The Rise and Fall of Aggressive Sincerity

Suspension of disbelief, audience participation, and the argument over writing quality in video games

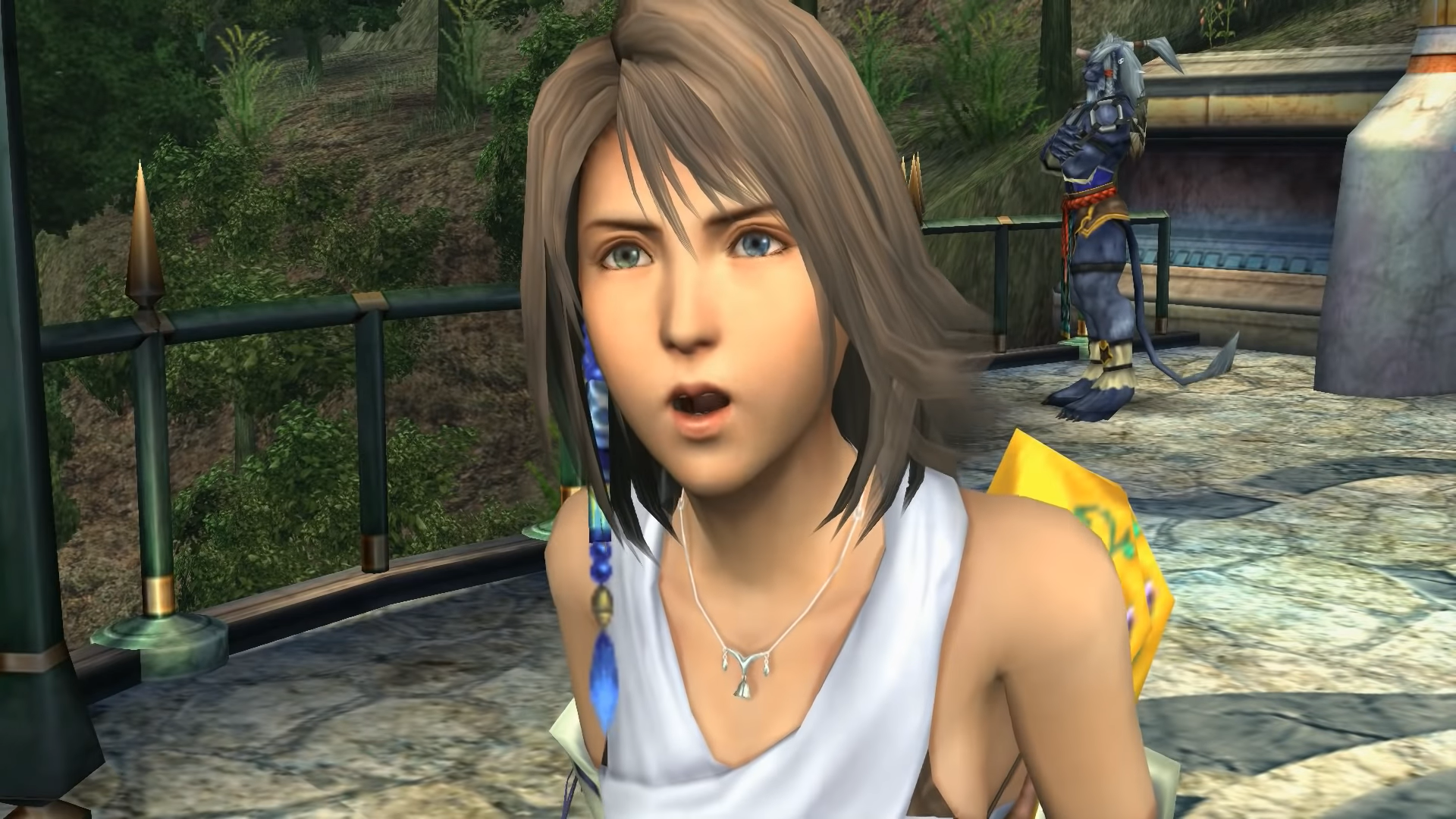

An infamous moment in video game history has been subject to equal parts praise and ridicule since its appearance. It has become a fixed moment of internet memeification; the arguments it has spawned have become legendary in their own right.

It's a moment between Tidus and Yuna in Final Fantasy X.

After defeating (or losing to) the Luca Goers and rescuing Yuna from an attempted kidnapping, there is a moment of levity between the protagonist and the deuteragonist. Yuna tells Tidus that summoners and their guardians are Spira's "ray of light." She confesses that she's learned to practice smiling when she's feeling sad and tells a forlorn Tidus that she knows how hard it is. He attempts to take Yuna's advice and laughs awkwardly and ridiculously as the camera pans over the remaining party, their faces in disbelief. All of them know something about Yuna's journey that Tidus doesn't—it profoundly colors the scene in repeat playthroughs.

Yuna eventually joins him and they laugh together. "I want my journey to be full of laughter," Yuna says.

In the twenty-plus years since Final Fantasy X's release, this scene has been referenced in and out of context in every conceivable fashion. Some have used it as a negative example of the game's voice acting, arguing that its quality is uneven and campy. Fans have argued in favor of the scene, defending its place and the sincerity of its characters. While it lends itself to being humorous and "cringe," the scene is an essential touchstone in Final Fantasy X's entire plot.

The Thorn Of Popular Convention

Discussions over writing quality have been rampant as of late. A recently released game has become the subject of arguments on writing quality, perception, context, and preference. Over the last few years, writing trends in popular media have changed quite a bit. What once was popular in nerd culture has altered considerably as more and more people have justified the existence of genre and its merits—characters no longer need to talk as they did in Buffy the Vampire Slayer in order to be effective or beloved. While twee writing has often been a core tenet of the "sound" of science-fiction and fantasy dialogue, audiences falling out of love with the quippy one-liners and idiosyncratic awkwardness of the Marvel Cinematic Universe have begun to see its long-lasting effects on media of all kinds. Characters are no longer speaking with sincerity or authenticity, instead punctuating moments of impact and melodrama with half-hearted attempts at lazy humor that ultimately don't carry any meaningful weight.

The 2022 film Everything, Everywhere, All At Once is a titanic example of popular metafiction mostly divorced from the superhero genre that still borrows heavily from nerd convention. It attempts to be a touchstone of geeky interests, packing subjects such as time travel, alternate universes, and superpowers into a grand package fastened by real human plights and lots of heart. Joy and her mother Evelyn share a real moment of tenderness and vulnerability near the end of the film, where outside of the many absurd universes they are together alone, momentarily speaking mother to daughter beneath the half-darkness of a poorly lit laundromat.

Spearing the moment's sincerity, Joy says: "Oh god, now I feel so awkward. This is awkward right?"

In a film that otherwise sidesteps twee dialogue and "Whedonesque" writing, it's as if its place in the popular genre makes it so the writers cannot help themselves. What should be the most endearing moment in the film's denouement is obliterated by Joy's lack of authenticity, reminding the audience that true tenderness and vulnerability are ultimately uninteresting. It undercuts the viewer (or player) from the experience, reminding us that this is all silly and meaningless.

Melodrama, Character, and Meaning

For years, RPGs have been on somewhat of an uptick in their seriousness. While games like Final Fantasy XIII were subject to some uneven tone and characterization in their writing, the RPG goes all-in on the subject of its melodrama. It does not pretend to be self-aware, or make its plot and characters secondary to a meta-understanding of the world it has built. For good or for ill, Final Fantasy XIII devotes itself to its subject matter, asking audiences to appreciate the plight of its characters. While Final Fantasy XIII is not the most beloved entry in the series (by a long shot), most criticisms leveled at the game have to do with pacing and less to do with the earnestness of the characters and their in-game experiences. Still, anyone unused to this particular type of writing might feel their fur being rubbed the wrong way as they try and wade through Star Wars prequel levels of dramatics.

In response to the wave of negativity surrounding Square-Enix's Forspoken, fans and detractors have attempted to wield the company's own sword against itself. Fans across social media have pointed at other scenes from popular Square-Enix games as an example of the "bad writing" that is par for the course in RPGs, citing Kingdom Hearts II or Final Fantasy XIV. There seems to be a generic misunderstanding among some audiences about the specific type of dialogue and writing that's being criticized with Forspoken—moments of dramatic and seemingly awkward sincerity have long been the staple of traditional JRPGs. One moment of recently scrutinized authenticity happens between Sora and Riku near the end of Kingdom Hearts II. "Well, there is one advantage to being me," Riku says with a smile in his voice. "Having you for a friend."

What defines the twee dialogue of the moment, and what drives it far beyond the pale of only being "quippy" one-liners, is how this sort of writing is often crafted by people who have a genuine disinterest in the genre they're peddling. Video games such as the Uncharted series have long been known for their quippy dialogue, but what differentiates Uncharted is the swashbuckling pointedness of the words. While Uncharted still occasionally commits the sin of "Well, THAT happened" framing, it is not flippantly or disingenuously breaking down the genre as a whole. It's goofy, and might not be enjoyed by every audience, but it is making some attempt at sincerity. When lampshading the artifice, it's important for the author (and game) to encourage the audience that they should be on board for the wackiness to come. Instead of baiting incredulity, a good video game can bring a player fully into the reality of the world regardless of the subject matter. Even if a plot point is considered stupid or beyond belief, it can land if it fits within the framing of the greater game. When genre cleverness is used as a way to hide the faults of a piece of fiction, the entire game can feel hollow.

Suspension of Disbelief, or Meeting Fiction Halfway

Recently, Austin Walker attempted to zero-in on the differences and unpalatable moments of Forspoken in his newsletter. Labeling this recent trend as "post-cringe" Walker discusses why the reactions to Forspoken have been so strong.

"But the thing is," says Walker. "When I sign up to go to the mystical world of Athia, ruled by four sorcerous Tantas and cursed by mysterious blight... I'm here for the artifice! I'm on board for ominous rhyming god-queens, and I'm not sure why Frey—for whom this is not artifice, and instead is her life, is not on board for it."

Suspension of disbelief exists as a term because, generally, audiences want to be fully involved in the fiction that arrests them. Audience participation exists in various forms but is a chief aspect of the very best stories. For decades the most absurdist anime has garnished love from its audiences by accepting itself as it is. What fashions an audience is their desire to care and believe—this is the difference between laughing with something, and laughing at it. While the beat-to-beat joviality of a Marvel movie might work in the temporary confines of a film, this trend of Hollywood scriptwriting is noticeably chafing when it comes from the mouth of a video game character.

All of this comes down to preference, writing style, and delivery. What works for some doesn't work for others, and what lands with one audience will miss hard with another. While video games such as Strangers of Paradise, Devil May Cry 5, or Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance permit their own fair share of ludicrousness, the limit of audience participation is right at the moment when they have to decide whether or not the thing they're engaging in cares about itself at all. Authenticity and sincerity are reflective in writing quality that's both good and bad, and we have unending examples of each. Video game goofiness has long existed, from Symphony of the Night's "What is a man?" speech to Resident Evil's "Jill sandwich" line, campy dialogue is often more memorable than it is awkward. But there is an incredible difference between authentic and synthetic sincerity.

The Changing of the Times

This all adds up to a personal appreciation of fiction. The frustration I experience is in the evolution, or lack thereof, of RPG storytelling. In a genre infamous for pushing the boundary of the medium by including sociological, philosophical, and religious themes, big studio RPGs have slowly become a victim of their own patterns, pastiches of stories mired in trope and convention. Year by year better writing is visible in smaller projects that don't demand the heavy-handed input of studios trying desperately to chase marketing trends. While Xenoblade 3 features the creative weirdness commonly associated with the genre, the actual quality of the writing feels decades divorced of Citizen Sleeper, Kentucky Route Zero, NORCO, Disco Elysium, and the like. Authoritative intent differs from project to project of course; last year's Triangle Strategy had a supremely poignant view of indentured service and genocide, and 2020's Yakuza: Like A Dragon showcased a thoughtfully adult story about male bonding and surviving homelessness in an ultra-capitalist society.

Trends change, and what works for the audience of one decade might not work for the audience of the next. But we need to remember that fiction is not materialist, and the "power of storytelling" is meaningless without a backbone of authenticity, humanism, and intent. While games like Kingdom Hearts or Yakuza might seem ludicrous on their face, it is how these stories and characters resonate with audiences that ultimately builds a long-lasting appreciation of the fiction. When engaging with any piece of fiction, I want to see evidence of sincerity so that I feel that my time is not being wasted. I am here for the weirdness, but maybe it's time for JRPGs to look outward and turn the corner by setting trends, not following them.

Over twenty years have passed by since Tidus and Yuna's infamous laughing scene reached audiences. While the argument over the scene's quality and necessity might rage on for another 20 years, Final Fantasy X would certainly be a lesser game without it. As tastes and preferences change, we never know what aspect of writing will be considered good, bad, or cringe.

"Even in the real world, actions taken by two people in a budding romance are generally embarrassing memories when you look back on them. I believe that this scene depicts that mental state very well. This scene of course is still made fun of by fans, but I imagine that it is because it greatly touched “something” in everyone’s heart for it to be such a memorable scene even after 18 years."

Yoshinori Kitase