Sifu: Revenge and Martial Morality

Revenge and redemption

"Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves."

Confucius

Sifu's tale of revenge is a tribute to the martial arts films of old, with all the genre's stylings and cinematic flair. From this foundation flows an undercurrent of heart that focuses on martial morality and Confucian values. Its arcade sensibilities elevate its martial arts basis of repetition equals mastery. Combined, it is ultimately a story about being better and uses its mechanics to push the player to such ends.

Crafting a revenge story can be a tricky task. It tends to carry a feeling of moral obligation for the writer not to condone the act of seeking revenge. Typically, stories in this vein see everyone suffer; the avenger coming away having lost more in the process, becoming a monster themselves, and realizing it solved nothing as they sit in the ashes of their life or take their final breath. Even when the initial crime is so heinous that the audience roots for vengeance in the name of justice and all that is good, the hero will perish in the end. We love a good revenge story - it's ideal for the action genre - but rarely does it break the mold. One can only learn the lesson in hindsight. By the time the deed is done, the punishment is unavoidable.

Sifu's tale of revenge and martial morality manages to create a unique conceit that tackles the philosophy and structure and uses the medium to elevate it. It's this galvanizing of story and gameplay that makes it an experience only possible in this medium.

Revenge

Sifu 師傅

"Teacher", "Master", "Father"

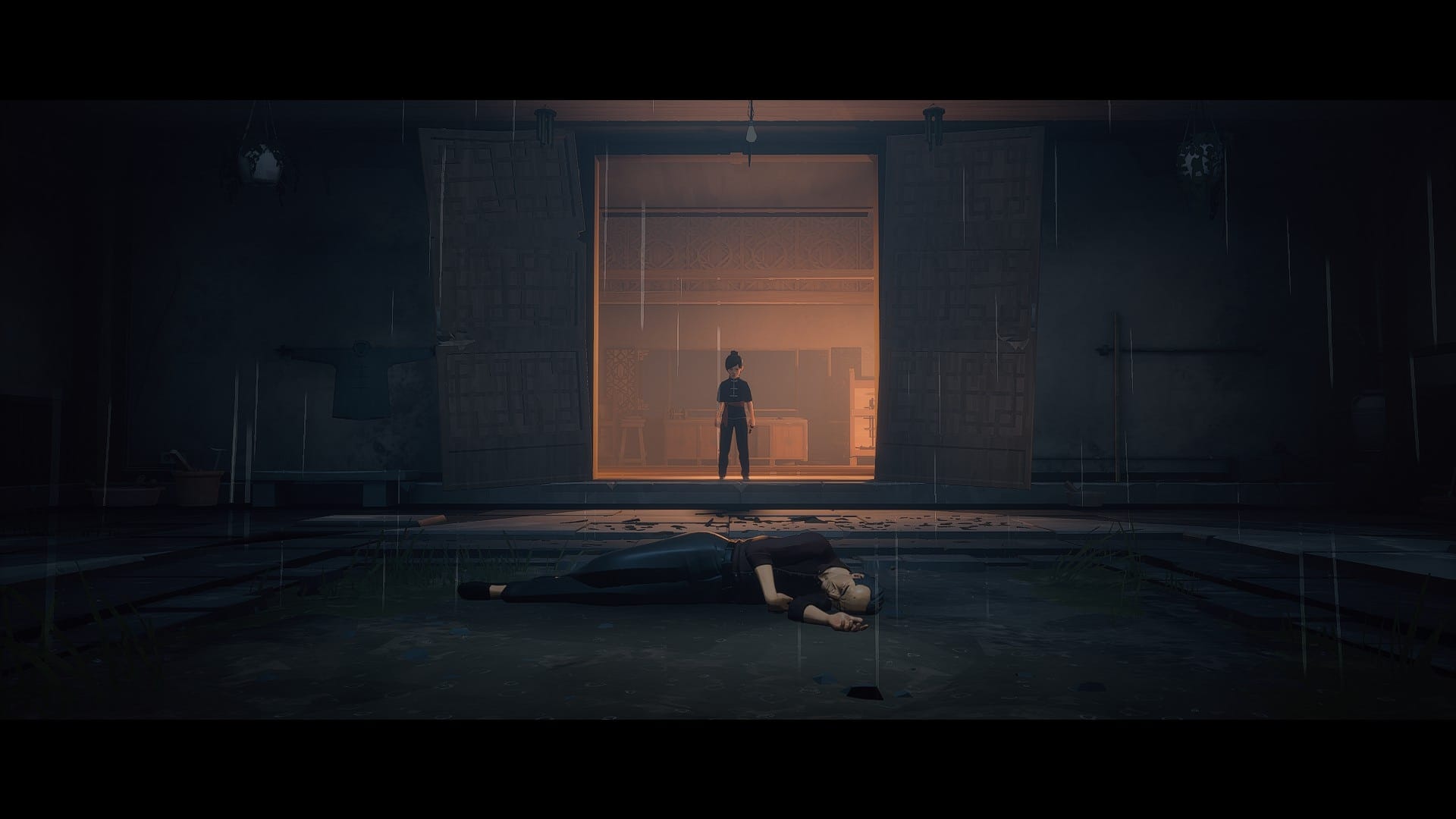

The story begins in darkness and rain. A man named Yang, backed by his four companions, leads an assault on his ex-master's dojo. Their goal is to secure a set of mystical talismans from this school and others that are protected rather than used and potentially abused. They kill the disciples and the master, whose child can only watch from a cupboard. The child, a boy or girl of your choice (referred to as Yin from here on) is found and Yang orders their death too. There can be no witnesses - no avenger to this new order.

Unknown to them, Yin held one talisman with the power to heal fatal wounds at a cost. Yin awakes to a shattered home and the body of their father.

Yang's motives are unknown to the player and child at this point. Yin is in the dark, unable to see the complexity of the adult world, and chooses the singular and childish path of revenge.

When Yang trained under his Sifu, he struggled with the concept of safeguarding these talismans when they could be used for so much good. When his wife and child were dying, Yang had enough of this rule and tried to use the talisman but was stopped by his master. To Yang, his master let his family die when he could have saved them. It was betrayal and senseless death.

Many Kung-fu and Wuxia narratives have objects of great power in their story. The reason for this trope and why these objects are protected rather than destroyed is because of what they represent in the context of martial arts wisdom. The power is always at hand - always an option - but is chosen not to be used. It is this restraint that is at the core of martial morality and the story of Sifu as well.

The ethics behind protecting the talismans are twofold. While good can be done with them, it is more likely that those with power will use it to further their own interests. The other is that it marks the death of the spirit. Over-reliance on such a thing can lead to stagnation. If we can not help others, preserve our earth, and strengthen ourselves through discipline without a magical tool, then do we deserve such a thing?

The five assassins and the enterprises they established in the following years demonstrate this flaw.

Fajar, the Botanist, holds the Wood Talisman. While he has the power to grow plants and food, he instead focuses on a purple flower that is made into an addictive drug called Purple Mist. Fajar and his gang preside over a rundown residential and industrial district that they have driven into poverty, creating a crime-stricken dump. The concrete jungle that is slowly being grown over by nature hides the beating heart of the operation: a greenhouse where Fajar hermits himself.

Sean, the Fighter, holds the Fire Talisman. He runs a club and a secret dojo within where he rules over disciples with fear and a strong hand, thinking strength is paramount. He is unable to see anyone as equal, blinded by the artificial growth of his strength and so he can not pass on any wisdom to the next generation. Their fighting is without morality.

Kuroki, the Artist, holds the Water Talisman. She maintains an opulent art gallery and museum; her disciples are now her security team. Self-exiled, ridden by guilt and fear of her own capacity for violence, she dives into art, struggling to come to terms with identity and the death of her sister at her own hands.

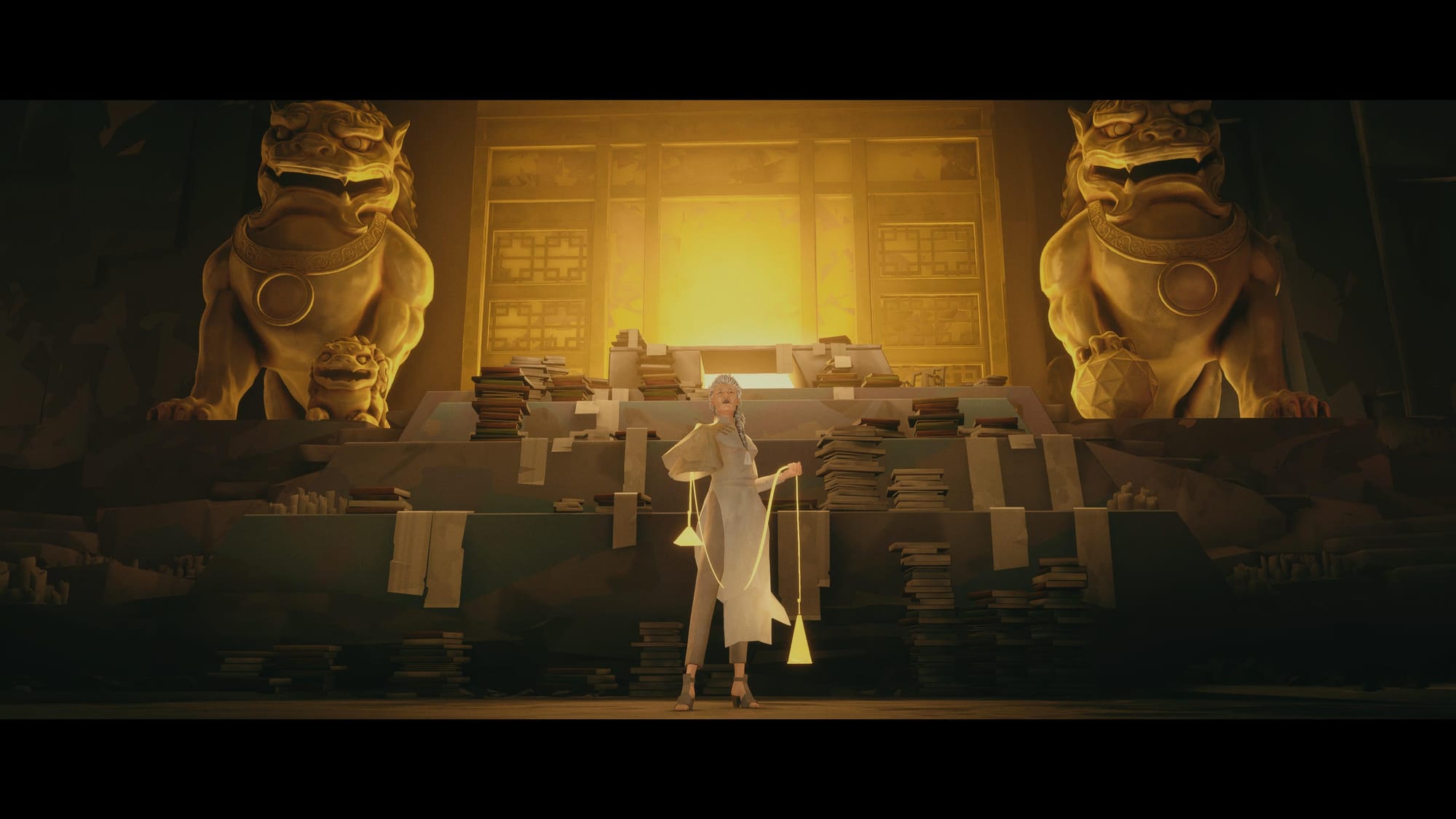

Jinfeng, the CEO, holds the Metal Talisman. A successful businesswoman, a pillar to the community, a donator to charity, and a leader of assassins. Her skyscraper stands as a monument to her own hypocrisy, hiding a golden tribunal in the caverns below where she doles out her own brand of justice. Using the talisman for riches and her disciples as muscle, her good deeds are as self-serving as the pain she deals with the other hand. She has forgotten her duty to others.

Yang, the Leader, holds the Earth Talisman. He runs a facility in the mountains - a sanctuary - where people come to be healed, both physically and mentally. People are said to have gone missing from there, perhaps indoctrinated into this new and growing order. He heals for self-interest, something that will make up for the father figure he killed and the family he could not save.

Source: Author.

Yin is twenty years old at the start of the narrative, having trained for years to take on their hit list. A board of the five assassin's pictures, locations, and information is set up in their home like some obsessed detective's mural. While Yin's talisman can heal their mortal wounds, it comes at the cost of years of their life, a devastating display of how much of your life you choose to spend on revenge.

As a gameplay conceit, this works as a "lives" system. Death ages you and deaths close together multiply the years wasted. As Yin ages, he/she is stronger but can take fewer hits. The fighting mechanics are nuanced and take practice. Every enemy in the game is a trained martial artist making no one simple fodder.

Sifu's tough difficulty, intricate fighting system, and aging mechanic lend themselves perfectly to the martial arts lesson of discipline, focus, and repetition equals mastery. It's an art that must be learned. Like games of the arcade era, it becomes about doing better rather than simply moving forward.

With Sifu’s arcade stylings giving it a lives system, most first-time players will reach the ending having spent most of them, leaving Yin as an old man or woman at the time of Yang's defeat. Yin has quite literally wasted the years of their life in pursuit of revenge. The story ends not in celebration or catharsis but on the protagonist’s aged face, feeling empty and unfulfilled.

The story does not fade to credits, it instead leaves its audience with a message:

"He who has Kung-Fu and Wude, makes the other know he can break him. His hands go out like lightning, and the other doesn't want to fight anymore."

Then the story restarts. The lack of epilogue, credits, or even a return to the menu makes the ending feel rather abrupt. It leaves the player with a dissatisfied feeling after fighting through hell, just as Yin does. It feels less like the ending and more like a splash screen for a game over state. But more accurately it's a halfway point.

What if you were given another chance?

Wude

Wude 武德

武 Wu - 德 De

武 Martial - 德 Morality

Wude is made up of two characters: Wu meaning martial and De meaning morality. In traditional Chinese schools, the study of martial arts was not simply a means of self-defense, but an ethics system. Wude deals with the virtue of the deed and the virtue of the mind, to create a harmony of emotion and wisdom. For mastery of martial arts without mastery of the self is just violence.

The message at the previous ending hints at an ability and method to do things differently. This method in both gameplay and story is sparing the lives of the five assassins who wronged Yin. This is done through gameplay by a mastery of the combat and knowing your foe. Through story it is done by instilling in them, one of the five Confucian values the game and its stages model themselves after. Yin reforms instead of killing. Instead of crossing out their photos, he places the character of the value next to them. He is "teaching them a lesson".

Sparing them is done by depleting the foe's structure rather than their health. It is tougher to forgive than hate, and the gameplay reflects this. Yin and the player, both show restraint and mastery within the fight, now able to play less aggressively. To block, dodge, deflect, and counter – tiring the opponent out – is to hold back.

One of the more difficult habits to break is not hitting the execution button prompt at the end of a fight; something that is practically a reflex after your last playthrough, working on both a visual and audio cue. It is a small detail but it is gameplay reinforcing the idea of holding back and having mastery of your baser instincts. You must inhibit your impulses to achieve Wude.

What was a tale of revenge is now one of absolution.

Yin sparing Fajar, teaches him the Confucian Value of Rén (仁) - Humaneness.

Of humanity, goodness, benevolence, and love. Fajar was the one who killed Yin as a child and Yin is demonstrating forgiveness. The scene of tea and a potted plant after tells us Fajar has turned to healing.

Sparing Sean, teaches him the Confucian Value of Li (礼; 禮) - Proper Rite.

Of ritual, conduct, and brotherliness. Yin teaches Sean humility. He proves he is stronger and lets Sean stand at the end of their fight, as though it was a simple sparring match. It demonstrates respect; the conduct and rite of passage where there is no shortcut. The scene after shows that Sean has thrown his sign "I am the solve sovereign" into the fire, marking a change in his mindset.

Sparing Kuroki, teaches her the Confucian Value of Zhì (智) - Wisdom. Of seeing right versus wrong, understanding oneself and others. Yin demonstrates restraint is possible instead of violence. Letting go instead of revenge. That if he can forgive her then she can forgive herself. The scene after, showing the doll and kunai together shows a mending of her internal struggle.

Sparing Jinfeng, teaches her the Confucian Value of Yì (义; 義) - Justice. Of honor and morality. By sparing her life, Yin demonstrates that he does not judge her as he has no right to do so. None of us do. Personal vendettas do not align with justice. The scene after showing the old bell and scrolls shows she has remembered her duty as a guardian.

Sparing Yang, teaches him the Confucian Value of Xìn (信) - Integrity. Of faithfulness and sincerity. Yang has spent years compounding his mistakes and regrets from a past that he is powerless to change. Now, a remnant from his past has walked through his door. A sibling from his martial arts family - an image of himself. Yin not dealing the final blow demonstrates forgiveness and makes Yang choose between bettering himself or adding to his regrets.

Source: Author.

Yin demonstrates that they can kill the assassins, but elects not to. Yin still takes the fight to what before was the killing blow - when his enemy has no chance of survival - but then spares them. Yin still has a machete at Fajar’s throat but releases him. Yin purposely strikes the ground next to Sean’s head with his staff. Yin turns the kunai to the handle when dealing the last blow to Kuroki. Yin wraps the rope around Jinfeng’s neck but then releases it. Finally, Yin holds back on a fatal blow to the heart of Yang at the cost of their own life.

But this time we end with a smile. It is up to Yang and his cohorts to do what they will with these lessons. But no matter what Yin is at peace, free from revenge and violence, having achieved Wude.

武德