The Evertale Controversy

Can lore exist independent of a game as part of false advertising?

What is game lore without the game matching the advertised jumpscares and horror?

It feels weird having a fascination with fiction that scares you. I don't mean if you enjoy reading Stephen King and pondering about the power of writing; it's how the YouTube algorithm works. You may have just idly googled a game after seeing a random reaction video that shows a jumpscare or moment of terror. An interest in Omori can prove profitable. In theory.

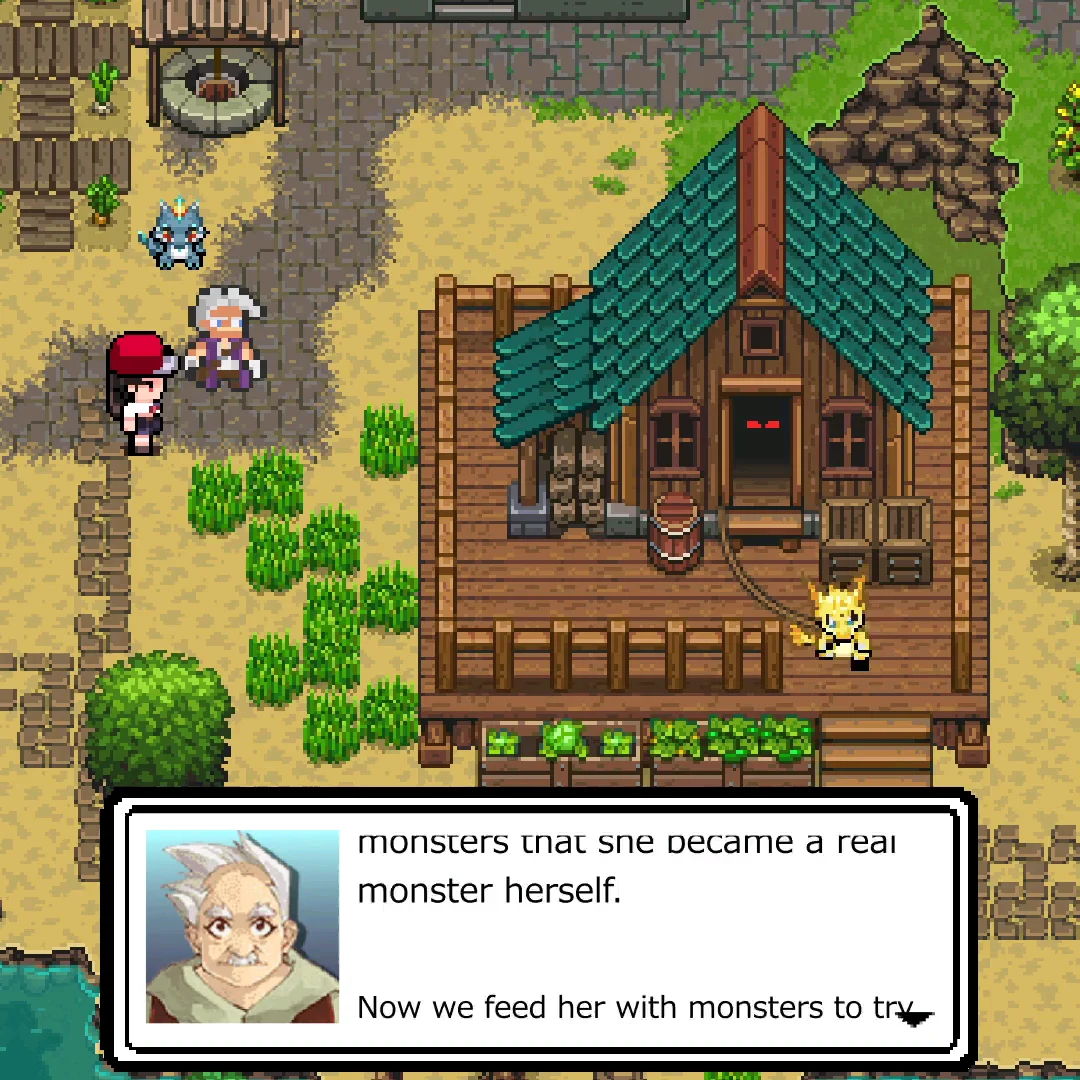

Game Theory came out with a video about Evertale, a 2019 mobile game. They advised viewers not to download it because the game is a pretty basic monster-catching title you can play on your smartphone, but the advertising tells a different story. Literally!

In the Evertale ads (and there are three hours' worth of them), the player character has done something terrible and the gameplay goes wrong. White text talks about "consequences" and a need to "move on", which definitely sounds like Omori. Jumpscares and art shifts ensue, depicting glitches and some rather unsettling corpse sprites.

Does any of this actually show up in Evertale? Apparently not! And that is disappointing.

The story seems to be that in this world, the "breeders" (aka the humans) go out and catch monsters, either making them fight to the death or cooking them for meals. Some monsters have caught on, realized they can capture humans, and return the favor. That by itself would be an interesting premise for an actual horror game. You can deconstruct the concept of games like Pokemon in this way.

MatPat believes that the six humans we see are actual characters that are trapped in a glitching simulation, designed to torture them. That is why they seem to recover from death relatively quickly, ending up in various planes after losing monster battles. Their memories have been wiped, and the only way to escape is if they can regain their memories and accept the consequences of their actions.

Do I believe this necessarily? I admit I'm skeptical. After all, we only have the ads that tell this story. Evertale is useless at confirming if these are true.

Can Game Lore Exist Without a Game?

Emotionally, I don't think so. If you are creating lore to stand on its own, like the Slenderman mythos, then you can do what you like.

If you are connecting lore to actual dev work, however? Then you need a connection. If you are changing the art from three-dimensional graphics with anime girls to RPGmaker sprites, there has to be a reason. Omori's many art shifts came from the fact that Sunny, the player character, has trauma coloring his perspective.

The Evertale lore in the ads would not be an issue if it existed separate of the 2019 mobile game, explained as a campaign to get into the Halloween spirit early. You could have a disclaimer that none of these stories is canon, this is just a bit of fun. That the lore doesn't explain this is misleading.

Why Do We Crave Surprise Horror in Cutesy Games?

A good question. Some horror games are upfront that they have things that go bump in the night. They tell you that the monsters are there waiting in the shadows, or that you have to navigate past some terrifying visuals.

There have been a few games, however, that aim for a bait and switch. Omori isn't the only one; Doki Doki Literature Club, Undertale, and Deltarune do the same thing. They may look cute on the outside or sweet, but there is a dark undertone. You want to look away, but now you are drawn into this jump in the narrative.

Wait a minute, I've heard of this before: this is Lost Episode or Corrupted Videogame creepypasta lore! If you were on the Internet in the 2010s, you may have caught mentions of a story like "Candle Cove" that had fictional users talk about a show they forgot.

If you were reading creepypasta on Tumblr or seeing it passed around, there was this desire to scratch the surface of something deemed safe for kids. Lost episodes or corrupted video game tales that said certain cartridges and VHS recordings of old television shows were haunted. You got reminders of how strange PBS television could be or the shows that your parents recorded.

The big problem with creepypasta, of course, was no quality control because people who share their stories online rely on a moderated Wiki to share their tales in one central location. Lost episodes were trying to rewrite canon, and ended up missing the mark. If you know how long it takes to make one animated short and had memories of Disney's early Nightmare Fuel within "Pluto's Judgment Day," you can't take the Suicide Mouse story seriously. The same goes for claiming that a Magic Schoolbus lost episode featured the Soviet Union. If you watched the Magic Schoolbus, the nightmare fuel in the space episodes was fairly consistent.

With video games, the amount of moving pieces required to create a decent whole makes the quality control better by default. Players will ignore the games that fail to make their jumpscares or implications memorable. They will elevate the ones that stay in their nightmares, or daydreaming. Heck, a horror game doesn't even need a jumpscare to stay in the player's mind.

A good videogame can adapt this creepypasta mindset, and allow us to remember what we loved about being a kid. Then it gives the sharp reminder that we have grown up. They have to stick the landing, though, for the answers we seek.

Wanting Answers for Our Disrupted Innocence

We are drawn to the idea that things that seem innocent on the outside are not-so-much on the inside. As for why? It could be a means of coping with the fact that we are not kids anymore. What we thought was safe or reliable gets taken away from us.

In the real world, disruption hurts. We sometimes can't trust that new books or media will save us, or that safe spaces will stay safe. When faith in an established structure breaks, it breaks us as well. The values we were taught fall in the face of hypocrisy and entitlement; trusted authority figures decide that our feelings mean nothing to them. And we have to decide how to rise and live again.

Disrupted innocence in fiction is different. You can use the player character in a game to explore these feelings of hurt, confusion and betrayal. Or you can assess who you really are, and how you ride these waves.

For example, Doki Doki Literature Club is a game all about how we are seeing the world through unreliable lenses. The nameless player character thinks that a childhood friend is roping him into listening to a bunch of her classmates read poetry aloud. He fails to see her depression, or that he is a pawn in a bigger scheme. The visual novel construct falls away as we see it's a story about what you do when you have limited choices in an uncontrollable situation and the price of taking down those barriers. To get a happy ending, the player needs to make a different choice within their control.

Omori has a similar structure. We think we are playing a cute RPG, up until Omori stabs himself with a knife, and we wake up in a house with no electricity. The narration gradually reveals that Sunny is a traumatized body, who has to face his past rather than live in it. Sunny being an unreliable narrator colors the player's experience, which makes the eventual payoff better.

The Evertale Creators Need To Make a New Game

It's quite a feat that Evertale's developers accidentally figured out how to create a better story than their mobile game. I didn't even realize how much effort they had put in until MatPat said that they had three hours' worth. Nevertheless, the problem is that they lied about it. There is no special horror or Halloween event, or that moment of truth.

If they want to gain players' trust back, they need to make a new game. One that shows they know how to tell this story in game form. And that means going back to the creepypasta roots, to determine the story they want to tell. What trauma do they wish to explore, and what is the payoff? Only the creators can tell us. And if they don't? That's on them.