The Importance of Losing

Reflecting on the power of 'game over'

There are a lot of emotions that go into a Game Over screen. Maybe we’re frustrated — we’re mad that we lost or failed whatever task that got us to this screen. Maybe we’re apathetic because we know we’ll have to wait a while before we can get back into the action.

They get wrapped up in each other so tightly that it’s hard to pick them out, but we know the feeling of losing because it’s a near-universal constant across all genres of video games. Whether it be getting shot, hearing the quiet buzz of rejection in a puzzle game, or falling to your death in a platformer, it’s implicitly understood that with the possibility of success, there’s also a possibility of failure.

But what does it do for the player’s immersion and game experience? Losing possesses curious properties. It can both increase and decrease player immersion and shape a player’s opinion of the game as a whole. We want the positive aspects of losing — how it motivates us to play better and make us pay attention to the little details — without the negatives — getting frustrated or disengaged with the game. What are the boundaries of this perfect mixture, and how do games try to reach it?

Losing possesses curious properties. It can both increase and decrease player immersion and shape a player’s opinion of the game as a whole.

Why it can be great…

In terms of gameplay, the concept of losing presents real stakes for the player. We want to win because winning feels good, but we also want to avoid losing because losing feels bad. Whether it be losing your progress, some items, or even just having to wait to get back into the action, there are often negative repercussions associated with losing. How frustrating it feels depends on how hard the game punishes you.

Dying to something random in an RPG overworld only takes a couple of seconds to readjust, but dying at the end of a challenging boss with no checkpoints is enough to require a ten-minute break before coming back to try again. Similarly, dying in a more linear, narrative-focused game often means only losing a couple of minutes of progress, while losing in an RPG or adventure game means losing items, experience, and various other impermanent objects. The joy of winning is not just completing the objective or goal but avoiding the negative consequences of losing.

At first, it can look like a massive problem. Frustration disrupts immersion by bringing the player outside of the experience and, in most cases, is not a feeling the game intended to invoke. But small, harnessed doses of frustration can draw the player into the experience. Not just any frustration — it’s only useful when directed at the player’s performance.

Becoming frustrated at the game for its difficulty or poor handling cannot be remedied by anything other than taking a break or turning down the difficulty, both of which aren’t particularly good for immersion. But when the player becomes frustrated with themselves, performing better by focusing more both makes them more likely to succeed and more immersed. Positive frustration encourages us to pick up the controller and go at it again, along with making the reward so much sweeter when we get it.

Certain games specialize in harnessing frustration. From rogue-likes that feature losing as a central mechanic to just plain difficult games, getting frustrated is an essential part of the experience. Gamers attracted to these kinds of challenges seek them out with the knowledge that they’ll be frustrated but will enjoy it all the better in the end as a result.

Frustration is also why difficulty levels are practically an industry standard to make the game enjoyable for as many people as possible. Incorrect levels of intended frustration, whether too high or too low, can make the game unenjoyable through boredom or anger. Hardcore and casual players can feel the same amount of satisfaction when finishing a game if their difficulties are matched appropriately. As a mechanic synonymous with challenge, losing is a unique tool available to video games to create immersion.

Certain games specialize in harnessing frustration.

And why it can be awful

But in other areas of immersion, particularly narrative, losing presents several problems. Technical issues become immediately apparent — the player must physically wait for the game to restart, a break from the action they were focused on, and the visual and auditory environment in which they were immersed.

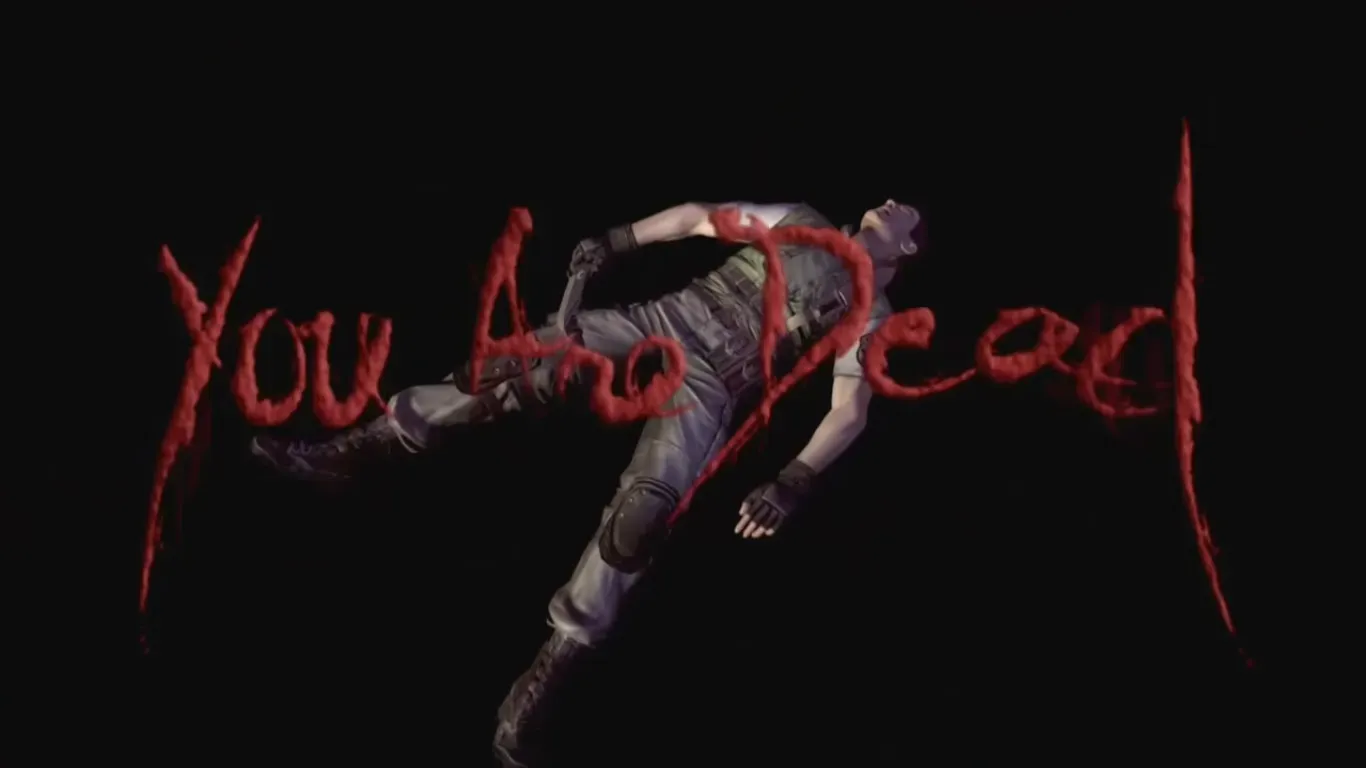

Constant repetition of voice lines, cutscenes, and other assets is also a valid concern, as moments that might have been engaging the first time around become grating and annoying the third or fourth. For highly-scripted moments like boss-fights, which rely on a well-defined sequence of moments to be emotionally effective, losing and then playing through everything again can kill any mood or atmosphere.

The issue is much larger than general repetition though. When a game is happy to let your character ragdoll whenever they die or cut to black and then show a quick gameplay tip before respawning you at a checkpoint, it leads to an uncomfortable reminder that the game is still a game. They have as many tries and as long as they want to get the action just right, and the game will gently put them back to where they should be every time.

Imagine if a movie paused in the middle and asked the viewers if they feel comfortable in their seats, or if a book reminded you to keep reading. Good media immerses us by making us look past the strangeness of staring at stacks of inked paper or sitting in a dark room with strangers and focusing entirely on the narrative or experience at hand. Death reminds the player of their fundamental disconnection from the media they’re experiencing, which, in most cases, is an undesirable effect.

Games designed around constant failures, such as rogue-likes, work some immortality or time-loop into their narrative to explain the repeated sequences. But for more linear and realistic games, death is often a massive point of dissonance. Sitting through something already experienced not only reminds you of the distance between you and the media but is just plain boring.

This issue only gets amplified when considering the ludological implication of losing as well. Not only will we get pulled out of the experience, but the frustration we have towards the gameplay consumes our attention. The same thing that drives up the challenge and intensity of the action for the player can also make them forget or ignore the context behind that action.

Death reminds the player of their fundamental disconnection from the media they’re experiencing, which, in most cases, is an undesirable effect.

Finding balance

Conflict in media draws people in because of uncertainty. We don’t know what will happen if characters act or interact with their environment the way they do, so we stick around to find out. If we know what will happen — how we beat the boss, the path we take to get there, and who we might meet or lose along the way — then the mystery is gone. Death or losing is a necessary potential option that the game can lead to for conflict to be possible or realistic.

If we know we will succeed every time or face no consequences for failing, there is much less suspense involved in those tense narrative or gameplay moments. The only excitement or joy we can derive from the game is the joy of simply playing or existing in its world. There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with that — plenty of games are enjoyable without death or loss, and some even benefit from it. But for a similarly large amount of games, they’re helpful tools for adding immersion. Losing is like a seasoning that brings out the flavour of the main dish — when done just right, it accents the highs of the experience, but when done wrong, it can overpower the rest of the game or not be present at all.

The invisible hand of this concept is found and considered everywhere. We invented checkpoints to avoid constant repetition, and they’re now a fundamental feature in games across all genres. In certain moments of high intensity or excitement, like a chase sequence, some games remove the possibility of losing entirely, sacrificing a little bit of realism and continuity with the rest of the game in favour of keeping the hype and momentum up.

In other moments where the narrative takes to the backseat for a bit, games might amp up the difficulty to push or frustrate the player and get them more engaged in the gameplay. It is, like all things, a unique tool applied according to artistic intent.

When games are careful about how they use and apply it, they can turn a Game Over screen from a moment of frustration into a powerful motivating force.