Comparative Criticism #1: War and the End of Humanity in Final Fantasy Type-0 and Apocalypse Now

Examining the concept of war as the failure and end of humanity

If video games can be an art form, video game criticism is a way to connect them to life. Art has a close connection with life (life imitates art and art imitates life), so works of art can inspire, interpret, and express different aspects of what underlies the real world. In this Comparative Criticism series, my goal is to show how video games and other forms of artistic expression complement each other to give us a deeper and more complex perspective on actual phenomena represented or that jump out of fictional worlds.

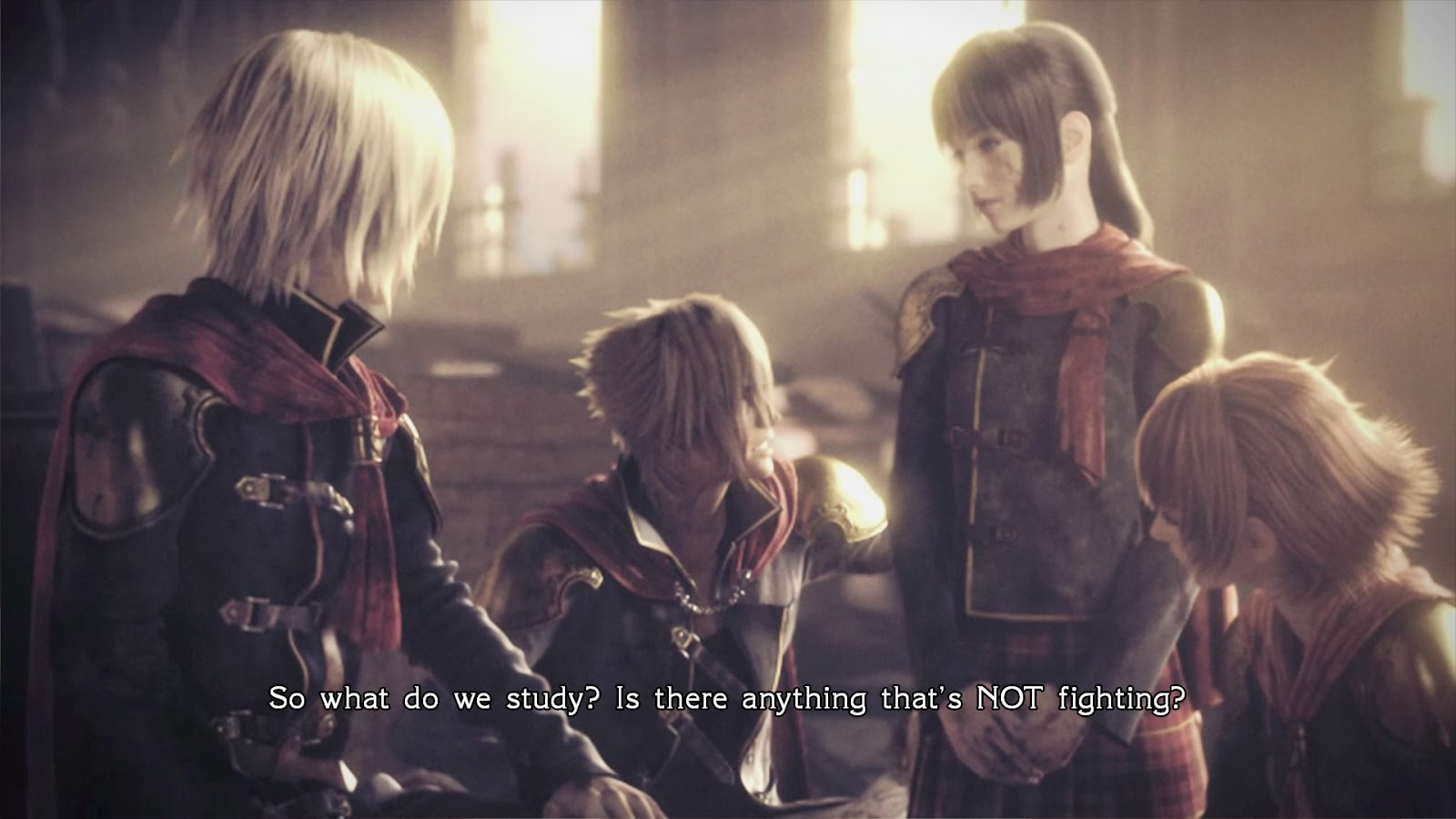

You might wonder what connection we can make between the two works I mentioned in the title of this piece: a historical fiction film about the Vietnam War and a science fantasy JRPG with a group of young students trying to save the world. What else can they have in common but simply war? You will see what they have in common is not only war, but its effects on human sanity and on humanity itself. Not by chance, the director of Final Fantasy Type-0, Hajime Tabata, mentioned the movie Apocalypse Now as one of his dominant influences for this Final Fantasy game.

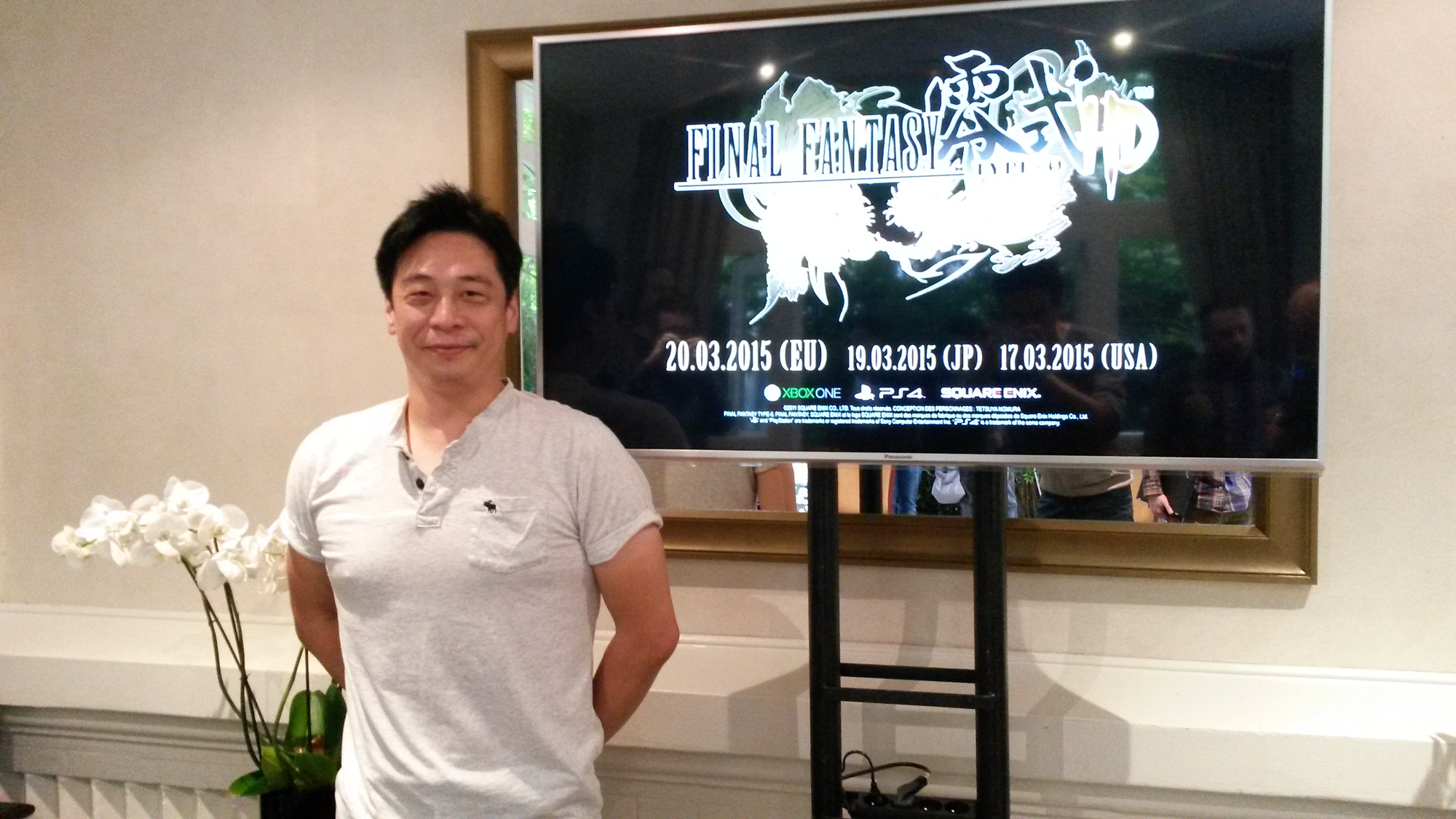

From left to right: Hajime Tabata (Final Fantasy Type-0 director); Francis Ford Coppola (Apocalypse Now director). Sources: FFWorld; Glamurama.

"When I started working on the game, I was watching Apocalypse Now. That atmosphere, with war in a fantasy setting, stuck in my head. So, when I started working on the game, I tried to incorporate those elements into the fantasy world of Type-0. I also wanted to create a sense of tension and madness, and I think that's something that the movie conveyed very well."

— Hajime Tabata, Dengeki PlayStation, Vol. 547, 2011, p. 65.

However, it is important to highlight the difference between “comparative criticism” and “comparative review.” The first is a critical analysis of common phenomena in two or more works, the second is a comparison between two or more works in order to recommend one and show which, in some respects, is superior to the other. Furthermore, as “comparative criticism”, our approach can freely address spoilers of the works being compared, whereas in a “comparative review” this is often avoided, as the person is supposed to be reading to see if it is worth buying.

Although much more common in literary criticism, I believe that comparative criticism can also be fruitful for video game criticism, and this piece is my first experiment in this approach, which was also suggested by Ian Bogost. My approach is not exactly the same as that proposed by Bogost, but I believe it has a lot in common as it analyzes the meanings behind both works and that relates to the phenomena of human experiences, such as war and sanity, on this piece.

"...such a comparative videogame criticism would focus principally on the expressive capacity of games and, true to its grounding in the humanities, would seek to understand how videogames reveal what it means to be human."

— Ian Bogost, Unit Operations: An Approach to Videogame Criticism, 2008, p. 53.

The Impact of War on an Individual Scale

If we look at the classic cosmological distinction between "chaos" and "order", war is a curious phenomenon, as it appears to make order serve chaos. Culture, army, politics, economics, and even morality are used to promote chaos, a chaos that will engulf all these things. By making all those social structures in which the human inhabits, war makes him encounter his finitude and perceive himself as “a postponed corpse”, as the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa said when trying to define the human.

It is very difficult for humans to assume their existential finitude, but life is a constant learning experience for them to recognize their mortality. Life inevitably throws us one loss after another, forcing us to forget memories, let go of personal possessions and say goodbye to loved ones. Then the day will come when we will have to say goodbye and forget about ourselves. Finitude is sad, but also beautiful because having an end means being able to let go of yourself. However, preparing for this ultimate event is the work of a lifetime, and war, like an implacable order from a general, demands that humans, within the absolute chaos, are always prepared to face death.

This is unceremoniously played out at the beginning of Final Fantasy Type-0 as if warning the player of what lies ahead. Perhaps the most beloved and innocent symbol of Final Fantasy, Chichiri (a Chocobo), is shot and killed in the first cutscene of the game, and Izana Kunagiri (21 years old) tries for hours to prepare to face death along with his Chocobo in vain.

The film Apocalypse Now also opens with despair and desolation, not someone about to die, but someone who is about to go on a suicide mission to find and kill Colonel Kurtz (played by Marlon Brando), an officer gone rogue who is now leading a guerrilla warfare in the Cambodian jungle. In the opening scene, the main character in charge of this mission, Captain Willard (played by Martin Sheen), is alone in a hotel room in Saigon, South Vietnam. He is struggling with his own internal demons, drinking and smoking compulsively, while having flashbacks of his previous experience in the war.

From left to right: Final Fantasy Type-0 HD; Apocalypse Now. Sources: operationrainfall; Scott Myers (via Medium).

Obviously being prepared for death without having lived long enough for it is an impossible order to fulfill, and condemns humans, even with all their efforts, to fail miserably in everything but losing themselves amid chaos. In this context, the tendency is for humans to lose their mental health and eventually even the essence of their sanity, their perception of reality.

Many psychological problems caused by war are known, such as depression, trauma, and anxiety, and can have different reactions in different ways, depending on the individual. Izana’s death provoked a blind desire for revenge in her younger brother, Machina Kunagiri (age 17). On the other hand, the young protagonist Ace has hallucinations and visions of people he has seen die on the battlefields. He tries to overcome this pain by isolating himself and training obsessively.

Apocalypse Now addresses these themes more intensely. The hallucinations, in particular, are already present in the opening scene of the film that we mentioned. Another notable scene is when Willard and his team are on a beach to encounter surfers who are fighting in the war. The leader of the surfers (played by Robert Duvall), seems completely detached from reality, obsessed with finding the “perfect wave”, even if it means risking his soldiers’ lives. Duvall’s character is an example of how war can affect people’s mental sanity in different ways. Additionally, Colonel Kurtz (the target of Willard’s mission) presents himself as a charismatic leader who has become completely insane and barbaric, portrayed as a man who is at war with himself.

From left to right: Ace dreams of Izana, Final Fantasy Type-0; Apocalypse Now. Sources: finalfantasy.fandom; centerforsurfresearch.

War makes everyone directly or indirectly witness violence, loss and brutality, including the youth of Final Fantasy Type-0 and Apocalypse Now. Something that aggravates the psychological situation of the protagonists of Final Fantasy Type-0 is the fact that events force them to fight against friends and acquaintances, as is the case of Machina’s battle against her best friend, Rem Tokimiya.

In Apocalypse Now, the film’s protagonist also deals with humans who have lost touch with reality. When Willard eventually meets Kurtz, he discovers a man who is seemingly insane and disconnected from the world he was previously a part of. Kurtz has fanatical followers who worship him as a god, and he himself seems to have transcended humanity.

Insanity and death are inextricably linked, not simply two outcomes of war, but two sides of the same coin. Losing your sanity meant losing yourself within yourself; losing your life means losing yourself nowhere. If we assume that war is only made by humans, this is because they are supposedly the only ones capable of being conscious, and also the only ones capable of losing themselves to the point of taking humanity nowhere.

The process that takes human insanity to its end is what we can experience in the works of Tabata and Coppola: the process of chaos. Chaos has several faces, such as violence, brutality, unpredictability, randomness, impotence, vulnerability, insecurity, among other aspects, all present in some scene from Final Fantasy Type-0 and Apocalypse Now. All these faces together represent the weaknesses and failures of humanity in the face of which it is difficult to find hope for moving forward. The hopelessness is even more powerful when it involves teenagers and children, and both directors use this element.

From left to right: Final Fantasy Type-0; Apocalypse Now. Sources: coronajumper; fotogramas.

The Impact of War on a Social Scale

What is special about humans is not who they are as individuals, but what they are as a species and as a society. If there is hope, it lies in the unity of humankind, not in its individuals. Final Fantasy Type-0 and Apocalypse Now test that unity. For this reason, teamwork as students (Class Zero) and as soldiers in the same party is a fundamental part of Tabata’s game design for Final Fantasy Type-0, allowing the player to switch and evolve several playable characters.

Unlike Tabata, Coppola is not directing a game, but in his film, he uses camera alternation to give a collective perspective on the war. In this way, the audience has an experience not only of the traumas of a protagonist but of a crisis that affects all of humanity. There is a scene where Willard and his team encounter a crew of injured American soldiers who need to be rescued. During this scene, the camera alternates between several characters, including Willard, his soldiers, the wounded soldiers, and the Vietnamese enemies who are attacking them. This camera alternation helps to create a sense of urgency and tension, allowing the audience to see the situation from different perspectives.

From left to right: Final Fantasy Type-0. Sources: coronajumper; alternateending.

In the previous topic, we saw how war psychologically affects individuals in Final Fantasy Type-0 and Apocalypse Now, even harming the mental health of their characters. However, the most interesting thing about these works is how they deal with the repercussions of war on a social scale. We can highlight mainly the themes of alienation, deception, morality, and war propaganda. Here are some examples in Final Fantasy Type-0:

- Alienation: In the world of Final Fantasy Type-0, society is divided into distinct classes, with the elite students of Akademeia Academy (the “Class Zero”) considered superior to others. This division creates a sense of alienation between the main characters and the rest of society and leads to conflicts between the two classes*.

- Deception: The government of the nation of Milites claims neighboring nations represent a security threat and that war is necessary to protect the people of Milites. However, the characters discover that this is a lie and that the real motivation for the war is the control of the crystals that power magic.

- Morality: Final Fantasy Type-0 portrays war as a morally complex struggle, where there’s no clear right or wrong side. Class Zero characters are forced to question their own actions and evaluate the validity of war goals**.

- War Propaganda: The nation of Milites uses media and propaganda to influence public opinion in favor of the war. They make the people of Milites see the war as a just fight by dehumanizing and portraying the nation's enemies as cruel. Cid, who presents distorted news and pro-war propaganda throughout the game, represents this propaganda.

** In one mission, Class Zero was tasked with killing civilians who have been labeled "traitors," leading to an internal debate about the morality of this action.

Final Fantasy Type-0. Sources: wsgf; finalfantasy.fandom (second and third images); coronajumper.

Apocalypse Now also contains these same themes. Willard has to make tough decisions in several scenes of the film, involving moral dilemmas. Deception is also a recurrent theme, and perhaps the best example is the previously mentioned case of the cult of Colonel Kurtz, or as part of war propaganda, also very present in the film. There is a scene in particular where Willard arrives at a military base filled with slogans and war propaganda music that is intended to increase the soldiers’ motivation.

Compared to Final Fantasy Type-0, the movie Apocalypse Now stands out mainly in the concept of alienation. Unlike Tabata’s game, where most of the characters are part of their nation’s daily life, Coppola’s film has characters that are far from their nation. They are removed from the environment they exist in and often struggle to understand their emotions and beliefs. This is especially clear in the character of Kurtz, who completely withdraws from the world and develops a very personal and nihilistic view of war.

The Human and the Apocalypse

If for some reason, you were expecting a happy ending for these stories, you are deeply mistaken. This is also part of the dark and daring side of these works (especially with Final Fantasy Type-0 — no other game in the series dared to make such a sad ending). The war begins and ends with the end of humanity. If a war starts, humanity has already failed, and then only the dead can see the end of the war.

Final Fantasy Type-0 portrays a cyclical tragedy in the relationship between flawed and warlike human nature and the course of wars. We can observe this cycle in four stages:

- Loss of Hope: The devastation caused by a prolonged war has disheartened the characters and taken away their hope for the future of humanity.

- Imminent Threat: A giant meteor is on a collision course with the planet, increasing the sense that the end of humanity is imminent and inevitable.

- Acceptance of the End: The characters must accept that the end of humanity is inevitable and use their remaining time to fight for a better future for those who survive.

- The Discovery of the Cyclicity of the End*: The extinction of humanity may be cyclical, with events like the meteor occurring in a predictable pattern, unless there is a fundamental change in how humanity deals with conflict.

These four points are also present in Coppola’s film, but they are not exactly in a cycle, but scattered in a more chaotic way. Furthermore, the realism of Apocalypse Now, in contrast to the fantasy of Final Fantasy Type-0, gives the film a greater impact of brutality and violence among humans to the point of threatening their existence as a species (including environmental tragedies); there is no hero to win this journey.

Interestingly, the idea of a tragic cycle was also thought up by Coppola. the film also suggests a cyclical nature to human existence, with the end of one era paving the way for the birth of another. The film’s last scene symbolized this, in which Kurtz’s compound ends up destroyed and his followers killed, while the native people emerge from the shadows to claim the land for themselves. This suggests that, while the end of humanity as we know it may be inevitable, there is always the possibility of renewal and rebirth.

Final Thoughts

This was my first piece in the "Comparative Criticism" series. Following the influence of comparative artistic criticism, especially common in literary criticism, I intend to enrich the interpretation of videogames through this method. Especially comparing some interesting aesthetic experiences in video games to other art forms. Today we saw how Hajime Tabata (Final Fantasy Type-0) and Francis Ford Coppola (Apocalypse Now) addressed themes around war, such as morality, insanity, alienation, and other aspects, both on an individual and social scale.

At first glance, Apocalypse Now and Final Fantasy Type-0 may seem like very different proposals, while one is historical fiction and the other is fantasy, but the differences are only on the surface. On the other hand, the deepest intersection between these works seems to be in how they conceive the chaotic nature of war. The beginning of the war coincides with a period of decadence for humanity, and the war is represented as a journey for which there is no hero and whose end can only be witnessed by the dead.