The History of Australian Games Classification and Censorship

The long, often frustrating story of game classification in Australia

Ever since video games hit mainstream audiences, they have struggled to be seen as something more than toys for children. Even as the video game industry has grown to be a multibillion-dollar juggernaut, there are still parents, politicians, and right-wing pundits looking at games series such as Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty and saying ‘won’t somebody think of the children.’ But entries in the GTA and CoD franchises, amongst many other popular games, always have clearly displayed on their boxes or sales pages the local equivalent of the mature or adults-only classification.

Since their introduction in the early 1990s, these classification systems have been a way of legitimising games as a pastime for adults to the wider public, while also showing how various parts of the world are still looking down on video games and making broad assumptions about those who play them.

I live in Australia, and my country’s classification body, the Australian Classification Board (ACB) has a habit of making international news in gaming circles for banning games that have not seen issues with classification elsewhere. As an international reader, you might have noticed when Fallout 3 was banned in 2008, Saints Row IV in 2013, or Disco Elysium last year. There are many examples from the introduction of age ratings for video games in 1994 till now that prove that Australia has one of the most strict games rating boards in the western world.

I’m going to take you through the entire timeline of games classification and age ratings in Australia, and the major cases of games that have run afoul of the board, so I can provide some clarity to the question many have – why is Australia, a country not known for censoring pieces of media, so tough on games? And how do so many game publishers and developers still find themselves getting hit with a surprise ban?

It all started with a pair of games that were causing controversy and congressional hearings in the US.

Video game violence controversy reaches Australia

Over the course of 1992 and 1993, the number of voices decrying the level of violence in video games grew to a point where governments got involved in the issue. In the United States, there were two congressional hearings on the subject of violence in December 1993 and March 1994. As a result of these hearings, the ESRB (Entertainment Software Rating Board) was formed to give age ratings to games and has been in use ever since. Three games took the focus of these hearings, two of which are hugely influential classics that pushed the boundaries of virtual gore. Mortal Kombat, whose 1992 arcade release introduced realistic-looking sprites and gruesome fatalities to millions of players, and Doom, a huge hit on PC which came close to matching MK with its gore and was released after the first hearing. The third game was the one that was singled out when the controversy surrounding violent video games hit Australia in 1993. While it did not appear to be anywhere near as violent, and certainly nowhere near as popular, as the other two games, it nevertheless takes its place in the gaming pantheon as one of the titles that caused age ratings to come to video games: Sega's infamous Night Trap.

Night Trap: Sadistic and misogynistic or campy and tame?

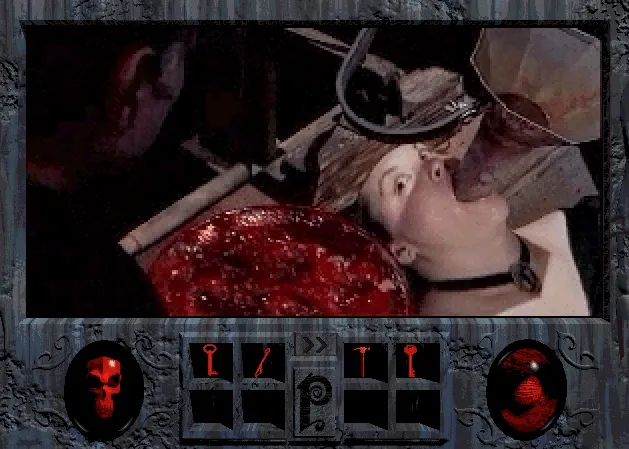

Night Trap is a 1992 game that originally appeared on the Sega CD, a CD-ROM add-on for the Sega Mega Drive (called Sega Genesis in the US). It utilises the CD format to incorporate FMV (full motion video) sequences into the game. In Night Trap, you are a part of a surveillance team that is watching over a house full of teenage girls having a sleepover, who are unaware of the fact that vampiric beings called Augurs have invaded the dwelling. You have to set and deploy traps to prevent the girls from getting captured. Like many FMV games of the time, Night Trap is very cheesy, very campy, and quite limited in its gameplay. What is more notable is what it isn't – it is not particularly violent, nor is it sexually explicit. Sure, the teens, portrayed by actors in their 20s, are mostly in their undergarments, but it’s hardly racy, and it is basically bloodless, despite starring vampires. Instead, when you fail to trap the augers, they use this weird contraption that looks like a dog collar on a stick with a drill-like thing attached. Below is the most infamous scene of Night Trap, which was specifically brought up in the congressional hearings and by Australian politicians.

Source: YouTube.

As you can see, the death scenes in Night Trap are quite tame, certainly not on the level of Sub-Zero ripping out someone’s spine. Certainly not the torturing and mutilation of women that it was described as being, and it should be said, not a reward for the player either, as these were frequently described as being. They were game-over sequences, as the violence wasn’t the goal (as was often stated) but what you were trying to avoid. Regardless, Night Trap became the main point of contention in which the discussion of age ratings for video games in Australia filtered through.

Age ratings for video games arrive in Australia

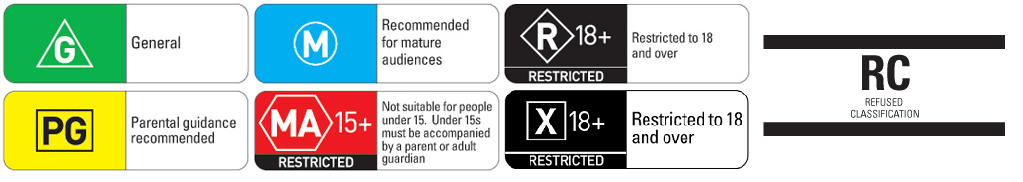

With the passing of the Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) Bill 1994, video games became subject to the ACB, which was then a part of the Office of Film and Literature Classification (OFLC), and its rating system. Around the same time, video game classification was introduced, with a new rating added to film classification. The newly expanded age rating system, which is the same now as it was back then, is as thus:

- G: General audiences

- PG: Parental guidance recommended for under 15

- M: Recommended for people aged 15 years and over

- MA 15+: Restricted to people aged 15 and over (added in 1993)

- R 18+: Restricted to people aged 18 and over

- X 18+: Reserved for pornographic films

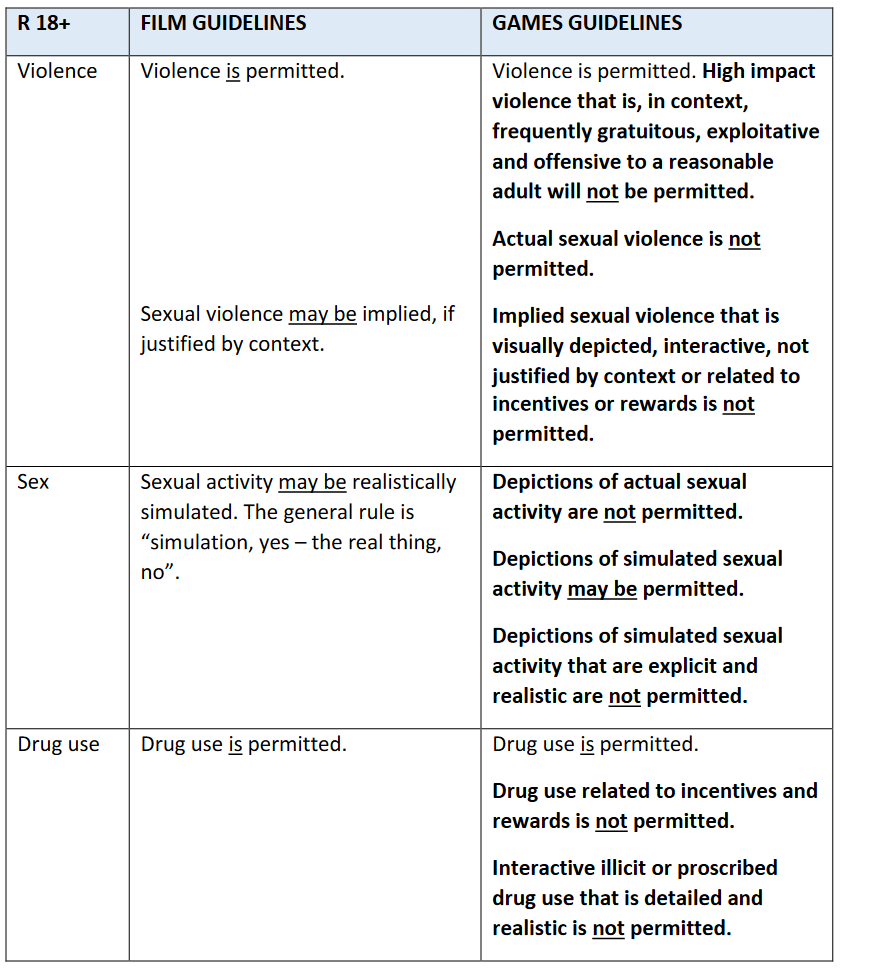

There were a couple of key differences in the ratings of games. One was minor – PG was briefly replaced by G 8+, which lasted until 1996. The other had far-reaching consequences – the ratings stopped at MA 15+. If the content was deemed to be too much for the MA rating, it was refused classification (also referred to as an RC). The original reasons for a game receiving an RC are as follows:

- Depictions of realistic violence, even if not detailed, relished, or cruel, extreme horror scenarios or special effects, unduly relished acts of extreme violence or cruelty.

- Nudity including genitalia unless there is a bona fide purpose, simulated or explicit depictions of sexual acts between consenting adults, any depiction of sexual violence or sexual activity involving non-consent of any kind, depictions of child sexual abuse, bestiality, sexual acts accompanied by offensive fetishes, or exploitative incest fantasies.

- Use of sexually explicit language.

- Detailed instruction or encouragement in matters of crime or violence, the abuse of prescribed drugs, depictions which encourage the use of tobacco or alcohol, or which depict drug abuse, depictions which are likely to endorse or promote ethnic, racial, or religious hatred. (Source).

As you can see, these boundaries are far stricter than what is placed on films. For those outside of Australia, it’s worth a quick comparison. For films, the M rating is more permissive than the equivalent US rating, PG-13. If you say the f-word more than once, you can show nudity, sex, and drug use, provided they aren’t explicit. A lot of M-rated movies would be facing bans if they were games with the same content.

The first ratings (and the first bans)

In April 1994, Mortal Kombat was the first game to be subject to the ACB’s age rating system. It received an MA 15+ for high-level animated violence. In an ironic twist, Night Trap not only passed classification but was rated only an M for medium-level violence. Doom, too, passed with an MA.

In February 1995, the first pair of games to be refused classification were cyberpunk adventure game DreamWeb and FMV thriller Voyeur. DreamWeb is a cyberpunk adventure game, which contained a sex scene that was interrupted by the player, who is there to shoot and kill the exposed man in the room. This was enough to count as sexual violence (a very liberal interpretation, to say the least), and the game was slapped with an RC. A version with the offending scene cut was submitted and received an M. Voyeur is an FMV thriller that received an RC due to running afoul of the ‘use of sexually explicit language’ rule. There is a scene that refers to a character being sexually abused by her uncle.

The scene from DreamWeb that led to the first RC. Source: YouTube.

Shortly afterward, two more games received RCs. First was Roberta Williams’ Phantasmagoria, the high-profile FMV horror adventure from Sierra On-Line, which was also drawing controversy in the US due to its gore and sexual violence. In 1997, the compilation game Roberta Williams Anthology, which contained the first chapter of Phantasmagoria, also received an RC. The game has never been reclassified, but was released on Steam and GOG in 2010. The second is a game called Strip Poker, which was given an RC for fairly obvious reasons. In fact, most of the games that received an RC in the '90s were such as this – budget games leaning into, or going all the way to, softcore porn territory.

Pre-censoring and early attempts to evade the ACB

It seems that the ACB’s reputation for being harsh on games became apparent quite quickly, as there were several unorthodox attempts at avoiding the dreaded RC in the 90s. A couple of notable violent shooters had pre-censored versions submitted to the ACB with mixed results.

Duke Nukem 3D’s Australian version had the women in the game – the scantily-clad waitresses, strippers, and cocooned prisoners asking to be put out of their misery – removed. Duke 3D received an MA for medium-level violence, but it was quickly revealed after release that the game could be modded to remove the lock on the censored content. The OFLC then revoked the classification, which prompted Duke 3D’s Australian publisher Manacomm to write letters to the game’s distributors asking them not to sell any copies until the issue was resolved. The letter, as well as subsequent letters, can be seen here, thanks to the people at Refused Classification, whose comprehensive cataloguing of all films, games, and publications that got an RC has made writing this article infinitely easier for me.

Eventually, the OFLC decided against revoking Duke Nukem 3D’s MA classification, as Manacomm had not been dishonest in presenting the game’s content. This meant that they didn’t have the power to change the classification. It was all a moot point in the end, as a ‘USA Cut’ of Duke 3D was submitted in 1997, and was passed with an MA for high-level violence and sexual references.

A game whose pre-censoring efforts could not prevent an RC was Postal in 1997. The isometric shooter garnered controversy worldwide for its premise – you play as a man who ‘goes postal’ and murders scores of people, including innocent civilians. Even in a toned-down version, it was still deemed to be too much for a country still reeling from a mass murder known as the Port Arthur Massacre, which occurred in 1996. A remake of the game, Postal Redux, was given MA in 2016.

In 1998, Tender Loving Care, an FMV interactive movie inspired by the erotic thrillers that were popular in the '90s, was given an RC. The decision makes sense, it’s a game filled with sex and nudity, and the original interpretation of the rating system is still in place. What’s interesting is that two years later, the game was released as an interactive DVD. Now subject to the film rating arm of the ACB, it received an MA.

Australia ratings become (somewhat) more permissive

In 2003, the Australian games rating system became more in line with film classification. Not completely – still no R 18+ rating in sight – but still far more lenient than it was previously. The general rule was that strong violence and themes (including implied sexual violence), sex, nudity, and drug use were permissible if ‘justified by context.’ This is a nebulous term, and very much open to interpretation by the assessors, but it seems that some major sticking points, such as sex being linked to a reward or illicit drugs having positive impacts on the player, remain past what is allowable according to the ACB.

Rockstar repeatedly receives RCs

The saga of Rockstar’s classification issues in Australia started with an act of hubris that turned out to be very costly. After the first two games in the series received MA ratings, Grand Theft Auto III publisher Take-Two Interactive assumed the third entry would be the same and proceeded to release the game in Australia in 2001 with an MA sticker before a rating was finalised (this was before the change in rating guidelines). It seems bizarre that that could have happened but somehow it did. GTA III was refused classification, the first game in three years to be judged as such, and all copies of the game had to be recalled. Take-Two tried to appeal the ban to avoid the expensive recall but they weren’t successful. The reason for the ban was sexual violence. In particular, the sequence that was frequently brought up by its detractors: the one in which you hire the services of a prostitute, then kill them and take your money back. A version with the offending sequence removed was submitted and passed with an MA in 2002, but by then GTA III and Rockstar were the biggest things in gaming.

An example of what caused GTA III to receive an RC. Souce: YouTube.

In December 2003, Rockstar released Manhunt – a grimy stealth action game that saw players tasked with killing gang members as part of a snuff film. Its graphic, realistic executions drew the ire of anti-video game violence advocates around the world. A particular kill using a plastic bag to suffocate an enemy was feared to lead to copycat murders by those such as the USA’s infamous anti-games crusader, (now-disbarred) lawyer Jack Thompson. Despite this, the game was originally passed with an MA for medium-level violence.

After articles in the Rupert Mudoch-run Herald Sun criticised the decision to allow Manhunt on shelves and linked the game to a murder in England, members of the Liberal Party (one of two major political parties in Australia) in West Australia called for a ban on Manhunt. At the behest of the WA Liberals, the Australian Attorney-General (a politician that represents the executive branch of government related to the law/legal matters) Phillip Ruddock called for a review of Manhunt’s MA rating. In September 2004, Manhunt’s MA was overturned, and the game was refused classification, causing another of Rockstar’s games to be pulled from store shelves. The game is still effectively banned, as evidenced by a 2011 Steam release of the game quickly being taken down in Australia, with customers receiving refunds. Manhunt’s 2007 sequel was never even submitted to the ACB and as such was never released in Australia.

An example of the violence that lead to Manhunt's RC. Source: YouTube.

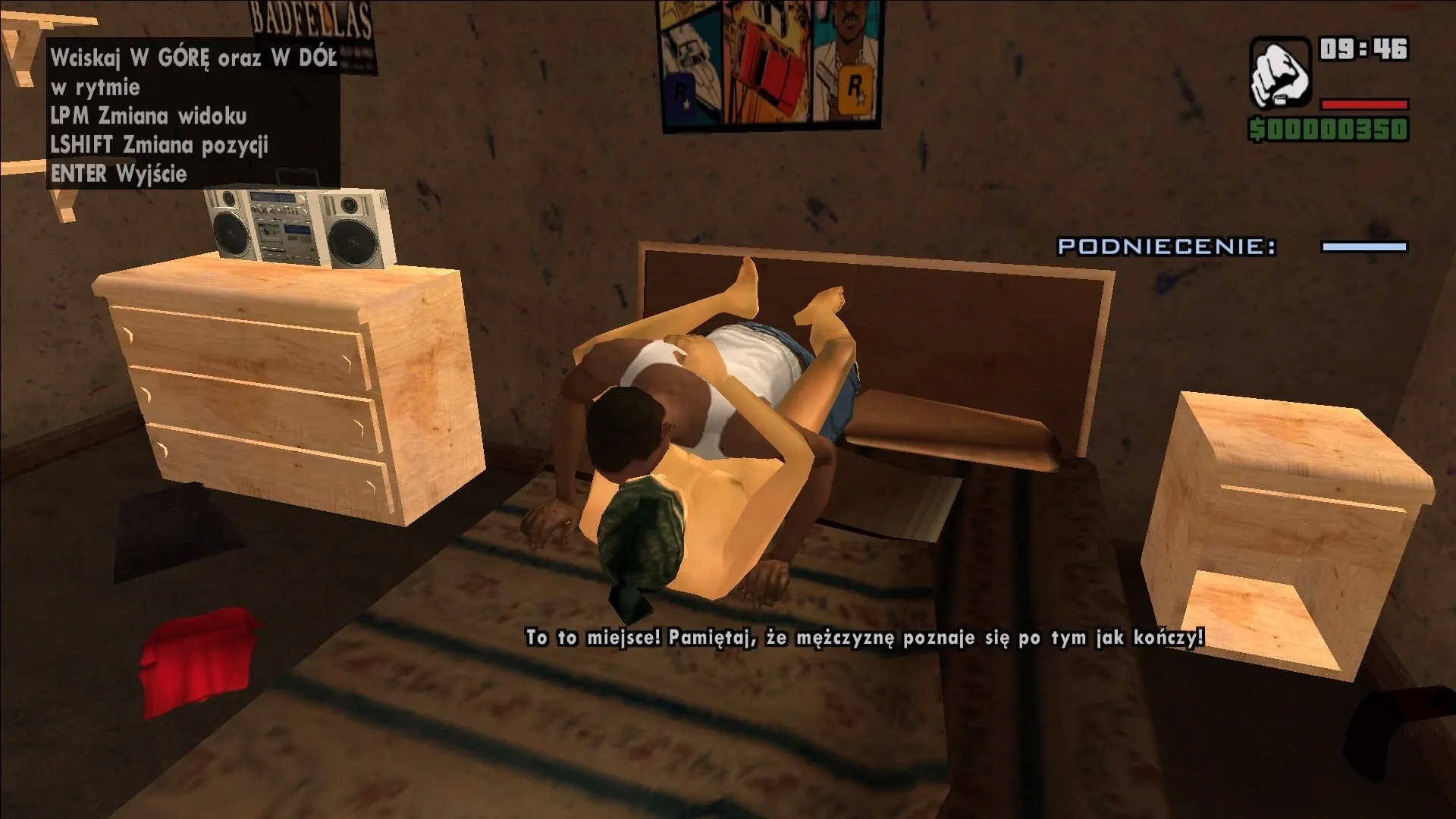

The final game of the ‘Rockstar Games get recalled in Australia trilogy’ is a game that was pulled from sale in the US, too – Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, released on PS2 in October 2004, and on Xbox and PC in June 2005. For those unaware or who perhaps forgot about the infamous ‘Hot Coffee’ controversy, here’s a quick rundown:

- Hidden in the code of GTA: San Andreas was a cut mini-game called Hot Coffee, in which your character, CJ, is invited up to a date’s apartment for ‘hot coffee’ (aka sex). What follows is an interactive mini-game in which you control CJ as he has sex with his date. In the released version of the game, the camera cuts to an outside shot with sound effects implying sex.

- Modders found this mini-game in the code of the PS2 version. When the PC version was released, a mod unlocking the mini-game was created. When news of the mod got out, it became an international incident.

- In the US, San Andreas’s M for Mature rating was replaced with the AO (Adults Only) rating, which meant that major retailers pulled the game from shelves.

- Like Manhunt, San Andreas had its MA rating revoked, and the game was pulled from shelves.

- By September, copies of San Andreas with the mini-game completely removed from the game were released and original ratings were restored.

Banned for graffiti?

GTA III and Rockstar’s impact on the gaming world was immediate. Competitors began to pump out games that tried to match GTA III’s open-world gameplay, gritty settings, and more mature themes. Or failing that, matching them with salacious content (looking at you, BMX XXX). The GTA-like open-world game The Getaway, a gory shooter based on The Punisher, and 50 Cent: Bulletproof were censored after receiving an RC. Other similar games, such as an adaptation of Reservoir Dogs, Postal 2, and the drug-filled Narc also received RCs and didn’t see release in Australia. You can see, even if you don’t agree, why these games were given RCs. However, one game from this mid-2000s batch of RC games stands out for not including extreme violence, drug use or sex – Marc Ecko’s Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure.

Getting Up is a stealth action game that doubles as a homage to street art culture, with spraying graffiti art making up a large part of the gameplay. In 2005, the game’s pending release was protested by police and politicians in Queensland, including state premier Peter Beattie, who claimed the game glorified graffiti and other illegal activity. Despite this, Getting Up originally received an MA in 2005 for strong violence and strong themes.

After this decision, the Queensland government continued to protest the game, with the WA government joining in. Phillip Ruddock once again intervened and in 2006 a review overturned Getting Up’s rating and gave it an RC. In a twist and a sign of a changing media landscape, a website called quicky.com.au began to sell Getting Up as a digital download in 2007. With the site’s server based in the US, the ACMA (Australian Communications and Media Authority) was unable to enforce the ban on the game unless there was a ‘sufficiently serious’ reason to bring in law enforcement, such as child pornography. Quicky no longer exists but Getting Up is now available on Steam, published by Devolver Digital, whose run-ins with the ACB will be discussed shortly.

Morphine or Med-X: The Fallout 3 saga

In 2008, Bethesda was preparing to release the long-awaited third entry in the post-apocalyptic RPG series Fallout, when they came across an unexpected issue. Fallout 3 was given an RC in Australia due to content that was judged to promote or encourage illicit drug use. The issue was that the player was able to use drugs to gain positive effects. In Fallout 3, there are various ‘chems’ that give you a temporary buff, most are fictional drugs but one of them was morphine, which you could inject and as a result get temporarily increased damage resistance. Despite the fact there was the drawback of a 10% chance of causing addiction, which caused negative stat changes, Fallout 3 was still judged to be promoting drug use. This made headlines on gaming sites worldwide for two reasons. Firstly, because one of the biggest releases of the year was banned in Australia. Even more, the version censored for Australia, which renamed morphine to Med-X and removed the injecting animation, was the one released worldwide.

With the ACB’s approach to classification once again in the spotlight, the calls for the addition of an R 18+ rating grew louder. However, the campaign for the R rating hit a roadblock in the form of South Australian Attorney-General Michael Atkinson. The Labor politician was unequivocal in his want to keep the rating limit at MA. His reasoning was that it would “greatly increase the risk of children and vulnerable adults being exposed to damaging images and messages.” Why did Atkinson’s position matter? Well, for a law amending the rating system to pass, all state and territory Attorney-Generals had to vote unanimously in favour. Atkinson’s public statements on the matter meant that he was a target for much criticism from Australian gamers and games journalists alike, as well as being a target for Yahtzee Croshaw, whose Zero Punctuation series was at the height of its popularity when the Brit was based in Australia.

The long (but not too gory) fight for an R rating

Developers of games with high levels of violence and mature subject matter continued to face a South Australian politician-shaped hurdle when it came to releasing games in Australia. AAA shooters including F.E.A.R 2, Alien Vs Predator, Left 4 Dead 2, and House of the Dead: Overkill were all given RCs and had to censor their releases or appeal to the ACB to get an MA. Meanwhile, the gory FPS reboot of Syndicate was never released in Australia after receiving an RC and the new Mortal Kombat was given an RC, had an appeal denied, then had the PS Vita version banned as well. As the chorus calling for an R rating grew louder and more public, Michael Atkinson remained firm in his opposition. However, in 2010 Atkinson decided to step away from his duties as Attorney-General in a move toward retirement. With the sole hurdle removed, Australia was finally on its way to an R rating for games.

In December 2010, it seemed that it was a matter of when, not if, an R rating would be introduced, as Australian Attorney-General Brendan O’Connor released the results of a phone survey that showed 80% of the 2,226 surveyed in favour of introducing an R rating for games. In July 2011, the state and territory Attorney-Generals agreed on the introduction of the R 18+ rating. The NSW Attorney-General abstained from the vote but it had no effect on the outcome.

Australia finally gains an R 18+ rating for video games

Things can often take a long time to come to fruition in government, especially during an especially tumultuous period for Australian politics (from June 2010 to the end of 2013, Australia’s Prime Minister changed four times). It wasn’t until January 2013 that the R 18+ rating was finally introduced for games with an amendment to the National Classification Code. With this, the guidelines for what would be refused classification changed. There were now three broad reasons for a game to be refused classification:

- Games that depict, express, or otherwise deal with matters of sex, drug misuse or addiction, crime, cruelty, violence, or revolting or abhorrent phenomena in such a way that they offend against the standards of morality, decency, and propriety generally accepted by reasonable adults to the extent that they should not be classified.

- Games that describe or depict in a way that is likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult, a person who is, or appears to be, a child under 18 (whether the person is engaged in sexual activity or not).

- Promote, incite or instruct in matters of crime or violence

If this seems a bit vague, what is more illuminating is the section that details what is and isn’t allowed as part of an R 18+ rating. It's worth noting the clear distinctions between film and game classification.

The first game to receive the shiny new R 18+ rating was Ninja Gaiden 3: Razor’s Edge. Another entry in the gory action series, Ninja Gaiden Sigma 2 Plus for the PS Vita, was also amongst the first R-rated games, alongside Mortal Kombat: Komplete Edition, which finally was able to reach Australian shores. Once the R rating was in place, twelve games that were previously rated MA were reviewed to see if they required the new higher rating. The dozen included The Walking Dead, Company of Heroes 2, Gears of War Judgement, and Deadly Premonition, which had a delayed Australian release due to concerns over getting an RC. None of the games had their ratings changed.

And this is where the history of contentious decisions by the ACB ends.

At least, until June.

Amphetamines, anal probes, and crying koalas: the RCs keep coming

It took less than seven months for the first RC of the R 18+ era, and it was a big release. The irreverent open-world action game Saints Row IV was refused classification on two grounds, both of which show that despite the new rating, little has changed in the thinking of the ACB. The first reason was the inclusion of a weapon called The Rectifier, which was a part of the pre-order DLC. The phallic ‘anal probe’ weapon was used by jamming it up someone’s rear, which set off a missile that sent them flying and then exploding. The second was a mission in which players took ‘alien narcotics’ that gave them extra superpowers (you already have superpowers and are the president of the USA, to get an idea of the game’s tone). The former was considered sexual violence, and the later was drug use related to incentives or rewards. The weapon was considered okay on appeal, but the mission had to be cut and the Australian version of Saints Row IV got an MA.

The Rectifier in action. Source: YouTube.

Later that month, zombie survival game State of Decay also received an RC for drug use related to incentives or rewards. Similar to Fallout 3 in 2008, in State of Decay players can take various real-world drugs – including methadone, morphine, amphetamines, and stimulants – to regain health or boost stamina levels. And like Fallout, a workaround was needed. So, for Australian audiences, these drugs became vitamins, and State of Decay passed with an R rating.

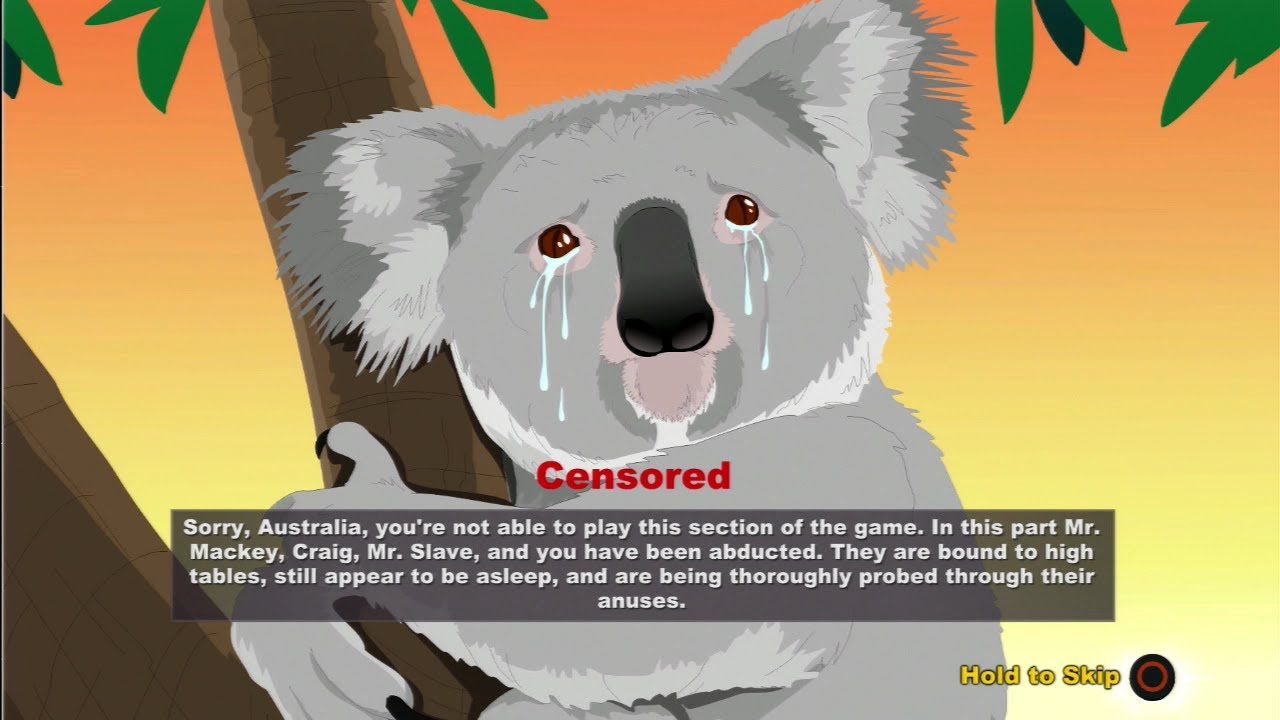

Another AAA 2013 release that required censorship was South Park: The Stick of Truth. This case is notable not just because it involves South Park, a franchise that has pushed against the boundaries of classification (and good taste) but because it took four separate submissions before finally passing with an R rating. Under the title Codename, an uncut version of The Stick of Truth was submitted. There were two sequences that caused the RC. The first, once again, involved anal probes, as various characters fight off aliens who are being probed with dildo-like devices. The ACB declared this to be sexual violence involving children. Another problematic scene involves Randy Marsh, dressed as a woman, receiving an ‘abortion,’ which is controlled by the player. After a failed second attempt, a PC version, also under Codename, was passed with an R.

Now satisfied, a fourth multi-platform submission under the game’s real title was passed. The offending scenes were replaced with an image of a crying koala, accompanied by a description of the censored scene that clearly mocked the forced changes. Similar screens were in the European version of The Stick of Truth, where the game faced the same classification hurdles.

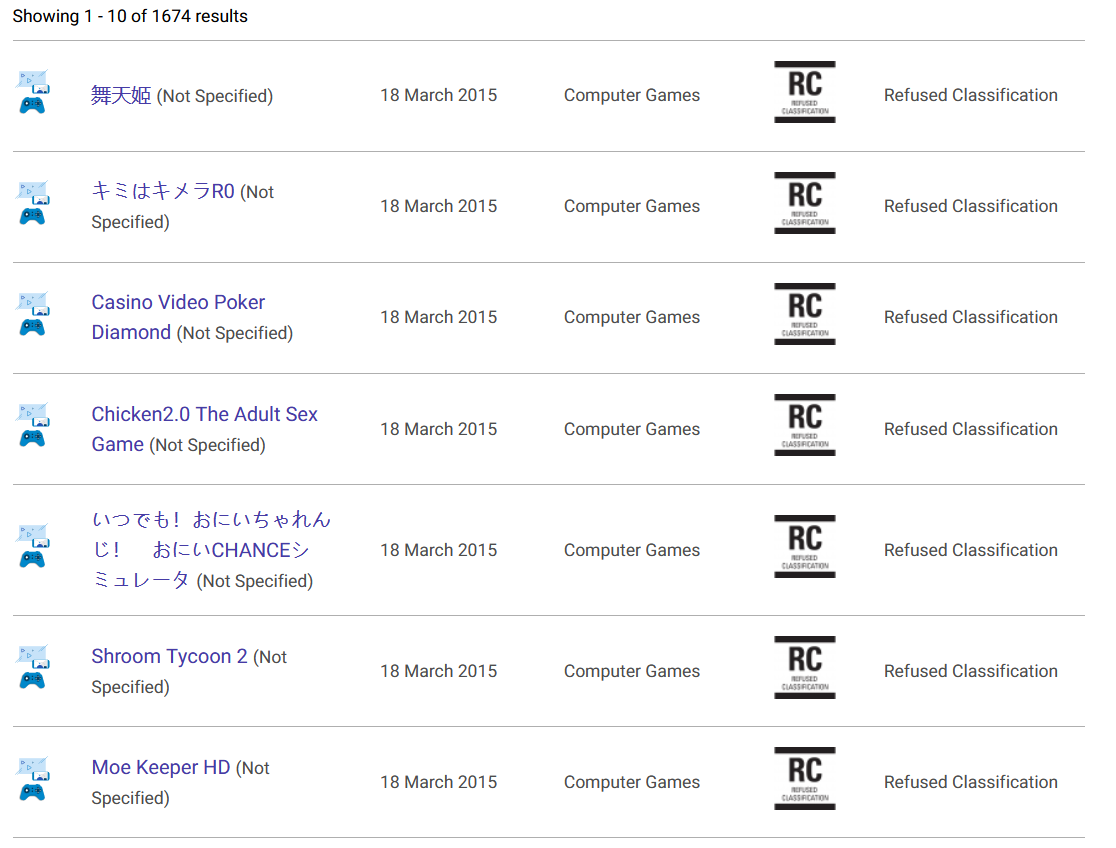

The ACB joins the IARC and the number of games rated...OMG

With digital distribution not only becoming the norm in gaming but opening up the industry to anyone with the means and drive to create and sell a game, there had to be a change in the way games were classified. Enter the IARC (International Age Rating Coalition), which was formed in 2013. As per their website, the IARC “simplifies the process by which developers obtain age ratings from different regions around the world by reducing it to a single set of questions about their products' content and interactive elements.” It is essentially an automated version of game classification that has been embraced by many regions – including the US, Europe, and Australia (which joined in 2015). It has also been accepted by most major digital storefronts, such as all console stores, Google Play, and the Oculus Store (no Steam, though).

While physical releases still need to submit to the ACB, all digital releases on the participating storefronts have to pass through the IARC. All of them. This means that every slapped-together Android phone game has to be classified. There have been over 2,400,000 games submitted in Australia via the IARC since March 2015. That’s a lot of games. To go with this, over 1,600 games have been given an RC. There is a logic to all these bans, especially if you can see the hard-line stance towards interactive drug use, sex, and sexual violence that has persisted even after the introduction of the R rating. For example, if someone submits a game for the Google Play Store, and it’s a basic 2D platformer called Super Weed Bros and instead of a mushroom, you power up with a blunt, that’s getting an RC. Likewise if you submit a cheap strip poker game, or a dodgy slot machine game. However, there was some incongruity between the IARC and the ACB.

The indie game explosion faces the ACB

The IARC has been a successful endeavour worldwide, with game classification becoming more accessible and easier for developers, particularly indie teams. However, the automated IARC and the people at the ACB don’t always see eye to eye, despite using the same guidelines. Many indie games reached a big enough status where they released physical versions, which then had to be rated by the ACB. Some indies pushed boundaries with their content and as such had issues with the ACB. Others felt the force and confusion that comes with a surprise RC.

Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number, is a sequel to the ultra-violent top-down shooter that was a breakout hit for developer Dennaton Games and publisher Devolver Digital. The game received an RC in 2015 due to a scene containing the player character engaging in sexual violence. The scene in question – which is part of the tutorial level that is revealed to be a film shoot – is flagged at the beginning of the game, with an option to skip the scene appearing beforehand.

Devolver Digital released a statement that supported Dennaton’s vision, criticised the ACB, and stated that a censored version would not be submitted. When pressed on the matter, Dennaton’s Jonatan Söderström told Australians to ‘just pirate it after release.’ One of Devolver’s 2016 releases, a multiplayer party game starring penis-shaped characters called Genital Jousting, was not even submitted to the ACB or IARC. In 2019, a collection of both Hotline Miami games for the Nintendo Switch was rated MA by the IARC. Within 24 hours of its release, it was pulled and the MA rating was withdrawn by the ACB.

Source: YouTube.

In May 2018, the much-hyped indie game We Happy Few was given an RC by the ACB. The game features a dystopian version of London, where citizens are required to take an addictive drug called Joy that distorts their surroundings, making the dilapidated, war-torn city look colourful and psychedelic. If you didn’t take Joy, you were hunted by the police. Drug use in the game was originally judged not to be justified by context. Developer Compulsion Games and publisher Gearbox Software appealed the decision and subsequently had the RC overturned and changed to an R. However, this was not the end of the rating troubles for the game. In August, We Happy Few was submitted to the IARC and received an RC. The ACB then changed that decision to an R, in line with the reviewed decision.

Another source of rating confusion came from the surprise RC for DayZ in 2019. The hit zombie survival game, which had been in early access on Steam since 2013, had been rated MA on four separate occasions through the IARC, but was refused classification when it went through the ACB for the multi-platform full release. What was the reason for this? That phrase again: drug use related to incentives and rewards. Specifically, the fact you can restore health by smoking marijuana, which mirrors the Fallout 3 situation (and the made-up joke example I used earlier). Like with Fallout 3, developer Bohemia Interactive decided it was easier to change the game for everyone and removed joints from the upcoming version of the game.

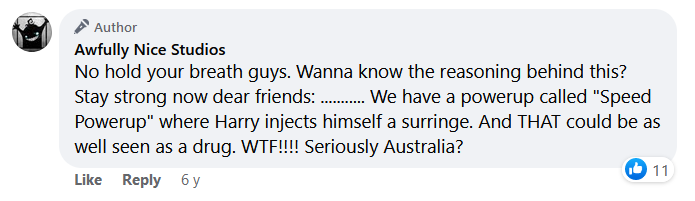

DayZ was far from the only game to run into the ACB’s strict definition of drug use as an incentive. The most egregious example came from cartoony side-scrolling The Bug Butcher, which received an RC for, well, let’s hear it straight from the developer, Awfully Nice Studios.

The speed injection was replaced with ‘boot juice’ and they received an M for their game.

Cultural differences

Every country has its own differing standards when it comes to ratings, which can often be attributed to cultural values, or at least the cultural values of the country’s politicians (as seems to be the case in Australia). For example, the USA is very lenient on violence, but strict on sex and nudity. Germany is strict on violence and until 2018 did not allow any Nazi or white supremacist imagery. Japan, too, is strict on violence, and also on sex. However, they do allow a high degree of what is generally referred to as fan service: giving the (horny, straight male) fans what they want. This is to say, in many Japanese games, as well as anime and manga, there is a degree of extraneous sexual content – whether it be innuendo, revealing outfits, nudity, or implied sexual acts.

Where does the ACB come into this? Well, one of their several bugbears, along with sex and drug use as incentives and depictions of sexual violence, is the second item on the list of reasons for an RC: an offensive depiction of a person who is, or appears to be, a child under 18 (whether the person is engaged in sexual activity or not). Sometimes, in Japanese media with fan service, the female characters involved, to use the ACB’s specific language, appear to be or are under 18 years old. As previously niche JRPGs, dungeon crawlers, and visual novels became more popular, and thus warranted an Australian release, several games ran into a rating hurdle that they didn’t have in their native country or any other for that matter.

Introduction to the characters of MeiQ: Labyrinth of Death.

The first notable instance of this was in 2016, when dungeon crawler MeiQ: Labyrinth of Death for the PS Vita, which was given a Teen rating in the US and 12+ in Japan, was given an RC. The reason given was that in the character menu, you are able to run your finger over the touchscreen to make the breasts of the female characters move. Most of the characters have large breasts and skimpy outfits, but one character is flat-chested, smaller, and childlike in dress and demeanour. This was declared to be ‘simulation of sexual stimulation of a child.’

The ACB’s hard-line stance on games with fan service featuring characters that appear to be minors has continued to this day. Valkyrie Drive Bhikkhuni, Song of Memories, and Omega Labyrinth Z are all among similar games receiving an RC (the latter's entire western release was cancelled due to rating issues).

The ACB today and into the future

In the last two years, there have been two cases of high-profile games that had already been released in other forms – Disco Elysium: The Final Cut and Rimworld - being given an RC for drug use as an incentive, only for them to be changed to R on appeal. There have also been two Japanese games, Mary Skelter Finale and Deathsmiles I-II, given RCs for their sexual content, with the latter having previously been rated M through the IARC. This happened with a remake of 1997’s Blade Runner point-and-click adventure game. This is to say that the ACB hasn't changed how they conduct business lately.

There doesn’t seem to be anything indicating a review is incoming or changes are going to be made. There are complaints made every time a major release that is rated elsewhere in the world is given an RC in Australia (for example, there were 199 complaints about the Disco Elysium decision), but they seem to be falling on deaf ears. Game classification in Australia is certainly less of a hassle than it was in the pre-R era, but no amount of bad press seems to phase the ACB.

As to why the ACB has been and continues to be, so strict compared to the rest of the world, I’d like to sum it up with an academic or literary source. But what I have is a very accurate tweet from Tiger Webb, the ACB's language research specialist:

weird how a foundational myth of australia is that we’re a nation of subversive larrikins, when in actuality everyone here is an ultracop

— Tiger Webb (@tfswebb) March 21, 2018

Australia is a nation that is more uptight than it appears. The National Classification Code and the ACB almost infantilise gamers, as they are seemingly unable to rid themselves of the notion that video games are largely the domain of children, even though many of them bear a rating label that indicates that they are for adults only. This seems to be a bipartisan position, so the chance of it becoming an issue in parliament is remote, but you never know, the wrong person may get annoyed at a game’s ban and there could be another chapter to this story.

I’d like to once again give a huge shout-out to Refused-Classification, whose dedication to all things RC and ACB made researching this article much more straightforward than it could have been. And, somewhat begrudgingly, have to acknowledge that ACB's website has been very useful, considering it has every decision listed from Mortal Kombat onwards.