SUPERJUMP PVP #2: The Hero's Journey in RPGs

Analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of RPGs featuring the "hero's journey"

If we were to list the most recurrent features in RPG design or even video games in general, certainly a “hero’s journey” (monomyth) narrative design would be among them. In fact, this type of narrative proposal is common in various other media, including classic plays, superhero comics, popular books, and many Hollywood films. In the second entry of the SUPERJUMP PVP feature, Brandon R. Chinn will argue for the “glass half full” perspective on this matter, whereas Vitor M. Costa will delve into the “glass half empty” analysis.

Before we look at both sides of this story, we need to establish our terminology. We will use the RPG concept as defined in What is the Difference Between Western and Eastern RPGs? (SUPERJUMP, 2021):

An electronic game is of the RPG genre (a Role-Playing Video Game) when it emphasizes the control and internal economy of an evolving character or group of characters (a party), in some world designed for narrative and exploration purposes.*

Finally, "the hero's journey" or "monomyth" refers to a narrative formula that Joseph Campbell described in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949). It focuses on a hero with special potential whose capabilities are underestimated, but who overcomes challenges, conquers the confidence of others, and faces and avoids an imminent tragedy in their world. With the diagram below, you can gain a sense of how this concept works.

Glass Half Full

by Brandon R. Chinn

- The hero’s journey allows the audience to resonate with an established storytelling framework.

- The hero’s journey accomplishes the traditional “adventure” experience that satisfies the audience's expectations.

- One can replicate the hero's journey in both large and small scopes while still having creative storytelling freedoms.

There may not be a single crutch more commonly used in fantasy and science fiction than Joseph Campbell’s “hero’s journey.” As helpful as it is dismissive, Campbell’s reductionist take on mythological binaries is not without merit. One enormous criticism of Campbell’s infamous idea governing mythology and fantastical tales is that it lacks nuance, flattening the complexities of stories to make them fit agendas. Nowadays, popular examples like Marvel films and television commercials frequently employ the hero’s journey archetype; however, the overly simplified notion of “forcing the hero to climb a tree, throwing stones at them while they’re up there, and then making them climb down” is inherently reductionist.

It's unclear if the hero's journey is a narrative pattern or if it's popular because it's easy to follow. Video game developers use the hero's journey because it requires little establishment. RPGs like Dark Souls and Final Fantasy have successfully applied Campbell's philosophies to immediately ground the player. Although some may criticize the hero's journey for being formulaic, it still serves as a great template to start any story.

From left to right: The heroes of Marvel's Guardians of the Galaxy, Final Fantasy VIII, and Dark Souls. Sources: IMDB / wccftech / gamerview / Square Enix / FromSoftware / Bandai Namco Entertainment.

Analyzing video games through a literary lens can prove challenging because of their departure from conventions. Establishing the genres that are now considered a given has taken video games years, and even when they fall under a specific genre, it remains difficult to accurately measure them.

While both Dark Souls and Final Fantasy fall under the RPG category, a substantial design gap sets them apart. Even within the realm of Final Fantasy, games like Stranger of Paradise differ significantly from World of Final Fantasy. When the hero’s journey is used as this contemporary template, audiences can attach themselves to a perceived genre and not feel disoriented by whatever comes next, regardless of creativity. Though it is largely reductionist, any RPG can be critiqued by its pieces, and nearly every RPG in existence follows Campbell’s monomyth.

When discussing the advantages of the monomyth, we circle back to its establishment and the influence of audience engagement and enjoyment through preconceived notions. Fantasy and science fiction have largely followed the hero’s journey, not solely because of Campbell’s influence. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, for instance, served as a template for fantasy over decades, seamlessly blending the familiarity of established mythology with the contemporary flair of original fiction.

From left to right: The protagonists of Stranger of Paradise: Final Fantasy Origin, World of Final Fantasy and The Lord of the Rings. Sources: gamingtrend / pleno.news / gamerstyle / Square Enix / Warner Bros.

The hero’s journey inherently embraces individualism, aligning with societies that uphold self-importance. Although RPGs frequently involve groups of characters, they give the protagonist elevated narrative weight. In titles like Final Fantasy VIII, the player can only see the protagonist’s thoughts; Chrono Trigger’s conclusions hinge on the protagonist’s survival; and in Undertale, immense importance is given to the relationships between secondary characters and the silent protagonist.

Particularly in Western society, these individualistic narratives resonate with people who find their place within the monomyth, relishing their role as the “special” one within the collective. Even in RPGs with expansive casts, such as Xenogears or Xenoblade, there’s a tendency to focus on that unique element destined to awaken within the protagonist’s heart or being. While this plot twist is a predictable feature of RPGs, the genre actively explores the myriad ways we can examine mystical existentialism, often achieving highly effective results.

From left to right: Reunion ending and The Apocalypse (Bad Ending); Pacifist ending and Genocide ending. Sources: chronocompendium / arrpeegeez / aminoapps / Square Enix / Toby Fox.

While the hero’s journey framework might draw criticism for how often it is used and its susceptibility to the overuse of familiar tropes, it offers writers a toolbox to build narratives that deliver impactful emotional moments without leading the audience astray. Since RPGs can struggle with balancing gameplay and narrative, the hero’s journey accomplishes substantial literary heavy lifting.

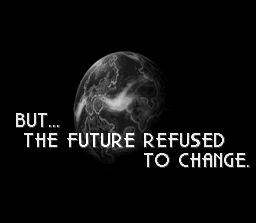

Recent RPGs like Final Fantasy XV have relied on the framework of the monomyth transparently and resonated with casual audiences uncertain of how to enter a series. Even if the traditional hero’s journey is lacking nuance, growth, and originality, the easily recognizable framework can provide an audience with what they expect while also leaving room for more creative aspects. Furthermore, experienced developers have utilized Campbell’s monomyth to challenge and transcend genre and medium expectations, such as Yoko Taro’s NieR games, Final Fantasy VI, or Persona 3.

From left to right: The protagonists of Final Fantasy XV; Persona 3 Portable (male and female versions of the protagonist). Sources: SUPERJUMP / win.gg / Square Enix / Atlus / SEGA.

Glass Half Empty

by Vitor M. Costa

- The hero's journey overvalues the exceptional and the extraordinary over the usual and ordinary experience (which is a much more concrete and "real" experience);

- The hero's journey tends to give easy individual solutions to complex problems that should plausibly be solved socially and gradually;

- The hero's journey in general is based on a very naive distinction of good vs. evil, which rarely makes for adequate solutions to social and metaphysical problems or for well-written villains.

My more general criticism of the hero’s journey approach to fictional works is its emphasis on the extraordinary. While it is difficult to assign a clear and non-trivial definition to the hero’s journey, at its core, this structure involves the transition from the ordinary world to an extraordinary world. It is because of this second world that the protagonist is a hero.

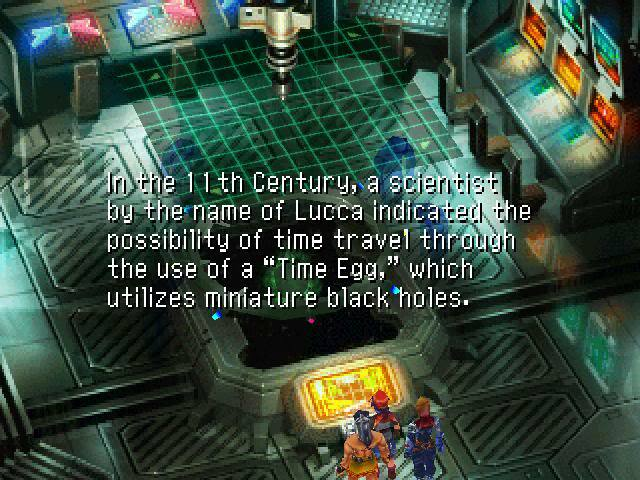

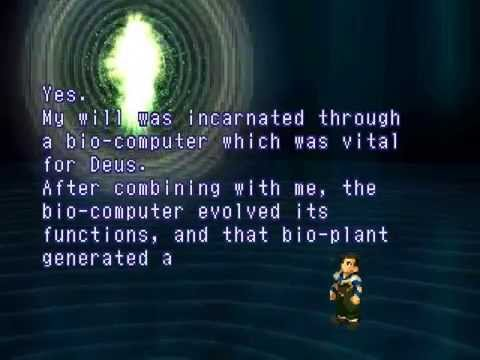

That there is someone extraordinarily special to save the ordinary world can contain interesting abstract concepts (for example, in Chrono Cross and Xenogears), but they are rarely effective for us to reflect on the actual problems in our life in a more concrete way.

Scenes that introduce abstract concepts into the plots of Chrono Cross (left) and Xenogears (right). Sources: SUPERJUMP / Rundas (via YouTube) / Square Enix.

I believe that much like contemporary literature has rekindled an appreciation of concrete life, the ordinary, and the everyday, showcased through diverse styles (as seen in the works of Ernest Hemingway and Charles Bukowski), some RPG developers are infusing this into their games.

"When writing a novel a writer should create living people; people not characters. A character is a caricature."

— Ernest Hemingway (Death in the Afternoon, 1932)

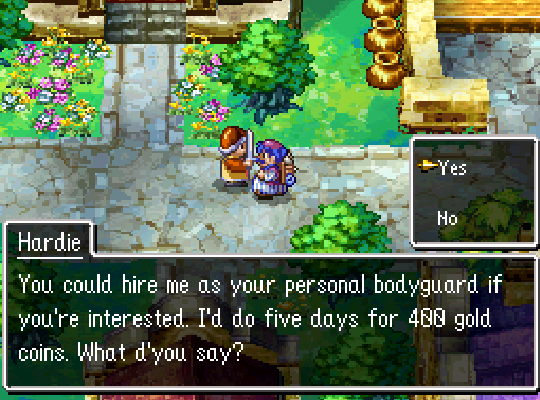

A good example is Chapter 3 of Dragon Quest IV in which we have Torneko as the protagonist. He is not a hero but an extremely weak merchant (in general, we just try to run away when a battle starts) who has the dream of having his own store with his family in another city. In a darker and more complex proposal, we have the case of Disco Elysium. In this game, we play as a drunk detective attempting to solve a murder case in a city where its inhabitants do not trust one another and are divided by extremist political ideologies.

From left to right: Torneko hiring a bodyguard in Dragon Quest IV; the protagonist of Disco Elysium. Sources: almarsguides / Steam / Square Enix / ZA/UM.

I’ve noticed that narrative arguments like these (which are common in other media) are extremely rare in RPGs because of the popularity of the hero’s journey. While the heroism of someone destined to save the world can be used as a symbol for many things, it rarely reflects how problems in the ordinary world can be solved realistically and also hardly capture the “magic” of the real.

Another issue (as my friend Brandon anticipated) that demands attention is the challenge of individualism. I feel that individualism often becomes an overused element within the hero’s journey framework in video games, undermining the believability of their plots.

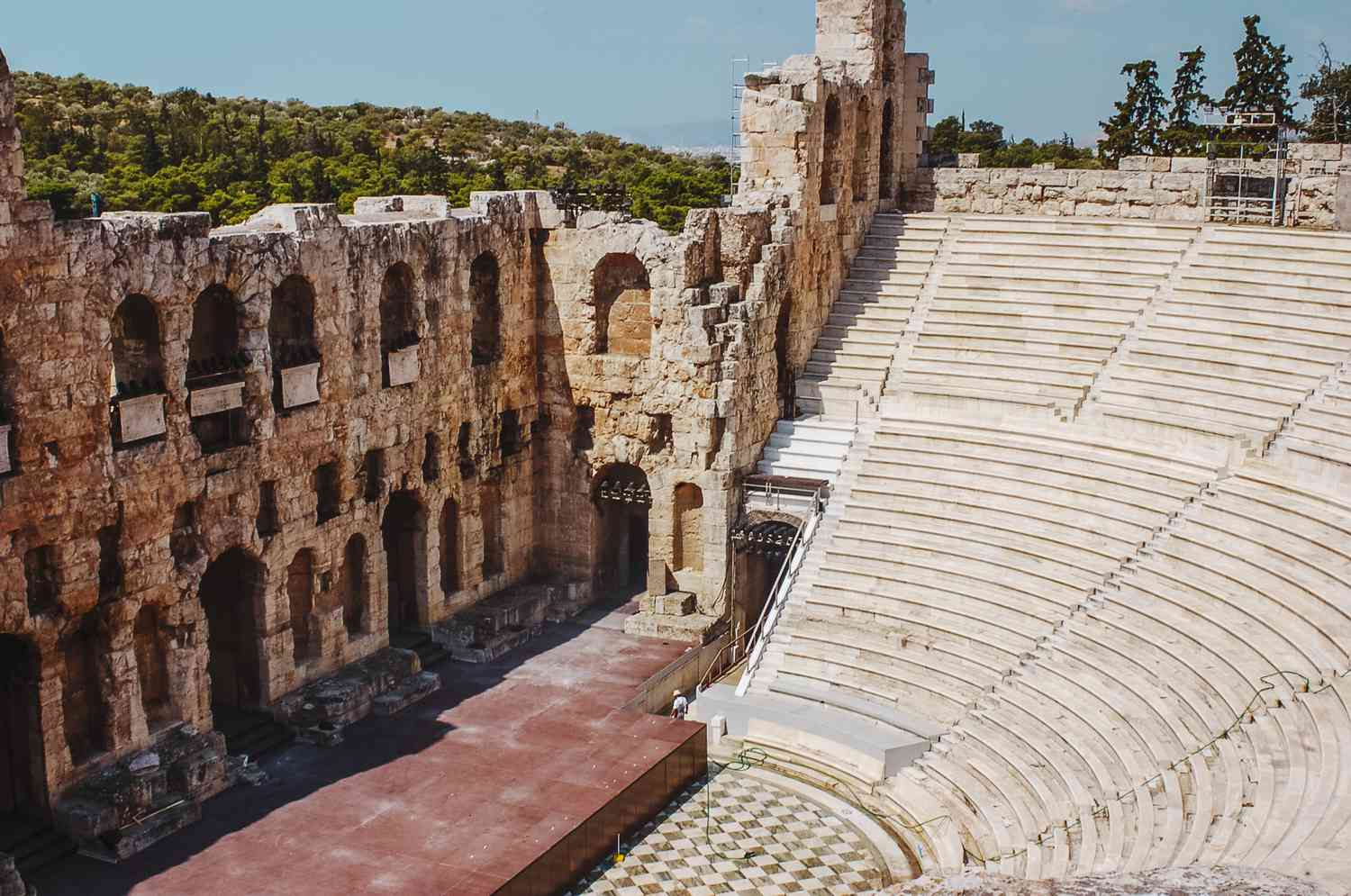

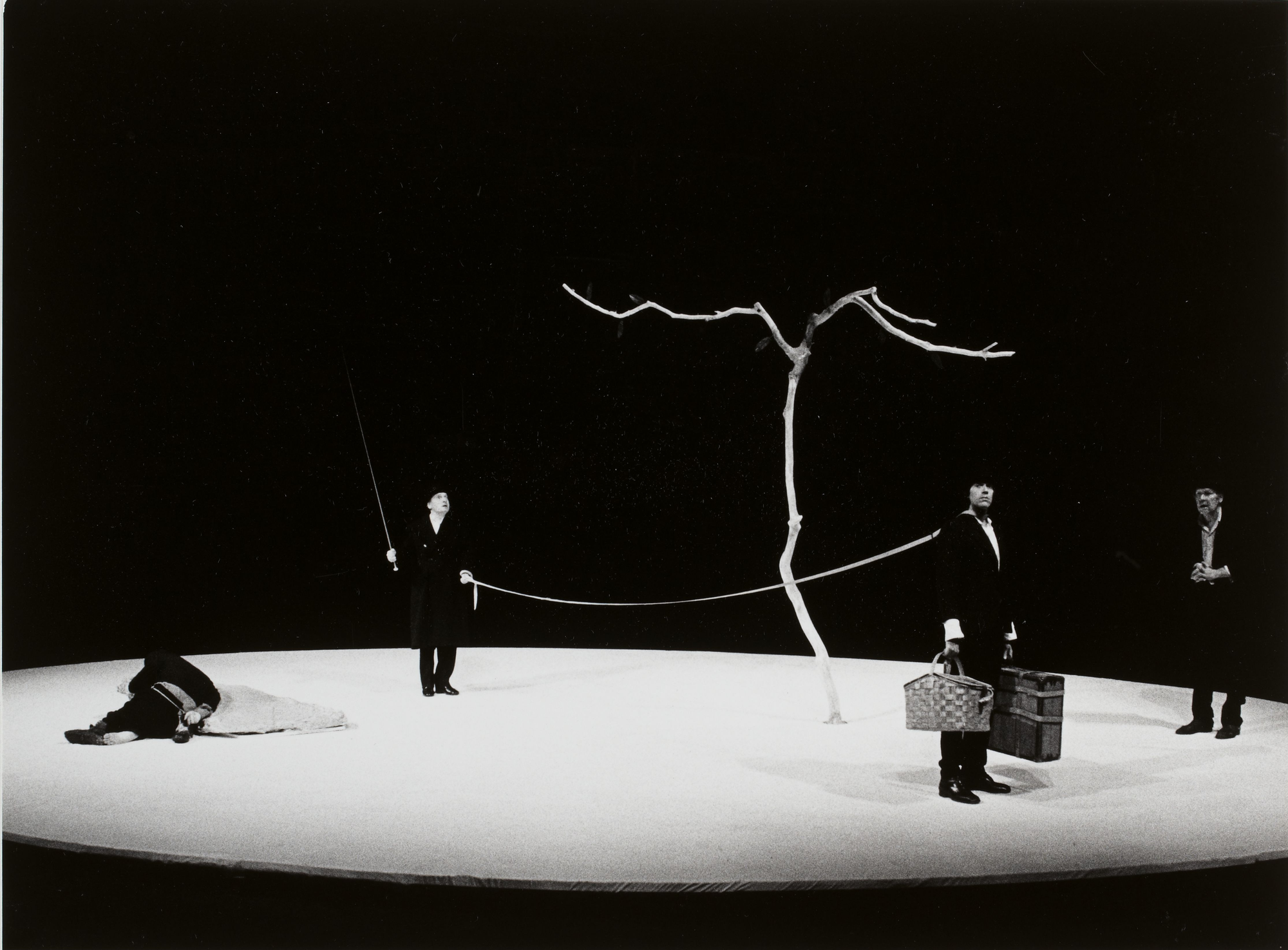

From an Aristotelian standpoint, a good narrative should possess an element of “verisimilitude” —the quality of being plausible or similar to real things we know. Without this quality, the narrative’s credibility can be compromised, affecting both rational and emotional engagement. Figures like Samuel Beckett from the Theater of the Absurd and unconventional game directors like Goichi “Suda51” Suda might not fully agree with Aristotle’s perspective. However, verisimilitude remains a crucial factor in most fiction, whether within the realm of video games or beyond. This is true in science fiction or political storylines. However, in terms of narrative design, the hero’s journey can create challenges within this aspect.

From left to right: The Odeon of Herodes Atticus (greek theater); "Waiting for Godot" (by Samuel Beckett), a herald for the Theatre of the Absurd. Sources: tripsavvy / Taylor McIntyre

The hero's journey is conceptually present in myths from different cultures and times that lack the modern concept of fantasy or even fiction. However, with video games influenced by modern Western individualism highly valued by romanticism and liberalism, this aspect also is incorporated into video game fiction and finds a powerful catalyst in the concept of the hero’s journey.

With RPGs, I think that heroic individualism undermines the verisimilitude of plots mainly in two aspects: protagonist performance and social phenomena. Let’s start with the protagonism.

Evidently, that a fiction has a protagonist is not a problem, but it can become a problem when the protagonist seems to be conveniently very lucky or powerful arbitrarily, and normally the heroes of RPGs have these two characteristics. For example: in Mass Effect, you and your party are supposed to be skilled humans and aliens, but you’re still ordinary beings who shouldn’t be that much more powerful or resilient than your enemies. However, the narrative is written in such a way that on your adventure you kill thousands of enemies with skills close to or superior to yours.

Thus, although sometimes there are occasional sacrifices (especially at the end), you feel like a superhero rather than someone on an extremely challenging and risky adventure. This problem is even more clear in cases of RPGs with background political plots, as you often feel that instead of being a battle between nations, it is a battle between a dumb army against a small group of superheroes.

Mass Effect 2; Dragon Age Inquisition. Sources: games.mail.ru / Steam / BioWare / EA.

The excess of individualism often makes some social phenomena artificial and abrupt when, instead, they should have been produced collectively and gradually. For example, we often find a scientist who is practically alone and in a short time makes impressive scientific and technological achievements, when this would only be plausible over a long time and with the help of many scientists. Even in cases of great geniuses of theoretical physics, like Albert Einstein, it takes time and a solid scientific community to prove their theories or to make their concepts useful in technology.

Something analogous happens with kings who suddenly save kingdoms from misery and generals who act as a one-man army. These script artificialities caused by excessive individualism may seem harmless, but when they are frequent, they undermine the immersion of role-playing and become a sign of a lack of creativity, depth, and subtlety in the narrative design.

Finally, something also needs to be said about the simplicity of the Manichaean good-evil argument that is so frequent in the hero's journey in RPGs. I saved this topic for last because I don't think this aspect is intrinsic to the hero's journey. In most mythologies, there is no good-evil dichotomy, but we can say that there are heroes, in some sense.

Just as liberalism and romanticism made heroes individualistic, Western Judeo-Christian influence reimagines the hero’s journeys in such a way that the difference between good and evil is explicitly distinct. Of course, the good-evil duality feature can be used for critical narrative arguments or even other interesting purposes, but most of the time this dichotomy only results in caricatured villains and heroes who can kill their enemies without mercy.

The Dragon Quest series provides the most iconic example of this phenomenon in RPGs, where there is a distinct contrast between the overtly labeled "hero" and some plainly evil main villain. However, it’s important to recognize that this duality is present in the vast majority of RPGs, often in less overt ways but bearing striking similarities in terms of vices and limitations.

The good-evil duality is not always a bad thing, as sometimes we see villains who have unique and captivating personalities, besides playing an important role in the plot's development (and not just at the end); a good example is Kefka from Final Fantasy VI, but cases like these are exceptions. The narrative structure of the hero’s journey in our modern Western tradition offers us simple villains and superficial resolutions to social and metaphysical problems in nations, ecosystems, and world-building.

Final Thoughts

by Brandon R. Chinn

While the concept of the hero can serve a narrative and material purpose in RPGs, I think it’s especially important to remain wary of its use. The protagonist certainly exists as a stand-in for the player, even if the player themselves doesn’t agree with the philosophical ambitions of the hero, but they should mirror the individuals surrounding them rather than being a singular spearhead.

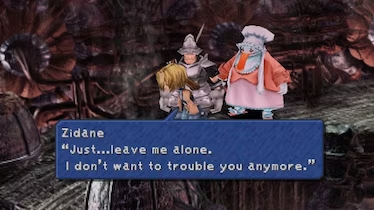

In the most impactful RPGs, the true hero’s journey revolves around growth, change, and camaraderie. If the protagonist is the same at the end of the story as the beginning, there was little meaningful reason for the adventure at all. Games with powerful moments of existential crisis for the hero, such as Final Fantasy IX or Xenoblade Chronicles 3, hammer home their points when the protagonist is allowed to take a beat and reflect on the myriad opinions of their party.

All fiction is more or less a reflection of its time, and we live in an era where hero characters are massively popular (and the ensemble casts less so). Heroism conveys purpose, which conveys meaning, even if this standard isn’t realistic. A good hero exists to uplift those that surround them; in contrast, a negative or useless hero becomes an ego-centric, self-centered crutch.

From left to right: Noah (the protagonist of Xenoblade Chronicles 3) and Zidane (the protagonist of Final Fantasy IX). Sources: PhilUP Clips (via YouTube) / Inverse / Nintendo / Square Enix.

by Vitor M. Costa

Both in real life and in fictional worlds, I think we should be critical and skeptical of so-called “heroes”, especially in a political context.

The interpretation of a fiction affects our reality just as our reality affects our interpretation of a fictional world. In this way, I think that good fictional representations are representations that make us reflect either on fiction or on reality in a profound way or innovatively or both. When reflection is profound, we learn more about reality from fiction. When reflection is innovative, we learn more about ourselves (about our way of seeing reality and fiction).

I think that heroism rarely contributes to profound or innovative reflections. On the contrary, it serves as a simplistic and generic element. On the other hand, the concept of “hero” can often be used in a deconstructive way (as is often the case in Yoko Taro’s RPGs), and I think this is the main positive point of his or her journey. To sum up my point with a familiar metaphor from Ludwig Wittgenstein (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, proposition 6.54): "The hero’s journey is like a ladder that we use to climb, but then throw away when we reach a place from which we need not return."