The Man Behind Super Castlevania IV

A surprising tale that was almost lost to history

Video games are an integral part of my life. It’s not just that I have been playing games since a young age (the first console I actually owned was a NES, which my parents bought in 1988 — I was five years old at the time), it’s also that so much of my childhood — perhaps even my identity — is tethered to them. There are many reasons for this, but one stands above all others: my father. In many ways, my dad is one of the most admirable men I’ve ever known; throughout my life, I’ve seen him overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges that emerged from his own troubled childhood. Today, as an adult in my mid-thirties, I enjoy a close relationship with him — but as a child, this wasn’t the case. We weren’t close, spent little time together, and more often than not, he a figure to be feared; in a sense, he loomed over my childhood like a long shadow. How does this relate to video games? Well, games — especially Nintendo — were a kind of refuge where we spent time together, just the two of us. I remember that we obsessively played Super Mario Bros. and I’ll never forget my excitement when we finally reached the Special Zone in Super Mario World. But there was one game we battled with more than any other: Super Castlevania IV.

Perhaps it’s true of all children, but it absolutely never occurred to me that actual people made video games. I was certainly aware of Shigeru Miyamoto well before my teenage years (because, after all, he is something of a deity), but in general, it wasn’t something I considered. Today, of course, game creators are more visible than ever, as are the often shocking working conditions they toil under. Much of the conversation occurring today, as I write this, revolves around the obvious need for game developers to unite in some formalised fashion — perhaps in the form of unionisation. As questionable as working conditions for game creators may be in 2019, though, it’s worth sparing a thought for the game developers of the past — especially those working at Konami in the ’80s and ’90s. Back then, the people who worked on games weren’t credited with their real names. It turns out that the man who directed (and largely programmed) Super Castlevania IVwas credited under the name “Jun Furano”, but his actual name is Masahiro “Mitch” Ueno.

At least Ueno-san was able to choose his own pseudonym. It was based on a Japanese TV series called Kita no Kunikara, which took place in the cosy ski-village of Furano in the northern Hokkaido Prefecture. Jun was a major character in the series, which itself was about the Kuroita family and their struggle to adjust to a new life in the country (totally random side note: until recently there was a whole “museum” for the show in Furano — you could check out the various sets they used in the show). Learning about Masahiro Ueno as an adult was a pleasure in itself, but it also helped to re-contextualise my relationship with Super Castlevania IV. In some slightly tenuous way, it reminds me of the way your relationship with your own parents completely changes as an adult — it’s almost like you meet them again, with a new perspective, and although they are still your parents, they can also be great friends whose company you enjoy in a delightfully new way. I’ve never met Masahiro Ueno, but revisiting his life’s work as an adult is something of a revelation — in part because his time at Konami was remarkable, but also because his career since then reads like the ultimate bucket list for any aspiring game creator. Despite the rather enormous influence Ueno has had on video games as a medium, he remains humble, pragmatic, and still seems deeply curious and fascinated by the industry to which he contributed so greatly.

Akumajo Dracula

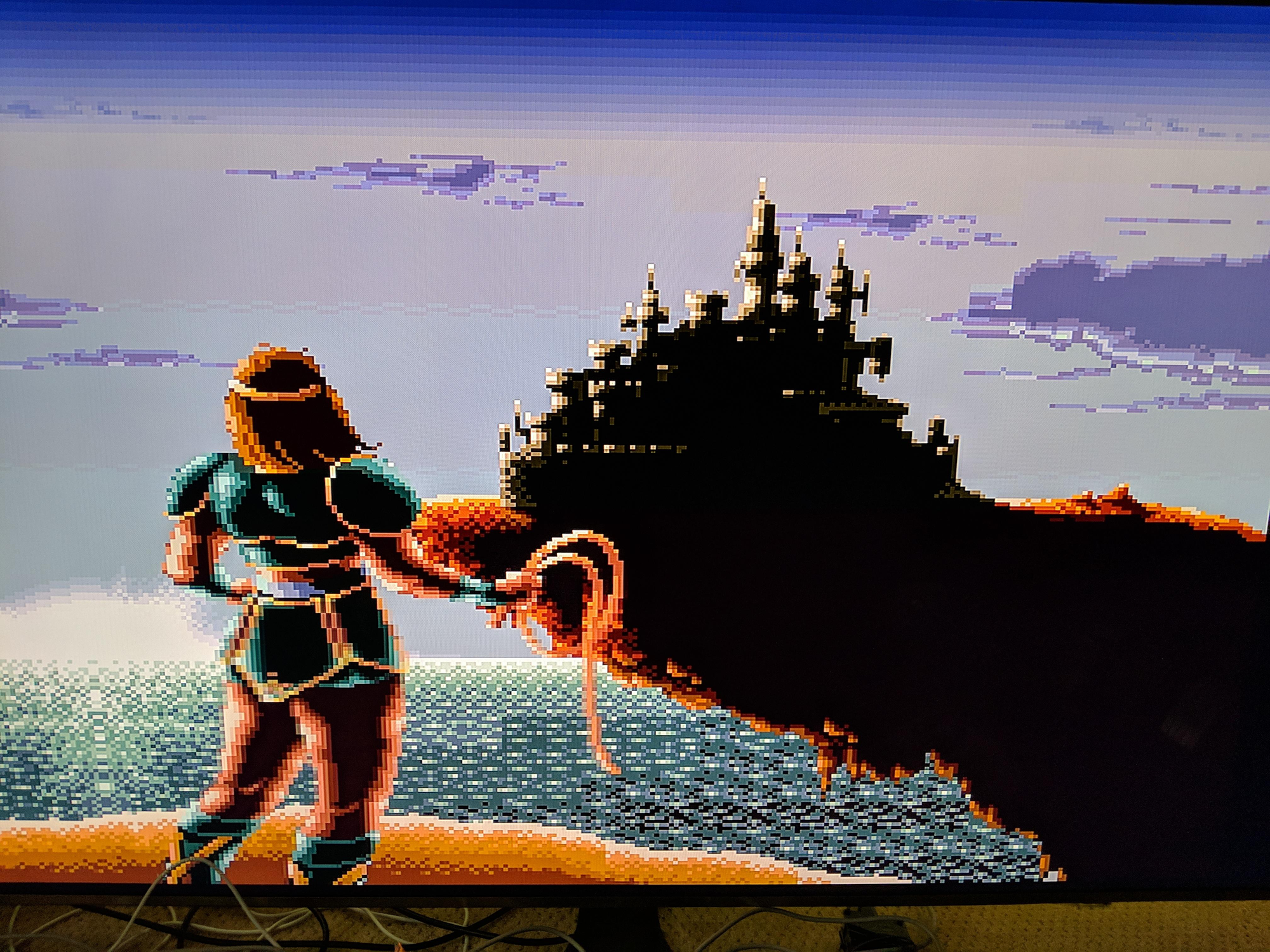

Super Castlevania IV is one of my favourite games. It is generally considered to be one of the best SNES titles, and it rivals Symphony of the Night for best overall Castlevania title (there’s a still-live debate among fans as to which game should take the crown; my favourite is definitely Super Castlevania IV, although I love Symphony of the Night and Rondo of Blood almost as much). Known as Akumajo Dracula in Japan, Super Castlevania IV is stunning in part because it still feels modern today. If you play it in the right setting (I’d recommend nothing less than the original cartridge played on Analogue’s Super Nt), you’ll experience something that feels like a modern action platformer with suitably-retro pixel art and production value so high it smashed through its Kickstarter goal many times over.

So much of what this game offers — especially when compared to its contemporaries — is a combination of seemingly microscopic attention to detail and a careful focus on what we’d now call user experience. These elements contributed to a game that I distinctly remember feeling genuinely “next gen” when it was new, and which still hold up shockingly well today. These observations aren’t just important in the context of other action platformers released in the late ‘80s/early ’90s, but they are also notable when viewed solely in the context of Castlevania games themselves.

Several Castlevania games had launched prior to the arrival of Super Castlevania IV, including three “main” titles released on the Famicom/NES. The second and third iterations of the main series represented fairly bold attempts to experiment with the formula laid down by the first game. And although Masahiro Ueno doesn’t remember exactly when development on Super Castlevania IV started, he has pointed out that it was developed in parallel with Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse. The two Konami teams who were furiously working away at both projects were actually collaborating with a shared audio team (who Ueno credits as being “the best” — when you listen to Super Castlevania IV’s audio design, you’ll find it difficult to disagree with that sentiment). Castlevania III was being developed by the “core team” — in other words, the group who had built the first two games. Super Castlevania IV was being engineered by a largely new team headed by Ueno. It was a small, highly cross-functional team. Ueno was the game’s director, but he was also responsible for programming the regular enemies and the bosses.

New Frontiers

More than anything else, I’ve always wanted to understand why Super Castlevania IV is so timeless — both forward-thinking and elegantly classical at the same time. I think the answer lies in the convergence of two important factors. One was the philosophy and approach that Ueno and his team took with the game, especially in terms of the major design goals they identified. The other was largely a timing question; both in terms of the game’s release relative to Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse and the debut of the SNES hardware itself. Let’s take these in order.

We know that both Castlevania III and Super Castlevania IV were developed largely in parallel, with much of the development taking place in 1989. This fact alone is important, because, as Ueno reflects, if Castlevania III had been completed before work started on Super Castlevania IV, it’s very likely that the latter would have followed the template laid out by the former. As it happened, Ueno and his team didn’t feel particularly constrained by what had come before. Having said that, the team were determined to make Super Castlevania IV an action-focused game without any RPG elements. If any of the previous titles were to inspire this new entry, it would actually be the original Castlevania (remembering that Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest was a significant departure from the first game, and featured a much larger RPG focus).

The development team was small, which resulted in a flat structure; ideas for the game’s design could come from anywhere, including programmers. And although they had established a basic blueprint for the game’s overall design, many of the final elements in the game were a result of continuous experimentation in the code itself (elements would be built, tested, and often completely re-built until they felt right).

Mitsuru Yaida handled the programming for the player character, Simon Belmont. If you’ve played the game, it’ll come as no surprise to you that a huge focus for Yaida-san was Simon’s whip — apparently, the team invested significant energy into its mechanics (and when playing the game today, I still adore the way you can make Simon stand in place and fling his whip around at all angles — the physical act of doing this is itself pleasurable). The developers were keen to craft an experience that “gave players more control” — the idea was to reduce player frustration. Ueno paid special attention to areas that players had found frustrating in previous entries (for example, in Super Castlevania IV, you can more easily jump on and off stairs, and you can attack in multiple directions thanks to the new whip mechanics).

Ueno and his team were perhaps under even more pressure than Castlevania III’sdevelopers; not only was Castlevania itself an established, high-profile franchise by the late ’80s, but Ueno’s group were working with the brand-new Super Famicom (SNES) hardware. Not only were the team attempting to finesse the Castlevania design to make it more intuitive, they were also determined to take full advantage of the new hardware and its impressive capabilities. This was no easy task, given that when development began, the team initially had no access to a SNES development kit — all they had were technical documents that gave them a sense of what the machine could handle. Ueno recalls that approaching SNES development was originally tougher and more complex than the Famicom/NES; it took time for the developers to experiment and understand exactly what was possible. Despite the technical complexities and learning curve involved, Ueno was clear about his vision for the game. Yes, he wanted to evolve the core gameplay design, but he also wanted to take the opportunity with powerful new hardware to create a far more atmospheric experience — something that would feel more “interactive and alive”. Fortunately, the graphics and sound capabilities of the SNES would provide a perfect basis for this.

Mode 7

The shiny new SNES hardware provided a broad canvas, within which Ueno’s vision could be effectively realised. But of all the tricks that his team used to craft a compelling atmosphere, the use of Mode 7 was definitely Ueno’s favourite. It was an effect that really made the game feel like a next generation experience — something wholly different than what had come before. Mode 7 was used for certain environments (perhaps the most notable case is a room where Simon hangs from a hook via his whip, as the entire building rotates around him — I remember being completely blown away when I saw this the first time). But the technique was used most liberally for boss characters, enabling them to feel larger than life — in some cases, they look like they might pop right out of the TV screen.

Just in case you are unfamiliar with Mode 7, it is essentially a technique where a single, two-dimensional textured layer can be scaled and rotated in various ways. Think of it like taking a large, flat tile and laying it down at an angle so that it appears to sit on the z-axis — although the picture is still rendered in two dimensions, the ability to scale and rotate this plane provides the illusion of depth in three dimensions. Several SNES games used the technique. Titles like Super Mario Kart and F-Zero used the large background tile to simulate a racetrack by rotating and scaling it around the player’s vehicle. This creates the impression that you’re driving or flying around a 3D space at high speed.

The Golem (ゴーレム) boss is an example that Ueno himself has cited as being one of the most impressive uses of visual effects in the game. There’s nothing especially demanding about this boss from a gameplay point of view, but the visual effects utilised here — especially the way the Golem shrinks as you break him apart through the battle — are remarkable, and were highly novel at the time. The ability to produce enormous sprites that could fill a screen — and which were beautifully articulated and textured — enabled Ueno’s team to convey a genuine sense of imposing danger. The new hardware enabled developers to essentially do anything they could imagine, and Super Castlevania IV used many hardware tricks to great effect.

Symphonies of the Night

As much as it is true that Masahiro Ueno understood the importance of leveraging the SNES’s hardware capabilities to deliver an immersive visual experience, he also recognised that sound and music could play a crucial role in rounding-out the game’s atmosphere. The combination of a peerless musical score and crisp, detailed sound effects contributed to an impressively chilling experience. It would be a stretch to suggest that Super Castlevania IV is scary by today’s standards, but upon its release, it was certainly pretty spooky.

Composed by Masanori Adachi and Taro Kudo, Super Castlevania IV’s score is not only stunning on its own terms, but it’s also utterly timeless. If you play the game today with some good speakers, I guarantee you’ll be floored by both the design and execution. Personally, I’d say that Super Castlevania IV boasts my all-time favourite video game soundtrack. And, in all honesty, I think it bests mostmodern game soundtracks, too.

Source: YouTube.

Although I like some tracks better than others, it’s not as though Super Castlevania IV’s audio isn’t superb throughout. Check out the above clip, recorded by Rodriguezjr Gaming on YouTube. This is the intro to the game. The moment you pop the cartridge in, Super Castlevania IV immediately presents an audiovisual tour de force. Deep, rumbling thunder claps punctuate a rhythmic, subtle bassline. The moment the headstone appears, draped in a sickly-low synth, your heart skips a beat. I actually found that moment creepy as a kid, and it still feels deliciously evil.

Source: YouTube.

Then, of course, you start the game and you’re confronted by the heart-pounding Theme of Simon Belmont. I’m listening to it as I type these words. It still sends shivers down my spine. The way the track meanders between quiet, almost contemplative beauty and outright shock-and-awe is magical. The music doesn’t just sound great, it also parallels Simon’s journey through Transylvania, as he nears the castle itself. I feel like this first track is all about getting you in the mood for a grand adventure — it’s brimming with a kind of celebratory determination; Simon is full of energy, ready to take on anything Dracula and his army of darkness can conjure.

I could write an entire piece just about the glorious soundtrack. It so effectively mirrors Simon’s adventure that you can almost listen to the music on its own and visualise where Simon might be at any given moment. Super Castlevania IV’s music was genius as a composition, but the fact that it so deftly exhibited the SNES’s high-fidelity audio capabilities makes it even more historically notable. At the very least, Konami managed to set a particular bar here that I honestly don’t think has been matched (let alone exceeded) very many times since.

Quiet Achiever

Konami’s early policy of not crediting staff with their real names had impacts that went well beyond the individual games they worked on. One consequence, I think, is that some of the most important people in the video game industry have gone largely unrecognised in terms of our broader consciousness. So, to come full-circle: we all know who Shigeru Miyamoto is. In fact, I’d argue that many people who have only a passing knowledge of video games probably know who he is, or have some general awareness of him as an important creative figure in the games industry. But there are so many creators — particularly those who played crucial roles in forming some of our most basic conceptions of what video games are today — who have largely gone ignored.

There are many fascinating things to be said about Masahiro “Mitch” Ueno; it’s not just that he is the principal creative force between one of my favourite games and, I believe, one of the best video games ever made. Ueno went on to build quite an incredible career in the industry. After Super Castlevania IV, Ueno went on to contribute to numerous other important projects — for example, he was the programmer for the NES version of Metal Gear (which was the version of the game that arguably popularised Hideo Kojima’s now-legendary franchise). Throughout the ’90s, Ueno took on an important leadership role within Konami, and he was tasked with establishing development teams in the United States. In the late ’90s and early ’00s, Ueno took on a more strategic role as Senior Vice President at Konami Computer Entertainment America, where he established teams that would produce titles for numerous consoles, including the Sega Dreamcast. In 2006, Ueno left Konami to work at Electronic Arts and since 2011 he has worked for multiple studios across a wide array of projects — including titles for mobile, and games that featured live-services models.

I mention all of this because I think Ueno’s career tells us something about him as a person. Even though I’ve never met him, I get the sense — through his interviews, and following his career — that he never simply rested on his laurels as one of Konami’s most legendary-but-unknown game directors. Rather, he remained humble over the years, and was clearly committed to life-long learning. That he left the comfort of home to work on projects that bear no resemblance at all to his early work, and that he fostered several generations of developers, is really a testament to a broad and deep contribution to video games.

As a biography of Masahiro Ueno, this article is is ultimately unsatisfying — there’s so much more to uncover, and I’d love to sit down and chat with Ueno about his life and career. Having acknowledged these limitations, though, I wanted to at least take some time to introduce him to you if you weren’t already familiar with this name. And I wanted an excuse to revisit a game that I love deeply, and that I will always remember fondly as an important part of my childhood.

Ueno-san, from the bottom of my heart, thank you.