Twilight of the Emeralds

Unraveling the story of Sonic 06

The premise of Sonic the Hedgehog (2006) is that a theocratic constitutional monarchy, after studying the powers of its theocratic reason (the Solaris god), ends up imprisoning and studying said god as a systematization of a time-controlling tool so it can serve the interests of the State. We find out later that it’s even more selfish than originally thought: the king only wanted to see his dead wife again. It’s implied that its biggest capital generator, apart from tourism, is the creation of clocks and watches. This is something that reflects the divine idealization: the god of time blesses this city, and the city, in turn, thanks his blessing by intertwining it in its craft.

The human intervention transforms this entity, previously benevolent, into something vengeful that, due to its timeless-y attribute, wants to destroy the world because he sees the errors of said humanity. I use the “humanity” word just as a simplification since a lot of its sentient beings aren’t human, nor follow a standard genealogy from other species — we can just assume that they are carefree manifestations, as bats, hedgehogs, foxes, etc) throughout all time: past, present and future.

After that, the plot branches in two different, although co-dependent, start points. In the future, where everything is destroyed, an argent hedgehog looks for the reason for the apocalypse that tore down his world. During the present time, a blue hedgehog takes a walk (run?) through a city and saves a princess from being kidnapped by a trans-humanist (trans-creaturist?) scientist.

The story that follows is a literary demonstration of that timeless god, who is able to see the whole chronology in all of its forms, just like the player who plays all of the stories independently from the game’s own temporal frame. For example, the malignant projection of Solaris in the future, named Mephiles, tries to persuade Silver, the argent hedgehog, to go back to the past and kill Sonic, the blue one. In the past, Sonic and Princess Elise become more and more intimate so Elise would cry when Sonic dies. The key to the plan is actually inside the princess: during the Solaris experiments, part of the god’s being was trapped in her and will only be freed through her tears, which is what caused the apocalypse.

Apart from all of that, a third hedgehog, Shadow, finds out that Mephiles took his appearance in the future because he would be betrayed (and crucified!) by his friends and the rest of humanity. That would be caused by the lack of understanding of the world and its fear of the unknown — both things easily understood by a divine being, who sees himself in Shadow and takes his form in flesh.

Following all that contextualization, there is a deep exploration of Silver and Shadow because they were characters created in a different era than Sonic. Sonic doesn’t need an arc - he’s Sonic, and his whole personality was created through silent actions and his appearance. He puts on his undaunted face and runs forward, fearless. He looks at the camera, impatient, wanting for our command so he can finally move, but at the same time, he is moving without any button presses, tapping his feet. He doesn’t need us to control him. He lets us. He pretends that he needs our agency, but we’re just the younger sibling pressing buttons in a controller that isn’t even plugged in.

Shadow was created ten years after Sonic. For Silver, it was fifteen. Neither of those could take any action that wasn’t at least tangentially related to certain plot utilitarianism. They were created as Characters with personalities, arcs, lore, and objectives. They can exist in a modern storytelling context with no effort — they are the results of said modernism and how the videogame medium has evolved — they are characters from epics. Sonic isn’t. Sonic, and with absolutely no shade intended here (actually, it’s closer to appreciation), is a cave painting.

Sonic was born from the willingness to do something on our digital cave wall just because we could. His simplicity is raw, and was essentially created through that simplicity, the willingness to just do. He can be a metaphor, a vehicle, but at the start, he was just Sonic, a recording of a creative spark not that different from wanting to draw a mammoth in the Rouffignac cave with charcoal just because we realized that we can use charcoal to draw.

He can’t exist in Sonic 06. The fabric of reality (both the literal reality as in the software and the imagistic narrative reality) can’t bear Sonic’s presence. He tries to adapt: putting up dialogue, lessons, trying to make him stick to the walls during a loop, putting a spring in the exact place he would need it to reach his objective, but the conclusion is that Sonic is just an intruder, an outsider, a being that shouldn’t be where he is, and whose energy weakens the structure of every building block of the piece. The game starts cannibalizing its own form because Sonic’s reality exists in a very different plane.

In Twilight of the Gods, Nietzsche describes, alongside a thousand other aphorisms, two kinds of man. There is the ubermensch (the one who acts according to his instincts and denies the morality and reason that were applied to the Western world by the plague of Christianity) and the Christian, someone who’s weak and has no agency, believing that the world adapts to himself because God thinks he’s important enough to alter reality just for him. Sonic is both of the archetypes at the same time. He follows his instincts, communicates using aphorisms (insensitive ones, sometimes), wants to have fun, and denies reason and morals just like the ubermensch — however, the whole world adapts to him, physically, through fear or despair. The world appears as his feet need it, with roads and springs and jumps, and it also adapts emotionally to his empty maxims, never disrupting his flow.

There are clear reasons and lessons to be learned from having Silver and Shadow in the game: Silver is there to teach (and learn!) self-sufficiency. He’s naive and insecure, trusting anyone who gives him instructions blindly. This leads him to try to kill Sonic, and then to the realization that he would never be able to handle his own thoughts if he didn’t sacrifice himself. When Blaze, his best (only?) friend sacrifices herself in his place, she makes it explicit that he needs to learn things on his own, without anyone else telling him what to do.

Shadow, on the other hand, is there to embrace the loneliness inherent to his own existence: since he’s a different lifeform than everyone else, his fate will always be that others will repress him because they’re afraid. His climatic moments are when the villain shows him a vision of the future where he’s a prisoner and, instead of having his ego shattered, Shadow just realizes that time is everchanging and he can create, manipulate and deny any destiny foretold. He’s also strong enough to face that world without wanting to rain vengeance on it. Shadow’s arc has been evolving since Sonic Adventure 2, going through the confusion of being an artificial being, the despair of maybe being just a clone, the denial of the past after knowing of his own origins, and, finally, during Sonic 06, the conformity of always fighting because everyone else is too.

There is no reason, however, to have Sonic in this game (apart from the name, of course). Every dialogue written for him shows him as inconsequential and irresponsible. Zolani Stewart, in his “On Sonic 06” piece for Project ZEAL, says that Sonic 06 is a work about the fail-state of all of its characters: nothing works for anyone, including Sonic, and the characters need to learn how to deal with this perpetual failure that covers all of the game’s fiction.

I interpret the events in a different light regarding its protagonist: his inconsequential mind spreads to the game’s universe like everything else — his actions are inconsequential in the literal sense: they have no consequence. In a specifically curt scene, Sonic can’t get to a ship in time to save the princess. The ship hits a mountain on the horizon and explodes. Sonic lashes out, yelling “Nooooo!” and Silver appears immediately to explain that he can just go back in time and save her.

This is important because Sonic dealt with time travel in at least 4 games, and in this one, all of the narrative conflicts are stemming from the playfulness of time-traveling (non-linearity, “aha!” moments, paradoxes, etc) and he still despairs — because he doesn’t know anything that’s happening two feet in front of him. He just wants to run and jump and create springs and boxes when necessary. The princess falls in love with Sonic just for convenience’s sake, because they never talk about anything relevant. Sonic likes having her around because when she’s in his arms, he can walk on water. Elise, however, needs to learn how to deal with her trauma of smiling all the time (otherwise the world will literally end), while listening to advice like “Just smile!” from Sonic. It’s obvious that he’s not actually the one saying that. He needs to act like a character that doesn’t exist, deceiving every other creature so he’s able to eventually escape that fiction.

Sonic’s stages are simultaneously the ones with the best level design (enemy placement, different paths, etc) and with the worst navigation. Sonic can’t do anything other than running and jumping, so the stages reflect that: you never need to stop, and if you’re brave enough to risk death to find a shortcut, it also works. But they don’t look like real places. This is a normal feature of every 3D Sonic game, but the gap is bigger here due to Silver’s and Shadow’s stages, which don’t look like they exist solely for their protagonists to walk on.

Sonic’s stages are like the Christian that Nietzsche describes: if a cliff is too big, there will be a spring. Whenever a hole is too vast, a row of enemies will be perfectly placed for a sequence of homing attacks. When we try to leave that path, pressing a button during a loop, or when Sonic is running on walls, the game’s world doesn’t accept us anymore: we’ll fall, die, explode, lay perfectly still while upside down. We need to let Sonic himself exist in those moments, not us. During Sonic’s stages, the game won’t accept anyone else’s agency.

In classic Sonic games, there was a fun dynamic where the first stages (the closest ones to Sonic’s “natural state) would be more fun for the character: more springs, more loops, fewer enemies, secrets behind waterfalls, and in general a more automatized movement. As the games continued, the stages would become less natural and therefore less Sonic-serving: you need to stop more, handle mechanisms, unfair enemies, and unique mechanics that we had to learn.

It’s not that Silver and Shadow’s stages are diegetic monuments. They are also full of springs and boxes and things like that, but there are also challenges. We need to move those boxes around using Silver’s psychic powers, we need to rebuild bridges and stairs and we need to elevate rocks to navigate around. During Shadow’s stages, we need to use vehicles because the distances are bigger, Shadow is slower, and more focused in combat and his homing attack is more situational (it starts a combo and doesn’t connect to another homing attack). Their stages show that the world doesn’t serve them: they need to manipulate it (through mechanics, in idiosyncratic puzzles, that in the best moments seem as if they were solved by our cleverness, and not by game design); The way that the game holds their structure is also much less broken: not as buggy, not a lot of parts where we can’t touch the controller in fear of breaking the script. Silver and Shadow, being characters with story and objective, are more respected by the fabric that holds the game together.

After finishing the three stories, something unexpected happens: Sonic dies. Mephiles kills him, the princess cries, releasing the flames that were caged inside of her, and Solaris revives to destroy spacetime, ending the existence as a whole in the past, present, and future. We can’t avoid that. Solaris knew that that would happen anyway and chose to act according to his own determinism. Time stops existing and therefore he cannot read it anymore — he becomes just a force of destruction, possibly even irrational since his rationality came from the fact that some chronology existed.

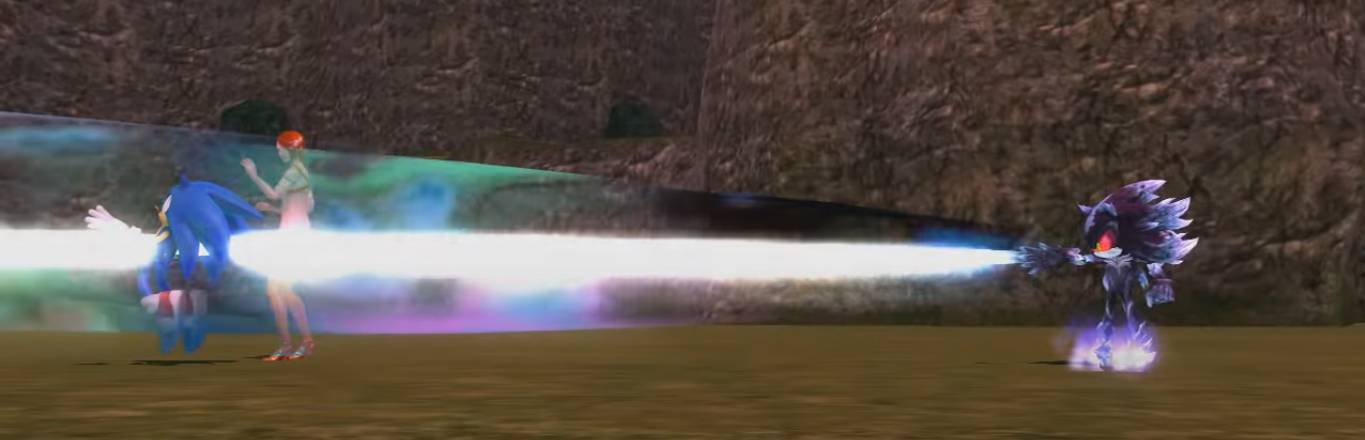

I stress that he needs time because the fact that time stopped existing makes him vulnerable: since he cannot read the situation anymore, Sonic’s friends can make unprecedented things happen in that reality. They find the Chaos emeralds and wish for Sonic to resuscitate and beat Solaris. Sonic is born again as Super (uber?) Sonic, shares his power with Shadow and Silver, and the three of them fight the demiurgical avatar of Solaris. The flimsy structure the game had to that point (following non-linear stories reflecting Solaris’ timeless eye) completely crumbles because the only way for Sonic to exist is to desecrate his own being in a world that can’t handle him. As the description of Nietzsche’s ubermensch, Sonic demolishes any chains trying to make him exist in a non-ideal state (death), forcing the world to adapt to himself or cease existing.

After that, at a non-specified point in time, Sonic and Elise meet each other in a different plane. Elise says that the only way to make everything go back to normal is to extinguish the flame of Solaris and, therefore, all of the game’s events. Sonic says once more that she should just smile, something that doesn’t make sense in or out of context apart from making it even clearer that this Sonic doesn’t exist: he’s a silhouette, a toy, a passing figure trying to use the form of a mascot, leaking out of that reality and doing everything to break it. When they put out Solaris’s flame, the game goes back to the opening scene: Soleanna’s festival, the princess walking, and Sonic running around the city. However, there’s no Eggman trying to kidnap her this time, and there’s no father committing deicide to save his wife. Sonic passes through the city and they never meet. Never met.

Sonic 06’s biggest legacy — its existence — is erased by its own main character so he can keep existing in other worlds, walking around them, searching for something that embraces him as he was embraced 30 years ago. Shigeru Miyamoto once said that all Mario characters are actors and actresses, so they can exit in any possible context. Sonic is too stubborn for that.

The game was created as a celebration of the hedgehog’s 15 years of existence. In 2023, it’s been 17 years since it was released. The game is so broken because the team also was: Yuji Naka left in the middle of the project, the game was rushed to coincide with the PlayStation 3’s release date so kids could get the game for Christmas, and the whole “new generation” problem for a mascot that is so extremely bound to his own time. The discourse around the game didn’t change a lot: it has always been received with mockery, and it was always the nuclear launch code to any YouTuber losing relevance. It’s surreal that we are still getting Sonic games after this one, and in its own context, it’s also weird that there were Sonic games before it. It’s a trinket so specific to a particular period that, like its own main character, doesn’t feel right to exist in our own reality and our own canon of what a videogame is or can be.

In Sonic 06, Sonic himself is a time traveler, forcing himself to adapt to a series, a commercial product, a franchise, and expectations that don’t suit him, that are not contemporary to him. The game’s axiom also doesn’t suit him, creating fissures and cracks wherever he goes, never having enough time or technical expertise. Sonic 06 is a game in conflict with its own main character, and therefore doesn’t have any basis to work with anyone else: the only way of handling it, and Sonic knows, is to tear it all down. Get away from the world that doesn’t enable him or destroy it. And if you’re the most important part of that world — literally its name! — then, by all means, destroy it anyway.