NieR: Replicant and Experimental Narrative

The video game medium excels at defying expectations

There’s a moment in NieR: Replicant where the screen fades to black. Your protagonist and his sassy, floating-tome friend trek through the Forest of Myth, a surprisingly small area of deceptive verdant glory. Something is wrong with the dreams of the denizens — their dreams are infecting them, changing them, taking them outside of themselves and pushing them into another place. As Nier and Grimoire Weiss voice their disbelief at such a thing, a change occurs. The game begins to read you. Lines of white script scrawl across the screen and narrate the actions of protagonist and tome, much to the chagrin of both. They argue against the game, they assert themselves. They assure you, the player, that agency is being maintained even as this outside force attempts to arrest control of what is happening in the narrative.

Still, the screen fades to black. White lines of text continue to unfold across an empty black pane, and before you are entirely certain of what’s happening, the game has changed. It’s a visual novel, a minutes-long dive into an entirely text-focused narrative that takes the reins of the story and guides them into another, different form. The Forest of Myth is more than a diversion from the action combat and quest grind, it’s a diversion from the game’s genre entirely, plunging you into a moment of peace just long enough to afford a breath.

Defying Expectation

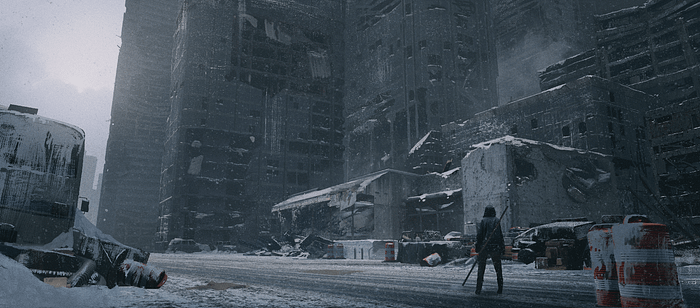

NieR has long prided itself on being different. Since its initial release ten years ago, it has garnished a reputation for being decidedly divorced of its RPG brethren. The story is non-linear, its focus pridefully scorning the typical mainstays of other games in the genre. From its harrowed beginning, NieR: Replicant is almost gleefully proud of what it withholds from the player. The mystery begins amidst a ruined city peppered with falling snow, a scene that unfolds between a brother and sister who look exactly like the brother and sister you will come to know in the game, removed by over a thousand years. The game tells you nothing. Don’t expect that to change.

NieR: Replicant pretends to be normal for as long as it possibly can. It’s holding in a secret, a sneeze, a deep breath. There is a deluge of backstory and worldbuilding behind the dam of its meandering fetch quests and back tracking and monster slaying, and it works the player just enough to tease out that maybe these things will be normal, that maybe this game is just another run of the mill action RPG, that perhaps what you experienced in the ten minute opening was only a glimpse into possibility.

As the game transitions out of its normalcy, something snaps. NieR: Replicant takes absurd joy in disregarding player expectation and manipulating the emotional line right up to the point that the tether of anguish threatens to snap entirely, and holds.

There is a moment in the game when Nier receives a letter and is invited to a mansion. He accepts, though there are dire warnings from both Kainé and Grimoire Weiss. From the invitation, to the threshold of the property that immediately dips us from full color to monochrome, it is obvious that something is amiss. The game again amends any expectation, subverting us by seamlessly transforming the adventure from action to forced camera angles à la Resident Evil. Like Spencer Mansion, the entire segment in Emil’s Manor is a grim reference to survival horror, forcing us to suddenly forget combat and explore a decrepit and claustrophobic environment on the search for keys and doors. Something is inherently wrong here, and as the game is want to tell us, the secret lab beneath the manor holds all manner of terrible secrets, keeping it a cousin to Resident Evil’s primary reveal. There is a horror here, and it is the first true grim reality we see played out against NieR: Replicant’s seemingly cliché narrative; nothing is as it seems.

Not Your Typical RPG

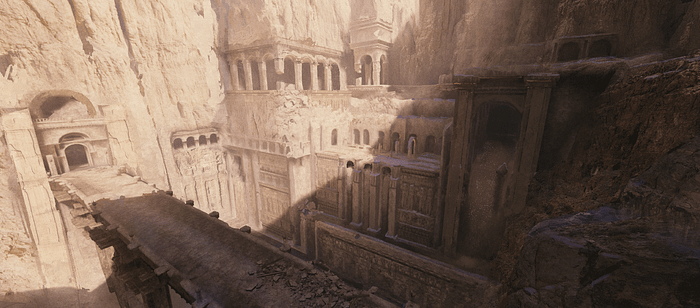

Taro Yoko, the enigmatic and camera-shy creator of the NieR and Drakengard series, seems to take some sort of perverse enjoyment from manipulating player expectation. The drive toward Ending B in NieR: Replicant is fairly singular, if you can forgive the endless monotony and fetch quests and backtracking. The story culminates in an ascension up the Shadowlord’s castle, a physics-defying apex topping the Lost Shrine, a tangled and ruined greenhouse that sits in the basin of a crater and is surrounded by toppled skyscrapers. To reach this point requires no end of monotony — the pieces of the key item required to ascend the Lost Shrine’s actual gate, the door to the Shadowlord’s Castle, are hidden behind convenient story beats. It is as if NieR: Replicant is painfully aware that it is in fact a story, that it cares more about serving its emotional banquet to the player then suspending disbelief to the point of crafting a believable story. The parts and pieces that form NieR: Replicant’s tangled narrative fit together so perfectly because it feels as though you are playing through a dream, and this dream is reinforced by the game’s subsequent repetitiveness.

Ending A, B, C, and D. While so described, none of these are true “Endings” so to speak, but arms of the greater narrative at hand. Ending A reveals itself in the way any RPG’s ending might — it’s dramatic and corrupt. It is only after clearing Ending B that the game begins in earnest, and you must start again — from the half way point, of course, where Kainé becomes thawed, again, and you pursue the Shadowlord in his castle, again, by assembling the pieces of this key, again. Only this time, along the B route, an additional undercurrent of context is assembled. Suddenly, you, the player, can understand what the Shades — who were believed to be mute goblins — are saying, and their words are both horrifying and soul-crushing.

NieR: Replicant understands context and interpersonal relationships better than most RPGs. It defies narrative expectation and by doing so crafts a story that feels dreamlike in its varied déjà vu, the second play-through affording new angles to what happened the first time around. Nier, justifiably angry over the loss of his sister and the slow erosion of the world due to the increasing violence of the Shades, has foregone his childlike persona and taken on the mantle of a brutal killer. Nier is xenophobic in his rage, undeterred from the war he wages against the Shades and any that might harbor them. Even in moments of sheer brutality — such as when Emil eradicates an entire town or when the wolves are mercilessly slaughtered alongside their Shade leader — Nier is undeterred and unbothered by the bloodshed. He’s become a weapon of singular intent, a sword that will carve his way through any path on the journey to save his beloved sister, Yonah.

The context of the B route goes far beyond additional scenes or added content. Upon reading through a mountainous scrawl of text exploring Kainé’s horrific childhood, we are granted the gift of hearing from her possessor, Tyrann. The Shades, who we learned upon Ending A are much more than violent monsters, suddenly have voices. Every scene we ripped through on our original route is given new and heart-wrenching context, and the full focus of Taro Yoko’s vision begins to spill through the corrosive edges of the narrative: violence is a disease, and it is one that cannot be cured.

Route B might be one of the most compelling narrative sequences crafted in any RPG. Building upon what we thought we knew by providing extraneous context — much of it through new dialogue that is only employed when we are already entangled in a fight — the other side of the coin is shown. There is always another side to the story, and though Kainé understands what is happening in the context of our brutal violence, she does nothing to stop Nier’s rampage. She understands the rage he feels because she has felt it too, but also because in some regard Kainé understands the inevitability of an ever-changing world. The Replicant and Gestalt projects don’t matter, if they ever did. Ripping the wheel from the hands of those that are actually experiencing a living history only to save the bitter souls trapped in the past serves no one. Locked in a steady momentum of repetition, the NieR: Replicant aims to make us understand that layers of context can only add to our understanding of a moment in time; it cannot change it.

A Cycle of Misery, and the Possibility of Hope

While NieR: Replicant may be tedious for some, the way it handles its narrative is done purposefully. By time the player is firmly approaching Endings C/D, they are moving with a terrifying earnestness, striking down Shades with endless bloody abandon in a rush to finally see the apex of the story. They move through waves of discarded humans, punishing souls to the end only for their own selfish regard, certain that perhaps there might be some reward in these final endings that make all of this worthwhile. NieR: Replicant is honest from its harrowed beginning, and although it makes plain that there is no happiness to be found here, it is impossible to defy the human penchant for optimism and hope. Maybe, just maybe, this time up the Shadowlord’s castle will be different. Maybe things will turn out okay.

At the core of the narrative experience is of course the breathtaking masterwork compositions of Keiichi Okabe, whose brilliant and melancholy pieces are so interwoven into the greater identity of NieR that without them would be to unstitch the game itself. Not only are tracks such as Grandma, Kainé/Salvation and Emil/Sacrifice central identifiers of NieR: Replicant’s core emotional being, but the Song of the Ancients is sung by characters in game and reference other meta-narrative notes such as Grimoire Weiss and Grimoire Noir. Every key moment in NieR is underscored by the weighty score, and the heartache delivered by any given seminal moment lives in the mind of the player, inextricably attached to each piece of music.

What has longtime cemented NieR as a work of experimental narrative has been the outcome of its Ending D, which asks for sacrifice not just of the protagonist but of the player themselves, resulting in the complete erasure of their save file. NieR: Replicant keeps this intact, and again the player must watch as line by line, page by page their hard work is wiped from existence in exchange for the game’s true, final ending. NieR does not shy away from the brutalities of an existence forged by violence, and its self-reflection in the final silent credits roll seems penance for everything that the player has wrought throughout the game. Humanity itself might go extinct because of the selfish (but understandable) actions of Nier and his pursuit of his sister Yonah, but what NieR: Replicant does is amend our decade of expectation with one final, truer ending: Ending E.

After the file is erased, it is possible to start the game again. Upon pressing New Game and being prompted to name our character, it’s distressing to find that we are unable to name the file after our previous character (in mine, I was unable to name my character Nier, and so elected for NieR in the new file). The game plays as normal, seemingly, up until the second time at the Aerie where Kainé helps Nier fight the massive Shade that killed her grandmother. As Nier reaches Kainé — who has fallen unconscious after the fight — she hears him through the fall of her blue consciousness and reaches out. Instead of gripping his hand and allowing herself to be pulled back to the land of the living, NieR: Replicant pulls yet another bait-and-switch on us. Nier’s hand dissolves into unusable data, and Kainé is doomed to a breach of unconsciousness, the truth of her reality where Nier never existed, his being still erased by the corrupt system that watches over them all.

What follows in Ending E is such a spectacular addition to the original game that I was giddy to press through it, damned to not crawl into bed until the early hours of morning. Kainé, plagued by dreams of a boy she does not know, finds herself unexpectedly summoned to the Forest of Myth. Studious players who have read Grimoir Nier might be filled with a sudden adrenaline rush of expectation and joy — this is the game’s true ending, and in NieR: Replicant it is appropriately stylized to meet with the series’ future by including incredible calls toward NieR: Automata. It’s an emotional packet of content that is brand new for the series and finishes on a note of surprising optimism — that is, unless, you’re again a fan who knows how things ultimately turn out for Nier, Kainé, and Emil. Regardless, the game again upends expectation by not only providing us with a beautiful new ending, but ultimately restoring the deleted save file, which is another nod that perhaps NieR as a series is not the sad, dark playground that Taro Yoko wants us to believe it is.

NieR: Replicant is a harrowing, emotional experience, one that can now be more widely enjoyed by a fresh audience. Its exploration of themes go far beyond any linear narrative, and instead explore the possibility of audience manipulation via genre-warping segments and possibly the tightest unification of gameplay and soundtrack to ever exist in-game. While aspects of the game might become exhausting for some players, NieR: Replicant deserves all its praise if only because it pushes the boundaries of what to expect from your traditional RPG (or SquareEnix) entry.

Taro Yoko and his team continue to defy expectation at the same time that they draw tears from the eyes of players with the exacting force of wringing out a soaked dishtowel. For fans new and old, NieR: Replicant and its bombastic exploration of narratives both nonlinear and meta craft a truly experimental experience that cannot be missed, and it is a game that will sit at the height of creative discourse and design for years to come.