Resident Evil at 20: Reimagining ‘Ground Zero’

Examining the origins of Resident Evil's film franchise and its contrast with Capcom's games

2002 was an exciting year for the Resident Evil franchise. Barely a decade old, by the early 2000s, the series had sold about 16 million units. What began as a reinterpretation of a movie tie-in game, Sweet Home for the Nintendo Famicom, became a bona fide franchise and genre innovator. It branched out into comics, action figures, and novelizations by S.D. Perry (an author who you love or hate if you’re a fan of the series).

To put it mildly, Resident Evil was on top of the world. The only thing left to conquer was Hollywood and the big screen.

Aiming for Hollywood

In The Making of Resident Evil, former Head of Production for Capcom, Yoshiki Okamoto, recounts, "We have been told that the game contains movie elements, and we hoped that the game would become a movie as soon as possible."

The sentiment wasn’t without merit. While the original Resident Evil started as a remake of Nintendo's Sweet Home adaptation, the game eventually leaned more toward the horror films of George A. Romero or John Carpenter and away from the Japanese physiological horror narratives of its time.

Infogrames' Alone in the Dark cemented the project's cinematic zeal. It pushed the dev team to scrap their initial first-person gameplay perspective in favor of the now contentiously remembered fixed-camera angle perspective and tank control scheme.

"We have been told that the game contains movie elements, and we hoped that the game would become a movie as soon as possible."

Yoshiki Okamoto

(former Head of Production at Capcom)

When considering Resident Evil’s filmic roots, if Capcom was aiming for a purely Japanese audience, I don’t think Kiyoshi Kurosawa–director of Sweet Home, Cure, and Pulse—would be out of the question for a live-action Biohazard film, if only because the director and Capcom have a working history together. Kurosawa and late writer Juzo Itami co-produced Capcom’s Famicom RPG adaptation of Sweet Home. They went as far as encouraging Sweet Home developer Tokuro Fujiwara to focus on making the game unique over a derivative film-to-game experience.

By 2002, Kurosawa’s profile was, I’d argue, that of an “auteur.” He could move between genre films and major dramas with little consequence to his public-facing career. At the time of Resident Evil’s US film production, Kurosawa directed both Seance and Pulse. Pulse became one of many formative horror films out of Japan during the new millennium.

After the production of Resident Evil 2 for the PlayStation, the Hollywood machine attempted to turn Resident Evil into a blockbuster franchise. Constantin Film, a German production/distribution company, acquired the film rights to the game and cycled through several screenwriters, including Alan B. McElroy and George A. Romero, director of Night of the Living Dead. McElroy’s credits as a screenwriter span gaming and comics, notably in collaboration with Spawn creator Todd McFarlane. Like Uwe Boll, McElroy intended to make his mark in the industry with video game screenplays. He wrote one of the first unproduced film screenplays for Id Software’s Doom and the screenplay for the live-action adaptation of Namco’s Tekken series. His reputation as a horror screenwriter is middling, starting with Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers, Wrong Turn, and its straight-to-streaming remake. His involvement in Halloween and Spawn is likely why he got the Resident Evil gig.

Romero, who directed the Japanese TV Spot for Resident Evil 2 and who succeeded McElroy, seemed destined to make something to appease Constantin Film and Capcom. However, in an interview with Fangoria published in 2002, Romero lamented that the head of Constantin at the time (Resident Evil producer Bernd Eichinger) didn’t like his script. “The head of the company just did not understand it, doesn’t even know what a video game is. He wanted it to be something different. [...]He wanted something prestigious. I told him that’s not the spirit of the game.”

Fangoria and PlayStation Magazine describe McElroy and Romero’s scripts as “action-packed, gory, and like the game(s).” However, a combination of issues, including multiple rewrites and the release of Resident Evil 2, ultimately led to those scripts being rejected. The descriptions aren’t without merit, and as proven repeatedly, “It’s like the games!” will satiate and appeal to fans keeping track of movie productions.

Romero’s take on Resident Evil was aimed at an adult audience. The script's material earned it an NC-17 rating. Because of the investment put into pre-production at that point, Constantin felt the rating would affect the return investment typically gained with a lower rating, be it PG-13 or R.

For Capcom, McElroy, and Romero’s scripts shared a common issue the company was looking to avoid in the film adaptation of the franchise. Even with certain elements altered for the screen, the scripts were too much like Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2.

Enter Paul (W.S.) Anderson

Before the release of Resident Evil 2, New Line Cinema courted Anderson for their adaptation of Midway’s Mortal Kombat, a controversial arcade game and political catalyst of the ESRB rating system. Anderson’s independent debut, Shopping, landed him opportunities otherwise unavailable at the start of his career.

When news circulated about New Line Cinema’s gambit with Mortal Kombat, directors turned their noses up at it. And it wasn’t without reason. Video games were considered low art, if they were considered art at all. Film adaptations of video games were in a bad place in the early nineties.

Super Mario Brothers, Double Dragon, and Street Fighter—films with cult followings now—failed to perform at the box office on release, marking the genre as poisonous. The industry thought them no better than Plan 9 From Outer Space. This string of blockbuster failures was the foundation for the “Video Game Curse” (VGC)—an outlook that damned a video game adaptation before and after its release. Toward the 2000s, the phrase would lose all meaning. It became shorthand for any adaptation failing to meet certain expectations, regardless of how close it stuck to the source material. If you were an Angry Video Game Nerd-type, forum discussions about the VGC conjured some fairly low-hanging fruit about the sub-genre of films. Goalposts got moved or were outright ignored by the vitriolic and misogynist framing that typically permeated the conversation. There was a particular culture within then-dominant gaming forums that went after video game adaptations like Lara Croft: Tomb Raider and Resident Evil in ways that made it easier to deride gamers within pop culture. The depiction of Angelina Jolie's Lara Croft and Milla Jovovich's Alice came under a kind of gendered criticism that devolved into calling them "Mary Sue" ("a female character I don't like") or sexy lamps. In the same breath, gamers reduced the game version of Lara Croft or Jill Valentine to physical attributes (as a positive) without a hint of irony. It's the kind of sentiment that was one of many seeds for the foundation of an entitled and violent movement years later.

For a time, gamers believed that game studios could save film adaptations of their favorite games, but that wasn't entirely true. Hironobu Sakaguchi’s Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, produced by Square Pictures (Squaresoft’s film studio), was a passion project and a tech innovator in the film industry. Yet, despite Sakaguchi's involvement, it failed to meet the bar of a “true” Final Fantasy story for fans. The mixed reception for Disney’s adaptation of Jordan Mechner’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time spurred Ubisoft Film & Television to produce the Assassin’s Creed film. No one talks about that Assassin’s Creed film. Later films such as Resident Evil: Welcome to Raccoon City and HBO's Mortal Kombat reboot espoused some element of “we’re going to stay true to the ‘spirit’ of the games!” in their press tours. In the end, they weren’t treated any better than their predecessors. Again, they failed to meet specific criteria for the gaming audience. Sonic the Hedgehog (and its sequel) and The Super Mario Bros. Movie had no quantifiable quality markers, yet most audiences more than love these adaptations. The quality of a game’s film adaptation depends not on the publisher, developers, or fans' desires. It’s a crapshoot.

To his credit, Anderson never put much stock in the idea of game adaptations as a cursed medium. "Lots of books get adapted and the adaptations don't work, but no one is saying book adaptations are cursed," Anderson argued in a 2020 interview with Entertainment Weekly on the legacy of his Mortal Kombat film.

There’s always the question of how Anderson’s post-Kombat career survived. Aside from being Uwe Boll’s antithesis, I think this mindset about his chosen pet genre has carried him this far. Good or bad, he doesn’t allow the general perception of video game adaptations within fan or film culture to worry his approach to it. That’s a big part of why Anderson is experiencing an unironic “renaissance” almost thirty years into his career as a writer and director.

Mortal Kombat debuted in theaters to financial success. The film's reputation experienced a cycle of push-back and ironic praise before consensus cemented Anderson's film as God-tier schlock among gaming fans. It’s The Mummy of video game adaptations.

Anderson would direct Event Horizon and followed it up with another troubled production in the sci-fi/action film Soldier (starring Kurt Russell). Neither film performed well at the box office, and the burned-out director would retreat to his beachfront property in Venice. There, he began a long play session of Resident Evil and Resident Evil 2.

Anderson, taken with the atmosphere and story of the games, communicated to his production partner, Jeremy Bolt, that he wanted to make a Resident Evil film. Romero, Capcom, and Constantin were still in negotiations about Romero's script, but in Anderson's own words, “[...]I heard rumblings that it wasn’t going terribly well with Romero, and that it might not happen.” (Salisbury, Fangoria, 2002) Undeterred by the current goings-on with Constantin and Romero, Anderson wrote his send-up to Resident Evil, titled Undead.

His idea, “Very much an idea that would probably get [him] sued,” did nothing out of the ordinary compared to McElroy and Romero’s scripts. The setting followed the beats of the first Resident Evil down a ‘T.’ The forest, the mansion, the underground laboratory, and the stand-in for the Umbrella Corporation. “[...]from the outset I was writing Undead with an eye to it becoming Resident Evil.” But, where McElroy and Romero's stories were mere retellings of the games, Anderson was interested in the 'origin' of the T-Virus outbreak, the catalyst for the mainline games. "I felt the Ground Zero idea was the correct approach for both people who had never heard of the game and were unfamiliar with it and for the avid players who will adore all the references included in the action-packed scenario just for them." Also working to Anderson’s advantage was Constantin's desire to work with him on other projects since his debut film. Eichinger was happy to set aside the unsuccessful deal with Romero to get a glimpse at Anderson’s script.

“Bernd was ecstatic, and we joined forces,” recalled Jeremy Bolt to Fangoria. Anderson and Bolt’s deal with Constantin Film involved selling half of Impact Films (their production company) to Constantin as part of an overhead financing deal to make Resident Evil.

As pre-production for the film began in 2000, Anderson was officially announced as the director. The following year, actors Milla Jovovich, Michelle Rodriguez, and James Purefoy were among the first cast announced for the film. Actor David Boreanaz was reportedly "in talks" to play the film's male lead or a smaller role. He passed on the film to star in his own series (Angel), and the lead role went to Eric Mabius.

REimagining Nintendo

Coinciding with the production of Anderson's origin story for the original Resident Evil was Capcom Production Studio 4's re-imagining of Resident Evil for the Nintendo GameCube.

Within the hollow theater of the 2000s Console Wars, developers like Sega and Nintendo, once dominant in gaming hardware, salacious advertisement, and titles that defined the '80s and '90s, were on the back foot. Their competitor, Sony Entertainment, announced their second generation console—the PlayStation 2. Software giant Microsoft expanded its reach within the gaming industry beyond the home computer with the launch of its debut console, the Xbox.

For all the reverence many hold for the GameCube in the here and now, for the uninitiated, Nintendo's then-latest console gambit was not considered “a contender” in the Console Wars. After the Nintendo 64’s considerable market loss to Sony’s PlayStation (PS1), Nintendo’s limited ability to cater to the needs of third-party developers left the corporation struggling to convince studios eager to work with Sony and Microsoft that their latest console was worth investing in. Like the N64, GameCube’s software intentionally limited how much data could be stored on a mini-disc, requiring publishers to manufacture multiple discs versus the single DVD-R for the PS2 and Xbox. Nintendo’s reluctance to enter the fledgling online gaming market created extra friction for consumers and developers. It was on the consumer to purchase separate, officially licensed software accessories, and developers had to create dedicated servers that weren’t long for the world. Nintendo also didn't invest in the growing multimedia market. So, comparatively, the GameCube looked more and more like a relic of the gaming past compared to how eagerly Sony and Microsoft embraced the idea of their consoles acting as supplements for highly expensive DVD players. It reached a point where the accepted image of video games as a medium for children eventually worked against Nintendo. Sony and Microsoft leaned hard on the perceived ideas of maturity and edginess appealing to twentysomething men.

Nintendo’s exclusivity deal with Capcom, announced in 2001, seemed like an attempt to challenge the idea that they wouldn’t (or couldn’t) cater to an aging gaming audience. It was also a show of faith by Capcom, one of the biggest third-party developers in the industry. Metroid Prime, Eternal Darkness, and re-release of the original PlayStation Resident Evil games were one way Nintendo hoped to shake audiences of the growing sentiment that the corporation couldn’t make adult games. Capcom and Nintendo’s famed “Capcom 5” titles also attempted to bolster an image of maturity for audiences, marketed as exclusives for the GameCube. PN03, Dead Phoenix, Resident Evil 4, Grasshopper’s Killer 7, and Clover Studio’s Viewtiful Joe. While not among the "Capcom 5" titles, Resident Evil Remake was produced under console exclusivity and used as a major selling point for the GameCube.

Nintendo’s exclusivity deal with Capcom, announced in 2001, seemed like an attempt to challenge the idea that they wouldn’t (or couldn’t) cater to an aging gaming audience.

Capcom’s partnership with Nintendo ensured that any upcoming Resident Evil titles leading up to RE4 would be anchored to the GameCube. Even as those tenants quickly dissolved in the name of expanding profits, Remake and its prequel, Zero, would not see a multi-platform release until 2015 with the “HD Remaster.”

By 2001, the original Resident Evil was a product of its time. The aesthetics of the rotting face on the cover of its Greatest Hits case gave way to dilapidated pixels and a localization that remains a chuckle-worthy artifact reflecting the lack of attention given to translation and voice acting in the medium. The proceeding soundtrack scandal, unearthed by the Resident Evil Director's Cut: DualShock Edition, in which Mamoru Samuragochi was neither deaf nor the original composer for Resident Evil, further muddied the legacy of the PlayStation original.

At its core, Resident Evil, like Alone in the Dark, is B-movie schlock with an interactive element. But doesn’t mean it couldn’t aspire to a presentation stronger than the sum of its genre trappings. Taking advantage of GameCube’s software, Remake director Shinji Mikami worked to create a version of the game that honored Resident Evil's legacy. “At the time the game was being developed, GameCube was the most suitable hardware in terms of allowing us to realise our vision with the title,” explained Resident Evil producer Hiroyuki Kobayashi in an interview with Darran Jones for 100 Nintendo Games to Play before you Die.

While Dreamcast-famed Resident Evil: Code Veronica was a fully 3D rendered game, Remake used motion video backgrounds to blend still images and videos within 3D environments. According to Kobayashi, a team of a hundred people worked for eighteen months to complete the game.

Complimentary angles

Mikami's Remake and Anderson’s Resident Evil are beginnings for different audiences. As Capcom intended, the stories approach the T-virus outbreak from radically different narrative angles. You’d be hard-pressed to engage with the ground-up reconstruction of Resident Evil in Remake and not consider it a full-blown re-imagining in the fashion of its successors almost seventeen years later. But Remake doesn’t recreate the story so much as it restores the structure imagined by the original dev team.

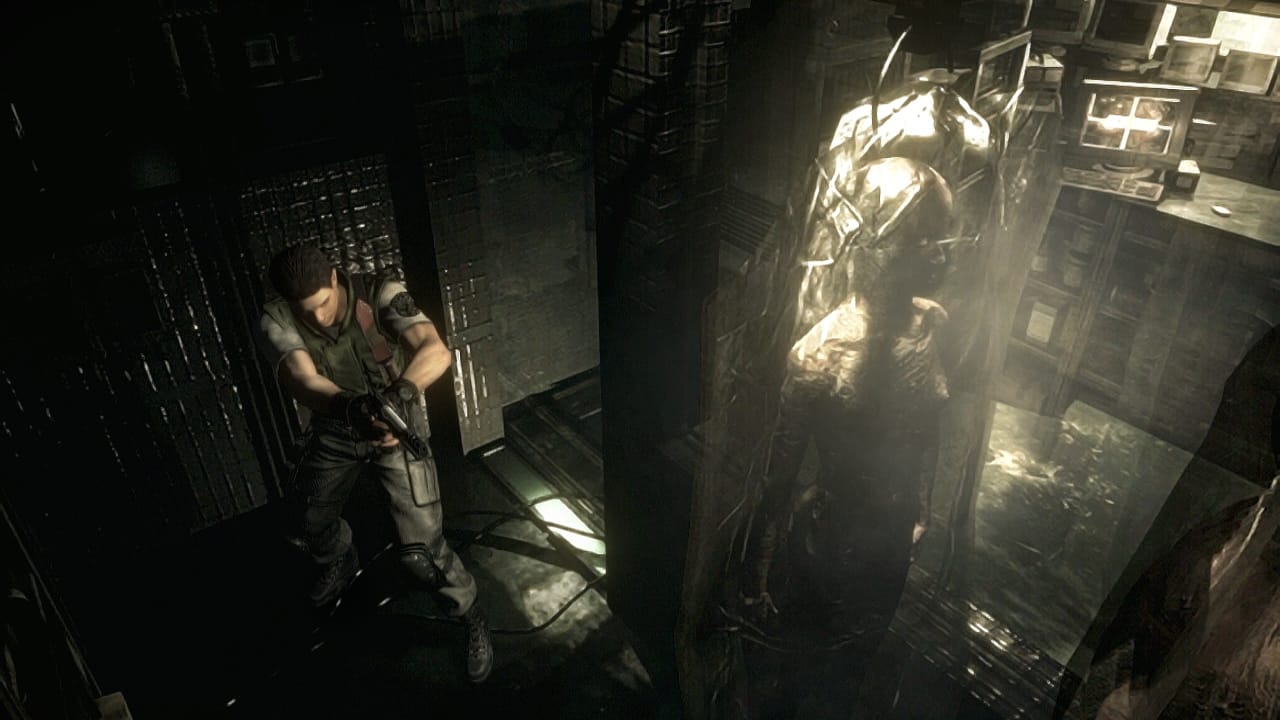

The schlock opening and character intros of the PS1 feel, compared to the gloom and grain of the GameCube cinematics, like the first draft of a story published hot off the press. The less sophisticated nature of its hardware and audience are suitable in that case. The more kitschy elements of the franchise, such as the giant plants, monster frogs, snakes, and hairy spiders, aren’t any less silly or any less a marker of the PlayStation’s hardware limitations. However, the uncanniness of their occupation within a near-photorealistic environment heightens the surrealism created by walking corpses whose decay takes on an unsettling dimension.

You’d be hard-pressed to engage with the ground-up reconstruction of Resident Evil in Remake and not consider it a full-blown re-imagining in the fashion of its successors almost seventeen years later.

Within Anderson's film, lab techs and pencil pushers whose lives you, as the player, would only glimpse through diary entries and research papers scattered throughout the game are—for a moment—given dimension in Resident Evil’s opening gambit.

The Umbrella Corporation is a quasi-monopoly in the vein of Amazon, with a presence in every sector and industry. But most people working for them aren’t the comical mustache-twirling villains of the games (yet). They’re working stiffs or researchers who either aren’t aware of their employers' ulterior motives or adopt just enough denial to justify their employment. Their reappearance as the undead is markedly more impactful in contrast to the S.T.A.R.S. team stumbling into the aftermath of the mansion’s inhabitants, already decaying and long gone from the exploitation of Umbrella. It makes Alice (a woman with no name until Resident Evil: Apocalypse) an interesting contrast to Resident Evil’s atypical paragon. Alice works for the Umbrella Corporation as a security officer within the Hive, the secret lab below the mansion in the woods. Anderson’s preoccupation with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland frames much of the amnesiac character’s discovery of her occupation. The laser room sequence and the antagonistic presence of the Red Queen A.I. are some of the few film elements that appeared in later Resident Evil games. There’s enough room within the narrative to suggest Alice’s anti-capitalist and environmentalist actions against Umbrella are a recent adoption. She was potentially complicit or ignorant of their exploitation until Lisa Addison (Heike Makatsch) persuaded her otherwise. Her dynamic with the likes of Umbrella commander “One” (Colin Salmon) and his empathy towards her hesitation about relearning what she did inside the Hive, clarifies that most working for Umbrella work for them with some understanding that they’re not a “good corporation.” Alice and Spence's amnesia allows the security operatives to “start over.” As technical hostages of the Umbrella tactical squad, the two characters are completely focused on helping the people around them when escaping to save their skin fails. Partners in apparent crime, with an explicitly sexual relationship, their paths fork when Alice works against the company, not in the name of profit, but for purely egalitarian motives.

Spence, in contrast, appears convinced that the profit he could gain from selling the T-Virus to the highest bidder can still win his ex-partner over. The “good” that he does throughout the film ultimately doesn’t matter when personal gains are reconsidered. Alice, whatever her original intentions before meeting Lisa Addison, commits to the person she’s become because of her journey.

Remake’s protagonists, by comparison, are upstanding American citizens of their hometown, Raccoon City. Part of an elite squadron of military-trained police officers, the S.T.A.R.S. squad investigates serial murders in the Arklay Forest. If the GameCube rendition does anything for Chris Redfield, Jill Valentine, and Barry Burton, it brings them closer to humanity than the original.

Writing for games is still choppy at this point in video game history. Direction and localization are stronger, but the usual awkwardness with dub syncing and Japanese performances in motion capture (Jill and Rebecca’s demure deference to their masculine partners) dates the game considerably. But the more subdued, ponderous performances match the foreboding tone of the game. The naked heroism in every character save Albert Wesker is hard to miss. There’s no real question about their alignment and no ambiguity in their role within the zombie conflict that would later define the series (Barry has to be blackmailed in dubiousness, for example). Jill, as the preferred player character (in my case), and her particular characterization in Remake have always struck me as teetering too close to “not as capable as the guys.” It’s a wild contrast to the Hard Boiled version of Jill Valentine from Resident Evil 3 Remake. Jill’s scenario saddles you with shady Barry Burton, who repeatedly rescues a startled Jill from first encounters with zombies or Indiana Jones-type traps in the Spencer mansion. In-game, Jill is only as capable as the person controlling her. Her efficiency against zombies grows with that of the player who learns to pick their battles, burn bodies, and honor the game’s scarcity tactics. Within the story, Jill and Rebecca Chambers may be rookies compared to Chris, Wesker, or Barry.

Chris’s characterization is almost quaint compared to the hyper-masculine action man he’d eventually become in Resident Evil 5 and onward. He’s just a "good guy" who trusts the people on his squad and suspects nothing is amiss with Wesker until he self-incriminates.

Unique to the GameCube releases of the franchise is a grimy aesthetic shared with the likes of Capcom’s stalker-horror, Haunting Ground, and the first Devil May Cry. Sepia and green tones of Remake and Resident Evil 4 create a visceral level of revulsion in their 3D and pre-rendered backgrounds. The original title screens adopt a metallic brown rust style, contrasting the bold red and white Arial font of past and present. The Macintosh-like inventory windows get replaced by a rustic, far more restrictive series of menus accompanied by an EKG needle on a paper monitor representing your health. Nothing feels or looks clean inside the mansion or its outlying environments, particularly in the spaces occupied by zombies who’ve rotted away. It almost justifies the Haunted Mansion vibe of the building. Researchers used to live in the mansion, but the rows of blurry portraits on the wall and the extravagance of the building’s overall design suggest someone of great wealth or history also lived there.

The clean-cut appearance of your player character (Jill or Chris) stands out against the dim lighting and dilapidated rooms and gardens, never muddying or adopting the wears of player events. Resident Evil 4 sort of takes this one step further with its characters.

Most characters look as haunted as the places they inhabit (Leon Kennedy and Luis Serra, in particular, look ghoulish compared to the brighter complexions of Ashley Graham and Ada Wong). This contrasts with the flat, JPEG-esque textures of Resident Evil’s mansion environment, full of bold browns, whites, and stone-like wall textures.

The film, formerly dubbed Resident Evil: Ground Zero (the latter part of its title was dropped following the 9/11 attacks in 2001), tries to ground the world of Raccoon City and the abandoned mansion into something concrete. Anderson and cinematographer David Johnson adopted a sterile visual aesthetic that became normative for science fiction films of the early 2000s following the release of The Matrix.

When Alice wakes in the mansion, the vastness of the clean-cut environment feels like a showroom. Beyond a lone red dress on the bed and the message, “Today, all your dreams come true,” nothing inside the mansion says it was lived in. The angel statue wrapped in plastic suggests the stages of mothballing. Down in the Hive, the Umbrella Corporation epitomizes deceptive cleanliness in its function as a pharmaceutical and military company. A false city behind blinds, mosaic artwork, and sterile environments (in keeping with a lab or hospital) creates an unsettling false front that its employees have learned to ignore. The Red Queen’s extreme containment measures, killing everyone inside, are swept behind sealed doors and locked rooms. Halon-induced death is so neat that none of the undead is allowed to sully the company front. That woman who lost her head to the elevator, the laser-mutilated corpses? In a clear nod to the memory limitations of the PlayStation, they disappear, leaving nary a trace that they ever existed. It’s not until they’re released from their respective prisons that the undead's apparent self-harm and mutilation degrade the environment. The questionably titled “Dining Hall B” reveals a series of tanks scattered within a bunker-sized room, with no trace of common areas. Seedier aspects of the Hive’s illegal experimentation spill out in the environment when the undead converge on the hall, and an explosion releases one of the Lickers. The Hive’s environments degrade further the deeper the characters enter the facility, eventually giving way to concrete sewers that hide none of the filth that the characters adopt as they’re mauled and stalked by the former employees.

Resident Evil never explores the ramifications of the Umbrella Corporation’s actions, and Remake follows the same pattern. The reveal that Wesker played a part in creating zombies and mutated animal life is treated less like an exploration into environmental destruction and more like a Saturday Morning Cartoon plot without the Captain Planet messaging. Its successors, Resident Evil 4 and Resident Evil 5, became bolder about surface-referencing global politics, specifically environmentalism, white supremacy, and the Military Industrial Complex. The Umbrella Corporation and its founder, Oswell E. Spencer, are products of white supremacist thinking. In all the ways that matter, Spencer’s desire to create a “superior race of human beings” (superior humans who are white, blonde, and blue-eyed) buttresses numerous human rights and environmental violations the company commits.

Extrapolated lore surrounding Albert and his 'sister' Alex Wesker (Resident Evil Revelations 2) establishes them as apparent clones of Oswell E. Spencer. The mansion in Remake—Spencer Mansion (or estate)—belonged to Oswell’s family. The T-Virus, its successors or progenitors, embody the modes of corporate exploitation. Its victims, zombies, and bio-weapons gone wrong, whether they’re people complicit in the virus’s creation or victims of Oswell’s plans, are just a byproduct of the business. The Trevor family, specifically the daughter, Lisa Trevor, gives a minor character more than just a journal entry for Jill or Chris to find. Players can interact with the mutated Lisa, whose chains rattle in the lower mansion levels before you even meet her. Oswell’s general lack of humanity is embedded in his delusions of becoming a god and dominating the world. Albert and Alex share that absence of humanity, which is fully displayed in Remake when Wesker admires the Tyrant's butchery as the pinnacle of creation.

"Resident Evil never explores the ramifications of the Umbrella Corporation’s actions, and Remake follows the same pattern."

Anderson’s Resident Evil isn’t much better with the subtext of capital exploitation and environmental destruction. Once he was no longer constrained by the idea of his film acting as an origin story for the games, the creation of his universe spiraled into Mad Max territory. The constant victories of the Umbrella Corporation, true to capitalism, destroyed the world, yet its executives continued to function as though profit was still the end goal. That said, his heavy handiness is very much a part of why the audience would initially have reasons to mistrust Alice despite her apparent altruism throughout the film. Eric Mabius’s Matt Addison, the Chris Redfield to Jovovich’s Alice (“Jill Valentine-in-spirit”), reflects the then-dominant culture’s idea of an environmentalist. Self-righteous, underhanded, and a terrorist. Even with no reason to trust Umbrella Corporation branded soldiers, the audience sentiment (of the day) was mistrusting Matt. His footing in the story shifts somewhat following the reunion and second death of his zombified sister, Lisa. There’s reason to believe Alice may have betrayed her and sabotaged the Addison sibling's attempts to expose Umbrella Corporation’s illegal experimentation to the media. It’s an interesting wrinkle that never comes to be. The ‘twist’ instead reveals that Alice’s partner, Spence, killed thousands of people to cover his tracks and protect his opportunity to profit from the T-Virus on the black market. Alice isn’t necessarily a “good person” because she wasn’t the saboteur, but she was trying to stop any means Umbrella had to spread bio-weapons. Spence, oppositely, mocks the idea of collective action and environmentalism.

For all the changes that Mikami and Capcom Production Studio 4 wrought with Remake, their aim wasn’t to create some dark and gritty re-imagining of the 1995 game. At this point, Resident Evil isn’t self-conscious about its schlockiness. The showdown between Jill, Chris, and the Tyrant remains unchanged and very gamey in its presentation. The B-movie horror gets blown up, and our heroes ride off into the sunrise, the evil defeated until the next entry. Amid the body horror and the newly defined grime, Remake remains optimistic and comfortable in its explicitly non-cinematic structure.

Anderson’s Resident Evil similarly devolves into a gamey climax, a sequence of events moving faster than most of the movie did in its middle or beginning. The miraculous survival of Kaplan (Martin Crewes) gives the surviving group, Alice, Matt, and Rain Ocampo, an out in a no-choice solution, after which Kaplan immediately dies. The subsequent train ride becomes a boss arena (similar but not identical to Resident Evil 2’s William Birkin boss arena), with Alice fighting a gigantic Licker and Matt fighting a hastily zombified Rain. But instead of the heroes riding off into the sunset, Anderson flips the traditional ending of Resident Evil with failure. Alice and Matt escape the Hive, but Matt mutates into this universe’s rendition of Nemesis. Alice is kidnapped and experimented on. The T-virus is set loose from the Hive in less than a few hours, decimating Raccoon City. Nothing was more devastating than when Alice drew to a halt outside the doors of Raccoon City Hospital to the ruination of the city. In a page taken out of the John Carpenter playbook, Alice stands alone in Raccoon City, the sounds of the undead all around her as the camera draws back to reveal the true devastation of Umbrella’s actions. That ending haunted me for years after I first saw it. Anderson has replicated it throughout the franchise of films he's produced and directed, but none carry the punch the original still has.

For all it gains with its reputation as a survival horror or action horror game, the Resident Evil franchise is also a puzzle game, like most third-person games of its time. Even without an explicit interest in the greater story of Remake or the franchise, much of the player's engagement is bound up in solving simple puzzles that break up the monotony of shooting and burning zombies or bio-monsters.

To some degree, Anderson's Resident Evil attempts to pay homage to the puzzle aspect of the gameplay in its whodunit subplot. Alice and the audience are trying to figure out why everything happened as it did in the Hive. But instead of files and booby traps, we get stylized music-video-esque flashbacks.

Conclusions

For all the accolades it received, Remake suffered a fate similar to Ubisoft Montreal’s Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, as neither made the money Capcom was hoping for. Considered a financial failure, the partnership between the corporation and Nintendo soured.

Remake's failure is often cited as the reason Resident Evil 4 veered toward action horror and away from its apparent Haunting Ground architecture. Mikami, however, argued it was a "natural inclination" for him by that point in his career. The mood demos for early Resident Evil 4 have been deified so much that this isn't typically considered.

On the opposite end, for all the snark it got (and still gets), Anderson's Resident Evil was successful enough to earn the film a sequel and a dedicated audience. From here, the relationship between films and games becomes intertwined in this symbiosis that plays off each other, influencing stories differently. The promotional circuit for the film marketed Remake on the GameCube, with Jovovich and Anderson playing the game at least once at a public appearance.

As games became more action-oriented, so did the films. The more ridiculous aspects of the games (superpowers, clones, gun-fu, etc.) eventually made their way into the film franchise, pushing it further and further away from the otherwise “grounded” approach of the 2002 film. As the protagonists experienced power creeps, the plots constantly relied on world domination. The general lack of conflict or peril characters like Leon or Claire faced in the Capcom-produced direct-to-DVD films (Degeneration, Damnation, etc.) matched the superhuman Alice had become by Resident Evil: The Final Chapter.

Where the films maintain some level of tongue-in-cheek, I feel like Capcom's compromised desire to match the tone and market gains of Call of Duty cost the games their sense of humor. The games re-imagined themselves as darker and grittier horror games that worked back up to on-brand goofiness, while Anderson’s franchise of Resident Evil films stayed the course of absurdity with the same number of story revisions as the games. To a large degree, I think that’s why they were always a hit with international audiences.

Remake and Anderson’s Resident Evil were a big part of why I became enamored with the series. What started as something I saw my older siblings playing occasionally became a genuine interest, and my gateway was Capcom's marketing push for newcomers. At the same time, I saw in-store posters for Remake (Jill being choked by a zombie), magazines bolstering Milla Jovovich, and talking about "Resident Evil: The Movie" finally hitting theaters.

Remake is no longer trapped in the reliquary of the GameCube, with digital downloads making it far more accessible for newcomers. Its reputation as one of the great remakes of the gaming world has only grown, and it's not undeserved. Time and space have been kinder to the original Resident Evil film. Obnoxious "No True Scotsman" takes are no longer the norm, and I'm glad for that. But depending on where you fall on the age scale, Anderson's take on the franchise will always remain a blight for some.

Remake and Anderson's Resident Evil are Capcom's franchise at its best and, honestly, most inventive. They set the tone for the franchise, financially and aesthetically. It’s wild to think both existed simultaneously.