Wayward Strand Review

Enjoy the quiet and making new friends

You know, sometimes it’s nice to take in the quiet moments. Just be content sitting with another person, maybe chatting a little, maybe just sitting in silence and enjoying each other’s company. Wayward Strand, the debut game from Melbourne developer Ghost Pattern, is a narrative adventure game that makes full use of the kind of quiet, contemplative moments that are rare in video games.

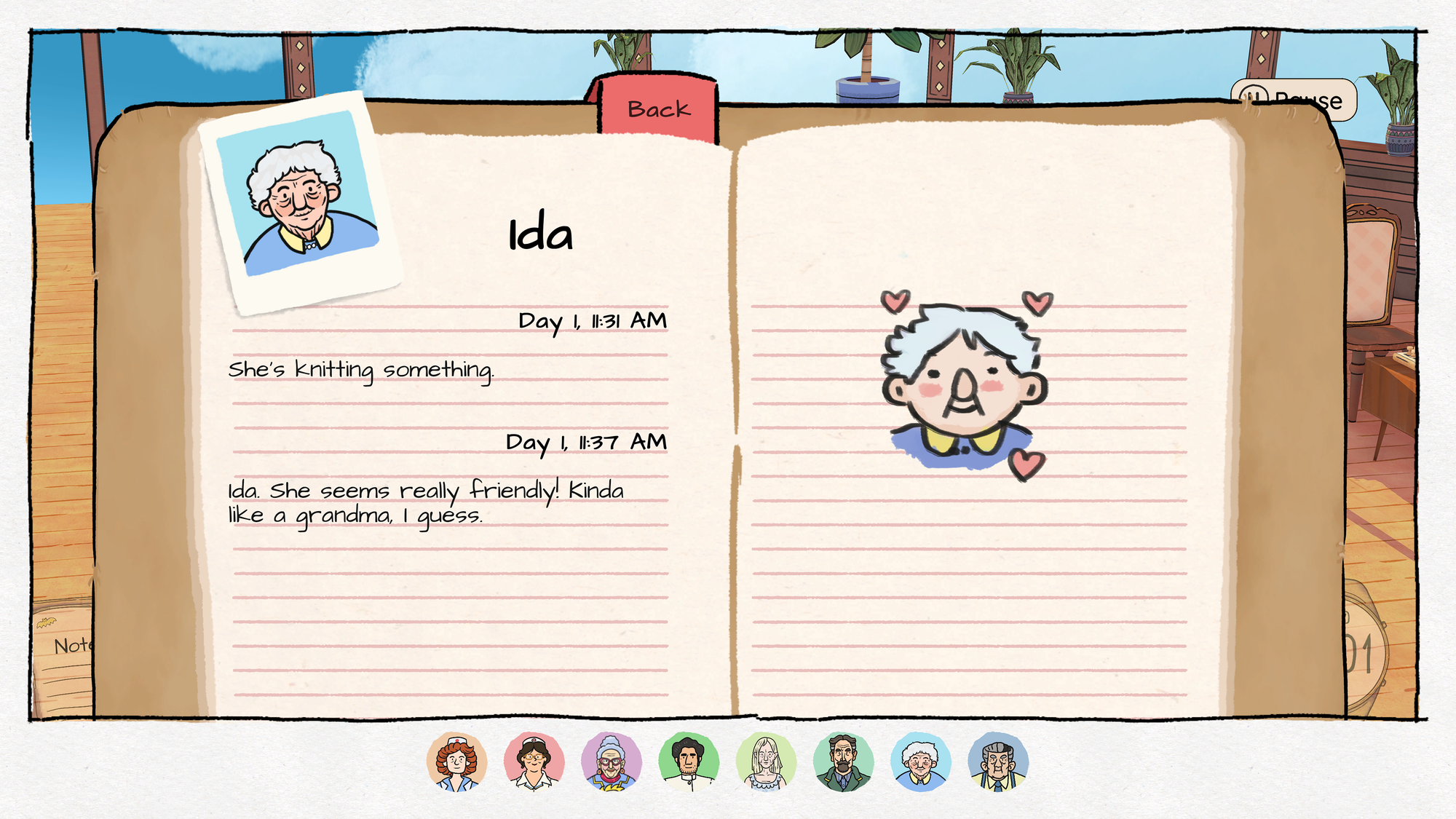

Wayward Strand takes place in Australia during the summer holidays of 1978, on a washed-up airship that has been converted into a hospital for the elderly. You play as fourteen-year-old Casey, a high school student, budding journalist, and daughter of the head nurse at the hospital. She has been tasked with keeping patients company during her time on the ship while her mum works. Over the course of three in-game days, you will connect with the six patients, as well as the busy hospital staff, providing fuel for a future article by Casey, who will frequently scribble notes (and pictures) down in her notebook.

The structural hook for Wayward Strand is that each day moves ahead on its own, and you have to work around the daily workings of the hospital. There are no guiding objectives other than ‘make yourself useful,’ so it’s wide open as to how you spend your time during the day. It’s not unlike the system from Inkle’s time loop visual novel Overboard (which shares an engine with Wayward Strand), but it’s a set three days rather than a single day on repeat, and you’re befriending old people instead of hiding a murder. The patients will move around as they visit each other or go grab some soup for lunch, and the staff scurries about on the three-story airship.

The open structure means that the main motivation to push forward is your investment in the cast of characters. Thankfully, each of the patients is engaging enough through a combination of their personality and backstory, which has to be gradually prised out over the course of the game. How much effort it takes to get to know the patients depends on how outgoing and open they are towards Casey, to begin with.

Fortunately, the patients are the stars of the show. Some warm to Casey right away, such as the verbose writer Neil Avery (voiced by Australian film stalwart Michael Caton), who gladly takes the young aspiring journalist under his wing. There’s also the kindly Ida (voiced by Anne Charleston, better known as Madge from Neighbours) and the sometimes gruff but still open Esther. On the other side of things, there’s the mute Tomi, the former doctor Margot, who is quite grouchy but also quite ill, and the Austrian Heinrich Pruess. You also can spend plenty of time with another teenager, the Indigenous railcar operator Ted.

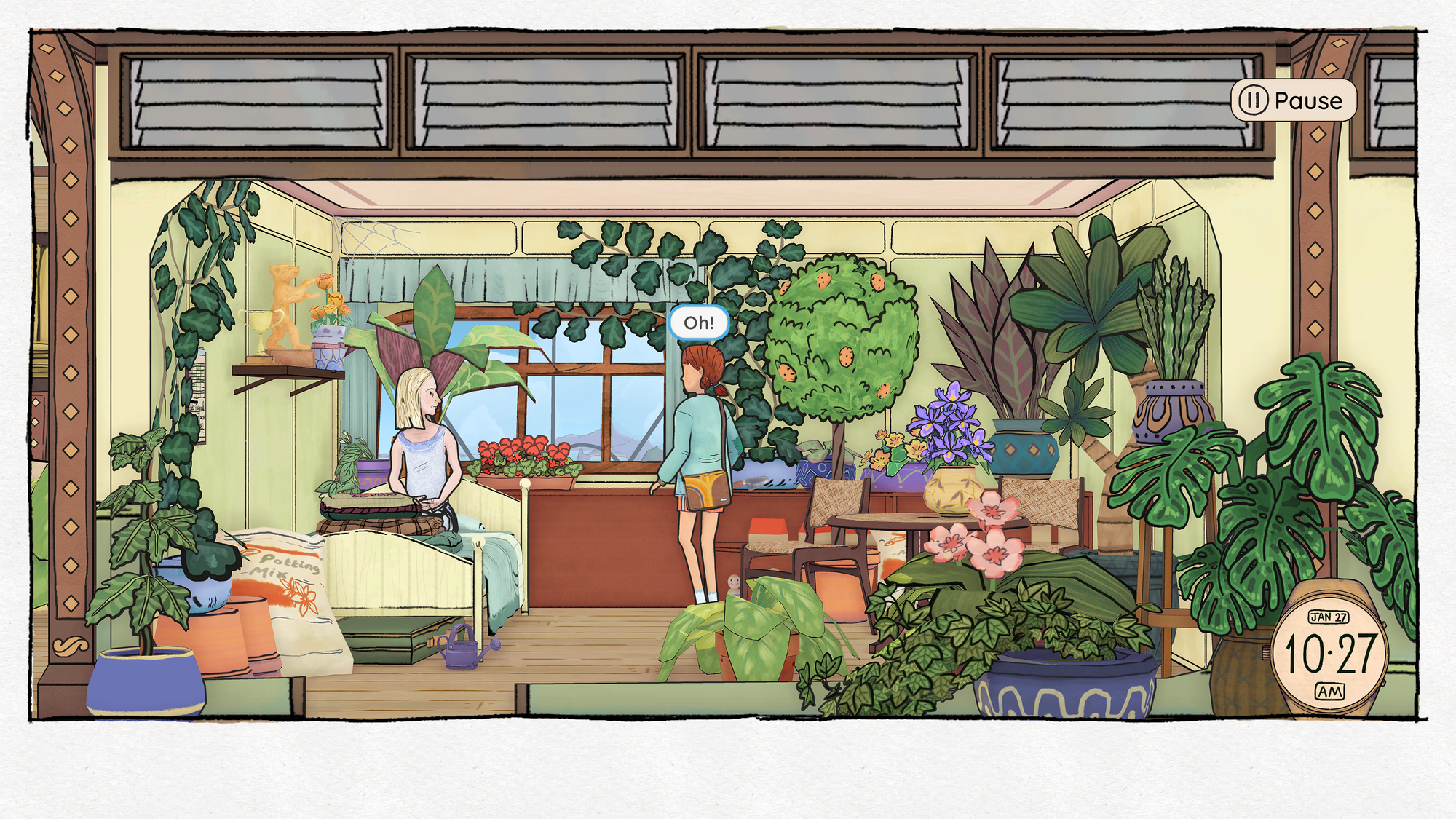

What you will spend most of your time doing in Wayward Strand is bouncing from patient to patient, who are often in their rooms. It’s worth mentioning at this point that the game looks great with its combination of picture book art style mixed with 3D models. I say this now because each patient’s room is like a highly detailed diorama, filled with things that help fill out a patient’s story. For example, Tomi’s room is filled to the brim with plants and flowers, as well as a curious trophy that Casey takes a keen interest in, while Mr Preuss’ room is covered in paintings and souvenirs from his family in Austria.

When you visit a patient, Casey will sit down beside them. Sometimes she is welcomed and conversation flows, sometimes you have to find an item in the room to ask about to try to get some discussion going. You always have the option to wait for the other person to speak, even with Tomi or a sleeping patient. It’s reiterated by Casey’s mum and the staff that the main thing the patients want is company, and your patience is often rewarded, with patients becoming more friendly towards Casey and giving her more of a glimpse into their backstory.

When I first started playing Wayward Strand, I was running all around the ship, trying to see what storylines I could emerge as fast as possible. I thought that with a limited time frame, I wanted to make headway in whatever the big mystery there was to uncover. But the thing is, it’s not that kind of game. Wayward Strand is a game made up of a series of small moments. Quiet, contemplative moments. Funny moments. Moments of fondness as the patients recall their adult children or their late spouse.

There are storylines that play out over the course of the three in-game days, and they provide the requisite drama, but the game’s writing really shines in the smaller interactions that make up a large portion of the 5-hour runtime. Wayward Strand does a fantastic job of recreating the feeling of spending time with a grandparent – conversation may not exactly flow, but what is said can be a fascinating insight into someone who lived a whole life before you were even born.

Wayward Strand deserves full credit for telling the stories of elderly people, stories that aren’t really seen in games, and doing so in an interesting and engaging way. You may find yourself picking up the phone to organise a catch-up with your grandparents after playing this game, and see what stories they have to tell.