The Joyful Design of Tinykin

A technical review of this delightful platformer using a game design framework

I wish there were more games like Tinykin. During the 8 hours of gameplay, it offered some of the most fun I've had with a platformer, in a way that not only seemed to evolve the formula here and there but to do so with a lot of attention to the craft.

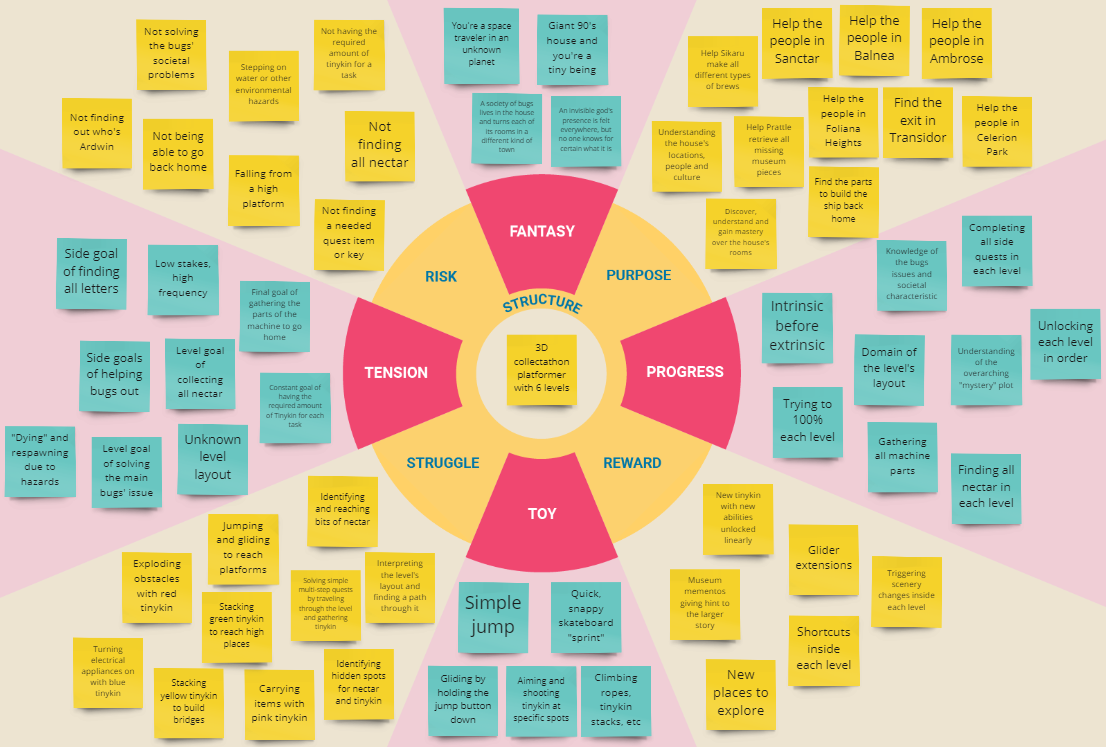

In order to organize my thoughts, as well as experiment with the model, I'm using my Colors of Game Design framework to do a technical analysis of the game's strengths and shortcomings. If you’re a game design enthusiast by any chance, hop aboard — otherwise, bear with me.

Structure: A classic collect-a-thon

Structurally speaking, Tinykin is a collect-a-thon in the vein of Banjo Kazooie, A Hat in Time, Unbox or Super Mario Odyssey.

You’re the tiny astronaut Milodane investigating your origins in a giant 1990s-era house, and your main goal is to retrieve the 5 parts of a contraption that will take you back home. To do so, you’ll need to help the insects living in the house with their big societal issues, as well as minor, personal chores.

The biggest misconception about the game — a justified one — is the parallel with Pikmin. Other than the army of tiny creatures following you around and the “retrieve all ship parts” motto, Tinykin doesn’t play at all like Nintendo's classic RTS.

Tinykin is all about exploring individual, verticalized 3D levels densely packed with objectives, collectibles, and whimsical places, using the titular creatures as abilities in order to get everything you need. Complete a major goal, and you unlock the next level. Do the side quests, and you unlock extras that will help you better navigate the house and understand the overarching story.

Tension: Find 'em, reach 'em, stash 'em all

Tension in Tinykin is of a low-stakes but high-frequency nature.

An invisible line reels you in at all times, prompting attention and action on a second-to-second basis. But the game never punishes you for not getting what you wanted, or not paying enough attention. The biggest risk in Tinykin is not finding an item and having to keep looking, or not being able to do something due to a temporary lack of tinykins.

Being a very vertical platformer, there's often the risk of falling from somewhere high and having to retrace your steps, but the game tends to avoid that by respawning Milodane close to the fall whenever the progress loss would be too harsh. That's also true for stepping in water and other deadly hazards.

The game keeps the collectibles lean: nectar and tinykin are the only currencies laying around, while other contextual pick-ups act as quest items that need to be found to complete secondary stories. This simplicity works wonders to help parse the information in levels, and the genre's traditional swathe of different collectibles isn't missed.

The player's struggle comes in the form of interpreting the level's geography and finding paths through it, identifying places where goodies might be hidden, and hoarding the amount of tinykin necessary for each job — exploding obstacles, building bridges, etc. There is no combat nor any actual puzzles, and hardcore platforming sections are kept to a minimum, but this delicate kind of tension is present every step of the way, keeping the game interesting at all times.

Toy: Glide, throw and... skate?

This is where Tinykin is at its best. Every action in the game is made to offer low tension and high response.

The closest reference here may be Super Mario Sunshine: there's a gliding mechanic to help the player adjust jumps and land in the right spot, and there's "shooting", albeit in a simplified manner. The player can aim and shoot tinykin at key spots in the scenery — to carry a vase, pick up a key, turn on a device, blow up rocks — but the crosshair always snaps on close points of interest, and throws the correct tinykin for each job, leaving to the player only the simple task of identifying an opportunity and aiming vaguely.

But the best (yet subtle) innovation, for me personally, is replacing the sprint button for a skateboard. Skating is super snappy and feels great, while the extra speed and reduced handling instill just the right amount of tension so it doesn’t turn into a no-brainer. Gone are boring stamina bars or the need to keep the button down during the entire journey. I've rarely, if ever, seen such a well-done balance of walking versus sprinting in any game. Plus, additional features of the skateboard, such as snapping to the edges of geometry and speeding through shortcut lines, leave plenty of space for the eventual speedrunner to perfect their paths.

To top it off, the audio-visual feedback for all this is superb. Throwing tinykin feels like snapping LEGO pieces into place, featuring a bar that fills with an increasing pitch to indicate how many you need. Exploding nectar-filled pastry plays a super satisfying "crunch" sound. Everything stretches and squashes as if it was a Nickelodeon animation, and interaction details like choosing to hold R2 instead of throwing the tinykin one by one are handled with lots of care.

The worst part of finishing Tinykin is that my hands were left wanting more.

Progress: Intrinsic before extrinsic

Tinykin is a game in which intrinsic motivation propels the player forward better than any promise of power, options, or trinkets. While the game has its share of all of these, they are not the focus and fall a bit on the short side.

It's understandable: the linearity and simplicity of rewards guarantee that the game flows swiftly in self-contained levels. You never need to go back to a level with a new set of abilities to unlock new areas (like in Donkey Kong 64 or in LEGO games), and every level can be beaten with 100% in the first pass.

The player's purpose is humble, but effective: finding all machine parts in order to go back home; helping out the bugs of the house in solving their problems and sorting out their differences; and uncovering the identity of Ardwin, the invisible-yet-omnipresent god of the house.

In between rooms, players are also encouraged to help Prattle, the museum curator, to retrieve all missing museum pieces; and Sikaru, the brewer, by finding every bit of nectar scattered throughout the house. Regardless of characters and story, players will also seek to discover, understand and gain mastery over each room of the house, and that’s perhaps where the main aspiration lies.

Actual rewards come in the form of new tinykin with new abilities, unlocked linearly as the story progresses; time extensions for the glider, so that Milodane can reach farther when platforming; and museum mementos that show potential but end up as unfocused and a bit dry.

But the best rewards, again, are the ones inherent to progression inside each level. New places to explore; shortcuts to travel through and traverse more efficiently; mastery over each level’s layout, and an overall sense of making everything work and tidying things up, all work to give players extreme satisfaction.

I’m being critical, but don’t get me wrong: go in without expecting intricate skill trees or Metroidvania power-ups, and the sense of progression and completeness will surprise you.

Fantasy: Cultist shieldbugs in a giant house, and something about aliens

Tinykin’s fantasy is also its main hook and where the game shows its seams.

The individual levels outline a romance of customs about an insect society divided into castes and waiting for the return of an invisible god. However, the overarching plot tries to tell a short story about creation, loss, and science that, despite its best intentions, doesn’t really land. It honestly feels a lot like a lack of time and resources to bring a great idea to fruition, combined with the chance of fleshing it out in an eventual sequel.

In the levels, dialogue is kept simple, as are the individual stories of the insects, but the rooms of the house are the real spectacle here. There’s the nightly Balnea, a bathroom-turned-city in which half of the town's inhabitants indulge in a perpetual pool party, while the other half dream of having, just once, a quiet night of sleep. There’s the kitchen turned Animal Farm and the greenhouse turned alchemist outpost. The kid’s bedroom holds an amusement park with a castle, a racetrack, and a field of asteroids while a giant dragon oversees it all. Every bit of the house is turned into some venue brimming with life and opportunity for exploration.

The fact that all characters are always facing the camera, including Milodane, helps set the stage and immerse the player in each level’s fantasy. This would be a hard sell in a bigger studio (been there), but it works so well that it leaves you wondering why we’ve all been looking at our protagonists’ butts for so many years without questioning it.

One thing that bothered me after a while, considering the lighthearted attempt at social critique, was the player’s frequent role of restoring the status quo, as in the tradition of old Disney films.

Party cleaners have boycotted the caste of sleazy, hedonist partygoers? Let’s make them forgive each other. Farmers are rebelling against the unscrupulous food hoarders? Milodane’s work is to make everyone make peace and restore things to how they were. What may pass as an attempt at political neutrality ends up as a call to put explored and explorers back in their places. It honestly sounds more like uncareful, design-by-committee storytelling than ill-meaning propaganda, but it leaves a bad aftertaste.

Conclusion

Tinykin is a joyful game through and through. While the story it tells and the one it wants to tell feel at odds with one another, the attention to detail in the setting and interactions really sell the sense of presence in this miniature world, delivering the universal fantasy of exploring a familiar place through an unfamiliar perspective.

It’s a game that keeps you interested not by a high challenge and the promise of conquests ahead — power, skills, choices — but more by how good it feels to play on a second-to-second basis, and how enticing the levels are to read and explore at your own pace.

All in all, it may please both the younger audience as well as the 30-something player whose hardcore demands happen from 9 to 5, and who may want to indulge in some carefree fun after that.