of those inspirations, but should hopefully serve its purpose here and keep my word count manageable. If you're looking for Rubedo – the final stage of alchemy – then look no further than Hugo and the Macula, haloed by a red sky and fusing to become complete in the game's final scenes. But that's a story for an entirely different article.

As you can imagine, there’s so much more to discuss (one hour and twenty-five minutes worth, to be exact) about how the Plague Tale series weaves alchemy within its framework, but I will leave that to your own curiosity, coupled with my strong recommendation for the video linked above.

What’s important to note for our purposes is this: if Amicia is experiencing the Jungian alchemical process throughout the Plague Tale series, then Requiem is largely her experience with Albedo, her own mental and metaphysical purification.

Asobo Studio uses its title cards and loading screens to hint at this transfusion.

Now, as we conclude, we have examined Requiem’s deeply symbolic, mechanically and thematically accurate bright white loading screens.

Yeah, they’re a little annoying, but they’re far deeper and richer than I could’ve ever expected. Hell, there’s more in these screens alone than some entire full-length games I’ve played in the past.

Whether they are generating a raw, real-life reaction, symbolizing the game’s themes, or representing the underlying inspirational works of the entire series, Requiem’s blinding lights are at least there for a reason.

Don’t give them too much grief until you know their whole story.