Playing the Feminine

Deconstructing the stereotypes

For as long as virtual guns have existed women have wanted to shoot them. Despite the history of video games involving a lot of men calling the shots in play spheres, development teams, and as critics, women and gender-queer people have been engaging with games’ more perceived masculine elements of destruction, conquest, and embodying characters who never reflect on how these themes make them feel, since the beginning.

Upcoming game Incolatus is one such example. Described as a “Y2K girly-pop arena-style movement shooter” players shoot robots with hearts instead of bullets to re-imbue the world with love. Funny Fintan Softworks’ tongue-in-cheek approach subverts the typical masculine/feminine binary by mixing together customisable guns and frenetic old-school mechanics all within a neon-pink oasis.

This genre stands in stark contrast to the stereotypes attached to feminine play: wholesomeness, cottage-farms, cooking, dressing up, befriending animals, talking about feelings. While these elements can be taken up seriously as feminine there is a large history of prescribing them as the only type of game women can play. Researcher Stephanie Harkin contends “there are girls who are interested in horror and the macabre and it would be a disservice to only focus on things like sentimentality and child friendly themes."

Femininity has deeply historical ties to gender that still persist today. Because it has been relegated to the sphere of women so comes with it a lack of critical attention, and a large culture of undervaluing and infantilisation. However, femininity can be taken up, enjoyed, and critiqued by anyone, regardless of gender, which is the larger message of the upcoming exhibit Feminine Play.

So what exactly is feminine play? In the spirit of play, which is about setting up, adhering to, and sometimes dismantling rules, it’s much more fun to ask: how can we play with femininity?

Girl gamer (setting the rules)

One of the larger myths of our time is that women do not play video games. Harkin believes there is something about the culture of games which may play a part in this understanding, not only because some game spaces can be unwelcoming, but also because the deciding factor for who a real gamer is seems dictated by certain structures. Harkin says the word gamer “is very contested, and not many people identify as gamer because it's got a bit of patriarchal weight to it.” But whether women are logging away hours of game-play every night, playing mobile games on the way to work, or dabbling in The Sims every now and then, they “probably spend just as many hours as the guy that buys FIFA once a year.”

We cannot overlook experiences in spaces such as massively multiplayer online games with voice-chat function. Marketing manager of Hipster Whale Katie Roots reflects on her time playing these games:

"I was not an official gamer, I wasn't allowed. I was talked down to or incessantly quizzed… the verbal abuse I would get… but we [women] were there the whole freaking time. Dudes were just assholes."

Many women and gender-queer people will have memories of either being bullied or excluded for their early interests in video games. I was lucky enough to grow up around the boys in my family who love games so much they were simply happy to have me as another player, but the experience was quite different outside of my familial settings. Curator Jini Maxwell reflects on their childhood: “When I was a little kid, I was becoming aware that the expectations around my behaviour were gendered in a way that meant that video games was a weird thing for me to be doing.”

Similarly, I remember children across all genders questioning or mocking me whenever I brought my Game Boy Colour to school, which is why I suspect it took me so long to find fellow girl gamers—everyone had the sense it was an embarrassing secret to be kept, or even worse—that it made you a ‘pick-me’.

Yet women and gender-queer people are persistent with their love of video games. Maxwell reflects that “there have been women excelling in absolutely every area of games, from making them, playing them, to breaking them, to doing weird things with them, for as long as there have been video games.”

There was a fascinating wave of the Girl Gamer in the 1990s, where gaming companies began large marketing campaigns towards girls and women. It inadvertently meant they (mostly men) were dictating to the world what type of games girls should be playing, and therefore further solidifying the ties between womanhood and femininity.

However icky it was to be told what to play, many look fondly at that time as something which at least brought girls to the table, even if it was so they could become paying consumers. “There was attention to actual innovative gameplay mechanics and a lot of freedom to experiment for these games made for girls because they didn't really have a clear idea of what they were doing yet,” says Harkin.

Even though we were being told what femininity and girlhood was supposed to be, at least there was a conversation in the first place. As Maxwell says “Girl Gamers is quite specifically a market, rather than being representative of how femininity is expressed through play in any kind of meaningful way.”

Serious femininity (appreciating the rules)

Femininity can look like a lot of different things, particularly in games, and for that reason it makes it difficult, and arguably unnecessary, to strictly define. Harkin has a history of research in girlhood and games, but she finds the lens of femininity allows her to explore more because it isn’t necessarily attached to gender:

"I think femininity can come out in lots of different ways in games, and so I'd be hesitant to describe it or define it too strictly, because then I feel like you're just putting it in a box."

Game studio Dinko are about to release Candy Castle, based on a game-jam of this year inspired by the Women’s Weekly cookbook. The studio, particularly developer Olivia Haines, is known for her hyper-feminine style of pastel pinks, cuddly creatures, and fairies. In her most-viewed TikTok video is footage of her upcoming game Surf Club with the caption “The feminine urge to only make video games as a form of self expression and make no effort to appeal to gamers.” Haines is someone who has a deep care and respect for the feminine aesthetic.

Surf Club is the type of game that may have historically been deemed only for women, and as an extension, not real gaming, but we can celebrate this style of femininity alongside others. Harkin is witnessing a change in the local games industry which steers away from competition and violence, while also contending that it is worthwhile “to push back on the wholesome cottage core association with femininity.” Nevertheless, she believes “if you find pleasure in it that doesn't mean you're suppressed or naive. We can be critical of it at the same time.”

Experimentation and subversion more frequently happen within the indie game making space, particularly because more women and gender-queer people populate this space compared to large studios, and because they have more freedom to explore game elements which are close to them.

Mystiques is an upcoming “whimsical haunted antiquing adventure game” by Lemonade Games. In response to how the game plays with the idea of femininity they say:

"We wanted to make a game about young women and friendship that doesn't shy away from the shadow parts of ourselves—-being selfish, materialistic, lazy, angry and rude. These are all valid parts of the human experience and oftentimes, parts of ourselves that we are encouraged to suppress and feel shame around."

Lemonade Games reminisced on the wave of '90s Girl Games, from the Barbie franchise to The Sims. There are many who have been inspired by these early iterations of feminine play, but this does not mean people have simply accepted what the larger structures have told us. “Women or gender queer people are not blindly eating up what the patriarchy has packaged as femininity, but can both play and enjoy a game with these things in critical ways,” says Harkin.

Just as earlier game experiences have changed the indie game landscape, undoubtedly it has seeped into triple-A titles. Harkin describes how collecting gear, skins, and customising avatars in games like Fortnite and Apex Legends is analogous with feminine play traditions like dressing up dolls. The blockbuster games of our time are now imbued with mechanics around social bonding which change gameplay experiences. How the character Kratos in God of War takes on a care role, the history of Yakuza games incorporating dancing, singing, and now island management elements, and even what is deemed by some as the best game of 2023, Alan Wake II, which includes a musical number. Not to mention the number of female protagonists who have attributes across spectrums of masculine and feminine.

A clear example of player engagement with femininity was a moment in time when many cities went into pandemic-induced lockdowns. Harkin reflects “during Covid Animal Crossing: New Horizons came out the same day as Doom Eternal, and I think it was the start of lockdown, and people just weren't feeling a game like Doom."

The majority of people I knew at that time were playing Animal Crossing, regardless of gender or perceived masculine or feminine interests. That was a clear time when people had a desire to engage with feminine gaming aspects; slowly building up a town, sending your friends letters and gifts, visiting their islands. Harkin believes “a lot is owed to the '90s Girl Game movement, these legacies of feminine play that were once tied into gender trickled out into all different kinds of games.”

Queerness (breaking the rules)

Another aspect that Harkin enjoys about looking at femininity is that it allows her to explore queerness as it relates to gender binaries. “These genres aren't labeled for genders, and so even though they're really popular with women, there are people who can and who do engage with them and appreciate them. Femininity and queer communities have always been really important in terms of activism and pushing against binary gender stereotypes.”

A poignant example is one of Maxwell’s early play moments which, although was designed to be inclusive, brought up tricky questions about their own identity:

"I really remember when Pokémon Crystal came out and there was a boy and girl option. And my funny experience is that I was kind of confronted by it, because I had never thought of the main character as anything. I was like, but that's me, I'm just a little guy. Suddenly I had to think about their identity."

Whether play is happening within a video game or on a playground, it is one of the dominant ways of making sense of the world and our position within it. With this in mind, Maxwell believes that “if you place strict gender limitations around what people can imagine and what space they can play in, it limits how they imagine and see themselves in the world context too.” As one of the largest cultural mediums of our time, video games also have somewhat of a responsibility to offer up various modes of engaging with the world. As Ruby Quail aptly says: “the world is becoming a lot more like a video game and video games are becoming a lot more like the world.”

“Femininity is a really loaded term,” says Quail. As an artist, designer, and technologist with a background in industrial design, Quail is interested in how one communicates complex social ideas through play, whether that’s a video game trying to tell story or a physical space conveying an idea.

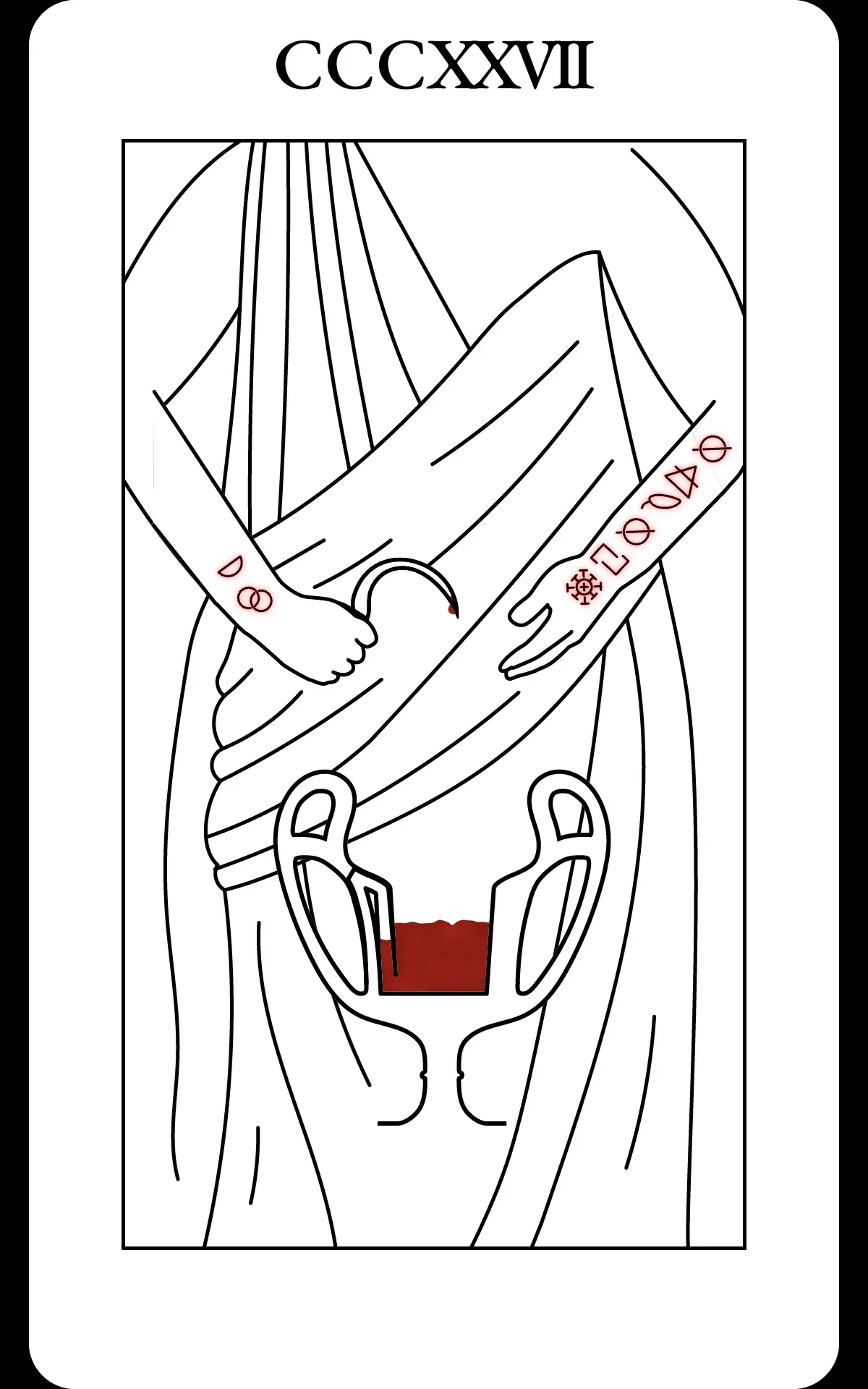

Her interactive installation Thou Dost Bleed asks the question “what is the requirement of womanhood?” As a trans woman, Quail often has this question front of mind and what it means in terms of others’ expectations of her. She has created a shared ritual of users donating suffering to a fictional trans person by asking them to add blood to a virtual cup which continues to empty out, and so, will never be full.

"There's a cliche among transphobic feminists that trans women can't be women because they don't bleed, they don't have menstrual cycles, and that that kind of suffering is a prerequisite to womanhood."

Quail is not simply interrogating the rules around femininity, but the so-called rules of a game as well: can something that not cannot be won, if the cup can never be full, be called a game? And if so, is it one that is worthwhile to play? For Quail she is happy that as a gender-queer person she can “find femininity outside of what the expectations of the space typically are.”

The term femininity is just as complex and loaded as the notion of play; as something that at once feels casual, frivolous, and separated from the world, and that can also change the social and cultural ways we understand our experiences of the world. As these works show, playing with femininity does not mean to accept the ways in which it is packaged and sold to us, but to make do with it in our own unique ways. Whether that’s in the form of a bubbly shooter game, hyper-feminine art aesthetics, writing nasty characters to love, or using blood sacrifice to question the very notion of femininity. As Harkin says, “we're embracing that on the one hand [femininity] is devalued as infantile, but also embracing the silliness because they're games - it's play.”

The creators mentioned in this article will have works showcased in Feminine Play, a public exhibition running from October 4-18 as part of Melbourne International Games Week. Feminine Play is created from the research of Stephanie Harkin and curated by Xavier Ho, Mahli-Ann, and Jini Maxwell.

This story was commissioned by SUPERJUMP with support from Creative Victoria.