The Diablo We Might Have Had

We almost got a completely different game

Diablo IV has taken the world by storm, and while opinions vary on whether Blizzard's fastest selling game ever is destined for classic status or doomed to become another soulless live-service grind, the one thing that is irrefutable is that the Diablo series has left an indelible mark on gaming history. For me, the peak Diablo experience is Diablo II, though all the entries in the series have at least some redeeming qualities. However, were it not for a handful of fateful design choices back in the mid 1990s, the Diablo we know today could have been a very different beast indeed.

Following a presentation at GDC 2016, David Brevik released a PDF of the original 1994 design pitch for Diablo, by Condor Inc., the developer that would one day come to be known by the name Blizzard North. Condor had been founded in 1993 by David Brevik, Erik Schaefer and Max Schaefer. While some initial work doing console ports (NFL Quarterback Club 95 and 96 for Game Gear and Game Boy and Justice League Task Force for Sega Mega Drive/Genesis) paid the bills, Condor had already started planning for a game that would change the industry forever - Diablo.

It was during the development of Justice League Task Force that Brevik and the Schaefer brothers met their future partners at Silicon & Synapse, the studio who were developing the Super Nintendo version of the very same game. Silicon & Synapse would eventually strike out on their own under the name Blizzard Entertainment, and one of the first relationships they cultivated was with Condor.

A Vastly Different Vision

One of the most interesting passages in Condor's original pitch is in the opening paragraph:

"As games today substitute gameplay with multimedia extravaganzas, and strive toward needless scale and complexity, we seek to reinvigorate the hack and slash, feel good gaming audience."

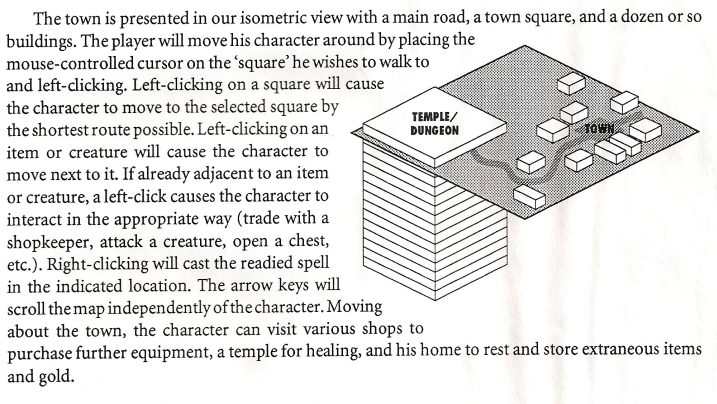

In 1994, the RPG market on PC was indeed dominated by deeply complex RPGs - Might & Magic, Wizardry, Ultima and the seemingly endless cavalcade of RPGs from SSI based on settings of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons table top game. Diablo sought to strip the genre back to its foundations - a sandbox style romp through a deadly dungeon of traps and monsters. The influence of roguelikes is immediately apparent in this ethos (especially with the stated intent of procedurally generated levels), as is the influence of classic table top gaming where players would gather around a table and delve into mysterious dungeons one grid square at a time.

There is a hearty dash of irony in the fact that Diablo was initially a response to the "multimedia extravaganzas" of its day - with grandiose cinematics, celebrity endorsements, seasonal play and a colossal budget, Diablo IV is today the very definition of a multimedia extravaganza.

Today, Diablo is known by the term "action RPG", denoting the frenetic pace of gameplay that overlays the character progression mechanics that often define an RPG. However, the table top gaming influence on Diablo was initially far greater - Diablo started its journey as a turn-based game. David Brevik recalls the excitement of turn-based roguelikes as a major inspiration:

"You're down to one hit point you're frantically searching through your inventory - "Oh my God, do I - do I read this scroll? I don't even have it identified! I don't know what it's gonna do here, but I got like one chance to do something. Should I drink a potion? Do I run away? Do I - oh my God, I'm at a dead end..." Your palms are sweaty, "I've been working on this character for two weeks, oh my God, what am I gonna do..."

By this point in development, Condor had already made a deal with Blizzard Entertainment as publisher for Diablo. As Brevik recalls, Blizzard was impressed by early demos, but had two conditions: it needed to be real time, and it needed to have multiplayer. There was some resistance from Condor, Brevik in particular, but the decision eventually came to a vote, and the team went with real time. The decision proved to be a pivotal one, and Brevik recalls that when the real time gameplay first clicked (no pun intended), it was one of the most memorable experiences of his life.

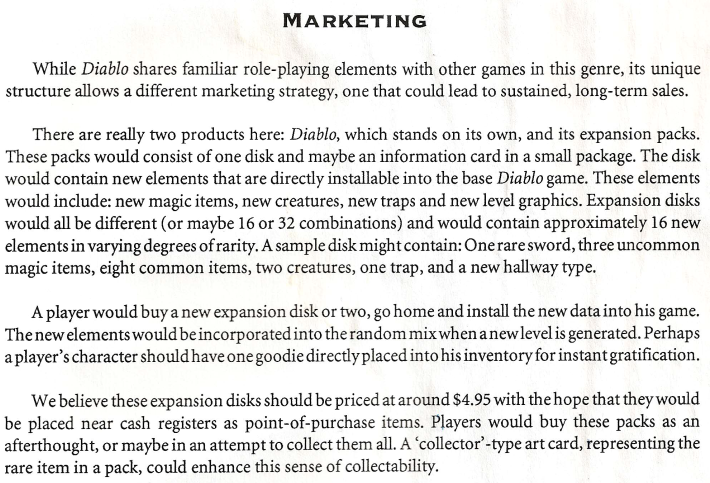

Proto-Microtransactions

When talking about the history of microtransactions in games, many often point to the infamous Horse Armour DLC for Bethesda's The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion. However, the origins of microtransactions stretch back far earlier than that, and one might argue that Condor was one of the earliest modern developers to propose utilising a concept that resembles a modern microtransaction.

The inspiration for this idea was trading card games like Magic: The Gathering. Like a digital booster back, these low-cost discs would sit at the counter of your local games store, a tempting impulse purchase that could add some new content to your game, at a far more enticing price point.

In his speech at GDC 2016, Brevik concedes that the concept simply wasn't realistic - it would have been a phenomenal logistical undertaking for a small, young studio in the days before widespread adoption of the internet. But, as the above passage from Condor's Diablo pitch demonstrates, the strategy underpinning it was incredibly sound, and is widely employed today.

Glimpses of Future Brilliance

Equally fascinating, albeit in a different way, is how resilient Diablo's gameplay loop has proven. Not only has the series left its indelible mark on gaming history, Diablo spawned legions of acolytes and imitators. One of the first "Diablo clones" I played was Westwood Studios' criminally underrated Nox (pick it up from GOG, and get OpenNox while you're at it), which was released in 2000, a few months before Diablo II. Unfortunately, Nox was overshadowed by Blizzard North's sophomore masterpiece. However, it wouldn't be long before more developers would make their attempt at the action RPG crown - Divine Divinity (Larian Studios) and Dungeon Siege (Gas Powered Games) both arrived in 2002, each with their own unique twist on the formula. 2004 saw the arrival of Diablo's most direct competitor with Sacred, the first in a series of three games from German developer Ascaron, and in 2006, Iron Lore's Titan Quest took the action RPG to the Bronze Age. In 2009, Runic Games eschewed the Diablo's grimdark tone with the first game in their light-hearted Torchlight series.

Sixteen years went by since the release of Diablo in 1996, and though many studios made valiant attempts at innovating on the formula, none seemed capable of toppling the series that had its humble beginnings in an eight-page pitch from 1994.

Even Blizzard's own attempt at innovating on the Diablo formula proved contentious. 2012's Diablo III set sales records as expected, but critical reception was marked by sharp divides among the player base. Some players found the artistic direction was a betrayal of Diablo's grimdark origins. Others accused the mechanics of being overly simplistic. The game was embroiled in controversy over launch day issues and a universally criticised real money auction house.

It wouldn't be long before more action RPGs appeared on the scene, each hailed as the "true successor" to Diablo - Path of Exile and Grim Dawn spearheaded this post-Diablo III generation, and many have followed since. And of course, most recently, Blizzard has looked to its competitors for inspiration with Diablo IV, the most recent game in the series resembling a patchwork of everything that came before it.

Almost three decades after the release of Diablo, the fundamental pillars of the genre endure, almost exactly as they were in 1996. Every studio has added their own flavour to the formula, but at the core of the modern action RPG is the same raw and utterly addictive loop that keeps players coming back. It's fun to imagine how different the games industry could have been, were it not for a few fateful tweaks to Condor's original pitch.