Prince of Persia's Accessibility Is Inaccessible to Some

When accessibility becomes commoditized

At the Game Awards, it was easy to blink and miss the award for the best accessibility feature in a game for 2024, with the winner going to Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown. You may be hard-pressed to know what it did, as the award show did not highlight any of the accessibility features being nominated. Although I completed the game, I’m hesitant to call it the best example of accessibility in 2024, despite understanding the developers’ intentions.

Picture-in-platforming

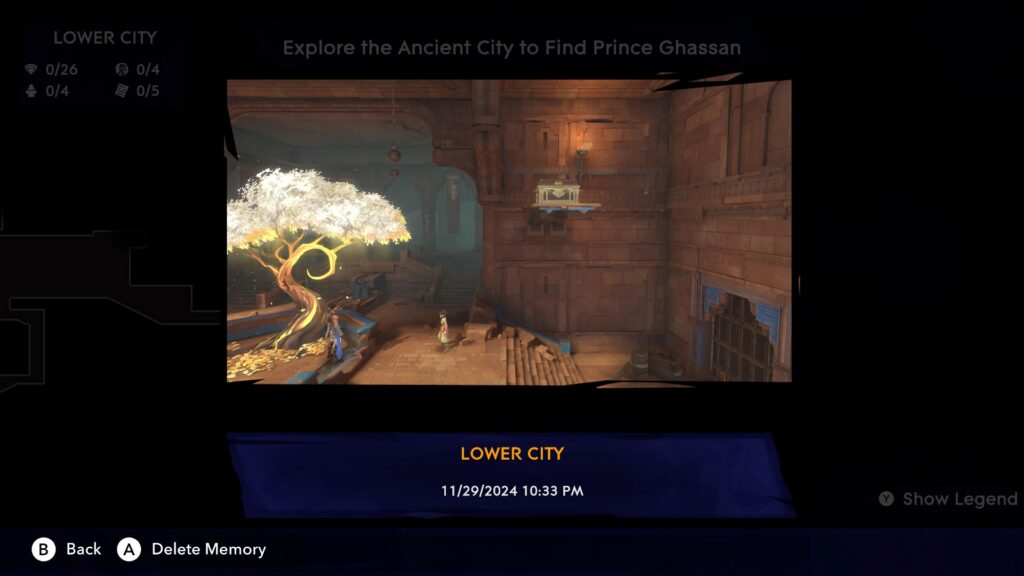

This will not be a review of the entire game, but I want to talk specifically about the use and implementation of its most advertised and original accessibility feature: the ability to create in-game screenshot notes. The design aimed to provide players with the means of recording a room to either mark notes for a puzzle, needed powers, or an item that they need to come back to. PC fans could simply use their digital platform of choice to take screenshots, but this was the first time such an option was available to everyone—including console players.

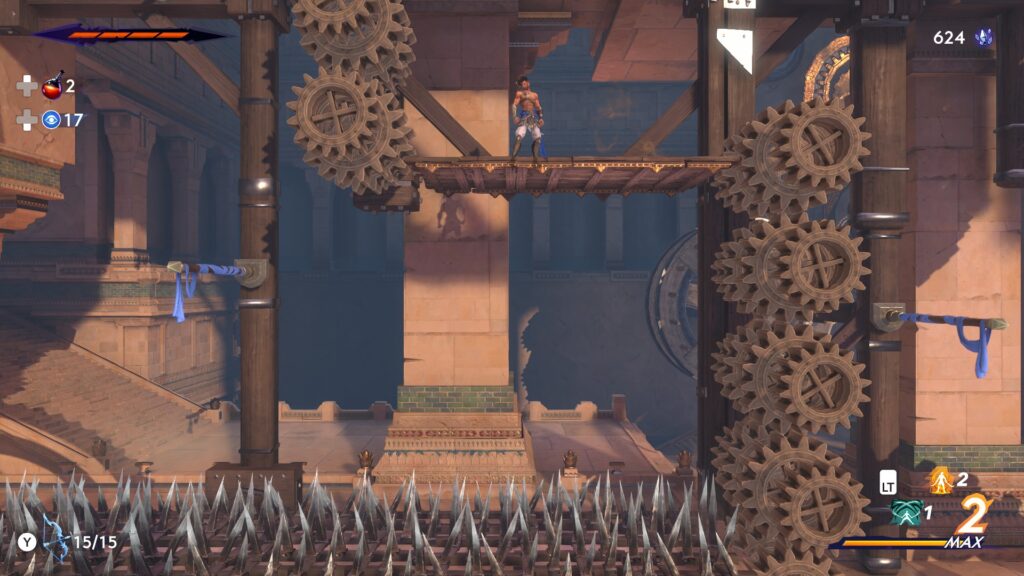

Part of the problem with metroidvania and open world design is that it can be very easy to forget where the player needed to use an ability or missed something. Going through La-Mulana, a feature like this would have been very useful.

With that said, what’s my problem with it? It’s not that the feature is bad or doesn’t provide utility, but that it became a part of playing the game regardless of whether you want to use it.

Accessibility tokens

Good accessibility features in games are those that are layered on top of a balanced experience and provide the means for more people to experience a game who may not have been able to do so without it. When you look at titles that use assist modes as an optional feature, the game in question tends to be unbalanced, or the experience is not predicated on these features.

In my opinion, the problem arises when games, seemingly balanced or ignoring balance, use accessibility features as band-aid fixes for poor accessibility design. This isn’t a problem if the player can just disable it or ignore it with an options tweak. This differs from having a sandbox or free play mode in survival/crafting games, as those games draw an audience of people who just want to use the tools to create. One of my most controversial points that has earned me ire from people is that accessibility features do not fix a game’s problems. Time and again, I’ve observed accessibility features failing to save games from plummeting player interest and high churn rates, and Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown is no different—more than half its Steam players quit before reaching the one-hour mark.

I was surprised to discover, while playing the game, that an accessibility feature functions as a consumable resource.

The player only has a limited number of “pictures” they can take before they must delete some. This left a bad taste in my mouth as it reminded me of when NetherRealm implemented the option for “easy fatalities” that allow someone to push just one button and perform the character’s fatality. On paper, this sounds great and a way of providing accessibility for someone who can’t remember those combinations or struggles to put them in...right? Instead, it became a consumable resource that players could spend money on to gain more tokens if they run out.

Returning to Lost Crown: As a reward for completing some of the harder and optional platforming challenges, it was possible to find more memory shards/screenshot charges. This theory sounds acceptable, but it ties the game’s challenges and reward system to an accessibility option. If someone doesn’t use the feature, tying a challenge’s reward to it feels like a slap in the face for someone who just did all that and is not getting rewarded for their effort.

Accessibility should not be a “consumable” or a resource; it should always be available if someone needs to use it. Therefore, game balance and design should not depend on its use if someone doesn’t want it or need it. For an expert metroidvania fan of Prince of Persia, or an expert fighting game fan for Mortal Kombat, these options mean nothing to them; they will not need them to play. However, for someone who genuinely would need or want them to enjoy the game, tying them to a resource isn’t right. Consider the outrage if a video game gated colorblind mode behind an experience point cost and subtitles behind significant gameplay progress; accessibility advocates would be up in arms.

When accessibility works

If your game’s design is being balanced under the assumption that people can just use an accessibility feature to “fix” any problems, you’re going to find people quitting your game out of frustration. They may not know that the option exists, or feel that the game is not providing them with a carefully crafted experience. The cases when I had to use an assist feature or accessibility option to finish a game did not make me appreciate their inclusion, but made me wonder just how many ended up quitting the game before they even knew about those options.

This feature improved accessibility in Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown. However, the game’s demanding pace and level design caused significant accessibility issues (a topic requiring extensive explanation, explored later). I haven’t played it yet, but The Last of Us 2’s extensive accessibility options, offering fine-tuned gameplay difficulty instead of simple presets (i.e., easy, medium, hard), are great and also featured in The Lost Crown.

Remember, if someone finds your game bad, annoying, or poorly designed, no amount of accessibility or approachability options is going to save it, nor is there a perfect itemized checklist of all options that fits every game. Accessibility and approachability work best when built on top of a balanced game as a way to open it up for more people to enjoy. This requires the designer to understand who the market is for their game, and what pain points or frustrations exist for newcomers.

It’s not about simplifying the game; it’s about enabling a grandmaster of games to enjoy your title their way, while also allowing someone who finds it challenging to experience it on their own terms. However, treating accessibility and approachability options as duct tape for your game’s design will lead to more problems. This frequently causes designers to overlook fundamental problems or player frustrations, leading to churn. It’s your responsibility to deliver a well-designed title for players to enjoy, not to leave them with the task of fixing it themselves.