The Day My Father Understood Games

Finding common ground with the non-gamers in our lives

Games have, for many years now, been an accepted and well-understood pastime. eSports is a multi-million dollar industry, many households have two or more devices that are used for gaming, and the success of TV series like The Last of Us have demonstrated that games are gaining broad acceptance as an art form that has influenced other forms of media.

This isn't the games industry I've always known and loved, however. I am a child of the 1980s, and while I couldn't claim to be a first-generation gamer, I would argue that I am probably the last generation to live in a world that saw gamers as a subculture of outcasts and social pariahs. During my time at high school, gaming was gaining increased social acceptance. Console gaming had spearheaded that, but PC gamers like myself continued to be perceived as "nerds" who were often on the receiving end of a little teasing. It rarely escalated to bullying, as even the "cool, sporty kids" were enjoying some GoldenEye 64 or Resident Evil from time to time. But gaming, and PC gaming in particular, was still regarded as a bit of an anti-social niche hobby.

For me, this broader lack of acceptance of gaming was compounded by the fact that my parents were extremely lacking in technological literacy. My mother had come from a former Soviet bloc country where exposure to western technology was mostly unheard of. Both work and play were synonymous with sweat and grime. My father was born in 1943, and had grown up in post-war Scotland. He and his three brothers, mother and father had all shared a two-room flat in a poor part of Aberdeen. His father had died in 1953, leaving my dad's mother to struggle with four boys and little money. A rugby scholarship and the personal connections of my apparently very charismatic grandfather had helped my father find a way out of his impoverished upbringing, eventually leading to his graduation from Strathclyde University in Glasgow. My father was well-read and, in the Scottish tradition, very progressively minded. However, he still held on to that veneration of the "elbow grease" approach to life, a perspective that has very little room for the sedentary, cerebral hobby of being a gamer.

Neither of my parents was particularly enamoured of my passion for gaming. From their perspective, they saw games as a simple button-mashing affair where the goal was to achieve a high score, and they had little interest in validating their perceptions of it. They were rarely hostile to the hobby, and I certainly enjoyed one of the benefits of having an Eastern European mother who indulged her little boy's passions with a PC game for a birthday or Christmas. This was of course balanced by the other side of the coin - an Eastern European mother's fury when you played too many games. But, for the most part, my parents were accepting, though not totally understanding, of my passion for games.

I am thankful to say that my relationship with my father was always very strong - he was, unlike many of his generation, deeply affectionate and warm. As a child, he took me out every weekend to museums, bush walks and all manner of local events. The teenage years were sometimes a challenge (as expected), but as I emerged into young adulthood, our relationship flourished, and I spent many hours in deep conversation with him as we shared our passion for story-telling, jokes, philosophy and nostalgic anecdotes. We frequently engaged in lengthy debates; long past the point where others would walk away in exasperation, my father and I would continue as though we were Ancient Greek philosophers, verbally sparring in the marble forums.

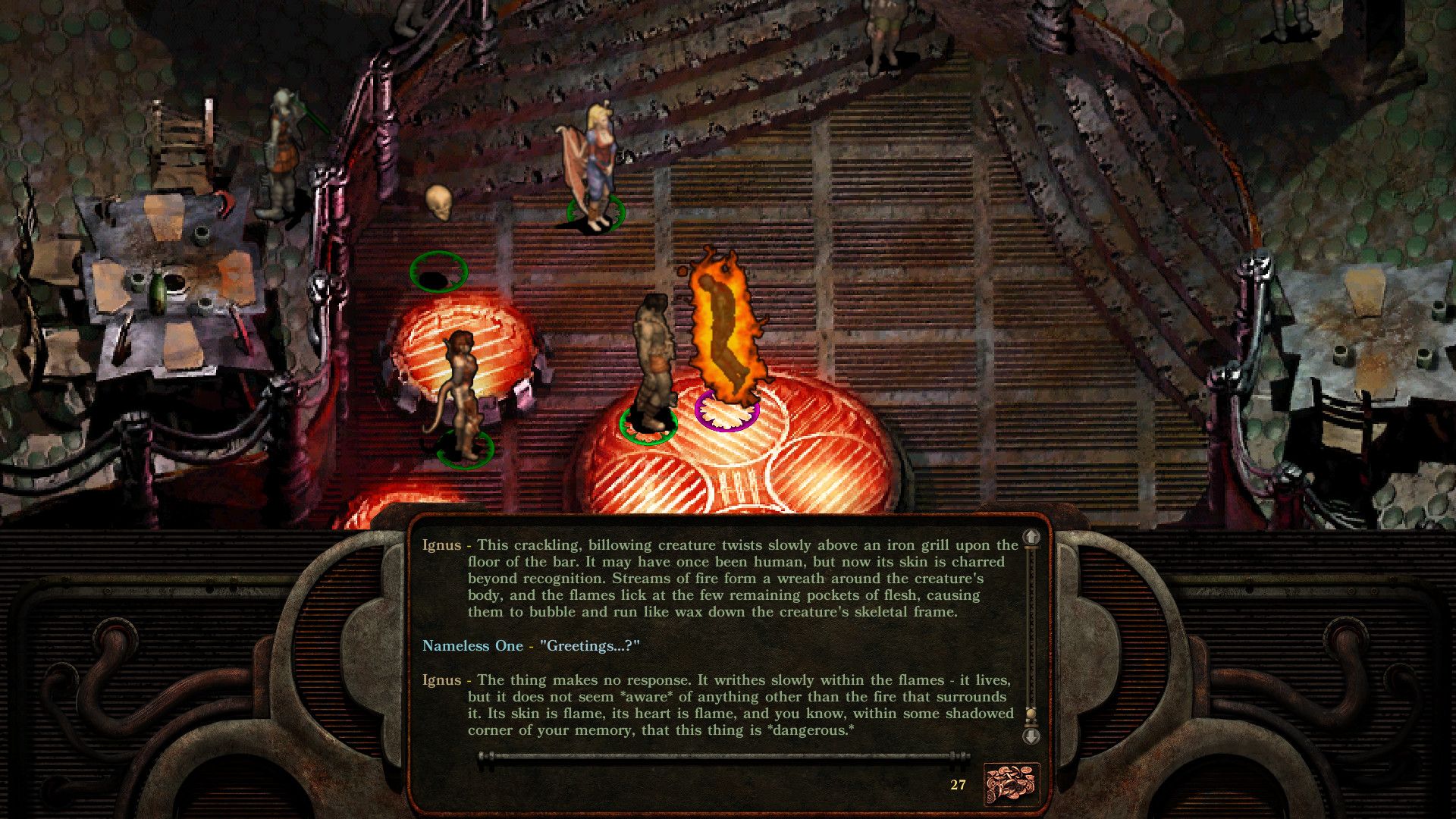

A favourite time of year for these chats was Christmas. Once lunch was done and the two of us had consumed plenty of beer, wine and/or whisky, we would launch into a discourse that would undoubtedly set my mother's eyes rolling. A frequent line of conversation would begin with my dad sharing his critical analysis of a certain classic movie or novel. I would sometimes segway into a discussion of a game I had played, sharing with him the witty dialogue of a LucasArts adventure like Sam & Max Hit the Road, or a deeply introspective narrative like Planescape: Torment.

The thing is - my dad simply didn't understand games. He couldn't conceptualise the fact that they had evolved far beyond the coin-operated Galaga or Pac-Man of the 70s and 80s, and had revolutionised the narrative experience. As much as I tried to communicate the incredible power of games as a uniquely interactive medium, my dad simply couldn't understand, as he was so far removed from even the most remote exposure to the medium.

Dad knew that I loved games, and respected that I saw something in them, but just didn't comprehend it. I had long accepted that it was simply a reality of that generational gap, and I appreciated that dad would listen to me extolling the virtues of games as a valuable art form, even if I knew that he didn't fully appreciate my arguments. Though he mightn't have agreed with my assertions, he had always shown the deepest respect for my convictions.

And so it was, until December 2020. Dad was in his 70s, but his vibrant life had somewhat taken its toll; this Christmas more than any other, I could see the years weighing heavily upon him. As we had so many years before, we shared in an incredible Christmas lunch accompanied by no shortage of wine and, eventually, whisky. Everyone else eventually went to bed, but my dad and I continued to chat long into the evening.

At the time, I had been listening to the Revolutions podcast by Mike Duncan. It is an incredible podcast, and over ten seasons, takes an in-depth look at famous revolutions in history - the English Civil War, the American Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, French Revolution, all the way up to the Russian Revolution. A conversation with my dad eventually meandered into the topic of this podcast, and I shared the insights that Mike Duncan's inimitable style had conveyed so effectively.

We chatted for a while, about history, the Age of Enlightenment, and (at my father's prompting of course) the significant role that the progressive Scots had played in this era. Suddenly, out of nowhere, my dad asked me a question:

"How did you become so interested in history like this?"

I thought about it for a second - why was I so interested in this period of history? The answer leapt into my head - Creative Assembly's Empire: Total War. Of all the games in the Total War franchise, Empire had captured my imagination like no other, and it inspired a deep fascination in the transformative centuries of the 1700s and 1800s.

Of course, as a lifelong gamer, I jumped at the opportunity to explain this to my dad. I told him how the Total War series, and other series like Age of Empires and Paradox grand strategy games, had sowed the seed of curiosity that had driven me to seek more knowledge and understand the history of the world we live in.

For the first time in my life, I saw a spark of sudden comprehension in my father's eyes. Though the rather liberal distribution of whisky clouds his exact words, I can paraphrase how he responded: "Interesting. I never realised games could do that". We were then propelled into a discussion on the nature of games, and how valuable and unique they were as an entertainment medium. Games inspired curiosity, and curiosity is the most critical motivating factor that drives someone to learn. Finally, my dad understood the value I saw in games; I could see the realisation in his eyes.

I have no doubt that a psychologist could have a field day with this - here I was, after so many decades, finally attaining tacit approval and respect from my father for a hobby that I loved, but that he had never understood. But that doesn't matter. This was a special moment with my father on a special day, and after decades he had finally come to understand more about me.

A few months later, I received a phone call from dad, and he informed me in his typical matter-of-fact tone that he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer -a condition that had likely been developing for several months already, including while we sat together over that last Christmas. A few months later, in late May of 2021, he finally passed away.

Games have always been incredibly special to me. I have never experienced anything so emotionally powerful as Planescape: Torment or Red Dead Redemption 2. I have been endlessly inspired by the artistic genius of INSIDE and Fez. I have been transported to vibrant worlds by Baldur's Gate, Disco Elysium and Half-Life.

At the very end, after so many years, my father had finally come to understand something new about me. For so long, games had merely seemed like a distraction from getting my homework done, or from going outside and kicking a ball. But a simple link between a history podcast and Total War had unravelled that bias and led to a deeper understanding that heightened our bond in his final days. Nothing can heal the hole left by that loss, but nothing could be more special than connecting over a personal passion with someone you love.

At SUPERJUMP, I'm honoured to be surrounded by writers who share that passion for this unique medium. I firmly believe games have a power that no other medium can reproduce - the choices are yours, the consequences are yours, and the right game can leave a lasting impact that will define you as a person. Share your gaming experiences, and encourage those around you to take the plunge if they haven't already. The right game can change everything.