What Everyone Missed About Firewatch

The lack of choice is a feature

Did you play Firewatch? It had a pretty sexy marketing campaign back in 2015 and 2016, attractive enough to make certain reviewers decry it as the video game equivalent of Oscar-bait. I suppose that might be the case if we were to take the Academy at their word and accept that they award Oscars for outstanding technical or artistic merit. As it stands, the Academy award Oscars for ‘Outstanding Marketing Merit’ in the category of ‘Subject Matter Interesting to White Men.’ Video games, meanwhile, find praise for their consumer value per dollar, if at all. Firewatch earned tepid praise from the pretentious and buyer’s remorse from the disengaged players of games with more guns.

I find Firewatch interesting because a majority of players have shared they enjoyed the game for its artistic value and atmosphere but found themselves frustrated with the ending, the game’s world unresponsiveness, and the elements of player choice unrewarding. It was then that I understood why we’re having such trouble viewing games as art.

In most cases, we do not perceive the whole art piece, having started from the assumption that our form and manner of engagement with it are meaningless and aesthetically or narratively pointless. We don’t consciously register many of the mechanisms by which games convey meaning and narrative, and so we assume they’re not even trying.

This is similar to the way that someone analyzing Mark Rothko’s paintings will understand them much better, having visited, or even heard of, the Rothko Chapel. Art that explores the boundaries of a medium is often hard to parse without stepping back to examine everything about the experience — the framing or presentation of it, the title of the piece, the structure of the text in literature, the casting or marketing in theater or film.

These meta-textual elements do not enhance our interpretation when we’re trying to do a ‘death-of-the-author’ style dissection of the art as presented, but when we’re deciding what art to consume and buy in our daily lives, we’re mostly not analyzing it that way. We don’t buy things based on some objective standard of artistic merit, we buy them because something about that meta-experience catches our attention (i.e., the color of the packaging, the person selling it, the item’s immediate utility and price, the novelty or popularity of it).

In making purchasing decisions, the meta elements of art are often more impactful than the artistic elements of it. This only becomes more true when we’re talking about a medium that requires more from the audience to engage with it than any other medium to date. We’re still debating which kinds of interactivity count as “gameplay,” but if we can set that aside for a moment, we can perceive that the meta-elements of any art determine how we engage with it in a way that deeply affects whether we’ll enjoy it.

Remember Pan’s Labyrinth? Remember the marketing campaign that made Guillermo del Toro’s very adult, traditional (in the Grimm sense) fairy tale seem like an ethereal kids’ fantasy movie? Only for thousands of moms and five-year-olds to flee the theater twenty minutes in when a man dies of a graphic broken-bottle face-stabbing? Yeah, that’s what I’m talking about.

People who wanted Guillermo del Toro’s brand of grotesque beauty didn’t see it in the marketing and might have missed the movie. People who wanted the movie sold by the trailers were outraged and horrified. I’m willing to bet a lot of both would have been fine with the experience as presented, and willing to look for the artistic value in it, had it conformed somewhat to what they thought they were signing up for. Same as someone who likes horror novels will scoff at the happy endings in your adventure stories, someone who likes Michelangelo might have trouble seeing the artistic value in Rothko. That’s not because the value isn’t there, it’s because it’s not the art they understand and enjoy, so they’re not receiving the band of data on which it’s trying to communicate.

Engaging with games is always going to be a higher barrier to entry, just because if you don’t play a lot of games, many of the basic mechanical assumptions, systems, and shorthands that games use to onboard the player and convey subtext will be totally opaque to you. A non-gamer would take Firewatch as presented, learn WASD movement there in Henry’s shoes, and absorb the game’s narrative from the overt text and on-screen events.

That person wouldn’t become disappointed that the wilderness lacked a gratuitous amount of collectibles to find, because they’ve never played an open-world RPG. They might become disappointed with the narrative, find the stakes too low, and the story threads too unemotional and unresolved, because they didn’t register things the game was communicating through its mechanics. That person, overall, would probably conclude that the game is beautiful, well-written, and falls flat at the end. Based on a scan of the game’s reviews on Metacritic, this is the bottom of a shallow inverted bell curve, the least common opinion among a mass of extreme reactions.

The extreme reactions come in one of two flavors: the negative, of which there are many, and the positive, of which there is a handful. These, too, are all very similar to one another — they make the same points, cite the same events, and complain about the same things. The one thing every review, good and bad, seems to agree on is that the ending to Firewatch is a disappointment that resolves none of the plot points it spun out or offers any change in outcome based on the player’s choices. Consumers and reviewers share this opinion, those who hated the game, and those who loved it. Almost all the public response to Firewatch misses the point of Firewatch, because they’re not perceiving how the game is talking to them, and so they assume it has nothing to say.

Here’s where I break down the game and show you what I mean. Spoilers ahead, but if you’re worried about that with this game, then you’re already approaching the game in the wrong way.

We start the game with a story in text form, a story that lets us choose a few irrelevant details — the name of your dog, what you do on a date, that sort of thing — interspersed with our main character, Henry, making his way up to a fire watch tower in the woods of Wyoming. This intro is where people felt emotional dissonance because this text is actually what the game is about, but none of the things you do in the game relate to it at all.

A lot of games actually pull something like this, the Dark Souls series being a great example. Most Dark Souls fans will admit with a laugh that they have no idea what the games are really about. The lore is mostly in item descriptions and throwaway dialogue lines, almost buried. It’s also that the overarching plot of the setting and the series, the point of everything you actually accomplish in the games, is completely unrelated to the plots of the characters and enemies you’ll meet. Each individual character and event matters mostly as a symbol or representation of a theme. This creates ludonarrative dissonance, a case where the game’s theme or story doesn’t feel like it fits with the mechanics you’re using or the actions you’re asked to take.

It’s unfortunate that ludonarrative dissonance is such a buzzword now, because I think that makes people perceive it as an unmitigated flaw, something to be avoided at all costs, when in fact that dissonance is one of the tools games have to communicate with us. In the same way that an author might construct a sentence oddly, just to make us slow down and really think about the text as we read, or a cinematographer might overexpose a shot to give a scene a chaotic, overwhelming mood, an artist will often create this kind of intentional dissonance between elements of their art to call attention to something or provoke a particular emotional response. Firewatch does this almost constantly.

The plot of the game involves you discovering a mysterious person in the woods, chasing down suspicious signals and messages, and growing increasingly paranoid about a government conspiracy. These are all ideas any gamer would be well-versed in and ready to sink their teeth into. None of these things give you a full mouthful to chew on, though. They don’t matter, and also, they’re boring. Students studying deer mostly planted the signals in the woods. The person watching you is a nobody, someone more afraid of you than dangerous to you. Not a single plot thread goes totally unresolved, but the resolutions aren’t satisfying or exciting. This is because the plot is a distraction — what the game is doing with its hands while it’s talking to you. The mechanics, and lack thereof, are the actual text here.

You strike up a relationship with Delilah, your supervisor, via the radio. As the only real human contact the game offers, it’s understandable that players fixated on this relationship and attempted to “progress” it in the same way most games would permit: a series of dialogue choices ending in a vigorous session of pants-on snuggling set to swelling strings. It disappointed these players that they didn’t get to meet up with Delilah at the end, seeing the game as a choice between Delilah and Julia, Henry’s absent wife.

Impersonal Tragedy

Julia has early-onset dementia, and that is the underlying theme I think most people are missing when they look at the game: the internal conflict of caring for someone you love after an impersonal tragedy takes all the joy of their company from you. The game only asks one meaningful question, and it’s right at the beginning: “Will Henry go back to his relationship with Julia?” The ending doesn’t give you an unequivocal answer, not because there isn’t one in the game, but because your actions and behavior as Henry in this situation should have told you who your Henry is and what he wants to do now.

If you don’t know by the end of the game if Henry will go back to Julia or not...try to think about how you played it.

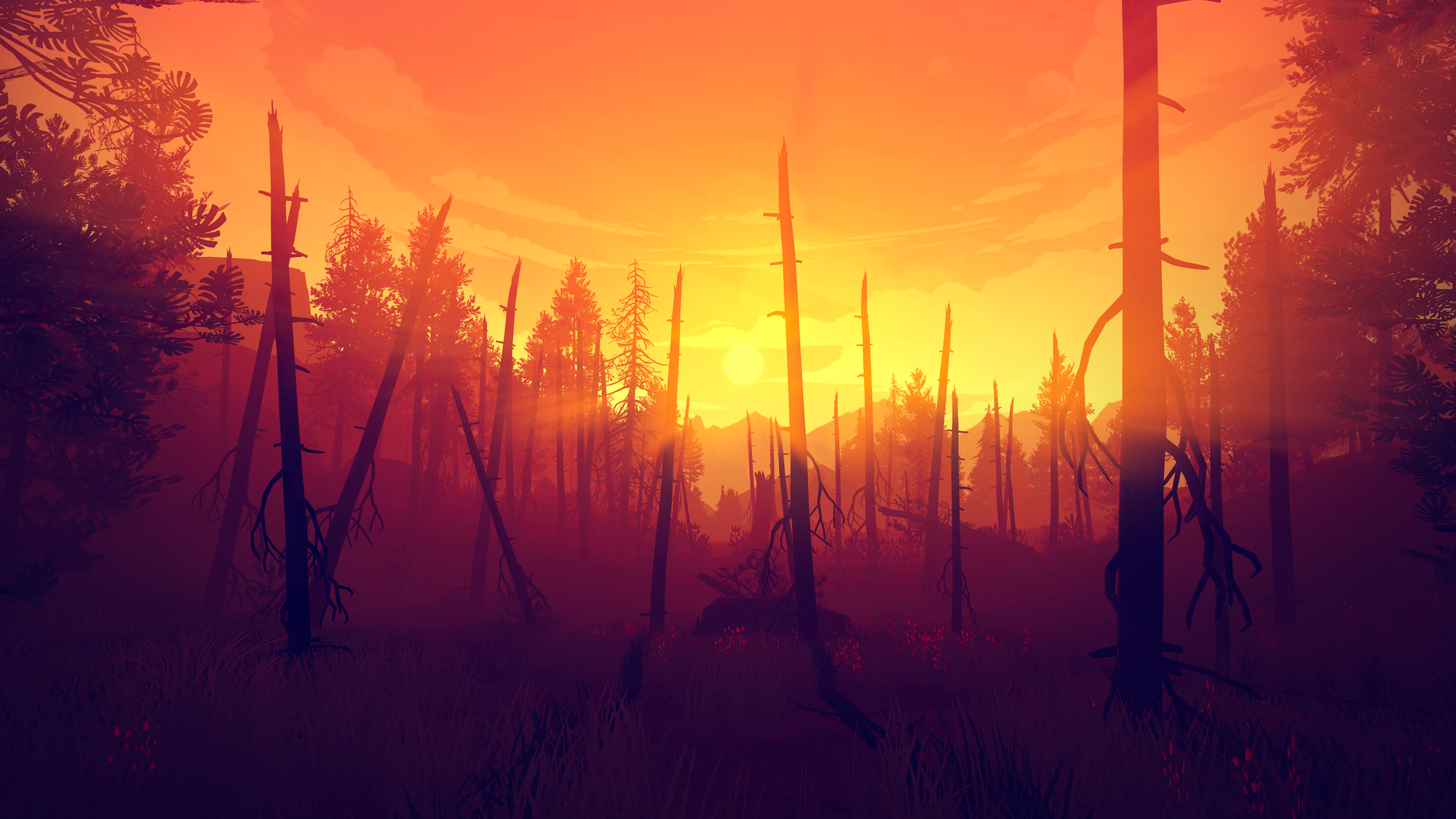

This is the theme of Firewatch - the commitment and selflessness required to look after something that cannot reward you for all the energy you put in. The theme is there in the environment's sparseness and its fidelity to the landscapes it’s representing, in the murderous banality of the traps in which they catch each of the main characters.

This job Henry’s taken, the job of fire watch or forest ranger is not a rewarding job. It’s lonely, isolating, it doesn’t pay especially well, and when it’s not dangerous, it’s dangerously boring. You do this job for one of two reasons: you value the land you’re looking after or you value the isolation it provides. The two other prominent characters in the story, Delilah and Ned Goodwin represent these positions.

Ned is the creeper in the woods, but he’s not really dangerous. He’s a man who went out camping with his kid, and when his kid was accidentally killed rock climbing, was too afraid of the potential consequences to return to society. Ned has been living in the woods for years and represents the escapist option here, the result of a chain of decisions that started with abandoning a person he loved when they were innocently and irrevocably hurt.

This is similar to what Henry has done to Julia. Henry is shown an image of himself, the rotting of the self that results when we turn away in fear from our life, willing to give up on human experience entirely just to avoid confronting our mistakes, willing to lose ourselves to our inhumanity if it means we never have to look in a mirror again. Or, ah — what was that, oh Tiny Samuel Johnson who lives on my shoulder?

"He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man."

- Dr. Samuel Johnson

Delilah did it too. She tells Henry in one of their conversations that her boyfriend ended their relationship during a period of profound grief after a relative’s death. She abandoned him to take this job and to make the break complete. A tragedy unrelated to either of them hurt her partner, and when it made her partner unable to give her anything back, she quit.

The ludonarrative dissonance is part of this theme. The indifference of the wilderness and the transitory and pointless involvement of random elements (such as the teen girls drinking at the lake who leave their beer cans scattered around or the station in the woods) all form part of the game’s thesis. Environmental pressures with no inherent meaning or perspective provide a looming threat via forest fire or falling rocks. This represents the meaningless cruelty of life, pain that no one sent, that teaches you nothing because it’s not about you, it’s just happening to you. That’s something gamers, unlike readers or cinemaphiles, are very unused to experiencing: a story that is happening to them, but not about them.

None of the stories in this game are about the person experiencing them, and that’s what makes them so painful. Ned Goodwin isn’t really to blame for his son’s death. Certainly, he could have been a better father, but his real failure is not his proximity to a horrible accident, but his refusal to take responsibility for it. That’s the game’s point right there — it wasn’t Ned’s fault, but it was Ned’s responsibility.

Firewatch wants to talk about feeling responsible for something, taking responsibility for something that isn’t our fault because we are the ones who can when the need arises.

Did you pick up the girls’ beer cans around the lake? There’s no achievement for this, no objective tells you to do it and nothing notes whether you did at the end. But that’s what you’re here to do, isn’t it? To take care of this landscape, to look after it. You didn’t put the beer cans there, but maybe you picked them up because that’s who you are supposed to be in this game, the role Henry is trying to learn to play — someone who takes responsibility for the thing they’ve promised to protect, even if they’re not the one who harmed it. Someone who stops and picks up the pieces when no one else will.

Every part of the ludonarrative of this game is conveying the same message. Your choices don’t matter, not really, because the tragedy that is happening in Henry’s life doesn’t care about his choices, or Julia’s. It’s happening now, it’s not fixable, and no choice he’s ever made could have prevented it. However, your choices tell you how Henry copes with that lack of real control, and how he responds to the inevitable moment we all have to face in our lives: when we realize that random chance and factors beyond our control will eventually take away all of our choices.

The only thing that saves us in those moments is the thing Henry failed to give Julia: a promise that when the end comes, impersonal, people will stand together against it regardless of our culpability. We promise each other when we marry, when we have kids, explicitly. It’s part of the traditional vows — “for richer or poorer, in sickness and in health...”

What are we saying there if not “when the world is cruel to you, I will be kind. When the world is senseless, I will try to make sense of it with you. When time takes everything we are and robs us of everything we love about each other, I will remember this promise, remember the reasons I care for you today on the day when our reasons crumble. When the world is indifferent to you, I will take responsibility.”

Your Ending is Your Own

On the last day, you can find Henry’s wedding ring on his desk if you think to look before you leave. You can put it on if you want to, and if you do, it doesn’t change the ending a bit... except that the hand you raise to help yourself into the helicopter at the end has a ring on it, or it doesn’t.

It doesn’t tell you what Henry decides to do, because you already know. Did you leave the beer cans lying around? Trash the girls’ camp? Did you burn down the tent in the woods? Did you get drunk and paranoid searching for the secret government conspiracy, desperate to believe that there was some greater meaning to your petty irritations? Were you able, ultimately, to accept that most of the pain you experienced hasn’t happened because you deserved it, but because you were there, and it doesn’t alter your responsibilities in being there one tiny bit?

Your ending is your own. It’s in you, in whether you walked this path with Henry and came to any conclusions about what he should do next from your time in the woods. It’s in whether you felt his pain resonate with other hard choices you’ve made for people you love, other promises you’ve kept or broken, other times the world has shown you, again, that it will give nothing back, and you’ve chosen to keep pushing forward regardless.

The people asking for a definitive ending, or more detailed resolutions to the game’s side-plots, are feeling the same hurt, confused ache for meaning and agency that someone losing a loved one to early-onset dementia is feeling (though obviously to a different degree; I’m not trying to draw any parity between a fictional experience of grief and a real one I have not experienced). They want there to be a reason, but there’s not. They want to say, “But I’m innocent, they are innocent, we didn’t deserve this!” But there’s no judge to tell, no one who could reduce your sentence for good behavior. It’s happening, and you don’t get to opt-out, and looking for sense in it is a waste of time that only delays when you act to mitigate the damage.

The fact is that shit happens. We like to use our art to argue with reality about this, to imagine a universe where our choices shape the movements of the world, and when a piece of ostensibly escapist media presents us with an experience that echoes the powerlessness and fatalism we can get perfectly well at work, thanks. It’s understandable that most people won’t like it.

Certainly, Firewatch isn’t perfect. No art could or should be, but it attempts to evoke an experience that is rare in its medium and rarely expressed in these terms and with this delicacy and tenderness. That amount of investment on the developer’s part warrants at least as much commitment on mine, to push through a sometimes-frustrating experience and consider that the frustration itself might be an intentional effect, to a purpose. This is the real poetry of interactive art, its purposeful meta-textual attempts to guide the player in engaging with it from the best angle in the perfect frame of mind.

Firewatch is about how we deal with what we can’t escape, and what we owe to ourselves to uphold our commitments. We can decide that we are a victim and flee from everything that once made us happy just to avoid a fate that feels unfair. We can fully identify ourselves with our suffering and nurture it close to us forever, like a rotten tooth, always prodding at it to see if it still hurts just as much.

Or we can decide that being here, making the choices we can, and getting to continue taking part and connecting in human life, is reason enough to take responsibility for protecting fragile things and fixing broken ones. We can decide that it’s not about fault, being a hero, winning, or getting rewarded. It’s just about the truth. We’re the ones who are here now when help is needed, and if we don’t help, no one else will.