NationStates and the Age of Browser-Based Games

What will you make of your NationState?

The early 2000s were a landmark era for online gaming.

On its face, this isn't exactly a bold statement. Most people will be able to name some internet-based innovations from this era. It was, after all, the high water mark for MMORPGs, when World of Warcraft dominated the scene. It was the age when Xbox Live brought user-friendly netplay to the console world, blurring the lines between console and PC. Matchmaking services such as Blizzard's Battle.net grew to record sizes, while digital distribution platforms such as Steam revolutionized how video games reached consumers.

Yet it was also an age of smaller changes that were just as profound, even if they fell beneath the notice of the gaming press of the time. In this same period, Adobe Flash really took off, with Flash games becoming more sophisticated and more practical to monetize. It was an era of browser-based games, encompassing everything from tick-based strategy games to minimalistic MMOs - some of which have endured to this day. It was, in short, the start of the democratization of video games - though none of us thought in those terms at the time.

About once a month, one of my friends would come to class having discovered some wonderful new game that we were all obligated to play. But there was one that I found all on my own, probably because it appealed to my teenage self-importance: Max Barry's NationStates, a geopolitical simulator.

No one was more shocked than me to learn that NationStates is still going strong. I managed to miss the 20th anniversary of a game that, by all rights, should have lasted a year or two at most.

So what does it take to keep a simple game going for 21 years? The short answer: A loyal community.

Some people might quibble with my calling NationStates a "game." In modern parlance, we might call it a "sandbox" - an interactive experience with no specific fixed goal or defined win-states or lose-states.

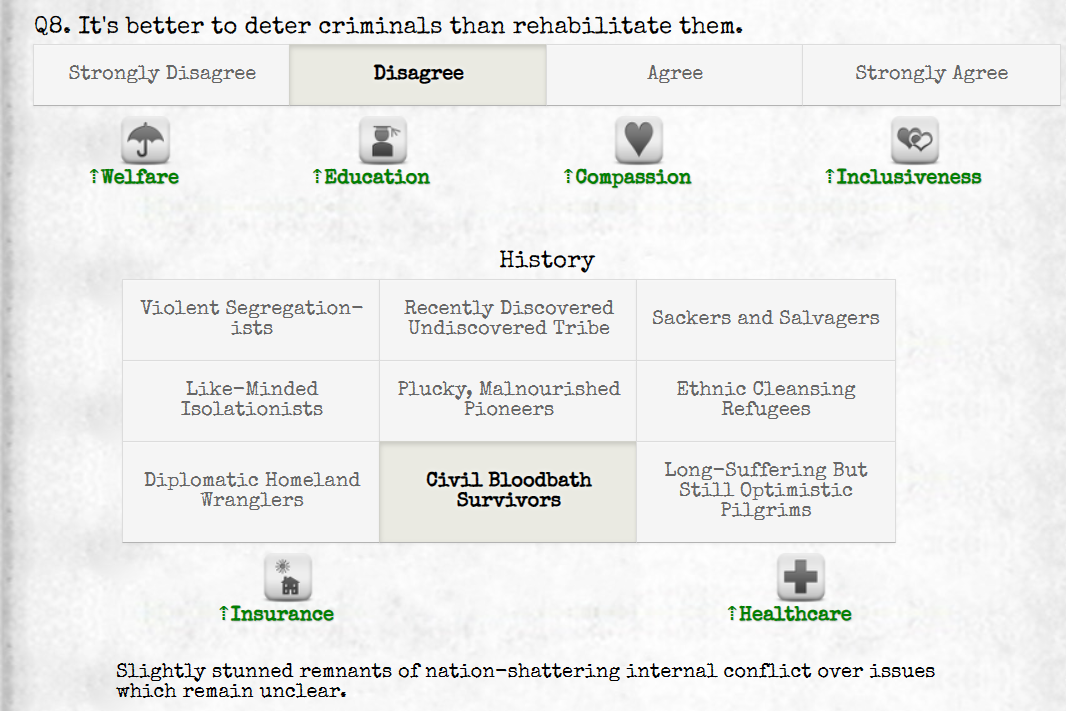

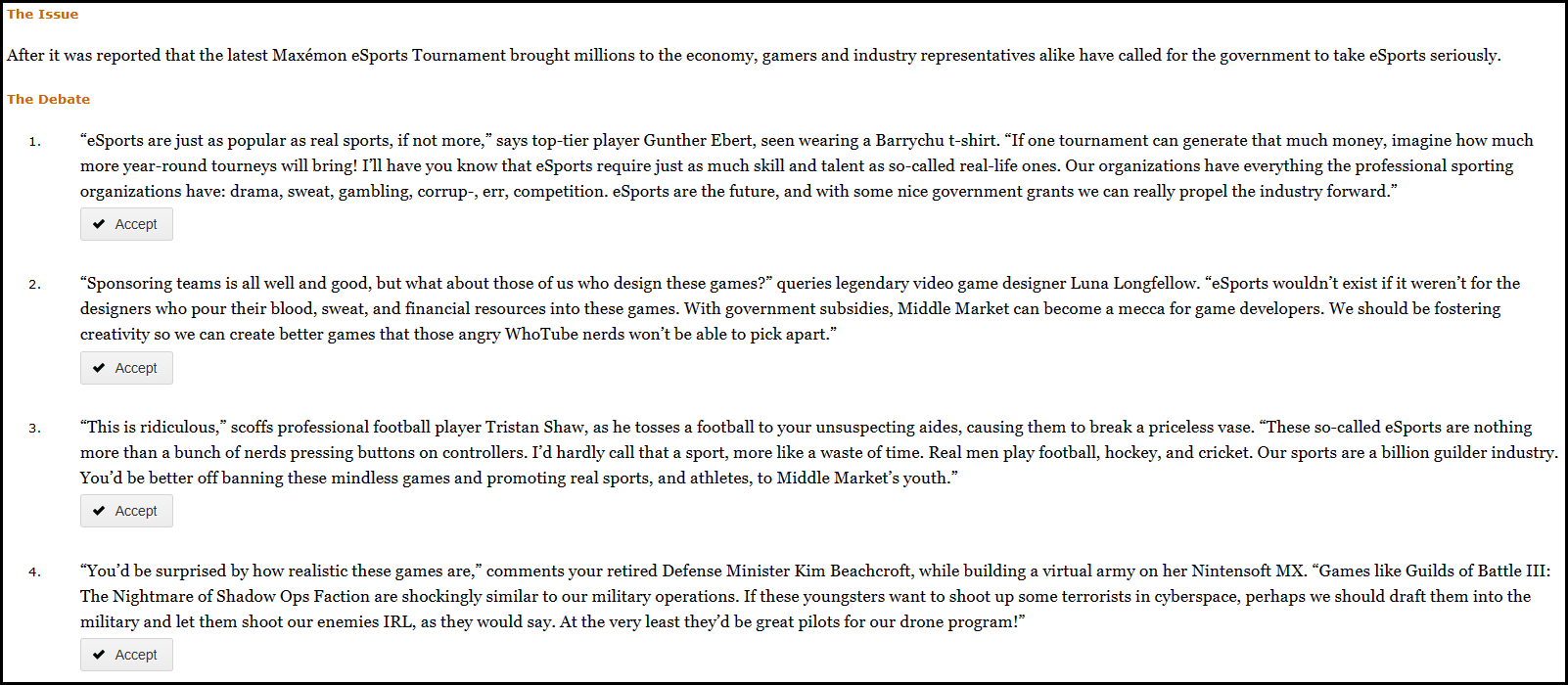

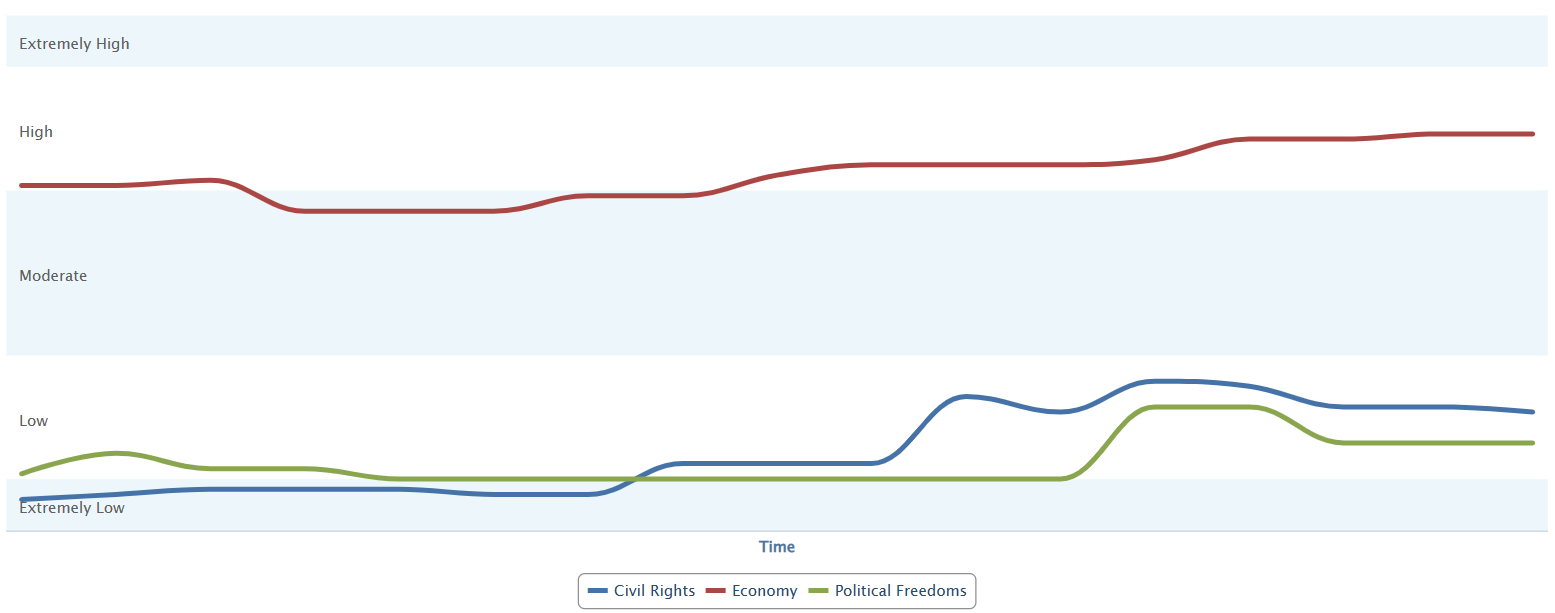

The player is given control of a new country in an alternate Earth, with the government type defined on a three-axis scale (personal, economic, and political liberty). After taking a brief survey to decide the initial state of the country, the player guides its destiny by making decisions on emergent issues. Most of these issues are based on real-world controversies but with the decisions skewed in an absurd and humorous direction, often with at least one option that no real-world government would entertain (hopefully).

Based on the choices the player makes, the nation's politics will shift across the three axes. You may start off as an Inoffensive Centrist Democracy and grow into something more colorful - perhaps a Compulsory Consumerist State, Iron Fist Socialists, or Tyranny by Majority.

That's about it. It's an extremely simple game, one that's accessible to pretty much anyone who can operate an internet-capable device and possesses basic reading comprehension.

Stepping back into NationStates after two decades has been a fascinating experience, both for how it's changed and how it hasn't.

Fundamentally, nothing is different. An issue comes up (some are even holdovers from the original iteration), you either make a decision or dismiss it, and the game adjusts your stats and adds a new phrase to your description to reflect the unintended consequences. The issues arrive more frequently - they come at timed intervals rather than once per day, and you can have more than one at once - but that's about it.

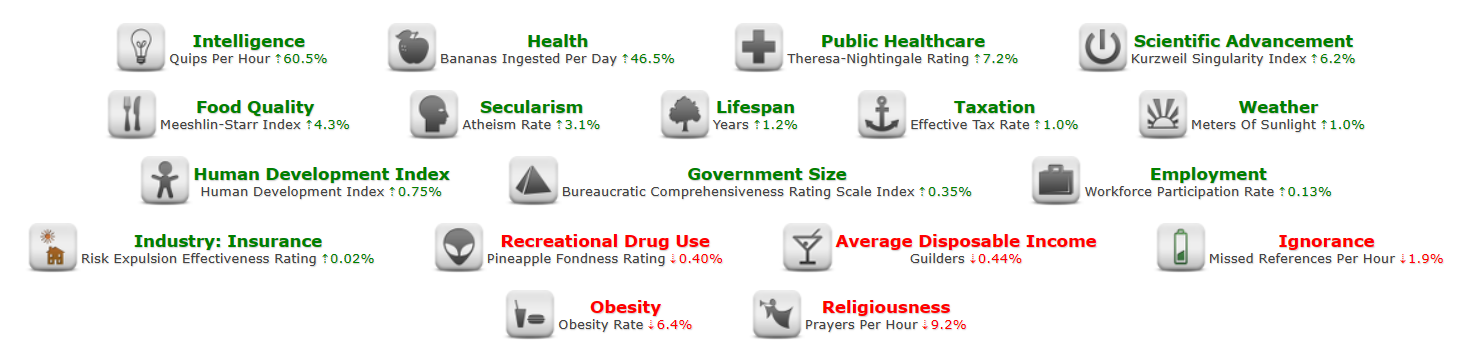

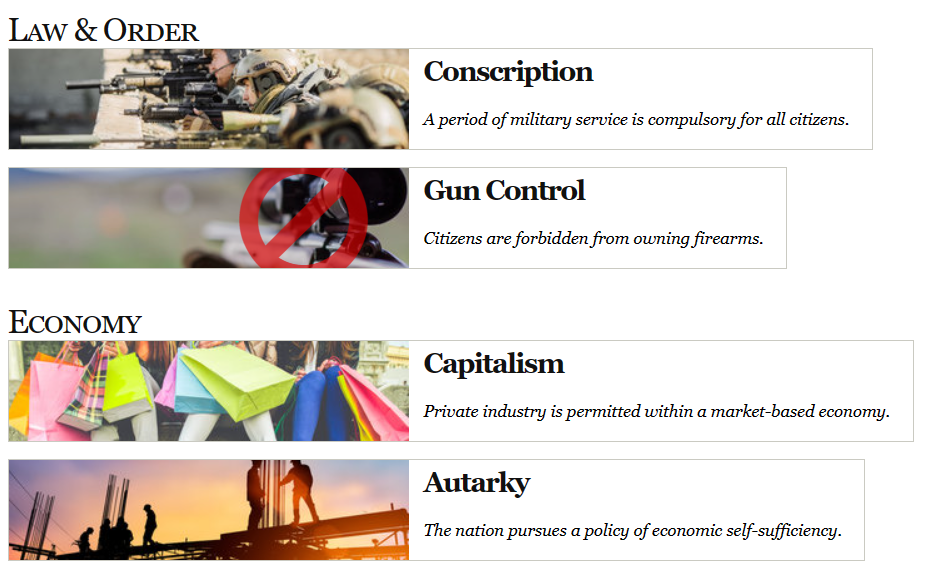

In other aspects, the game looks radically different. The interface now provides far more information to the player - data on economic sectors, government spending, and various and sundry metrics on the lives of your citizens. There's even a user-editable factbook section that allows players to create a custom history and culture, all separate from the description generated by the game itself.

Absolutely none of the information is mechanically useful. It exists solely for immersion purposes - to enhance the role-playing experience. Even though it doesn't look like it, NationStates is a role-playing game at heart.

NationStates was a product of an era in which people still created websites solely as a means of self-expression. But this game was originally created for a more specific purpose: It was made to promote a novel.

There's a history of using games - either electronic or conventional - to promote other forms of media, with most of that history stemming from the growth of the Internet starting in the 1990s. Simple online games and digital toys have been a fixture on websites for films, TV shows, and even music albums for decades. Literature, on the other hand, has been mostly left out. The publishing industry remains very stodgy in this regard, and aside from a few hypertext stories, there hasn't been a lot of innovation in the promotion of works of fiction.

Enter science fiction author Max Barry. NationStates initially existed primarily to promote his 2003 novel Jennifer Government. It worked, too, because I owned a copy of Jennifer Government, and it was mostly due to NationStates.

Jennifer Government is an alternative dystopian novel set in a system defined by extreme libertarian politics. It's a neo-feudal world in which people are named for the companies that employ them, corporations engage in literal shooting wars and safety is only for those who can afford it. The story begins with two executives from a sneaker company staging a mass murder as a form of marketing (danger sells, after all) and follows various people with varying motivations as they try to get to the bottom of what happened.

What's interesting is that there's actually very little that connects the novel Jennifer Government to the game NationStates, apart from both of them dealing with fringe politics of the not-so-distant future. If you really want, you can recreate Jennifer Government's anarcho-capitalist hellscape in NationStates, but that's just one possible outcome of many. Players are free to create their own utopian societies or roleplay any real-world or fictional government they choose.

This is one key distinction between NationStates and many other failed attempts to use video games as promotional tools. NationStates was first and foremost designed to be entertaining. You could play the game for years if you wanted and never feel left out because you hadn't read the book. As a result, this little promotional game has enjoyed a life that has continued long after the novel has faded from view.

But the real saving grace for NationStates has been the player base. Online games thrive for as long as there are people who care about them, and there are at least 290,000 people who care about this one.

The forums really tell the tale of NationStates and its inexplicable endurance. The game has spawned a massive roleplaying community that far exceeds the simple mechanics. Players discuss fictional issues in the personae of the leaders of their fictional countries, engaging in diplomacy and warfare despite there being no in-game rules for either one.

Titles like this offer the player a chance to approach the game any way they choose. You can play it casually, checking in on your issues over your morning coffee and otherwise giving it no thought. You can also go in-depth, playing it like a simulationist RPG and getting lost in the affairs of your own little slice of a virtual world.

I created a fresh account for the purposes of writing this article, shaping my country into a version of a fictional state from one of my own works - a nation of trade companies organized beneath an authoritarian ruler who keeps order through common culture and moralism. My goal was to slowly liberalize the nation while still maintaining my absolute, unquestioned grip on power, and to accomplish this while not violating my nation's mores.

Even after I'd mostly finished the article, I kept on playing NationStates, shaping this virtual state using the simple tools at my disposal. Get yourself into a game like this, and it's more engrossing than you might expect. More than anything, though, it made me miss an age when the internet was a space for unrestrained creativity for its own sake, rather than for commercial gain.

But if people are still interested in NationStates, then there's still hope.