What Defines 'Survival' in Survival Horror?

Exploring the relationship between the player's internal and external struggles

Following Sony's most recent State of Play, the Silent Hill 2 remake has been a hot topic. People are focusing on various aspects (attention to details of the world, character redesigns, and more), but there’s one thing I think deserves more discussion: the redesign of the game's combat. Specifically, as it relates to engaging with enemies, this redesign seems to bring it up to the standards of Resident Evil 4. However, this clashes with the act of survival horror and provides the easiest distinction between action and survival horror design.

Power vs. powerless

My book and previous articles have extensively explored the distinction between power fantasy in horror and action design. Depiction and intent are important aspects to comprehend if you’re designing a horror game. Some people will say any game that features “monsters” is supposed to be scary, but we know that’s not the case. Doom Eternal has monsters...demons actually, but the player is not supposed to be scared.

What Resident Evil 4, both the original and remake, brought to the table was a rethinking of what you could do in a horror setting. In both versions, Leon is very capable; he can nail headshots, perform wrestling moves, and counter almost anything with his knife. So, while the player is in a spooky area, fighting spooky people, the game does not intend to be scary. The player is or should be in control of any situation.

In the Silent Hill 2 remaster trailer, I noticed a stronger emphasis on i-frame dodging, James being able to stun enemies before delivering a finishing blow like Leon, and a nurse auto-countering James in the extended trailer after excessive attacks.

It’s easy to think that improving the combat, or creating new combat mechanics, is going to make the game better. However, it also clashes with one of the most essential tenets of good horror design — you do not want to be fighting.

Overcorrecting horror

Two over-corrections happened with horror design in the 2010s. After the success of Resident Evil 4 in the prior decade, designers started to heavily emphasize the idea of combat as a focus for horror, as evidenced in Dead Space and, later, the Evil Within games. Even F.E.A.R., which is still highly regarded, went for this idea of a military shooter meets Japanese horror.

The other was a complete denouncement of the prior trend by smaller and indie studios. One of the most famous for that time was Frictional Games, who after the release of the Penumbra series went on to hit it big with Amnesia: The Dark Descent. In interviews after the fact, the co-founder often said they wanted to move away from combat/fighting in horror games as it was hurting the experience. Soon after, every single indie developer went a similar route with the likes of Five Nights at Freddy, Outlast, and more like-minded horror games than I can count today.

Some studios may put combat in as a pseudo-boss fight or end-game option, but for most of the gameplay, the player is not fighting or engaging with the enemies. Looking back on both styles, the developers are wrong for varying reasons.

With the action side, the more the player is allowed to engage with enemies from a position of power, the less horror there is. You can tell that a game is not intended to be scary, like in Dead Space, where most of the encounters focus on arena fights and emphasize combat. With The Callisto Protocol, I shared in my review that it was a good action game, but a terrible horror game because of combat devolving into a dodging mini-game.

From the other side of the equation, having no combat or direct interaction with the enemies presents a different problem. It creates this black-or-white state wherein the player is either 100% safe or 100% dead. When the player reaches a point where they can’t reasonably do anything else, they experience a shift from a sense of horror to a sense of frustration, as they get stuck at a spot repeatedly.

This style of horror game becomes overly repetitive in terms of gameplay since there is only one “right way” to navigate these encounters. If you watch high-level play of something like FNAF or Outlast, you’re not engaging with the game anymore. You are performing a fixed set of actions designed to counter the AI behavior of the enemy, not the enemy itself. In the past, I’ve equated horror like this to a haunted house, and in my opinion, that’s not good horror design.

With the footage I saw from Silent Hill Remaster, the developers are obviously leaning towards the former, but this betrays several aspects of survival horror design that I do not see a lot of developers doing justice to.

Scraping by

Survival horror, as the name implies, is about survival. This is not supposed to be about the Doom Slayer ripping and tearing through monsters, just as it isn’t about someone being chased by cannibalistic monsters and deciding not to pick up any of the knives, swords, clubs, or chainsaws they find around.

There is a very narrow place for where combat should fall in a survival horror game. It is a tool, but not “the tool” the player can use. If combat is too powerful, then it becomes the best option in any encounter if the player can just fight their way past everything. If it’s too weak or nonexistent, then the player doesn’t have a way of interacting with the creatures. A good example of this philosophy would be the survival items from Resident Evil 1 Remaster. The player can fight enemies a bit more safely than before with them, but their use is still limited.

What you want to see in a good horror setting is that fighting is allowed, but you do not want to be doing it. There must be a credible risk to the player’s health, resources, or both. The horror present in these games shares similarities with the horror found in all Souls-like games, where players find themselves in unfamiliar territory with a great amount of souls at risk. The possibility of losing everything in any confrontation or scenario is a constant threat. Combat needs to be chaotic, not something that you can hone your skills at, such as in Sekiro, where there is a legitimate challenge to get through the game without injury.

That also means designing enemies whose only behavior is not either “run at the player” or “run very fast at the player.” Nemesis and Mr. X from Resident Evil 2 and 3 Remakes are close to what I’m looking for, but they still feel more like a phase in the level design, rather than an active enemy. Once you know their behavior, they stop being a threat. Looking at the footage from the Silent Hill 2 Remake trailer, the nurse was performing the same three-hit combo twice, which leads me to believe that combat will be mechanical in that respect.

In a surprising twist, the closest a game has gotten to what I’m looking for in survival horror would be Amnesia: The Bunker. The beast that stalks the player is something that can be engaged with in multiple organic ways. You can set traps, use noise as bait, or just shoot the damn thing until it retreats. Being able to fight the creature or use the environment to your advantage gives the player many options and takes me to what I want to see as an evolution of horror.

The path toward evolution

What I’m looking for as an evolution of horror design is not about making the game hard to control or have janky movement, but giving the player a variety of weapons and means of survival. The goal is to provoke complete terror in them, discouraging any attempts to use these weapons and means against this chilling threat. Returning to the idea of Doom and push-forward combat, a wild thought came to me: can you create a survival horror game that is terrifying even if the player has unlimited healing items and ammo from the start?

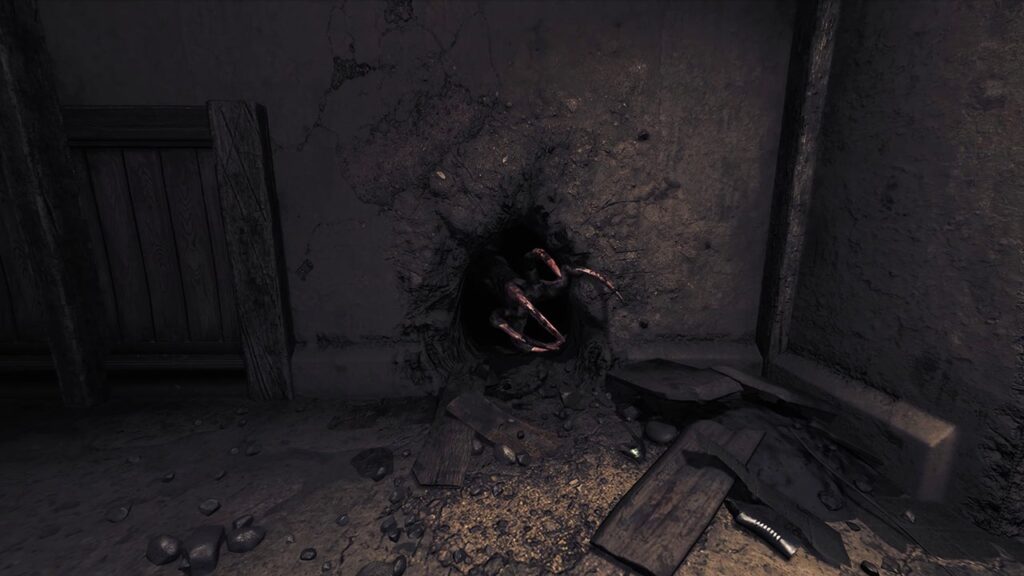

I want the enemy designs to have the same freedom to use the environment as the player does, allowing the trapper to become trapped and then turning it around on the player. I’m tired of games that only have fixed breakable sections where an enemy can show up. I want the player to feel unsafe from every and all directions.

Source: YouTube.

In horror design, the player’s internal struggle is just as important as their fight against enemies. If the player is too powerful or too weak, the horror game loses its impact.