The Hidden Depth of In-Game Texts

What collectible texts and audio logs have to say about their world

Have you ever read a book you looted in Skyrim? It's one of many inessential items you can pick up – in the corner of a guard's barracks, or a cave full of cobwebs. Most players, myself included, wouldn't think twice before selling the books, like throwing junk out of an over-stuffed inventory. Even in games where these collectible texts don't take up any space and can't be discarded, where you acquire them while exploring or after completing side-missions, the most people usually do is skim them. And no wonder: there are so many games coming out every year, and the time you have to play them isn't getting any longer, so wouldn't you rather enjoy playing the game rather than waste time reading the texts inside it?

But spare a moment to wonder, in the universe of each game, that these texts must have a reason for existing. They should have some sort of importance to be chosen as a collectible. In the aforementioned Skyrim for example, every book you can read is set in the same fictional universe, a world where dragons already exist and magic is real. In a world as fantastical as that, is there still room for fictional books–fantasy books–or is everything then true and autobiographical?

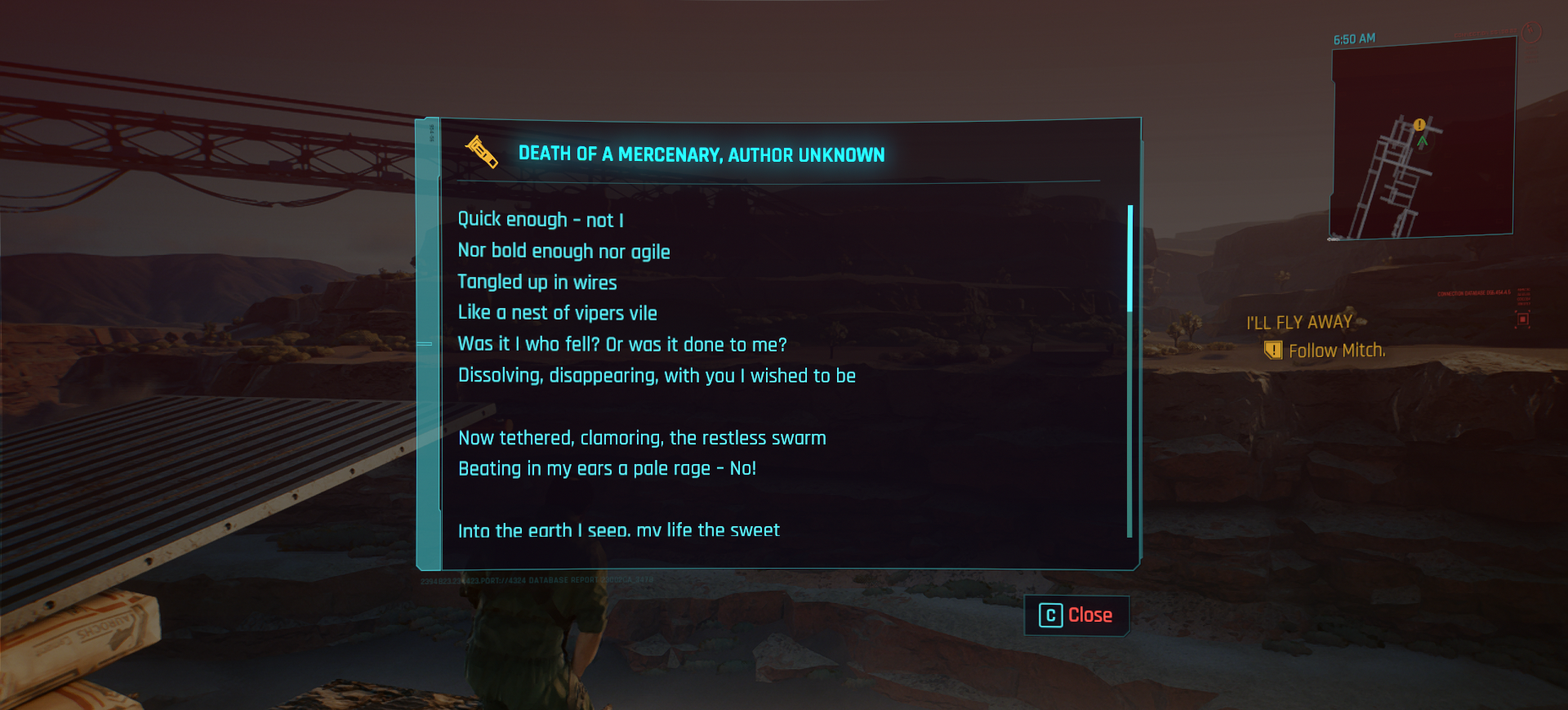

The world of the game affects these pieces of writing as much as these texts paint a more detailed picture of the world they belong to. A poem in dramaspunk 2077 may tell more about the political implications of a world run by corporations, or someone's inner turmoil living in that world, than if that same fact is told explicitly to the audience. It's a subtler way to show how different or similar a video game world is from the player's own.

Tools for immersion

These peripheral additions ultimately serve the purpose of immersing the player more deeply into a simulated world. In-game texts give the visual environments more credence. Graphical fidelity does the job of creating the appearance of a world and the atmosphere, but these texts fill it in with history. You find a dead body impaled with a pen in Fallout. Then you find a computer terminal with a log that tells you who they were before you found them and what happened. You get to read about a now-irradiated skeleton's final moments.

It's like seeing a painting in a museum. The work hits you with an abstract feeling and then reading the description and getting the specific story further defines the image. The level design, models, and textures set the stage, while these optional reading materials write the drama. Together they create the mood and tone for the microcosm of their respective game worlds. With modern games so expansive and lasting for dozens of hours, texts make repurposed assets scattered around the world feel special and particular, distinguishing them from one another. A regular knight's helmet or garden-variety sword in Elden Ring may be infused with tragic poetry after the player reads a single line of its lore.

In Remedy Entertainment's Quantum Break, there is a hidden side story where one of the enemy's staff writes fan fiction about his life, in hopes of winning the heart of one of the game's other antagonists by making a movie out of his script. This story is only available through finding emails with the attached script in some of the levels. It parodies the game's story, using ideas and characters in a comedic way that involves time travel, which makes sense considering the organization the writer works in deals with time travel.

This easily missed moment makes the enemies you fight and kill feel somewhat like real people, reminding you that the stereotypical evil organization is not just comprised of faceless uniformed goons, but also lovesick nerds. This grounds us in the story, complicating the background characters by adding personality to the world. These texts could also play with genre, allowing developers to slip a light-hearted reprieve into an otherwise serious game.

Tools for insight

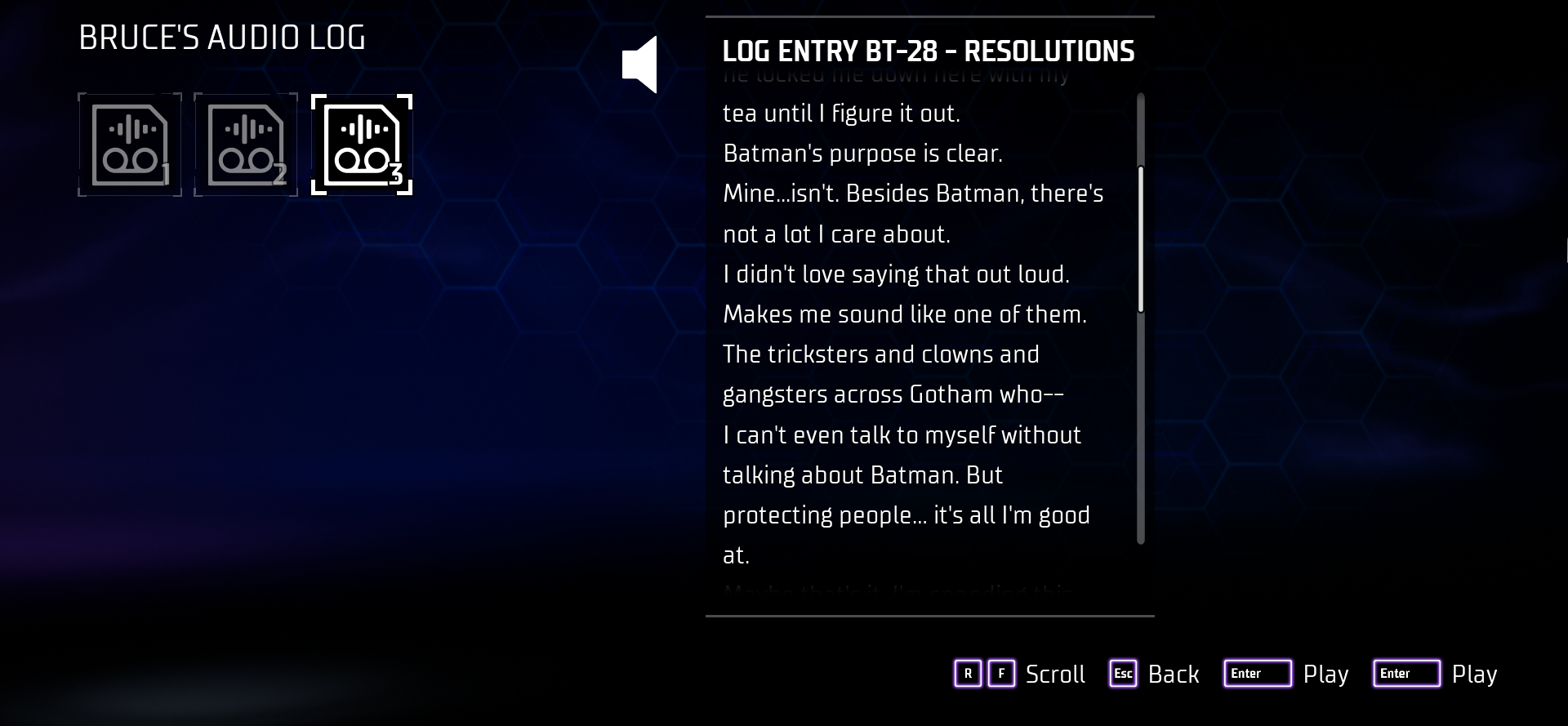

Another version of these collectibles are audio logs, voice recordings you find in the world, an identical form of information dispersal that is basically just a voice-acted version of the regular texts. But because it's voice-acted, sometimes these are more essential and richly written than the former. In Gotham Knights, there is an optional time trial challenge where, when finished, the player is rewarded with Batman's voice recordings, from his first year to his last. Putting aside the game's main plot, these dozen or so audio logs tell a supplementary story inside the world, one that only makes sense in the context of the game. Through these, the player hears Batman's struggles and his evolution from a younger man doubting his future to a determined hero with a family.

Here, the player gets a chance to discover a story without having to play as that character, by discovering and putting pieces of their life together. Something as simple as these logs differentiate this Batman from other versions, showing a more vulnerable side that he never shows to the world.

Listening to these audio logs is as intimate as discovering someone's journal or love letter, especially because you're not the intended recipient. In video games, the world is often designed around the player, a sandbox where you–the protagonist–are intended to experience all the bombastic action and boss battles. But these texts scattered around the map are not intended for you, they are intended for the world, thus making it all the more special when you read them. It's like perusing someone else's school yearbooks or looking through someone's weathered diary. These collectible texts are clues that make the player a detective, uncovering the mystery of each game world and the richly written characters who live in them.

Metal Gear Solid V takes this narrative delivery device a step further. There, the context of the story can only be comprehensible if listened to through cassette tapes. Some of these are so detailed they're like audio dramas playing out, complete with twists and reveals. Most of the plot information and background details happen in these tapes, and they fill in the blanks the cutscenes left behind. Creator Hideo Kojima experiments with cutscenes being cinematic playgrounds where the action happens. They're used for completely visual storytelling, with most of the exposition happening in the recordings. These discoveries are essential if players want to know what happens, but complementary if players just want exciting gameplay and enticing visuals.

What's interesting is the non-linearity of these texts. In both Gotham Knights and Metal Gear Solid V, two wildly different games, the player doesn't acquire these voice recordings in chronological order. Some parts about something that happened earlier in the story are only revealed and acquired by the end. Unlike regular gameplay and cutscenes, they can be experienced in any order. The first piece any player reads or listens to may be different for everyone. They are jigsaws that can be put together from any side or angle but always end at the same place.

If playing video games is vacationing abroad, seeing the sites and set pieces, then reading in-game texts is going to the local library and catching up on its history and the important people in it. Each one is unique and a piece of the larger puzzle of the place, no matter how seemingly small and minute. Like rummaging through an antique store, everything tells a story. Providing these stories within stories is something special that video games as a medium can do. Akin to annotations in a novel or comic book, these optional footnotes give depth to a manmade world, as if it existed before the player set foot in it, and will exist long after the player leaves.

More than excess data that fills the memory of the game, these texts make the world feel lived-in. Though there may be exceptions–collectibles that are filler, empty exposition, and video game jargon, assets that would likely be used just to fill a tavern shelf–you may also come across truly well-written things. You may find logs that leave you listening in on other characters' most private moments. You may read someone's last words to their loved ones, or a hopeful message ignorant of an upcoming catastrophe. In-game texts provide an opportunity for players to window shop on side characters' tragedy or comedy.

The next time you discover a pixelated piece of paper or a notification pops up in your HUD about a new audio log, maybe you should check them out. Experience for yourself the lengths that some of these writers go to putting tear-jerking short stories into something that most people may not even read. Try not to write them off; use these collectibles to take a breather after an intense action scene or challenging section, and just read or listen to these as your character would in the context of the game. You may just chuckle, or you might shed a tear, or maybe even find the thing that makes you fall more in love with the world.