Omocat's Comforting Fantasies

Omori's complex tale expands the world of its source material

If you were on Tumblr in the mid-2010s, you probably saw this comic:

Omocat's Pretty Boy hits pretty much every Tumblr sweet spot there is: 1) cute, 2) manga, 3) violence, 4) gay. It's the story of an unnamed Jock who bullies the titular Pretty Boy and then, slowly, falls in love with him. The story climaxes when Jock saves Pretty Boy from homophobic violence, symbolically overcoming his own bigotry. The two live happily ever after: they get married, adopt a child, and live their lives peacefully until Pretty Boy, still pretty as ever, passes away with a smile on his face.

Pretty Boy is always smiling. Pretty Boy is forgiving. Pretty Boy is sweet. Pretty Boy's beauty does the talking for him, implying his virtue without detailing it – it means we can see Pretty Boy reading an explicit BL manga without ascribing to him the impurity of sexual thoughts. We know nothing about Pretty Boy except that he is pretty, that he is a boy, and that he is gay. He is the blank canvas onto which Jock’s character arc is projected.

I don’t mean this as a negative per se. Pretty Boy is a short comic, so there isn’t a lot of space to draw out a complex narrative. Its storytelling is visually economical and emotionally appealing. The page on which Pretty Boy gazes at Jock playing football, and Jock blushes as he realizes he’s being watched, is what falling in love feels like – a sharp, distilled moment of thrilling visibility.

In other words, Pretty Boy is a triumph of aesthetics over character and plot. Its story is familiar and its characters are predictable, but its execution is appealing. Its sudden shocks of violence and sexuality lend it a lightly transgressive edge, but it’s more interested in providing comfort rather than psychological depth.

Practically everything I’ve said so far can also describe Omori, Omocat’s 2021 RPG.

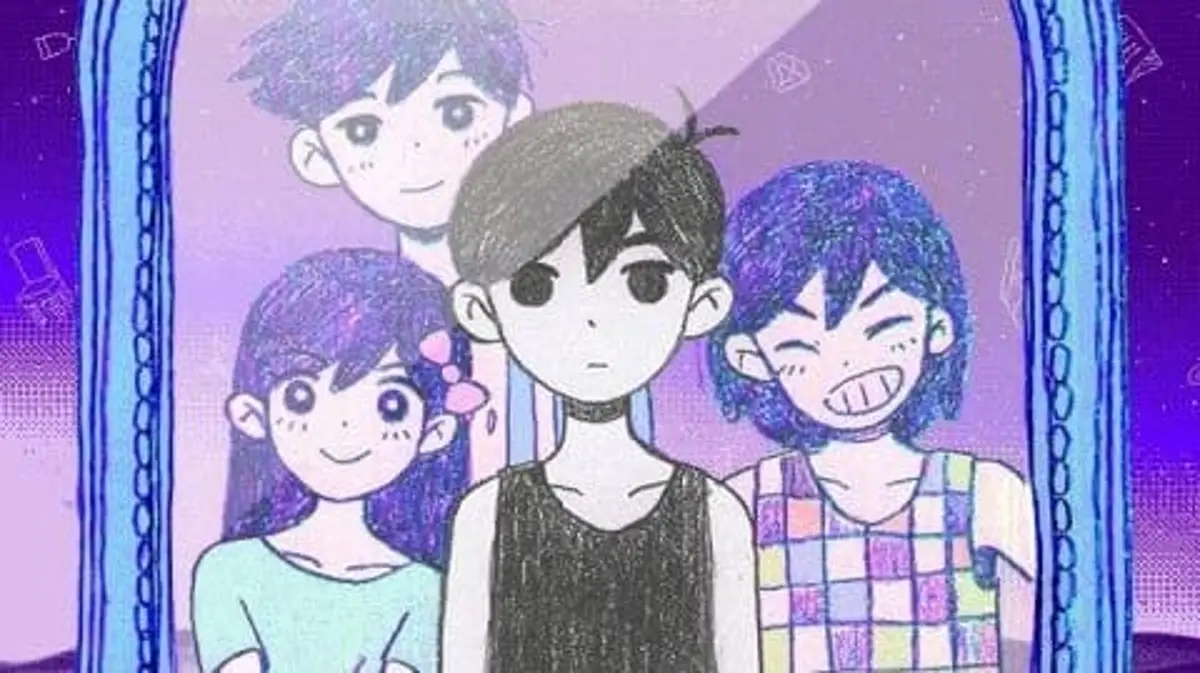

Not in terms of plot, mind you – Omori is not interested in romantic love. Instead, the game attempts to tell a complex story about mental health. You’ll split your time in Omori between Sunny’s imagined world – a quirky, lightly sinister land called Headspace – and his real-world home in Faraway Town. Each morning, you’ll wake up in Sunny’s bed. Each night, you’ll close your eyes and dream of Headspace.

A two-worlds gimmick is a classic gaming trope, and Omori’s use of it is smart. Headspace and Faraway Town resemble each other enough that the differences feel meaningful. You’ll notice that Sunny appears in Headspace as an emotionless child named Omori, and that all of Sunny’s friends and acquaintances in Headspace have older counterparts in Faraway Town too. All of them, that is, except for one: Sunny’s older sister, Mari.

In Headspace, you’ll find Mari stationed on picnic blankets throughout the world, acting as the game’s save point. She is always kind, always knows the right thing to say, and is always equipped with delicious snacks. Her shallow characterization and welcoming presence make her Omori’s closest analogue to Pretty Boy, with one major difference: Mari is dead.

In the game’s first half, we’re told that Mari died by suicide. As Sunny reconnects with his old friend group in Faraway Town, you see that her sudden passing splintered their relationships, leaving them with lingering trauma and grief. This felt real and sensitively rendered, and Sunny’s consequent retreat into Headspace made sense. Characters in Headspace are one-dimensional by design; we don’t see them as they are, but as Sunny wants them to be, based on his idealized memories. While Headspace can be gruesome, it doesn’t challenge Sunny’s perception of himself.

This is expressed through Headspace’s focus on RPG gameplay. The traditional explore-battle-explore rhythm of these sequences feels hypnotic and soothing. As in any RPG, the repetitive act of grinding and experience-gaining is a playable metaphor for the party’s growing connection with each other. But these are not real characters, nor are they really expressions of Sunny’s personality. They are figments of his imagination, created specifically to comfort him. We integrate ourselves with the aspect of Sunny’s mind that exists to coddle and reassure, to protect him from his uncomfortable feelings.

While this dynamic lends the game’s horror sequences a jarring edge, it also means that its scarier moments register as the exception, instead of the norm. You will spend much more time in Omori fighting turnip-shaped enemies and pursuing sidequests than you will uncovering the mysteries of Sunny’s psyche or reeling from its scares. The game’s cozy RPG systems strain noticeably against the urgency required of horror.

But for most of the game, I didn’t mind. When the game seems like it’s about Sunny’s grief and anger towards Mari, it feels like the time spent in his mind is warranted. He would have to make peace with these feelings to return to the world, but that process would be uncomfortable and time-consuming; it makes sense that he would dawdle inside his own fantasies. But then the game throws in its final plot twist and the whole experience falls apart.

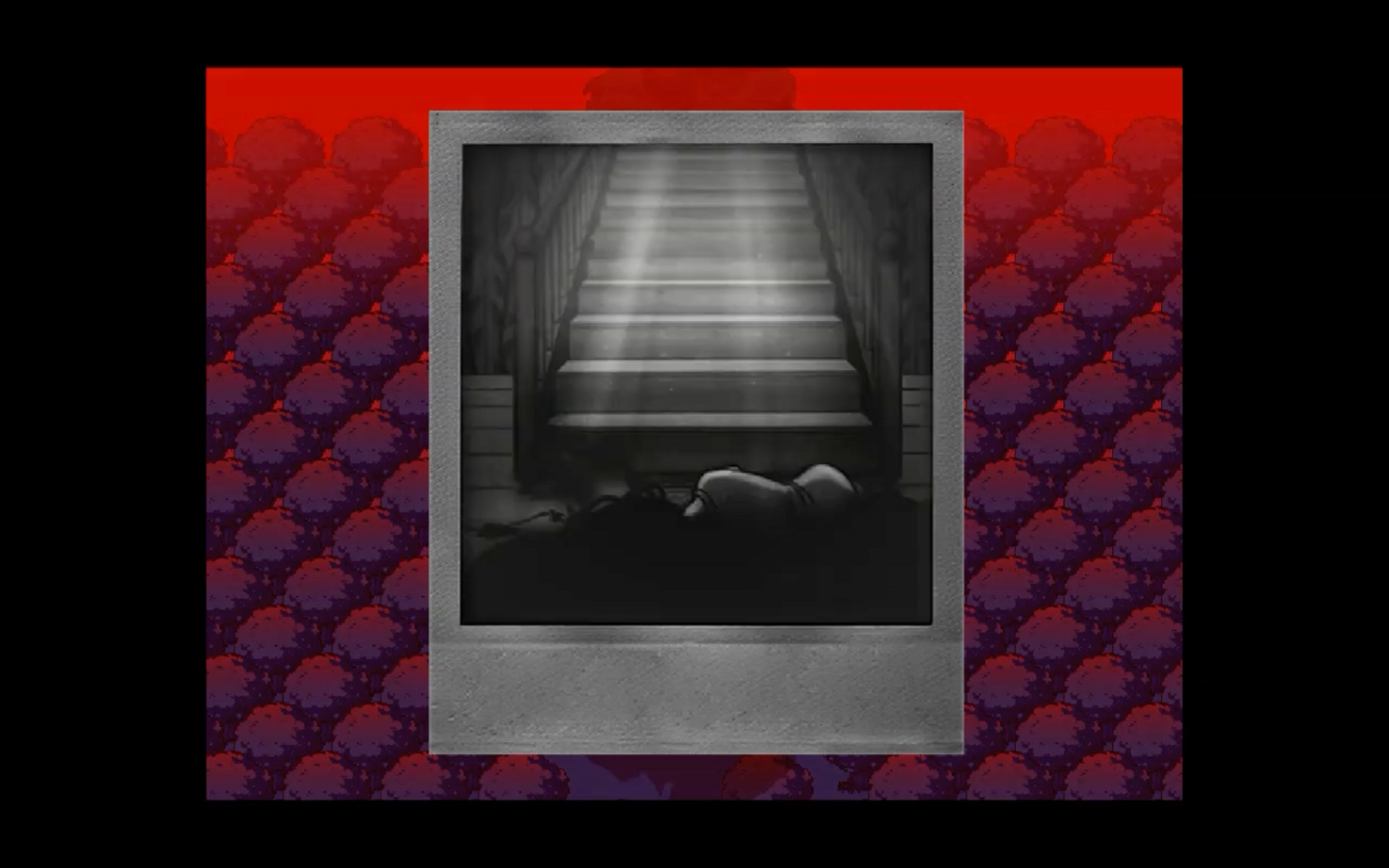

You see, Mari didn’t actually die from suicide. Instead, Sunny accidentally killed her by pushing her down the stairs in the heat of an argument. Basil, who witnessed the incident, came up with the idea to stage the death as a suicide by hanging her body from a tree in Sunny’s backyard. Sunny's withdrawal from his friends wasn’t just because of his grief, but because of his guilt.

This twist not only strains credulity, but it completely reframes the rest of the game. We are no longer playing as a lonely boy who wants to reconnect with his friends because he misses them, but as a lonely boy whose desire to rekindle his friendships comes from an extreme need for redemption and salvation. It makes our actions in the game feel incredibly selfish.

To make this twist workable, Omori manipulates our perception of Sunny with ruthless efficiency. We spend most of the game as the emotionless, childlike persona Omori, who exists within an imagined world that was specifically created to protect Sunny from the truth, and whose youth makes the scarier elements of the game feel more dangerous.

The horror segments are cordoned off from the RPG segments. When the game wants to scare us, it takes control away from us, as if the horror is an external presence rather than an intrinsic part of Sunny's daily experience. And unlike many games that explore similar psychological themes, like Silent Hill 2 or Signalis, Omori is an accessible and easily played experience. It doesn't express its conflict through gameplay systems, but through imagery and aesthetics. These techniques preserve Sunny's sense of innocence and victimhood. So when we grow attached to Sunny, it’s not despite the tragedy in his past. It’s because the game is lying to us about who he is and what he's done.

And by spending time with Sunny’s friends during the real-world segments in Faraway Town, we are in turn lying to them. After the final boss battle, if we’ve achieved the True ending of the game, Sunny wakes up and faces his friends, saying “I have to tell you something.” Before we can see their reactions, the game cuts to credits, soundtracked by an upbeat chiptune track. The actual truth and its repercussions don't matter; the only thing that matters is our ability to speak it as if confession and forgiveness are the same things.

That’s not to say that these emotionally discordant notes have no value, just that the game only seems partially aware of its own contradictions. There’s a sense that Sunny’s suffering cancels out the damage that his actions caused, and that by accepting his past, he frees himself from his suffering and guilt.

The game has worked so hard to infantilize Sunny that there’s no space to meaningfully reckon with how his actions have affected the other people in his life – literally, as the game cuts to credits before we can see his friends’ responses. By extension, we’re robbed of meaningful role-playing opportunities. We can’t play as a version of Sunny who attempts to engage with his past honestly as he moves forward, nor can we imagine a different version of Sunny who’s been warped by his actions. Sunny’s past is presented as something that passively happened to him rather than a sequence of events in which his choices mattered.

In its way, this is a comforting fantasy. It releases Sunny from the burdens of guilt and shame, because within the moral schematic of the game, he's already experienced enough pain – similar to Pretty Boy, in which Jock’s decision to put himself at risk cancels out his homophobia. It’s not that Sunny’s decision to face the truth is a bad one, and it’s not that he should live in shame for the rest of his life, it’s that forgiveness is something given as a gift, not something we can earn by suffering enough.