SANS LINGUA FRANCA: Playing Games I Couldn't Understand

The context of languages known and unknown

As a kid, playing games in English or in Japanese felt the same to me. I was not a native speaker of either language, but I loved the games nonetheless. It wasn’t that I didn’t care about their stories — quite the opposite, I’d say — but that I had a limited set of tools through which to understand them. I relied mostly on visuals and style, framing, and the music accompanying them to infer the tone and importance of the scenes. I used to get extremely excited by flowery visuals and dynamic movement (even on sprites!) just so I could imagine the details of what was being fought over.

The Space Between

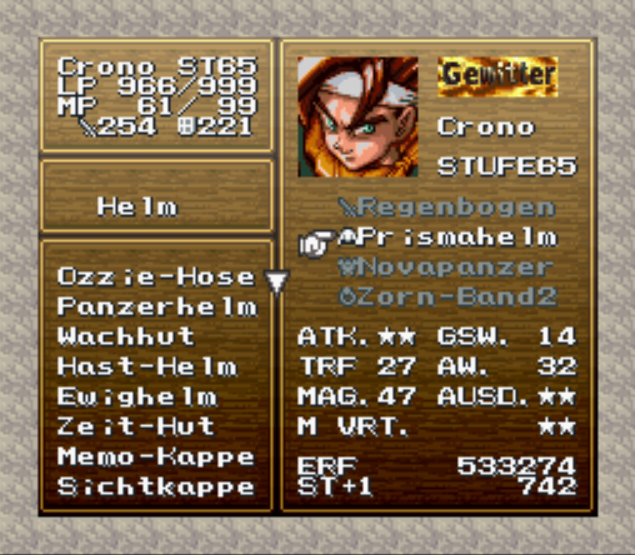

Although it would be easier to just play simpler games that didn't have such long text to parse, I liked the feeling of pressing the buttons repeatedly to pass those numerous text boxes when playing JRPGs. But since numbers are universal, their battle systems – even with hidden intricacies – were more intuitive (or so I thought, at least). For a long time, the core loop of a JRPG for me was to speak with everyone in any given city or village until a cutscene would trigger, showing the entrance to a dungeon or the next spot on the map.

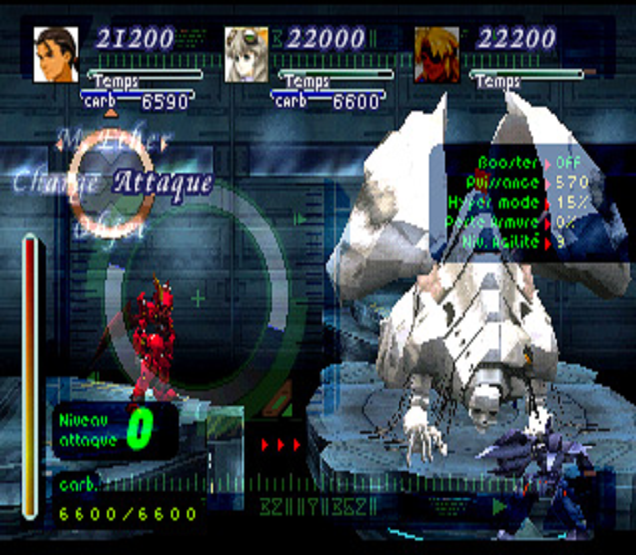

In games like Xenogears or Breath of Fire IV where we could rotate the camera around, finding all NPCs on a map became harder to do. They sometimes hide around corners or behind buildings. I had to learn how to read things as tips even though they were not necessarily designed to be seen as tips. I would note small dust puffs or how long someone would take to run around a building. I would even see the way textures were warping around models in the old PlayStation hardware: everything was a sign of something hidden, lurking, holding the key to another point of progression. The best thing we had at the time, considering there was no easy access to the internet, were magazines. But those were too limited, in both content and scope, to quench a young boy’s ludic thirst.

Creating meta-gameplay was a powerful argument for the magical power of play. Kids are creative, and even though we knew the rules of the game and knew we didn't understand the language, we were able to find our own fun without bitterness at the gap between us and the game. We had to create our own rules, and therefore we were culturally wired to learn how to play games very differently than the rest of the anglophone world.

When I discovered emulation and, not long after that, fan translations, I was astonished. There were games that people translated into my language. Hindsight – and the internet – let me know that there were quite a few translated games available, but at the time they were more of a myth. At least this was true for the games I wanted to play and for consoles as a whole.

One of the first games I tried playing in my language was one that had already become a favorite after I had played it in English: Super Mario RPG. It had a very clear and distinct visual flavor, using a button-coded menu (similar to Persona 5, for those that never played the old Mario) that made things easier even during battles. There was simple, linear exploration and a lot of visual gags that I could more easily understand. After all, Mario didn’t speak, so any explanations he could give to the other characters were by theatrics anyway. The amazing Yoko Shimomura soundtrack took me by the hand and explained to me that I was supposed to feel joy or tension just by its notes. It’s hard to explain how the cloud-shaped Mallow’s crying animation, and the rain that accompanied it, became an emotional plot point after being a quirky joke for so long. When I reached the clouds, I understood everything that I needed to understand.

Most of my initial suspicions about the plot were validated and confirmed after I played the Portuguese version. It was also great to see other details too: the way that the shark pirate speaks in platitudes was something that went over my head when I was playing in English, but the translation team put a lot of effort to make it seem as pompous in Portuguese as it was in English, and that same joy and care could be found throughout the game. I already knew who actor Jet Li was, but seeing the translators replacing Jet Li with “Massaranduba” – a famous (at the time) Brazilian comedy character – in order to explain to the audience that they were talking about someone who was good in a fight made we aware of the concept of localization.

However, the heart of this story is the following: there’s a side quest in Super Mario RPG where you find a secret casino. You hear about it from one of the bosses you beat, but there’s also more information scattered around the world. Some characters – mainly monsters – talk about it sometimes. The thing is that it's actually pretty cryptic and hard to get to: you need to find a secret passage that contains a pipe, defeat a strong enemy, and finally jump a couple of times in front of said pipe in order to trigger a platform to appear. There’s a certain toad in a certain inn that gives you the needed hints to find it, so when I played in Portuguese and saw this toad I was really happy when he murmured something about the secret casino: of course I wasn’t able to find it in English. It was basically new content for me.

When I played the game in Portuguese, the toad’s text was blank. It was a bunch of empty text boxes you needed to press through. At first, I thought the game was bugged, (“parece que deu tilt”, as we would say in my language), until the last text box appeared, explaining that it was a decision by the translation team to leave them blank, otherwise it would be too easy to find the casino.

The sociopolitical gravitas of that was lost to me at the time, of course. I just wanted to find the casino. I didn’t think about the implications of the idea that it should be harder for anyone who doesn’t speak English to find the same information as someone who does. However, I’m sure that was lost on the translation team as well. They probably just wanted to make it more fun and surprising in the only way they knew how, being that they had an understanding of the same difficulties - and fun times - I had experienced as a non-English speaking kid.

Discovering Through Play

Stumbling around in the dark was part of our core gaming experience, and yet we still loved it. It would be unfair to give us directions to the casino because we aren’t supposed to know what they are. That’s not how we grew up. The games we played demanded more from us, even though they were the same game others were playing in English. It’s a fascinating bubble to grow in when you don't speak the languages of the games you're playing, and it offers great academic insight. It’s also probably something that won’t happen again, fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on how much you value nostalgia), as games get translated more broadly.

It’s great that companies are allocating more and more resources to localize games in as many countries and languages as possible, instead of stopping at English and demanding we accept that as the norm. Although playing fan translations nowadays is easier than ever, and a lot of games that were stuck in Japanese during the 90s and 00s are now accessible to a bigger audience, which is also a way to increase cultural reach and allow for broader historical analysis.

Nevertheless, playing games without understanding them can also be an amazing gateway to recognizing spontaneous design quirks that people can notice when they're trying to parse more information on less. A lot of people learned English and Japanese because they played games in those languages as kids, so why stop at just those?

The act of playing is itself bursting with creativity, no matter the kind of tutorial or game design tool created just for it, play is freedom. When playing something that you don’t understand even with its own lexicon, we allow untold stories to appear, new chronicles of the adventure to explode into existence, and navigate puzzles beyond the ones purposefully created by the designers.

Like any kind of art piece bound by language, playing games outside of our own creates deeply distinctive and individual experiences, and it will always show a different kind of friction that can even enhance the piece itself.

Look for games that use words that you don’t understand. You may be surprised – like I was – by the feeling of discovering your same favorites all over again.