Nobody Wants To Die and the Unsung Beauty of Expiration Dates

Investigating the implausible dream of immortality

There’s a popular fact that’s thrown around, about how our skin cells are shed every day, and within a month, something entirely new takes its place. As we grow older, it takes longer for this invisible renewal, and even further, we see signs of this slowing down. Our change no longer happens behind our backs. Suddenly, there are liver spots and wrinkles, and when you look in the mirror, you’re visibly not the same person. You start to misplace things, names get jumbled in your head, and words escape your recall.

The process of aging is something frightening that artists across time have flitted around and played with, trying to escape it through fiction. Aging is the slow approach of the end; it is letting the grim reaper into your home and befriending her. No wonder so many people substitute for a better way out through fantasy: the Holy Grail, consciousness transfer, all the whimsical imaginative ways just to replace the reality of your body and mind betraying you, which is, put another way, you failing yourself.

Everything has a best-before date, an optimal timetable without which things deteriorate and cease to be what they once were. Without preservatives, foods decompose, and like microbes that eat at your favorite cheese and turn it into a moldy mess that smells, human beings face the same fate. We too become spoiled meat and our thoughts turn twisted, a spiral wool of words in our heads that become unfamiliar to us. Internally, the brain eats itself to function properly. It’s something normal and isn’t as dysfunctional as the statement sounds, but eating too much may cause cognitive decline or even schizophrenia. The brain uses one of its dedicated cells to consume other cells, neurons, or synapses in order to shape it. Like the snake that eats its own tail; behind what we consider to be our immutable identity is the basis of our self, constantly changing through self-consumption. The human brain changes constantly and shrinks with age. It atrophies, and so do we.

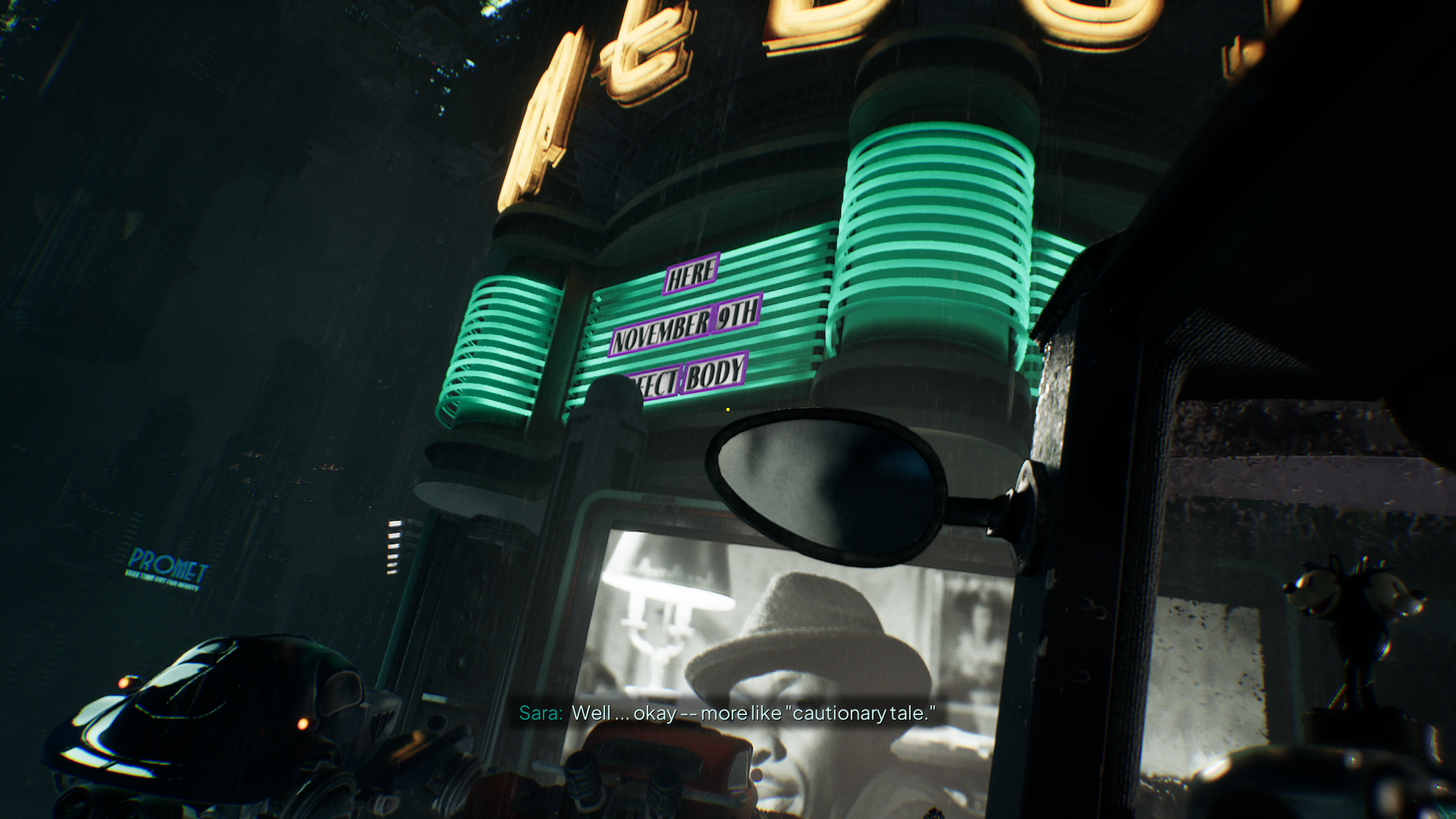

What becomes of our memories, our whole context for being, once it is all stripped away? In Nobody Wants To Die, memories become mere projections, distorted by present fears and diverted regrets. A game inspired not only by the visuals but also the themes of influential cyberpunk media such as Blade Runner and Altered Carbon, what starts as a murder mystery quickly becomes an exploration of immortality. Set in a world where bodies are a commodity, exchanged property, the idea of immortality is sold at the price of sanity. Here, nobody dies permanently and consciousness can be transferred from one flesh to another, even from a dead body. The catch is that you must have sufficient money to afford it. The story begins in a flying car, your dead wife sitting next to you, speaking. You’re watching a drive-in movie, an old black-and-white noir detective flick. This sets the tone for the next 5-6 hours. Shortly after, as always with these things, there’s a dead body, and it starts from there.

Like the snake that eats its own tail; behind what we consider to be our immutable identity is the basis of our self, constantly changing through self-consumption.

What if people live forever?

In this speculative future, Olympus is a highrise where the torch that never goes out is a lit room for the endless debaucheries of deities. They inhabit the only place where clouds can be seen, up above the sheet of smog. This is your first crime scene. These gods are immortal (not anymore) humans who only possess power because they are policymakers; their miracles are chic patents that distort human rights. By the end, you realize the deicide is closer to suicide, as the gods killed themselves with their own unsupervised policies like a sun burning out. Turns out, the murder weapon was an expiration date, and immortality itself existed on borrowed time.

For most of the game, the other characters you meet are either dead bodies or voices in your ear. You can only get to see them by reconstructing the crime scenes in a style reminiscent of the Batman Arkham series, getting to know them from their corpses, and then backward in time. Only later near the end do you get to meet some characters face to face, where they’re always framed as enemies at first. The protagonist, James Karra, is a paranoid tortured soul, who attempts to detect everything except the one thing haunting him: his past and the reason for his loss. He is so consumed in the narrative of the solo hero detective, he misses the possibility that he’s compromised.

From the protagonist’s narrow perspective, everyone else is in on a conspiracy to hide a clear-cut murder case. Set in the shoes of Karra, the player shares his point of view. After all, he’s the drunk detective trying to make things right, the lowly underdog against the giant corporation, or at least he appears to be. But he’s not. He projects his grievances outward to the world. The player too can be lulled by the familiar trope, unable to see the bigger picture, the context of the world they are in, and the bigger structural issues that tower over the individual. If the player fails to make the right call, they will doom Karra to a life of purgatory, of immortality in a freezer. On the other hand, if they break the spell of the drive-in narrative and wake up to the larger context, they get to give Karra his heaven off the earth.

What is the cost of forever?

What many in the past idolized as state-of-the-art saviors - artificial intelligence, electric cars, and neural interfaces - in hindsight may harm as much as they help. Rapid invention without adequate forethought about continued consequences is why some champion AI regardless of its ethical ambiguity. Most of these futuristic novelties are elevator pitches that sell themselves as the final product. Air pollution and lithium mining aren’t in the fine print, but servers need to be cooled for AI usage and batteries need to be made for cars to run. Every give has a take, just like immortality has its own price. A copyrighted body of work being exploited is one thing, but when your biological body is not under your own authority, just part of an assembly line for consumers, is immortality even worth it? It’s ironic that in the world of the game, trees, living beings that are known for their length of life, are replaced with faux holographic ones, to fake eternity.

Another unintended effect of immortality is what it does to memory. The more you remember something, the more it changes. In a life that lasts forever, how many things get retroactively altered through reflection? James Karra’s obsession with his dead wife changes her, removes her agency, imbues her with the spectral power of haunting, and creates a killer where there is none. The murderer in this murder mystery is a lot of things: it is time, it is memory, it is the desire for humanity to live indefinitely, and the pressures of capital to do so. After all, heaven is for those with no means for the present. And hell? Hell is endlessness. It is immortality without consistency, where time becomes a trap, a life where you slowly lose everything, from the meaning of life to yourself.

Everything from the past gets recontextualized in the future. Even Dali’s famous painting The Persistence of Memory gets redefined with the movement of art and through the lens of Dali’s new experiences. The world spins, and the painter’s opinion of the piece changes with it. He reinterprets his classic two decades later, with The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, having the contents of his original painting deconstructed, and split into pieces. “Everything is suspended in space without anything touching anything,” it is said of the work. With the Blade Runner-esque flying cars and buildings that seem to have no end, skyscrapers that not only scrape the sky but take it over completely, the infinite possibilities of technology and the future disjoint our reality. In the end, nothing persists except change. The painting eats itself into bite-sized pieces. Even an art that lays claim to forever is rebutted by one that proves otherwise. As an artifact, a painting may conceivably last as long as there are conservators who keep it from breaking apart, but the opinions of the painter are not as permanent.

The more you remember something, the more it changes. In a life that lasts forever, how many things get retroactively altered through reflection?

What if people shouldn’t live forever?

What people want when they think of immortality is to be stuck in a photograph, living forever in a perfect moment, suspended, without thinking of dwindling resources or change. But moments pass, vignettes are part of a larger whole. So immortality isn’t the answer, as it extends, but not sustains. You can’t prolong a moment or the feeling of happiness, you just extend the life you’re living now, with moments that are still fleeting, and the happiness more so. “Whether you think of it as heavenly or as earthly, if you love life, immortality is no consolation for death.” What philosopher Simone de Beauvoir meant by this statement was that neither belief in an afterlife nor a legacy that outlasts it could replace the reality of endings. Life is defined by its limits, and there’s beauty in that, where a short time heightens what exists within those precious passing moments. Memory can stretch itself too thin, as it outlives its lifespan, and outstays its welcome. If those moments did not become tears in the rain, they’d be lost in a sea conflated with one another, endless, indistinguishable. People would be stuck in a never-ending twilight, gently losing reason. As nobody wants to die, the brain will eat itself, leaving nothing but vague imaginings of a memory or a faint recollection of a self.

What if the only thing that fiction provides concerning immortality is comfort by way of cautionary tales? What if the Holy Grail or consciousness transfer isn’t something that one should ever strive to achieve? Perhaps it is not a heaven that those fantasies foretell, but a hell. Nobody Wants To Die explores the fallacy of its title. Everybody wants to be immortal if they have their mental faculties intact; if they possess everlasting love, and enough money to sustain their living. But a life where everyone is as such would force decline upon the world they live in, and the scales once again tip toward decay. The game posits that immortality is not a sustainable utopia, and in comparison, maybe aging isn’t so bad. Maybe both a life and a love worth fighting for is one that ends. An expiration date does not diminish the value of a thing, it only means that it must be appreciated while the day is distant. Everything changes, so everything is worth cherishing.