The State of Indie Games in 2024 and Beyond

Assessing both the current year and the future of the indie scene

Anyone who was conscious in 2023 could tell you that it was a massive year for video games. Powered by years of pandemic-induced development time and a lagoon of VC cash, companies put out tremendous game after tremendous game - and the world responded. Copies flew off the shelves, critics handed out some of the best reviews ever recorded, and everyone ended the year feeling confident.

And then, in 2024, everything stopped.

Major releases slowed to nonexistence, pulling down the whole market. High interest rates meant less money to go around for new projects. Most dramatically, with those tremendous games finished, companies announced thousands of layoffs. Plus, even with all of those sales, the industry - which had been in decline for two years - barely grew at all. With many A-tier developers holding back in anticipation of new hardware, it seemed like 2024 might be a very boring year.

Indie watchers, on the other hand, had a different take. It's no secret that small developers are at their strongest when large developers are at their weakest. With few significant A-tier releases on the horizon, it was games from smaller, upstart studios that were dominating conversations and wishlists at the start of the year. If 2023 was the year of huge prestige games, and 2025 set to be the year of new consoles and GTA 6, it seemed like 2024 could be a uniquely great year for small developers.

Did it actually turn out that way? Was this the year that David finally won the fight? Has the indie market grown as much as people thought, and how much of that growth went to the upstarts and bedroom developers versus established names?

As always, I didn't go alone. To better assess the behind-the-scenes details, I sent out a short survey to a range of developers who released games this past year. This year, I had more collaborators than ever, representing a wide range of genres and styles and everything from tiny developers all the way up to the people behind some of the year's biggest indies.

The following people responded:

- Alvios Games, developer of Vellum

- Brave Lamb Studio, developer of War Hospital

- Cicada Games, developer of Isles of Sea and Sky

- Cozy Cabin Studios, developer of Oh Deer

- Crazy Goat Games, developer of Republic of Pirates

- Daniel Carr, developer of Slider

- Deep Field Games, developer of Abiotic Factor

- Digital Sun, developer of Cataclismo

- Edym Pixels, developer of Grim Realms

- Eleventh Hour Games, developer of Last Epoch

- Fire Blade Software, developer of SENTRY

- FireTail, developer of The Faraway Land

- Guidelight Games, developer of SpellRogue

- HappyHead Games, developer of Spanky!

- Indirection Games, developer of Horticular

- Jonathan Coryn, developer of Player Non Player

- Kraken Studios, developer of Kingdom, Dungeon and Hero

- Thomas Moon Kang, developer of Duelists of Eden

- Tinymice Entertainment, developer of Stellar Settlers

- Tiny Trinket Games, developer of Zoria: Age of Shattering

- Torcado, developer of Windowkill

- Shatterproof Games, developer of Aarik and the Ruined Kingdom

- Singularity Six, developer of Palia

- Stumbling Cat, developer of Potions: A Curious Tale

- Sunset Visitor, developer of 1000xRESIST

- Unwound Games, developer of Echoes of the Plum Grove

- Whalestork Interactive, developer of The Night is Grey

- Wonderlust Games, developer of Infinite Mana

- Zarc Attack, developer of Exophobia

Source: YouTube.

To get an even broader perspective, I also distributed a shorter mini-survey to capture the opinions of current and aspiring developers still hoping to make it big. Between the mini-survey, full survey, and some short interviews with more established developers, I heard back from over 50 people and groups for this year's article.

And what did they have to say?

Overview: Are indie games on the rise?

The indie market opened 2024 with a track start. Anticipation was strong for Hades II, but there was also plenty of buzz for the likes of Manor Lords, Bodycam, and Black Myth, the latter holding the most followers of any game on Steam. Then Palworld dropped and proved to be a bona fide phenomenon, making a third of a billion dollars and dominating the most played games list for the first quarter of the year. This was followed by more huge successes with games like Enshrouded and Last Epoch and the announcements of sequels to indie heavy hitters like Slay the Spire, Wizard of Legend, and Hyper Light Drifter.

It was clearly a good year for some, and omitting some general weirdness (such as the mid-year avalanche of play-to-earn clickers), it was also a strong year for the games themselves. But did that translate into a good year for the typical developer?

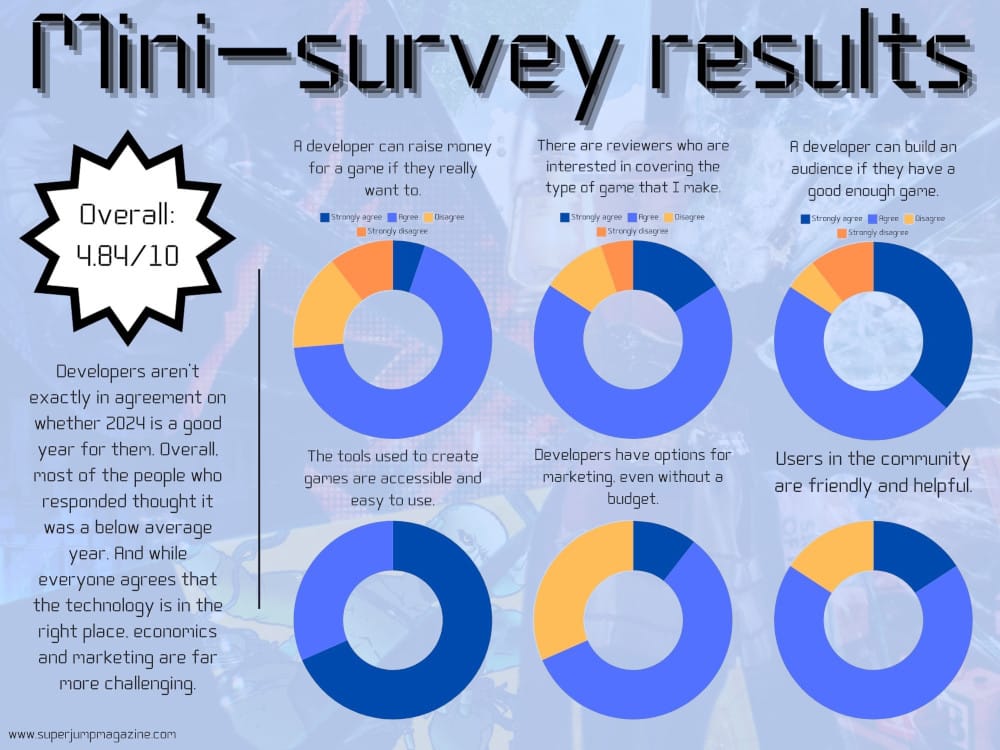

The people with whom I spoke weren't exactly in agreement on this. Respondents to the mini-survey gave a wide range of responses when I asked about their overall experiences, with the mean being slightly below average. The full survey returned similar results: A majority said that the market was good for the kind of games that they make, but a similar majority said that the market was overall bad and getting worse.

There is reason to lament the state of indie development. To get the perspective of a group that's been through the process, I spoke with Malavasi Freddi of Draw Me a Pixel, the group behind the 2020 metafiction hit There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension. "Competition has never been so fierce, and the recent financial failures of major groups like Embracer could reshuffle the deck in the near future," says Freddi. "We can imagine, for example, budgets being regularly revised downwards and/or projects being halted before their end. These conditions are likely to put smaller studios in a precarious situation, and lead to further studio closures in the 2024/2025 period."

"Competition has never been so fierce, and the recent financial failures of major groups like Embracer could reshuffle the deck in the near future."

Malavasi Freddi, Draw Me a Pixel

But no one starts a big project without at least some hope that it will succeed. Perhaps these oddly contradictory results are simply a product of developers being realistic while also anticipating better times.

Indeed, even many of those who don't necessarily see 2024 as the best year for indies do see things improving in years to come. "I am optimistic for the future, though," says Remy Siu of Sunset Visitor. "It seems like 2024 was a flagpole year for indies, where more and more people are realizing a huge % of their playtime is taken up by indies. That's exciting. Someone said to me they're hoping for an indie renaissance. I hope for that too, and I hope the players are there for it!"

For others, rough times can be an opportunity in their own right. "The following 2-3 years I expect to see a constant decrease of quality games being released, as many studios are closing/downsizing/focusing on existing IPs," says Stefan Nitescu of Tiny Trinket. "This will leave a lot of space for new IPs and new games to be visible, for those able to survive this period and find a way to preserve financial stability."

"Small developers should be fine, but I think there's a gigantic skill gap between the developers that are successful and the ones that aren't," says Duelists of Eden developer Thomas Moon Kang. "It also depends on how on-trend you are. If you have an idea that fits right in but is also unique, then you'll have a good time."

Certainly, the type of game makes a significant difference. What genres were the biggest winners?

Genres: What kinds of indie games do well?

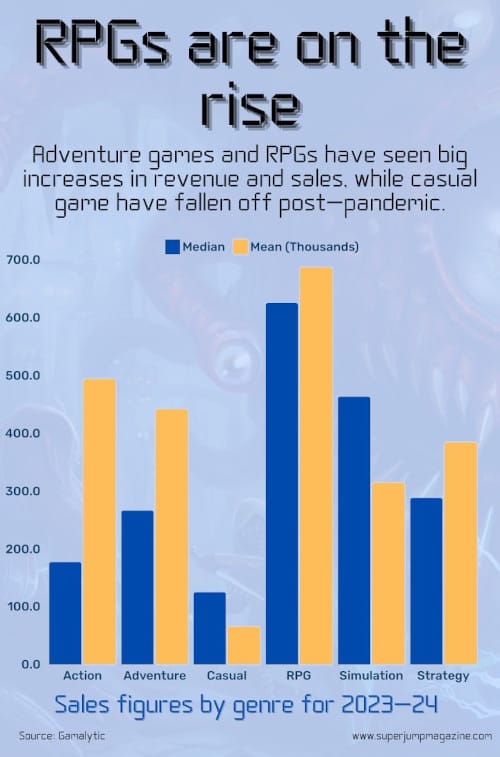

By the numbers, 2024 was looking to be a strong year for RPGs. With huge releases like Baldur's Gate 3, Hogwarts Legacy, and Starfield, RPGs dominated in 2023, and interest was high going forward. Likewise, action RPGs, a staple of A-tier console development, were still riding high. Meanwhile, interest in casual games has fallen off as pandemic-era gamers returned to their regular lives, while strategy games were looking risky due to the anticipated releases of new games in the mammoth Civilization and Europa Universalis series.

That's just numbers and theory, though. For small developers, the biggest genres aren't necessarily the best. ARPGs may be a big and growing market, but one doesn't idly decide to climb into the ring with a Tencent-backed beast, like Black Myth: Wukong.

"The biggest opportunities for small developers are always in pursuing interesting genres and underserved communities. Most AAA studios shut down their R&D projects over the last two years, so it is less risky and potentially more profitable than ever to pursue projects that focus on bringing something new to the table."

Renee Gittins, Stumbling Cat

There is a definite pattern to which genres work best for small developers. Those that comprise the core of the AAA world - FPS, action-adventure, action RPGs, strategy - can be difficult for small developers to tackle, chiefly because their games are inevitably compared to the A-tier competition. Small developers tend to have the best odds when working in genres that were either largely created by indies (deck-builders, open-world survival) or those that were abandoned by AAA companies long ago (city builders, JRPGs, traditional point-and-click adventure).

This has certainly been true for Gittins. "My most recent title, Potions: A Curious Tale, greatly benefited from the current interest in 'cozy' games and the lack of cozy-themed games with combat and exploration. It has fit well into an underserved market of women gamers who want adventure games that aesthetically appeal to them."

By contrast, getting into the fast-growing CRPG genre has been a tough move for Zoria developer Tiny Trinket. "The current RPG market is, based on our launch experience and what we have seen around us, quite terrible," says Nitescu. "The level of expectations has risen considerably in the RPG space, especially with the launch of Baldur's Gate 3. Together with the rising costs of development, it's pushing the budgets up a lot, quite a bit higher than the financing options available in the market today."

Of course, most developers aren't picking a genre based on market research, but on what they would like to see made, which is always a gamble. "I think the video game market nowadays doesn't look well upon restrictions," says Exophobia developer Jose Carlos Castanheira "Players want bigger, better-looking games that keep building on what they know from previous games. So while I thought having a clean and easy-to-pick-up game that respects players' time would be seen as a good thing in reality it was seen as something less valuable. I'm the kind of player that favors this kind of experience but the market doesn't think the same."

There are a few smaller developers who've succeeded in tough genres and scored big for it. Eleventh Hour is the group behind the hit action RPG Last Epoch and the most successful developer who responded to me. According to CEO Judd Cobler: "While there’s definitely a strong market for top-down loot-based ARPGs it’s a harder than average genre to break into because of the high complexity of systems, both player-facing and architecturally, and the intense competitive landscape."

New developer Unwound Games likewise found success in the notoriously top-heavy farm sim subgenre with Echoes of the Plum Grove. "We also knew that with Stardew Valley being such a huge hit, the expectation of other games achieving that level of quality was high as well," said Sarah Schaeffer. "I think in the end, we were happy with the game we made, and I definitely think Echoes has a place in the video game market."

The one thing worse than being in an overly competitive genre is having a game that doesn't fit comfortably into any genre. You might luck out and get a lot of press attention - as happened with last year's Chants of Sennaar - but games with ambiguous or overly broad genres have a nasty habit of underperforming. In a crowded market, people want to know at a glance if a new game is something they'll like.

Despite that risk, there's no question that flexibility with things like genre, mechanics, and aesthetics is one of the greatest strengths that small developers possess. "The biggest opportunity lies in niche markets and innovation," says Burak Tokak of Tinymice Entertainment. "Small developers can pivot and innovate more quickly than larger studios, allowing them to explore unique game mechanics and themes that may not be commercially viable for bigger companies."

If anything, the main trend in indie games isn't toward any specific conventional genre, but more toward mechanical elements and design principles that can be mixed and matched. There's also a sizable market in more niche genres targeting traditionally underserved groups. The "cozy" style, mentioned by many developers, is a good example.

"The growing popularity of cozy, community-driven games reflects a shift in player preferences towards more inclusive and relaxing experiences," says Javi Carlos of Singularity Six. "Players are increasingly seeking games that offer a sense of belonging and creativity, which aligns perfectly with the social simulation and cooperative elements that we’re pioneering with Palia."

"While we've never adhered to only one genre or visual style, our experience shows that there's no 'right kind of game' to make," says Israel Mallen of Digital Sun. "Yes, there might be trends going on and certain niches are more popular than others, but players value overall quality. If a game is carefully crafted and properly marketed, players will find out about it and likely love it."

While there have been winners and losers, there's plenty of room here for a lot of different types of games. But even if you do pick one of the winners and release your own game with perfect timing, other factors make things difficult.

Economics: Do indie games make money?

"I think that considering the current state of the industry, [being a] small developer is harder and harder due to global economics," says Michal Dziwniel of Brave Lamb. "After the pandemic period where game dev in general had been overhyped now we have to deliver not only the promise of good delivery, but good product delivery itself to gather interest and financials."

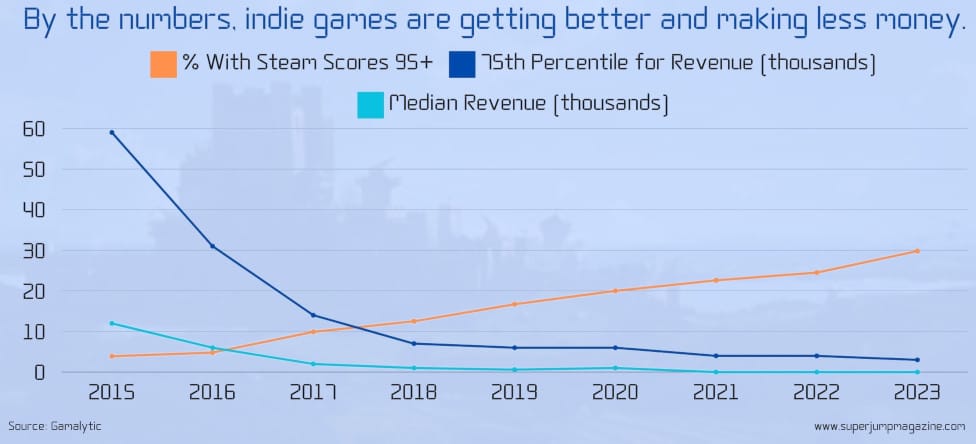

For any developer trying to make a living in video games, no issue looms larger than money. And while the industry has grown, it has - in the parlance of strategy games - grown tall rather than wide.

The concentration of the video game industry has been a major discussion point in recent years. Where enthusiasts once followed the hottest releases on a monthly or even weekly basis, a majority of sales, revenue, playtime, and attention now go to a tiny handful of games. This was very visible in 2023 when just 10 games were responsible for more than 60% of all PC market revenue.

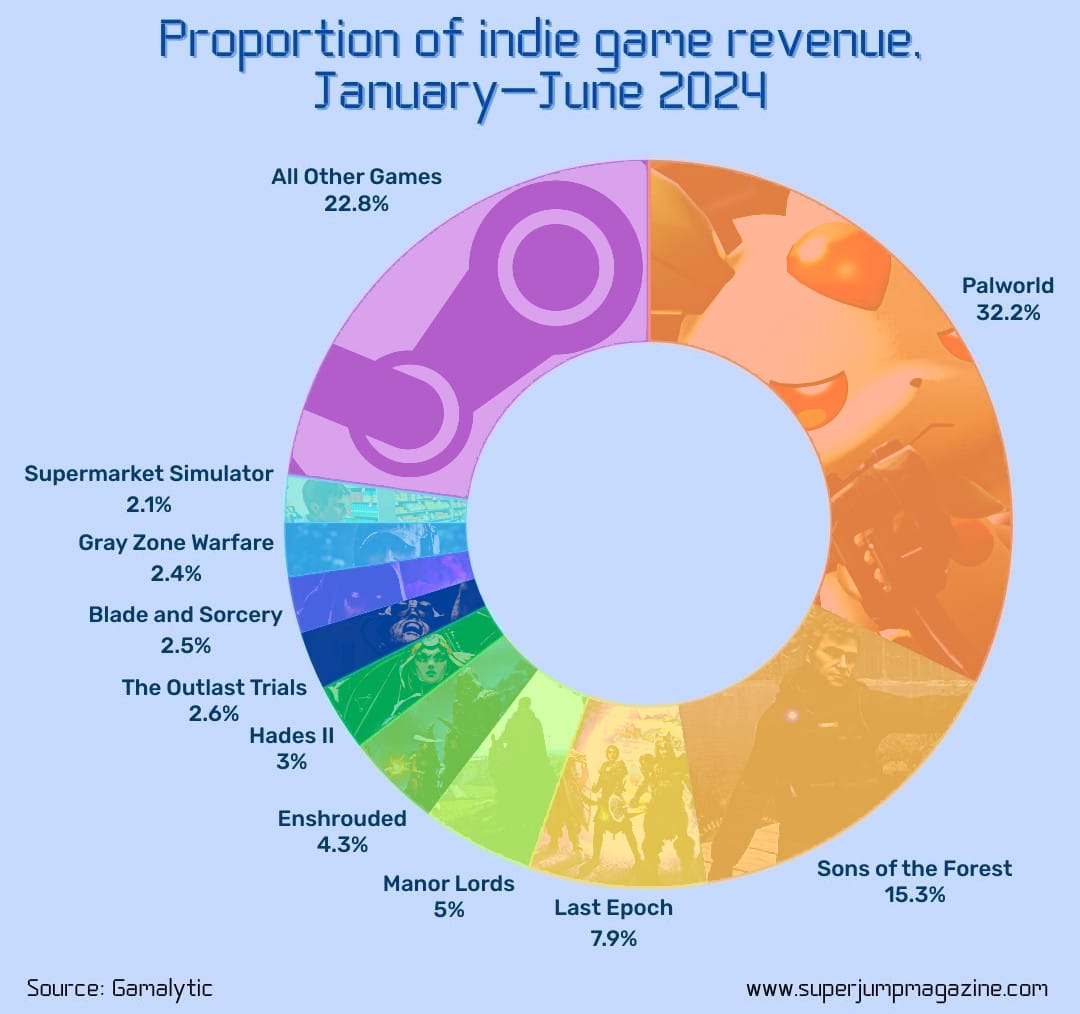

If anything, indies are more concentrated. For the first half of 2024, the top ten indie games generated more than three-quarters of all revenue, with just one - Palworld - drawing a third by itself.

"Yes, there might be trends going on and certain niches are more popular than others, but players value overall quality. If a game is carefully crafted and properly marketed, players will find out about it and

likely love it."

Israel Mallen, Digital Sun

The story really tells itself here. Video games, even (and especially) in the indie space, have become primarily hit-driven. While there are certain subgenres where one can build a steady following with a regular release schedule of smaller games, most developers are swinging for the fences with each attempt. Sadly, not every game has an equal shot at becoming a hit, and that game's genre may be the least of its woes.

The "hollowing of the video game industry" was a concept I first encountered in 2020 articles speculating on what the post-pandemic industry would look like. The notion was that mid-sized developers (including AA companies and some of the larger indies) would suffer the most. Small and solo developers would function more or less normally while AAA companies could survive on investment money while they spent more hours working on their big tentpole games. Mid-sized devs would get the worst of both worlds - high overhead with lower profile titles.

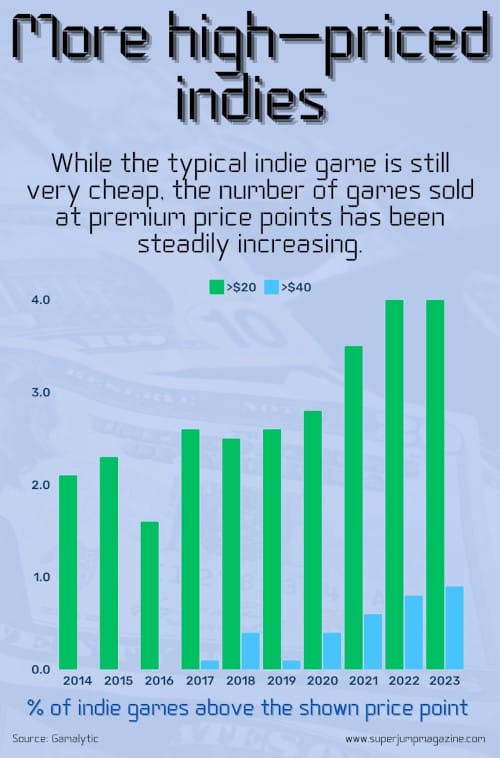

This time the analysts were exactly right, and if anything they undersold the issue. With production costs skyrocketing, the games themselves are being hollowed out as well. Increasingly, the most viable games are either massive titles with live service elements that can keep recouping money over time, or zero-budget games sold for a pittance in hopes of achieving meme status. Games in the middle - those with modest to high budgets - are struggling to make a profit.

It's easy to assume that these are issues of concern for A-tier companies alone. We do hear about major developers looking at rising costs and trying to balance the apparent need to raise prices versus the increasing desire of customers to pay less. Whether it affects indie developers depends on the specific developer's goal. For the true hobbyist who wants to make and release a game just to prove that he can do it, economics really doesn't matter. For others, it's an enduring headache.

"I feel indie developers are underpricing their games concerned about sales and setting a precedence for the player," says Alvaro Sousa of Kraken Studios. "Already I have encountered players thinking my game is worth half the price it is. They don’t understand the time and costs involved in making any game. They don’t understand the value they are given for the cost. A difference between a game costing $20 or $30 could mean whether the developer continues to make games or not."

Figuring out the ideal price for a game has become an art and a science in itself, with developers always seeking that fine balance between suspiciously cheap and bracingly expensive. A great example comes from marketer and publisher Michal Napora, who wrote about the decision to price the city builder Dystopika at $7 instead of $5 - a choice that made all the difference behind the scenes.

"I feel indie developers are underpricing their games concerned about sales and setting a precedence for the player. Already I have encountered players thinking my game is worth half the price it is. They don’t understand the time and costs involved in making any game."

Alvaro Sousa, Kraken Studios

This highlights the delicate game played by anyone trying to make a living in development. "Indie developers [will] certainly have a harder time going forward," says Sousa. "You have to wear a lot of hats. From what I read 80% of the field fails to create a livable income. 50% don’t even make $10,000. I was fortunate that I already wore many hats for development. I had enough money to hire out what I couldn’t do."

Of course, for many developers, having too much capital is not their problem. Getting any money at all has become a special struggle.

Financing: How do indie games get funded?

In March, documentarian Danny O'Dwyer of Noclip released a video concerning his own efforts to get funding for a small indie project.

The game was rejected numerous times, with publishers ghosting him and several offers getting abruptly withdrawn. Per O'Dwyer, the problem was that publishers were taking fewer games overall. Higher standards, more people seeking deals, less money in the market, and a pandemic-induced backup of existing games all added up to fewer opportunities for new entrants. And while that was for 2023, 2024 has actually been even worse.

Source: YouTube.

Investment money in the indie space has all but disappeared, even for proven developers. The gutting of Adult Swim Games and Humble Games proves that a famous name and a strong track record just aren't enough to stay alive. Venture capital, which was flooding into the video game space just a few years ago, has dried up as rising interest rates encourage firms to chase safer opportunities. And what money remains in play is being granted to ever fewer teams.

Developers are increasingly confronting this cash-poor future. "Small developers that are dependent on publisher funding are struggling and I believe they will continue to struggle," says Gittins. "High interest rates really discourage investment, and competition for the currently available funds is fierce and will only continue to climb as more professional developers start their own projects after being laid off."

How critical is investment, though? There's a fair bit of disagreement, and the numbers aren't clear.

GameDiscoverCo founder Simon Carless has consistently argued that funding doesn't matter at all. I've never been personally convinced - it's a case resting heavily on outlier titles and the arbitrary dismissal of certain games deemed "hobbyist" titles. However, there's a mathematical truth on his side: Every dollar that goes into a game's development has to be earned back, which is getting more difficult. To paraphrase Game Developer writer Michal Debek, success now requires small developers to invest more money and less money at the same time.

"Small developers that are dependent on publisher funding are struggling and I believe they will continue to struggle."

Renee Gittins, Stumbling Cat

This leads us back to the issue of the hollowed-out industry. With games getting less return on investment, the only viable choices for small developers are to either stick with extremely simple games or attempt to reach something resembling A-tier status - and the latter is a giant gamble in itself.

Ultimately, it may be a matter of finding a safe middle ground. "It's a balance that needs to be struck perfectly," says Rory Hulme of HappyHead, "between not spending enough time on your game resulting in a [immature] perception of your work but also not spending too much time on your game to the point where you see large diminishing returns. Even as a small team, it's tempting to chase perfection, but at the cost of another $100,000 it simply might not be worth it."

Oversaturation: Are there too many games?

The story of small developers is one of game discovery. For the third year in a row, market saturation and marketing were the biggest concerns raised.

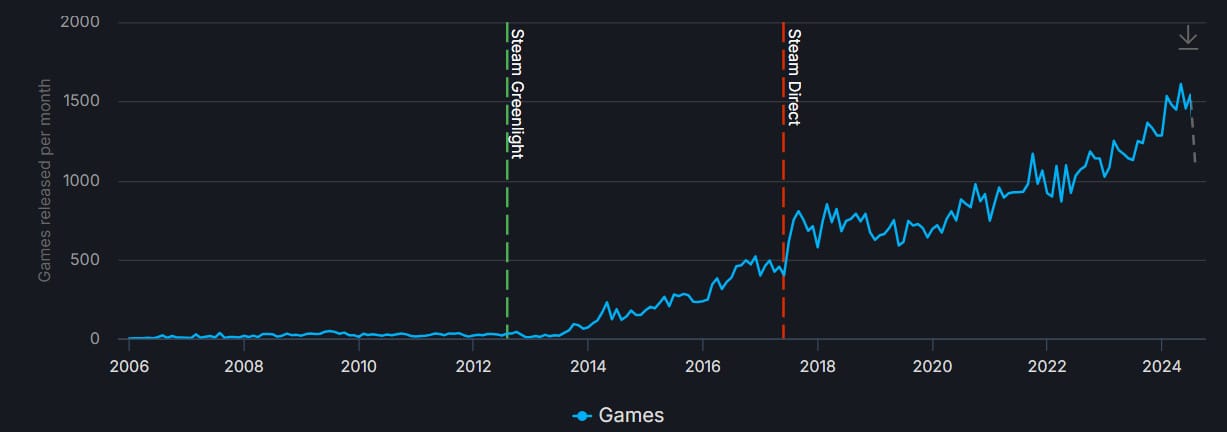

It's not like the problem has changed over that period, either. Steam, the primary platform for indie games, keeps breaking its own records for new games released. It can feel a bit repetitive to talk about how big Steam is getting, but it's just so consistently remarkable. They're currently on pace to hit 16,000 releases in 2024, about as many as were released in the entire decade after the introduction of the Steamworks API.

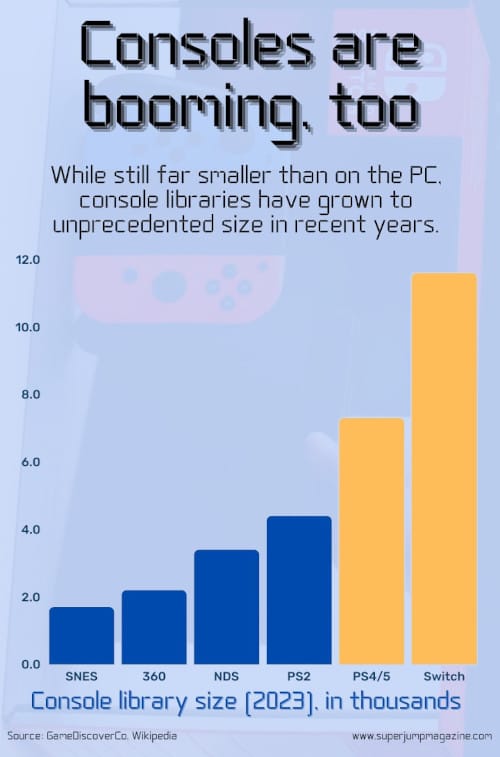

But let's not focus so much on Steam that we overlook the similar situation on other platforms. Over the course of this series, I've been surprised by how few of my survey subjects mention the consoles, which are supposed to be a promised land for indies. This year, only one person - Richard Kirk of Shatterproof Games - made reference to consoles, and that was just to suggest that the Switch would have been a good platform for his game had he released it a few years earlier. For almost everyone else, the PC is the known universe.

One reason for this omission might be that console libraries have also grown bloated. In this, the final year of the current generation, we can find out exactly how bloated they are and what this means for developers.

An analysis by GameDiscoverCo revealed that the most recent PlayStation consoles topped 7,000 games. That's half again more than what was available on the PS2, which previously had one of the largest game libraries among consoles. But even that is dwarfed by the Switch, which ended with a library of well over 11,000 titles.

Given the long-term availability of older games on digital platforms and the increasing availability of games across platforms in multiple generations (what Carless calls a "no-reset" environment), this problem isn't likely to turn around in the foreseeable future. Even if new releases fell to a fraction of what they are now, developers would still face competition from the 110,000+ Steam games that already exist.

But the bigger concern may be the existence of "forever games," a term referring to an aggregation of live service, competitive, and sandbox games that people play (often exclusively) over very long periods of time. Newzoo's PC and Console Gaming Report revealed that 80% of tracked play time in 2023 was spent on just 66 games, with the top five (four of which are over five years old) chewing up 30% of all play time. New releases and library sizes don't matter so much when so many people spend all their time with one or two games.

"I feel that the market isn’t favourable for any game at the moment," says Gary Burchell of Fire Blade Software. "The majority of the market is focused around a few big players, and there are a lot of developers competing for a smaller slice. When you add to that general content saturation that saps available time – whether that be from competing media, a plethora of free games, live service games, and a constant stream of new games – there’s no genre of game that isn’t affected by those conditions."

Discovery: How do people learn about indie games?

In an environment like this, getting noticed in the first place is the most important element of success and, for most, the hardest to consistently achieve.

For many small developers, video and streaming content creators remain the gold standard of indie promotion. On Reddit, developer Alex Voxel gave a behind-the-scenes report on what happened to his game after a content creator featured it on Twitch and YouTube. The effects, while small in absolute terms, were a major boost for a hobbyist developer, effectively doubling his visibility.

For other developers, content creators are falling short. Laying out his own experiences with promotion, a developer from Silver Eye Studios described what happened after sending out hundreds of keys for his new game. The results were dismal: A majority of creators who redeemed the key never did anything with it and the videos and streams that were made only converted into Steam wishlists at a 1% rate.

Put simply, for all but the biggest creators and/or the smallest games, this isn't enough. Insofar as it ever really existed, the age of the kingmaker influencer is coming to an end.

That's if you can even get them to pay attention, which isn't easy. "Before Covid, many content creators would gladly play a somewhat novel-looking game just for the content. It was great for indies, as there was real monetary value to it," says Jonathan Schenker of Alvios Games. "The content creators now realize how valuable they are (which is fair enough, they were undervalued before) and now small devs have to compete with much larger devs for the same few slots, and a lot of the smaller devs simply can’t afford that."

"Afford" may be literal here, as several developers suggested that being featured by a prominent content creator might not be free. Both Kirk and Freddi mentioned this, with Freddi saying "[T]his 'media success' can be difficult to initiate, as more and more influencers only agree to play in exchange for an advertising partnership, excluding smaller studios from the equation."

Even so, most developers need to maintain a good working relationship with content creators. "There are a lot of them, some with a large audience, that really just want to show some cool and new stuff and that can help you a lot," says a representative from Whalestork Interactive. "Some of the bigger, more cynical, news outlets will think you must have paid to get them to cover your game, but in reality, they are just passionate about new games and want to show them off."

But content creators aren't the end-all-be-all of discovery, and they may not even be as important as they were a few years ago. There is evidence that people are landing on new modes of discovery with shortform video fast becoming an important medium, especially in certain regions. For a younger audience in particular, it's likely that more and more people will learn about new indie games (and video games in general) through the likes of TikTok and YouTube Shorts in years to come.

A shift from streaming to short form wouldn't just impact marketing - it could also affect what types of games are made and which ones succeed. Roguelike games became so common at least in part because content creators prefer them. Having a single game that one can play for weeks or months on end makes for an easier creation schedule. However, success in short form means having a striking design, which could favor games with distinctive visuals and arcade-style mechanics that can be understood at a glance.

One game that has already benefitted from its stand-out visual design is Torcado's Windowkill. "It may be just confirmation bias with this single example, but for Windowkill I did basically no marketing," says Torcado. "I only put out a couple tweets and a Reddit post, and somehow the game gained traction on its own. Maybe something about it being eye-catching and easy to understand at a glance. But without those qualities, it's a lot harder."

There's also the issue of a game's digital footprint. Last year's Indie Bandits survey suggested developers were shifting away from major social media platforms. For most, this was due either to perceptions of their unreliability or for issues of personal morality or politics - all concerns that have only intensified since. Their respondents said they were putting more effort into their websites, though my own experience as a reviewer leads me to believe that Discord is becoming a new favorite platform, especially for the smallest developers.

But opportunities are different from game to game, and they can come from unexpected places. The Silver Eye developer who reported getting little benefit from content creators said that Reddit ads gave them the most bang for their buck.

All of which is to say that for the modern developer, there isn't one essential channel of discovery. It's whatever works best for them.

Tools: How are indie games made?

One area where developers are perfectly satisfied is in the underlying technology. Last year's Unity controversy doesn't seem to have shaken anyone's confidence in the tools of the trade. Marketing may be a confounding nightmare and money hard to come by, but the essential act of making a game is easier than it's ever been.

"I think small developers will have a bit of an easier time moving forward in the sense that many development tools are becoming far more accessible and documented, and there is an abundance of great courses and assets online to expedite the process," says Hulme.

Of course, accessibility can be a double-edged sword. Anything that lowers the technical barriers to entry is almost guaranteed to increase competition by multiplying the number of competitors. Developments that have made small teams viable - things like out-of-the-box engines, low code/no code solutions, and premade assets - are also a large part of the reason that so many games hit the market every year.

Currently, it is so-called artificial intelligence tools that are driving most of the conversation, and plenty of developers are already making use of them. The 2024 Unity Gaming Report found that 62% of developers are already using these tools, with that number likely to increase. This includes automation tools used to speed up routine tasks as well as the more controversial generative tools used for making assets.

It isn't entirely clear how many independent developers are among those using machine-generated content. The Unity report suggests that these tools are more commonly used on larger, more complex games than those favored by small developers. However, there's still a palpable fear of what the technology could do to the market.

This was a concern expressed by Whalestork: "[R]ight now, it only seems like it will get even more saturated with people using AI to accelerate stuff that not always has the best quality. It will get increasingly harder to find out games that are worth your time, so marketing will be more important than ever. The problem is that small creators can't compete in that segment. It'll be harder and harder to stand out."

There are steps that the marketplaces could take to stem the tide of machine-generated games, but Valve's history in this regard doesn't exactly inspire confidence. The continued appearance of asset-flipped games on Steam indicates that the screening process remains porous. And given the shockingly small team that Valve has working on Steam, this seems unlikely to change.

Audience: Is the indie community growing?

Whatever else might affect the success of a game, nothing matters more than the audience. As in every other creative endeavor, maintaining good relations with the fans has become a critical skill in the 21st century.

"Never underestimate the importance of post-launch support and community engagement," says Tokak. "The initial release is just the beginning of a game's life cycle. Ongoing updates, bug fixes, and community interaction can help maintain player interest and attract new players."

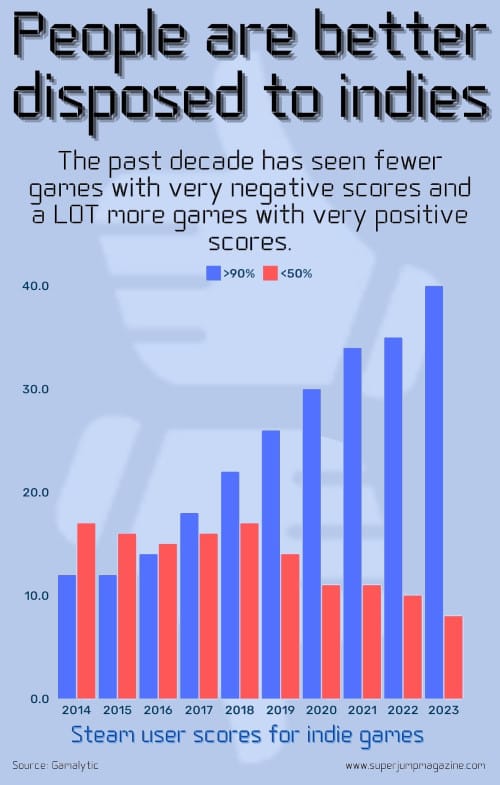

For video games in particular, the biggest trial here is increasing audience expectations. Dedicated indie fans no longer have the tolerance for bugs, design oversights, and rough gameplay that they did a decade ago - and neither do critics.

While 2023 was defined mainly by gigantic A-tier titles, there were still games from smaller studios in the mix. Slay the Princess, Cocoon, Pizza Tower, Sea of Stars, Turbo Overkill, Chants of Sennaar, and Jusant were among the smaller games with Metacritic scores of 85 or better. It's an interesting mix - long anticipated games from relatively established groups alongside out-of-the-blue newcomers; highly polished titles with strong production values as well as rougher games with DIY aesthetics.

Differences aside, the number of high-scoring games suggests that we are now in a world in which audiences and critics demand more from indie games. Many people now treat these games no differently than those in the A-tier, a view that offers greater prestige for developers, but also less room for mistakes.

"The only thing I think that is actually making things harder is the bar of quality is always growing," says Hulme. "As bigger companies are releasing things for free and focusing on in-game purchases, it creates a false sense of expectations in players who don't understand what work goes into games and why big companies can afford to release free games with microtransactions, while that's not necessarily viable for smaller teams."

"As the industry continues to grow with more and more games coming out, the expectation level will always continue to rise," says Schaeffer. "Though we are only a two-person team, the pressure to make sure we have enough content, no bugs, and everything being as accessible as possible will only continue to grow. You will always be up against AAA games with audiences or always compared to the quality standard of another game."

It isn't always easy to be a developer keeping consumers happy, but it's also not easy being a consumer. Market oversaturation impacts the audience too, with all of us wasting time and money on dubious games by disreputable developers. And that's before getting into all the outright fraud floating around. The massive recent spike in online scams has hit the video game community as hard as anyone else, encompassing everything from fake game keys and gift cards to malware attacks and account theft.

Thomas Moon Kang mentions dealing with scammers in his own community. "People have made fake websites of my games and lured unsuspecting users to download fake demos of my game in order to hack their discord accounts," says Kang. "In my discord server, there are constantly spammers and bad actors, and it all just makes an already overwhelming job where you wear so many hats even harder."

This is a problem that only keeps spreading. Rising expectations of games are a mixed blessing, but perhaps what we really need is higher expectations for platforms.

However, for all of these problems, that connection between developers and the audience is special, and it represents a potential source of strength in and of itself. "Players like buying games and supporting indie developers," says Siu. "I do hope games stay relatively simple this way, and I hope the players will keep this contract with the indie devs. We make interesting games and they pay us directly to have a digital copy. I hope that contract never gets broken."

Outlook: Are indie games the future?

Normally, this is where I'd make a series of predictions with greatly varying degrees of plausibility, but this year I'll only need one: The video game industry writ large is headed for an inevitable simplification.

It's no secret that the current state of affairs in the A-tier space is unsustainable. Costs are rising faster than revenue, and no one really knows how much more aggressive monetization people will put up with before they start jumping ship. But as you've seen, there's a similar problem at the bottom of the industry. Between the drop in capital, the consolidation of the market around a few games, and the less predictable return on developers' time and money, ambitious games are turning into an unwise risk.

Malavasi Freddi even brought up another, seldom discussed concept: "[S]ooner or later we're going to have to ask ourselves about the carbon footprint of video games, from their creation to their use by gamers. It's a very complicated subject, and I'm afraid I don't have the answers, but I do think that sooner or later we'll have to adapt in one way or another."

Any way you slice it, the era of massive games just can't last forever. It's an issue that looks different if you're a big company than a small team, but changes are bound to come either way.

Among the entities at the top, we're already seeing two approaches. One is to double down and keep making the games (and their monetization systems) ever larger. It's a risky strategy that's going to result in a few games that earn big and get a lot of praise and others that self-destruct and maybe take their developers with them.

The other approach is to go smaller and play to core strengths. For storied developers such as Capcom, Square Enix, and Konami, this means focusing on remakes and franchise titles that can be made on comparatively modest budgets and timeframes. For others such as Nexon, it means spinning off smaller teams to make games that can be profitably sold at indie prices.

But what about the actual indie developers? What does the road ahead look like for them?

There's a concept in economics known as the advantage of backwardness. The concept is that countries with smaller economies are well-positioned to take advantage of advancements created in larger, more developed countries. These smaller countries can avoid the problems that come with implementing technologies while also applying them in unique ways and taking advantage of their own innate strengths.

We may see something similar in video games in the not-too-distant future. Smaller teams already have advantages in terms of low overhead and less reliance on investment, but they're also in a position to learn from the tragedies and triumphs of larger companies. Freed from the expectations of photorealistic textures and giant sprawling worlds, they can focus on unusual aesthetics, innovative design, and bold narratives. In particular, small developers could be a perfect fit for a world built around remixable mechanics over well-defined genres.

"[W]ith an industry that has set up as its model of success games that are always bigger, always more expensive, always developed by bigger teams..." says Freddi. "Maybe the downsizing of video games will one day be a real subject, for which indie developers could already be 'prepared', with their small games, small budgets, and small teams."

"I think there is a rise of small games," says Siu. "We saw that happen a couple of years ago, but more games like EXIT 8 and Duck Detective are really proving a short game is good for the Steam Algorithm. I personally don't want Steam to turn into a bunch of small games, because I still love the indie game that tries to punch above its weight, but it seems like an opportunity."

It's not like I'm expecting this to happen quickly. We still live in a media environment dominated by a handful of mega-franchises that blot out the sun for everything else. Even so, those franchises can't last forever. Everything is eventually replaced by something else, and maybe we'll see a brand new class of games replacing the old guard. It's a distant dream, but one that seems at least possible.

2024 wasn't the banner year we thought it would be for indie games. All that means is that the best is yet to come.