Signalis Review

Deeper into the abyss

Misery rests at the bottom of most great mysteries.

Though our curiosities are oftentimes unquenchable, there is nothing to stop us from reaching for the unknown. To peel back the layers and step into worn footsteps that have been trodden and stained by blood, there can be no happiness there. Still, we move forward because there are no other options. We have to know.

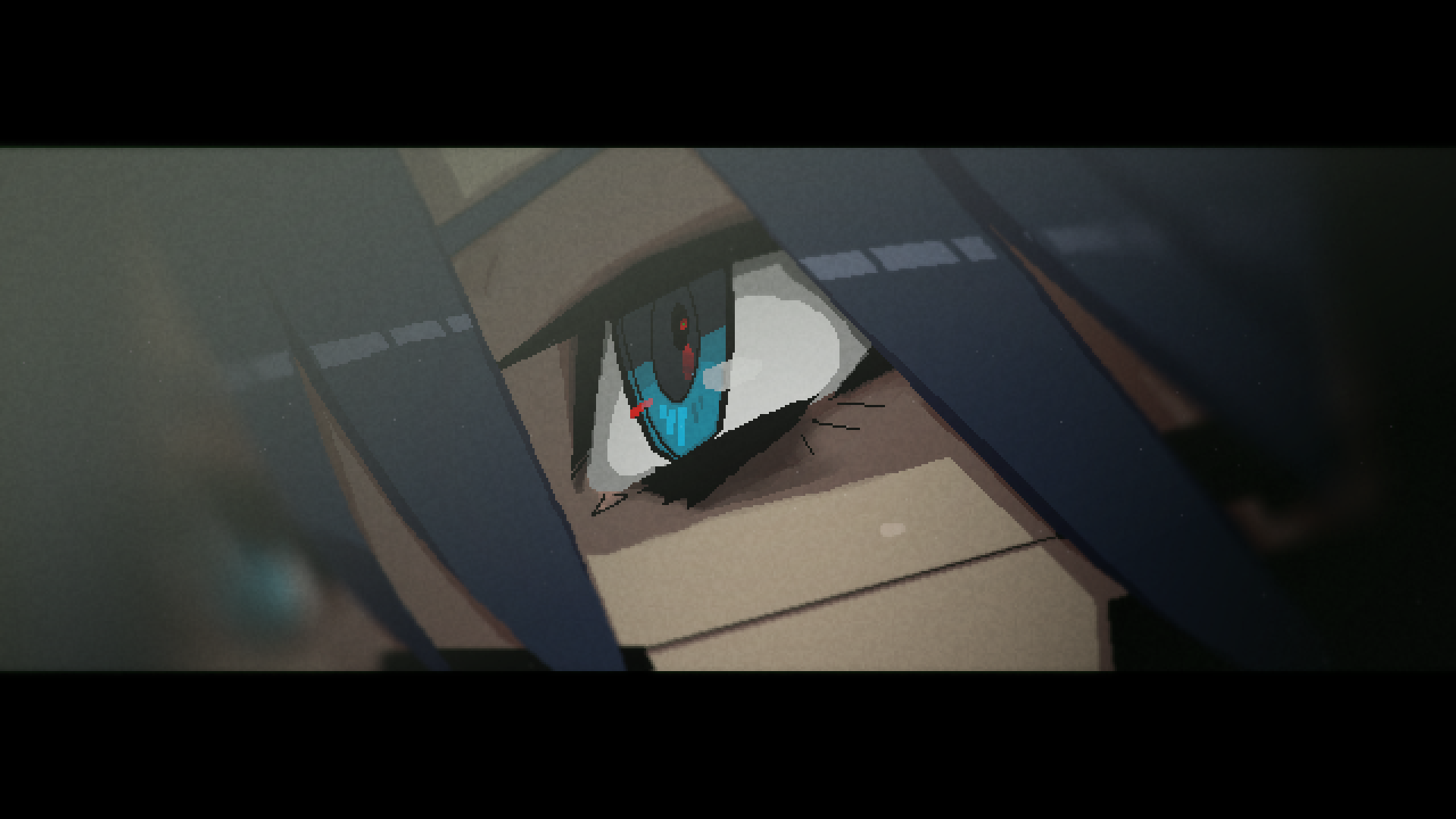

In Signalis, crafted by Yuri Stern and Barbara Wittmann of rose-engine, "Gaze long into the abyss" is granted a textured and emotional meaning. We are given little in the way of context as the game begins, the player in control of a lonely robot that is attempting to restart a downed craft. The spaceship is littered with spectacle—we use tape to piece together a key card, and flip over the back of a polaroid to reveal an important computer code. It's here that the fragments of Signalis reveal themselves: this is the game in the style of classic survival classic horror, and one of few indie horror titles that can hold a candle to the legacy of Silent Hill.

Signalis is something different.

Remember Our Promise

"Great holes secretly are digged where earth's pores ought to suffice."

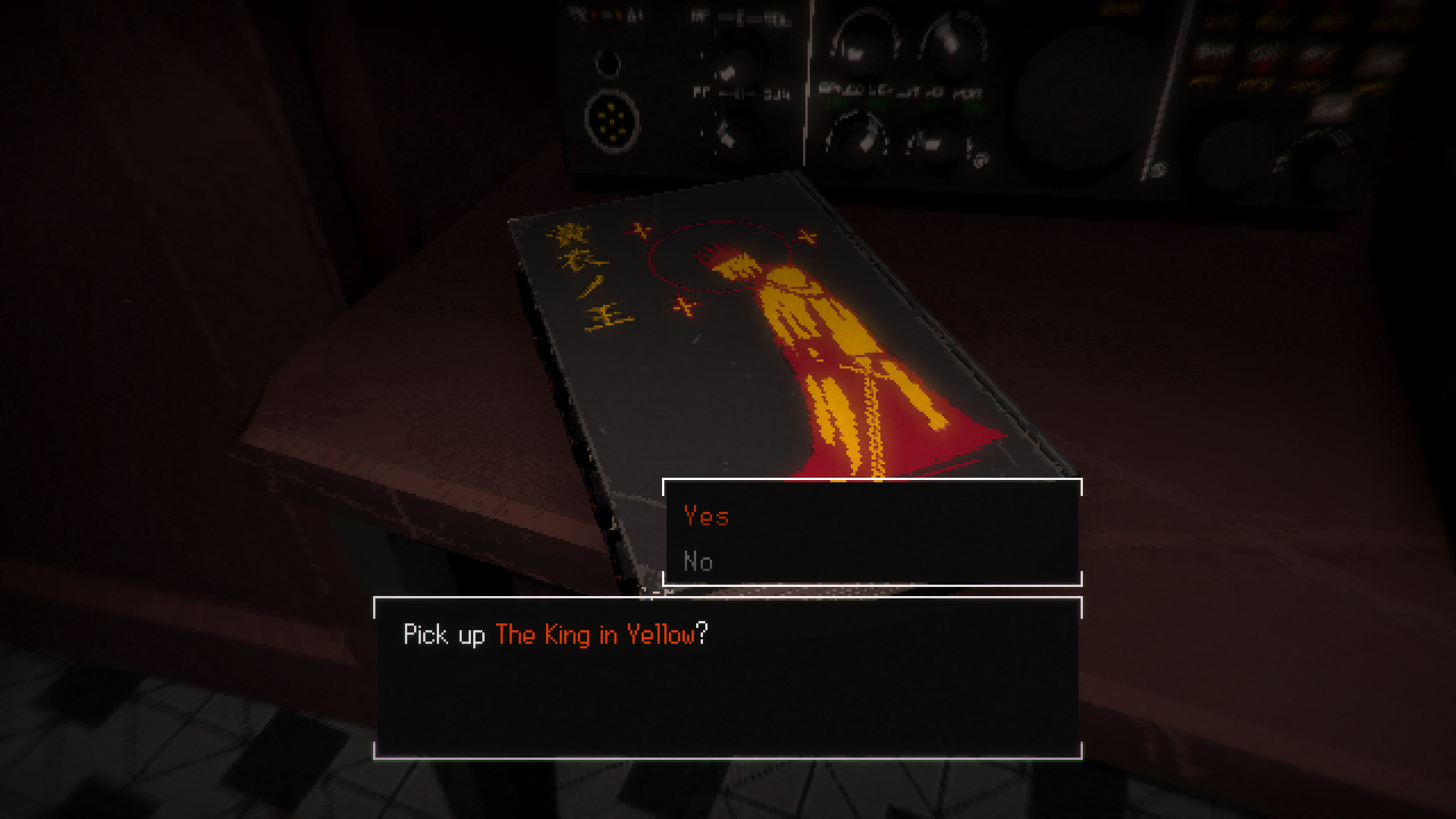

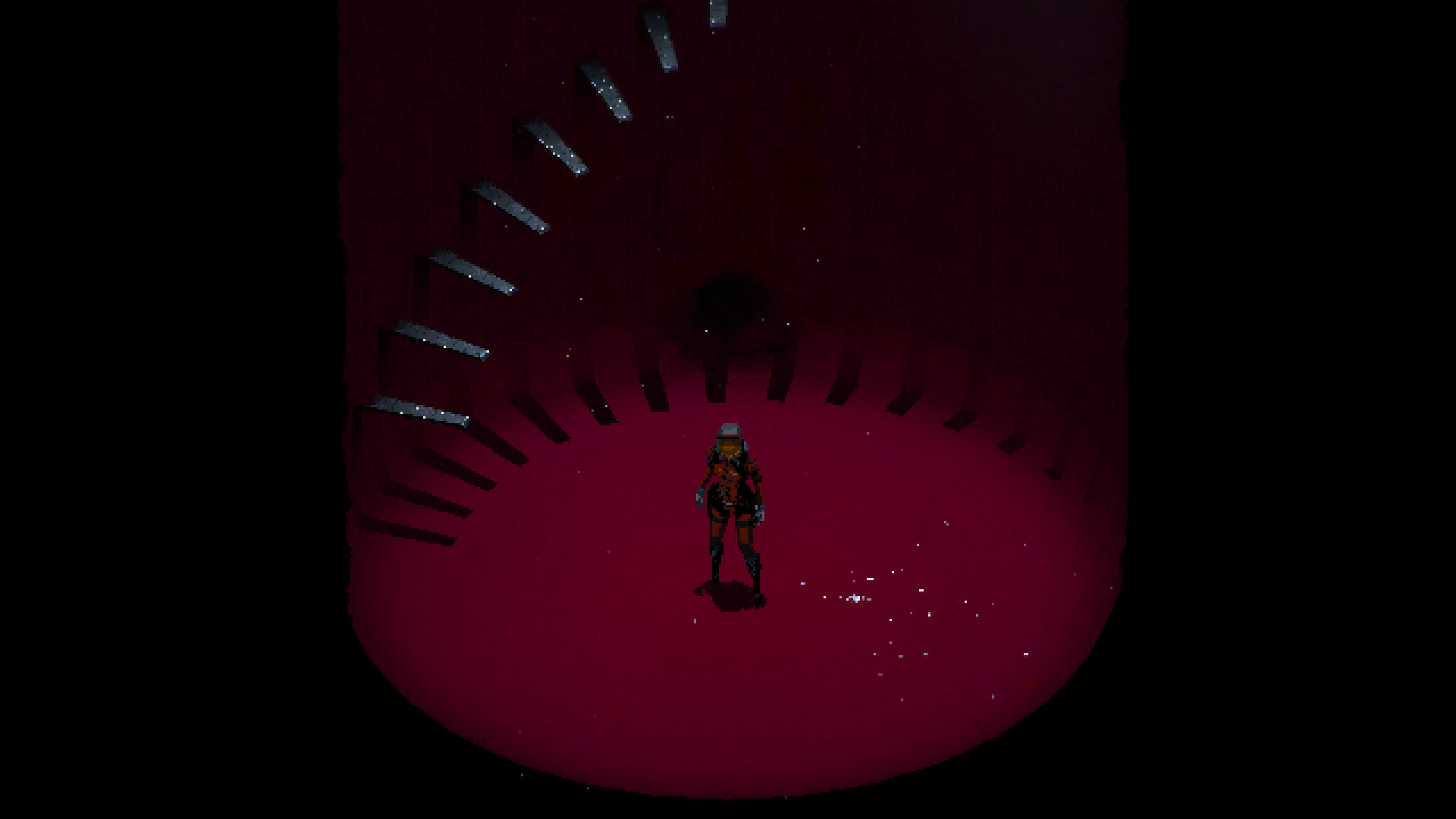

Signalis is a game of holes. Of descent. Of discovering the very boundary of space and moving beyond that to find the blackened detritus behind it. As our robot abandons the safety of a downed ship and braves the cold harshness of an unfamiliar planet, the only respite discovered is a yawning hole in the ground. Upon descent, she moves beyond conveniently alien architecture to step into a well of blood. Signalis transitions into a first-person perspective, and what lies beyond yet another hole in reality is a room containing a single book, a copy of The King In Yellow. The screen flashes red, and through CRT fuzz a quote becomes unmissably readable.

The whole quote, from H.P. Lovecraft's The Festival, reads:

"Great holes secretly are digged where earth's pores ought to suffice, and things have learnt to walk that ought to crawl."

Long has humanity feared the simulacrum, while universally granting it power. Signalis is a game that explores the nascent humanity of inhuman things, objects that bear the physical features and emotional depth of young women. On an absurd planet evocative of Stanisław Lem's Solaris, we are granted a view of the fallout of replicants. We are in the future, and also removed from it—planetoids and systems are being conquered one by one under a fascist regime that employs beautifully deadly soldiers. We control one of those soldiers, "Elster," an LSTR Replika unit devised by the militant nation of Eusan. While Elster herself operates as an individual, she is truly a replica, a simulacrum of her host—all Eusan soldiers are conscious copies of their original base human. They have likes and dislikes. To a certain degree, they have agency over their actions. But each Replika unit is also a slave to a neural pattern that they cannot discern nor understand, fettered to emotions from a past that no longer exists.

Like much of the survival horror genre, motivation in Signalis is guided by a single question: What Happened? Elster's fractured memories and emotional fragility are made raw upon her descent through a facility that feels as though it does not owe allegiance to time or space. As with Silent Hill, the place we explore in Signalis is divorced from its anchored reality. The physicality present in Signalis fades away as we are presented with the harsh meat of its dominion, that something has gone terribly wrong. At this point in the game, it would be difficult to assure the player that they are engaging in a love story, or that Elster's descent into a red-and-black hell is one of the most humanist stories delivered by video games this year. At the time of this writing, I am still piecing together the puzzle of Signalis, but it is worth every single shred of its nonlinear design. If we are truly engaged in a new "vibes only" era of storytelling, Signalis jumps into this service with both feet.

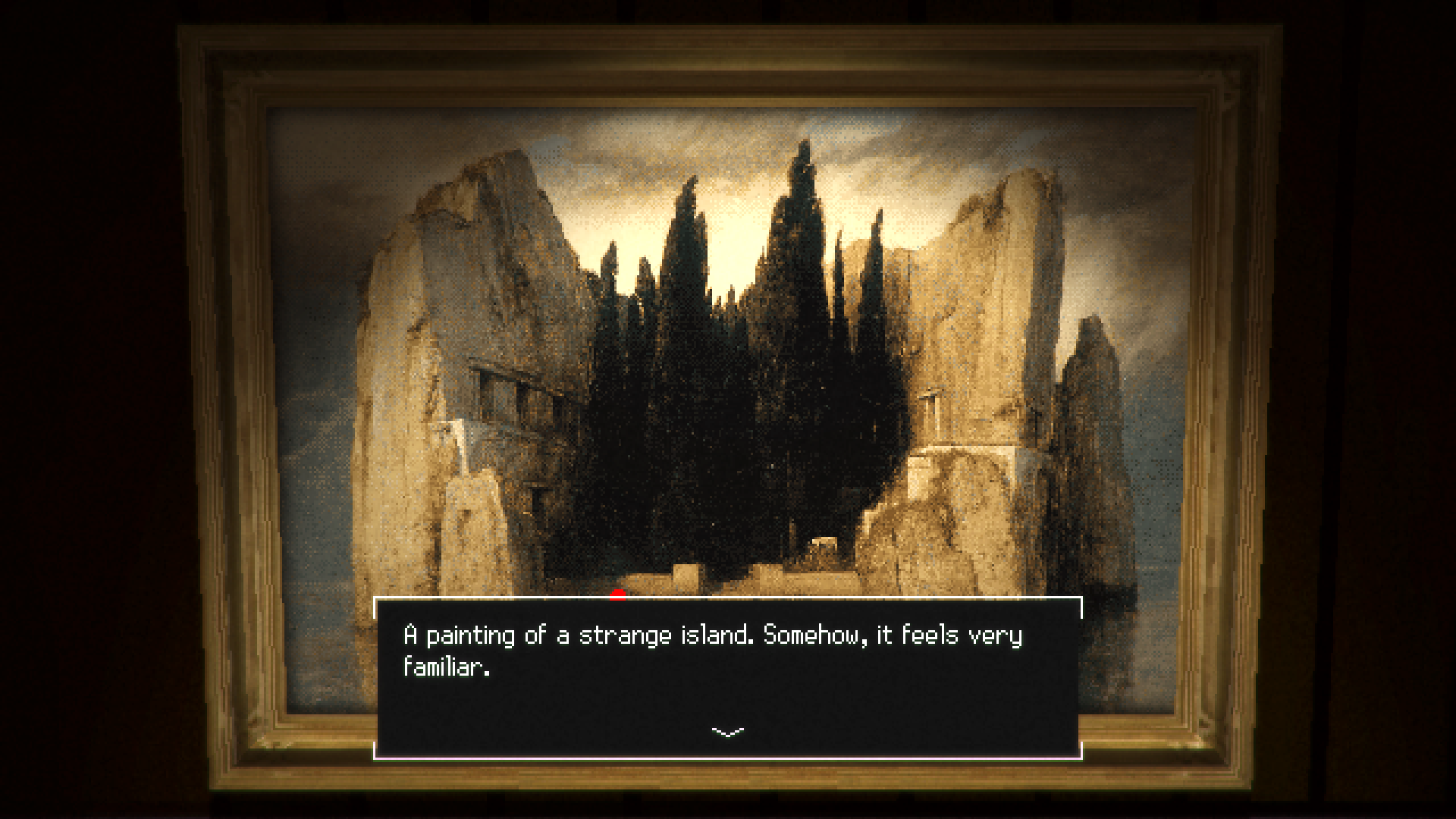

A Sea of Flesh

While most of the game adheres to dream logic, and areas are stitched together by memories and remembrance, the straightforward story is one of desperation. Elster is looking for someone, and along the way comes face to face with the evils wrought across the stars by the Eusan nation. Other Replika units have been corrupted by some sort of disease, transforming them into defiled bodies of walking flesh. It is presumed that whatever has happened to Elster has damaged her ability to perceive reality in its linear state—we the player are subject to out-of-context scenes, looping areas, and disintegrating motives. Signalis uses its first-person perspective liberally, taking control from the third-person perspective and planting the player in scenes inspired by classic paintings such as Arnold Böcklin's Isle of the Dead. Signalis' literary approach to survival horror is where it gets its cleverness, and it is in this design that such a small indie offering feels like it belongs on the shelf between Resident Evil and Silent Hill.

The gameplay in Signalis is straightforward and addictive. Early on in the story, a scrap of lore informs us that the Replika units are not allowed much carrying capacity to make them work more efficiently. With only six total slots and no upgrades, the loop of finding key items, juggling weapons, and depositing items into safety boxes becomes a puzzle of its own. The game is replete with its own brand of puzzles, nearly all of them exceedingly clever. It's also not a lengthy experience—the first play-through of Signalis should only take about 8 hours, which is fortunate for those who want to experience the story multiple times or conquer its rather obtuse ending paths. Signalis feels like a game within a game within a game and is the sort of deep dive experience that internet sleuths have not had since P.T.

Much of Signalis plays out in the third person, where you control Elster as you explore rooms, gather items, read scraps of paper and fight enemies. Bosses are few and far between, and I was able to finish the game with the bulk of my weapons and ammunition intact. Survival horror veterans will be comfortable with this experience, though the back-and-forth of depositing items and finding a key for a key for a key might be off-putting to those fresh in the genre. Even if you might find its general feel abrasive, Signalis is more than worth the time spent. I cannot recall the last time I played a video game that so completely absorbed my mind - I've rarely stopped thinking about it since finishing my first playthrough weeks ago. As of this writing, I'm playing through it again just so my partner can experience this disturbing game secondhand.

We Will Become One

"Something old, far older than humanity, sleeps deep below the ground."

Signalis is not structured like a traditional narrative. It wants you to think, ponder, and ask questions. After the credits roll (and not those ones...you'll see what I mean) its scenes unravel to reveal the ugliness beneath. Signalis is a game about identity, about anxiety, about mutilation, about loss. As Elster bravely fronts this abyss, she resists the descent into madness that takes hold of the surviving Replika units. Whatever the Eusan nation has done here is worse than imaginable—this is the sort of psychological horror that makes its own truth as it trudges along.

What stands out most about Signalis is its bleak beauty. Beyond its gorgeous Playstation pixel aesthetic and late 90s anime-inspired art, it's a game that wants to be free of genre, expectation, or definition. I've seen many people herald Signalis as one of the best games of 2022 entirely because of how unexpected it feels, even when it bears uncanny familiarity to long-ago experiences. Yes, it is obvious enough to label it a spiritual successor to Silent Hill 2 in everything but the brand, but it's more than that. Rose-engine has worked hard to craft a compelling narrative and exquisitely deranged vibes of a kind I have not experienced since playing through Ada Rook's Fallow. It is because Signalis evokes a depth of emotion that is so raw and so human that at times the experience becomes too familiar, and too eerie.

We live in a time of great disquiet, and art is always a reflection of its society. Narratives about imperialism, class struggles, state violence, and unchecked capitalism have become increasingly common, especially in the indie scene. Signalis explores this at its most direct level, taking us to a point in time where a militant organization seeks to control identity itself. It is here that we see the smallest and most profound type of rebellion: two people in love, living on their own terms at the end of the universe. The Eusan Nation government seeks to squash out art and self-expression to the point of absurdity—they have to reinstate small joys back into the lives of the Replikas after discovering that removing all sense of identity drives the units insane and makes them inoperable. The bit of agency allowed to each Replika unit—and the slightly more human Gestalts—is only permitted because it fulfills the needs of the state. It is here that Signalis grants us a glimpse at a sort of monstrous fascism whose tentacles reach beyond the stars.

This Deep Vibration Of The Cosmos

Elster grants the player a view of what the Replika units were like before their corruption transformed them into monsters. Place by place, room by room, we find snippets of diaries that build extinguished lives.

"I don't want to die, I don't want to live anymore either. Everything is just so exhausting. I just want to lie down and disappear."

The philosophy present in Signalis challenges the fragile concepts that hold our lives together. So many of us can understand this plight of temporary non-existence—how does one remove oneself without succumbing to death? As Elster searches deeper through the planet for her missing lover and comes across the surviving Replikas, she finds her answer in the influence of control. This is the classic mode of all fascism: destroy art, erase identity, and grind existence down to uniformity. It seems even under the extremity of such a regime, two people in love will do whatever they can to hold on to one another.

After eight hours forty-one minutes and fifty-five seconds of game time, I rolled credits on a game that had grafted a piece of itself to my soul. These are the sorts of experiences that can only be found in video games—narratives that cannot be contained by page or screen or sound alone. When the pieces are peeled back from the rotted slackened skin of misery and despair, hope remains in the ashes. Perhaps this is why I ultimately love survival horror so much, and horror in general; there is a hope here that feels earned only when you are wreathed by complete misery. If you can find your way into Signalis, do so. It's unlike anything else you've ever played.