The Tamagotchi is Still Alive

A whole new generation of kids is cleaning up virtual poop

POG. Beanie Babies. Tickle Me Elmo. Tamagotchi. These are just some of the memorable toy fads that swept across vast swathes of the globe in recent decades. Of all the things that can drive millions of humans to sudden, collective, impulsive madness, I find toys among the most curious. I suspect it’s because I’m a product designer myself. There’s something intriguing about the idea that a team of people work on something for months (maybe more), unleash it on the world, and then see it flourish exponentially across the planet.

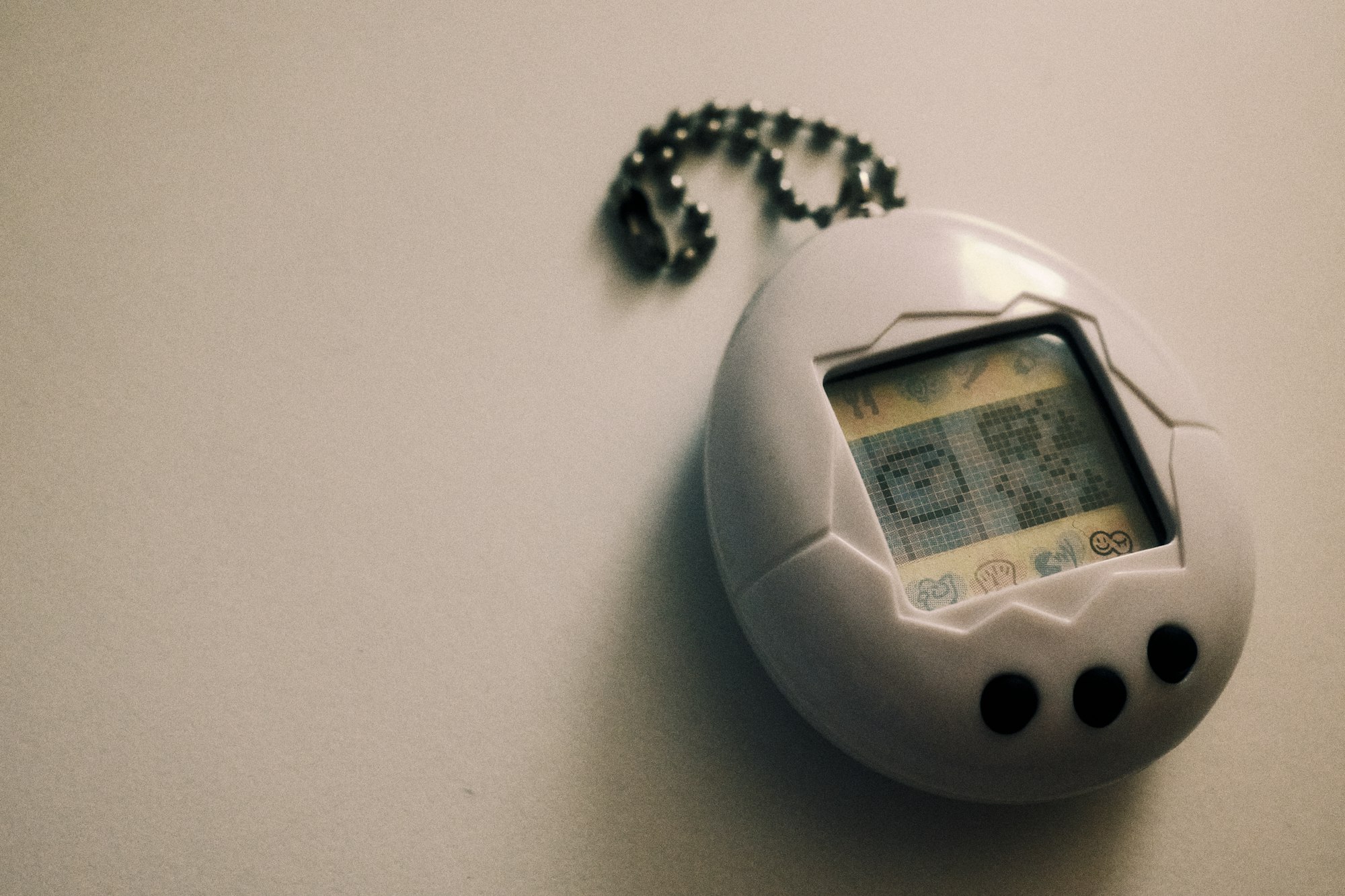

Tamagotchi is notable in my mind because of the way it so expertly fused a digital experience with a physical product. Given that this line of products took the world by storm in the late ’90s, there’s a good chance that at least some of you may not be intimately familiar with the phenomenon. So here’s a quick primer; I’ll be as brief as possible.

The Tamagotchi is basically a handheld digital pet, invented by Aki Maita and initially released in Japan in 1996 (debuting in 1997 around the rest of the world). Despite originally being marketed specifically to teenage girls, the product saw enormous appeal across a wide range of demographics — as of 2019, it’s sold more than 82 million units. Like any good toy fad, there were countless versions of Tamagotchi over the years — including all the expected licensing deals (there was even a Pac-Man Tamagotchi at one stage).

Despite being incredibly simple on a technological level (perhaps not too much more advanced than the high-end Game & Watch devices), Tamagotchi had some surprisingly deep functionality. As soon as you switched on the device, you’d be presented with a little wobbling egg, which would hatch into a creature — your new pet. From there, the parenting nightmare began. Your new family member relied on you for all of its basic needs: eating, entertainment, and health (if you left your creature’s poop unattended for too long, it would grow ill). Over time, Tamagotchi became more advanced. And, thankfully, a pause function was added.

This may be my most under-the-rock statement of 2020, but I had no idea Tamagotchi is still a thing. And I’m not sure how I feel about it. I’d say it’s generally accepted that Tamagotchi is the very definition of a fad product. Fads, by definition, exist in the zeitgeist for a finite period of time. So I’m honestly wondering who is still buying Tamagotchi today, especially in an era where smart phones are ubiquitous, and even the most basic mobile games are likely to offer substantially richer experiences.

Bandai and Wiz, the corporate marriage behind Tamagotchi, claim that this latest version is “the next generation of virtual pet”. There’s certainly a lot more on offer here than I remember from the original version. Of course, you’re still required to feed and clean up after your “Tama”. But now you can help it make friends, go shopping, travel, and — perhaps most bizarrely — your Tamagotchi can have its own “TamaPet”. Much like The Sims, your Tama can get married and have children, who will take on the traits of their parents. The games you can play with your Tama seem to be quite a bit more elaborate now. And in case you forgot we’re in 2020, your little egg now belongs to the internet of things, enabling you to connect with other Tamagotchi On devices to view other characters, play games, and even get married. There’s also some sort of smart phone app that interacts with the physical device, although I’m not sure how that works.

As far as I know, Bandai won’t release sales figures for Tamagotchi across any specific year (and certainly not from 2019, the year that the Tamagotchi On debuted). I am very curious to know how the latest version of the product has been received in an era where there are so many alternatives for kids to enjoy.

It’s not that the core appeal of the Tamagotchi has necessarily evaporated. I’m no expert on the subject, but it seems to me that the original product nailed a few important points. The fact that it was a digital gizmo must have been appealing to a generation of kids who had grown up on relatively modern video games. It was small (easy to throw in a backpack, or in your pocket, or hide from teachers in class), it required very little power (I remember it lasting for a very long time), and the wide range of colours and styles meant that there was a strong “collect ’em all” aspect to the experience. It probably helped, too, that Tamagotchi were relatively inexpensive — certainly cheaper than buying a Game Boy with several games. I can imagine that for some kids, Tamagotchi might have been an entry point into digital entertainment more generally. Also, let’s face it: when everyone at school is running around with their virtual pets, showing them off to each other, and discussing them…what kid is really prepared to be left out of that? The peer pressure to own one, especially for younger kids, must have been significant — even if they ended up throwing it in the drawer a month after buying it.

Obviously, Bandai felt that many of the same market drivers still exist today, and that a new Tamagotchi might be able to appeal to a new generation of kids. But evidently, we don’t know how the new model has sold, and the fact that a new Tamagotchi is a surprise to me suggests that it hasn’t exactly taken the world by storm a second time around. It’s tempting to lazily suggest that the ubiquity of smart phones is the single answer. It seems like an unsatisfying one though, given that various other toys that combine physical and digital experiences have been notably successful (an obvious example is the Skylanders toys-to-life series, which has sold well over 300 million units globally by now).

Maybe there are some Tamagotchi experts out there who can shed more light on this (and if you can, please do feel free to comment). In the meantime, I’ll continue to marvel at the re-emergence of a product I’d thought we had left in the ‘90s.