Tetris at 40: The Twisting Tale of Its Journey to Handhelds

The most-ported game ever found its way to some very unusual places

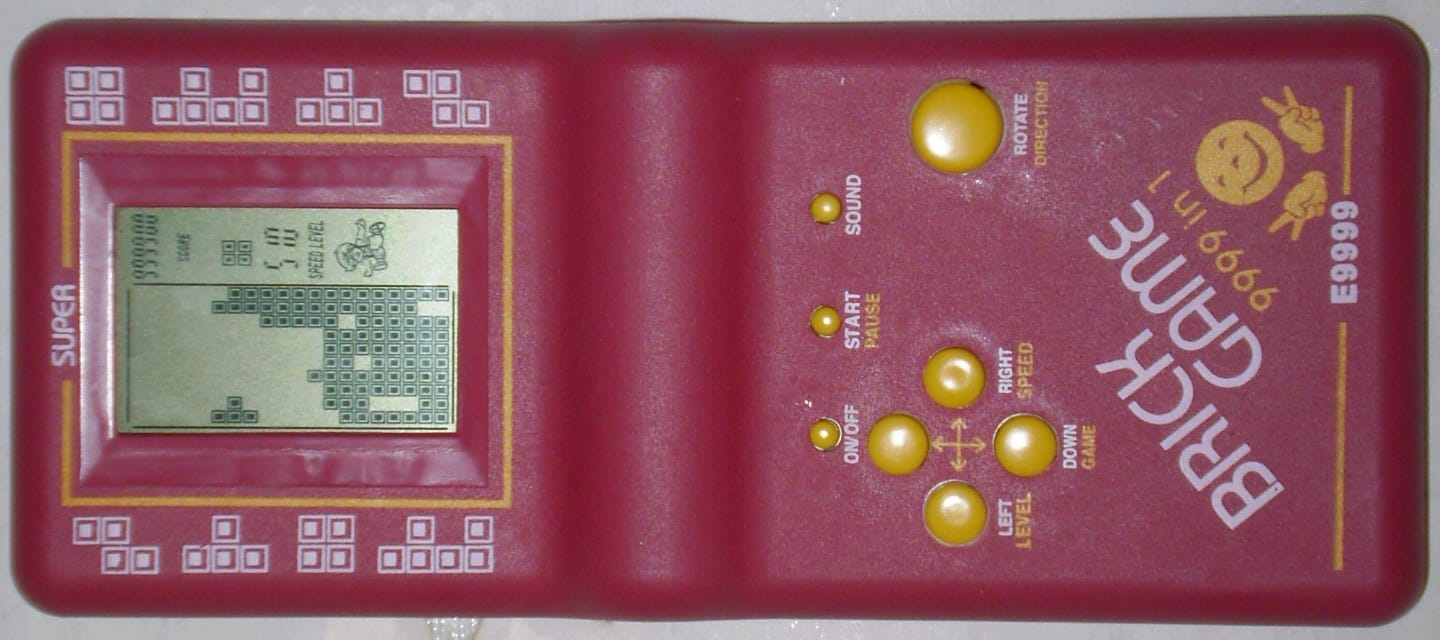

The screen that opened up Tetris to a new group of gamers was that of the handheld. In this area, its success became synonymous with the Nintendo Game Boy. That wasn’t the case everywhere, though. In the developing world, an official Game Boy was out of reach for millions, so some turned to other options, such as the infamous Brick Man console. The torturous route of Tetris’ licensing dance in the 1980s had laid the foundations of this world.

Blocks on a screen

In 1984, when Alexey Pajitnov created a puzzle on an Elektronika 60 computer, there was no way he could’ve known that it would become one of the most famous games of all time. It did soon become apparent at the Soviet research center that it was addictive, though. Two years later, a manager sent it to the Coordination Institute for Computer Sciences in Budapest, where it captured many people’s attention as well.

This is when Robert Stein entered the scene. As an American, he was on the other side of the Cold War divide, but he had caught wind of its popularity in Hungary. He contacted the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. Alexey Pajitnov sent a reply, but somewhere in the Russian-to-English translation process there was an error, which led Stein to believe he had the go-ahead to license Tetris to western companies.

Stein sold the rights to Spectrum Holobyte and its sister company Mirrorsoft. They released the first commercial version, a PC port, in 1988. But the trail didn’t end there though, because Spectrum Holobyte also sold the rights to Atari, who then licensed the Japanese arcade rights to Sega.

Still, the state, not the developer, owned the intellectual rights in the Soviet Union. So, in spring 1988, Stein at last signed an agreement with the state agency that controlled software rights, Elorg. This contract only covered the PC rights, though. The intellectual rights carousel had already spun around a couple of times.

Seated in an audience box

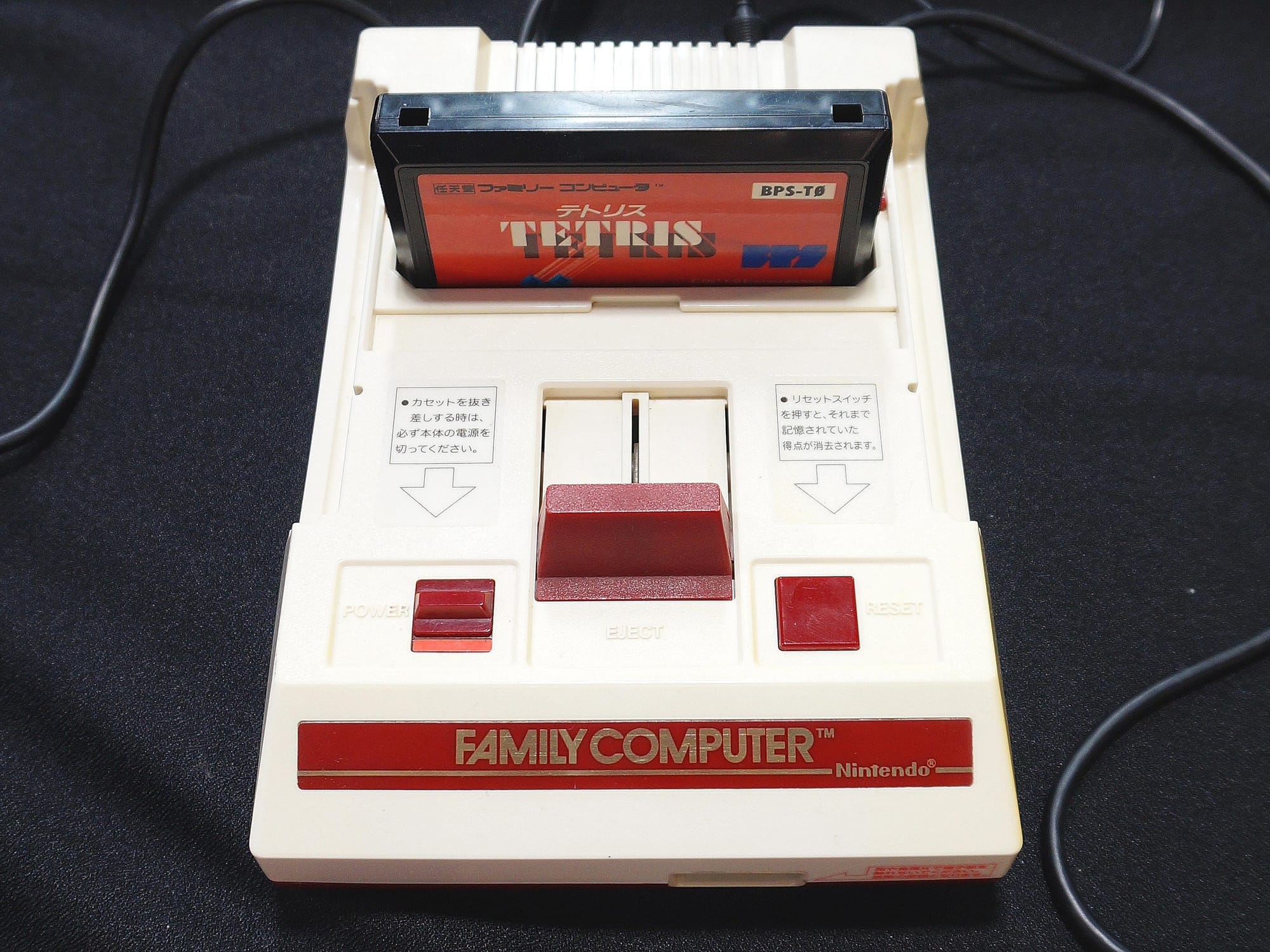

Henk Rogers, the founder of Japan-based Bullet-Proof Software, secured the Japanese rights for the console version of Tetris from Spectrum Holobyte. He loaned massive amounts of money to produce Famicom cartridges, but then found out that the rights were not valid. With his future on the line, he flew to Moscow in 1988 to straighten out the matter.

At the time, Nintendo was looking at Tetris as an addition to its planned handheld console’s software catalogue. Someone offered Nintendo the Tetris rights, but Rogers asked Nintendo to trust him instead.

Nintendo soon flew their representatives to join Rogers in the pivotal Moscow discussions. Elorg, for their part, did not enjoy it when they discovered the scope of the Tetris rights sale on the other side of the Iron Curtain. After a bit of back-and-forth, Henk Rogers struck a deal with Elorg that gave him the console and handheld rights, which he licensed to Nintendo. Robert Stein, on the other hand, could still keep the arcade machine and PC rights.

Tengen, a subsidiary of Atari, ported its parent company’s arcade game to consoles in 1989. This contravened the new rights agreements. In June of that year, Nintendo won a court injunction that barred Tengen from selling more copies of Tetris, forcing them to destroy hundreds of thousands of their cartridges.

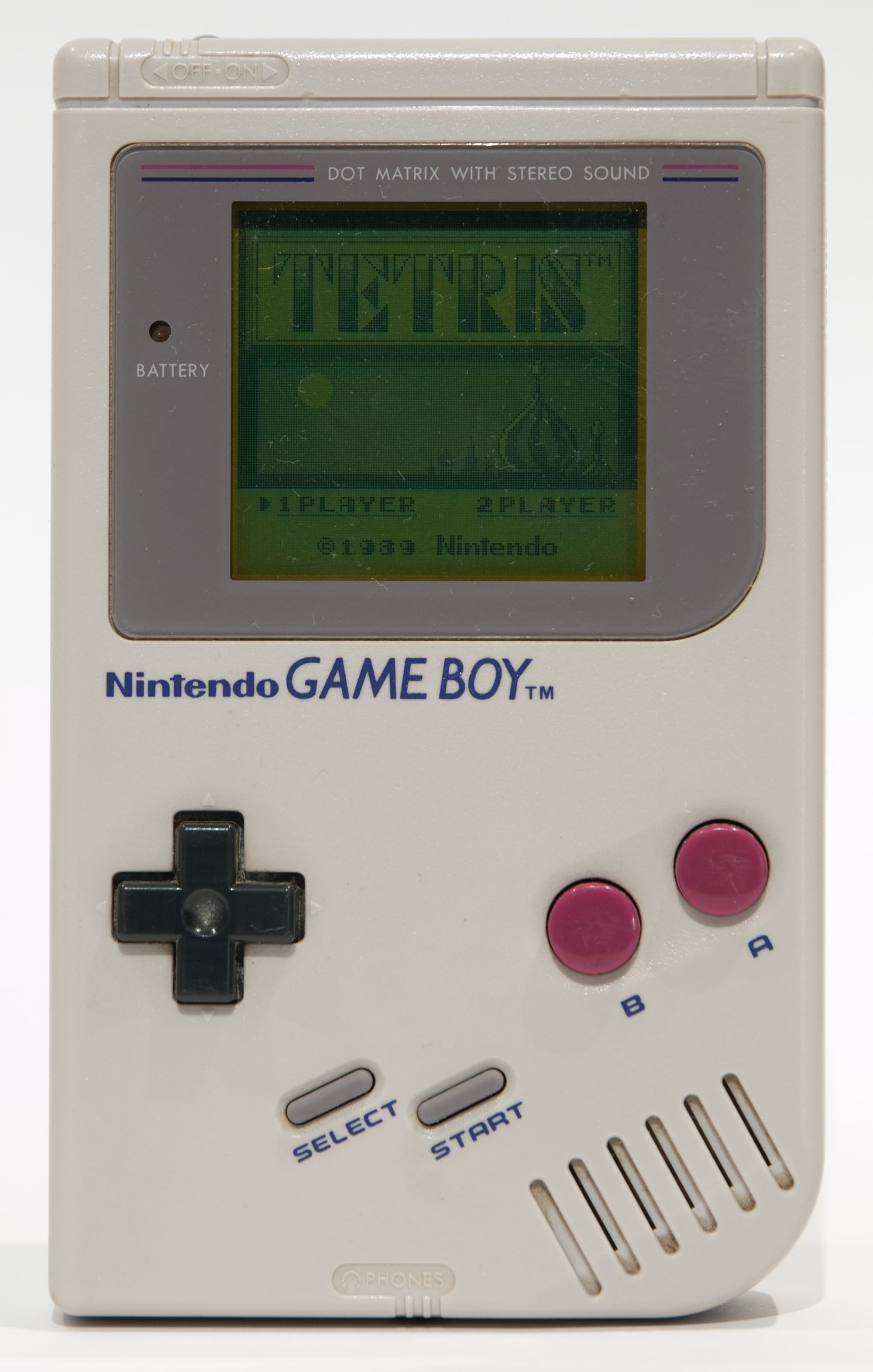

The North American release date of the Game Boy was in late July 1989. What would be its killer app in that market? It was a question that would shape the future of gaming.

Hands on the controls

Henk Rogers advocated for them to bundle Tetris with the Game Boy. He knew its potential. In fact, ever since he first encountered it at a Las Vegas expo, he had become hooked on the game. Convinced, Nintendo agreed to pull the trigger.

The Game Boy craze hit America. Its fuel was Tetris for a long time. In the US alone, Nintendo sold a million Game Boys during its release year, but the demand still far outstripped the supply. Copies of Tetris were an ever-present companion of the console.

Several factors made Tetris perfect for the specific hardware. For one, the graphics comprised of large blocks on a field, which made it legible on the grayscale screen that was not backlit. The input, namely manipulating blocks, also felt natural with the console’s D-pad. There were no complex storylines, characters to remember, or complicated gameplay mechanics. A traveler could play Tetris in short bursts, at appropriate (and inappropriate) times.

The game was such a phenomenon that Richard Haier, of the University of California at Irvine's Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, scanned the brains of Tetris players in 1991 to understand how it influenced humans. The so-called Tetris effect described the way the game trained players how to use their brains. Players entered a state of flow that was addictive and challenging at the same time.

A flight towards developments

All the game’s aspects made it an attractive game for other handhelds, too. Shenzhen Xinfeilong Electronic Factory created variants, reminiscent more of the Game & Watch systems than the Game Boy, with Tetris preinstalled on the systems. The unlicensed Chinese and Russian consoles bore the name Brick Game, so as not to attract unwanted legal attention. These devices brought the game to millions more players during the 1990s.

In 1996, Henk Rogers and Alexey Pajitnov founded the Tetris Company to manage the rights of the game. The proliferation of unlicensed Brick Game variants waned over time as litigation and the rise of cell phone games took its toll on their popularity. Still, a quick investigation online shows that companies still produce them decades later to satisfy the nostalgia of gamers.

In fact, the Tetris Company itself partnered with 7-Eleven to produce a licensed Tetris handheld for the 40th anniversary of the game in 2024. In the same year, Tetris Forever will also celebrate the title’s rich legacy. Few games have stood the test of time quite like it. Tetris’ path to fame was full of detours, but it doesn’t seem like we will tire of those peculiar, misshapen blocks anytime soon.