My Work Is Not Yet Done Puts the Anxiety in ‘Anxiety Horror’

Discussing 1-bit theological horror with lead developer Spencer Yan and composer Sam Tudor

Does the Pope poop in the woods? Well, I don't have an answer to that and neither do you because it's a rhetorical question. The only people who might hold the answer to that are Pope Francis himself, Star Trek's Q and possibly that bearded wise guy with millions of CRT monitors from The Matrix. If you're wondering what all this has to do with interactive entertainment that we, the gamers, love and enjoy with lip-smacking enthusiasm, please roll with me for a moment.

At the cusp of his twenties, Spencer Yan went to Delaware Water Gap, a 70,000-acre national park that's part of the Appalachian Trail. He doesn't remember exactly why he went there or what was the trip's purpose. He does, however, remember the creamy milkshake he got at dinner that same morning, one that would soon enough start messing with Spencer's stomach. By the time his gastrointestinal tract started acting up as if it was Woodstock '99, Spencer was already neck-deep in the woods, surrounded only by leaves, mud, and his own shadow. The nasty urge "came about in a really inconveniently desperate way" and he decided to surrender to his aching colon. Dropping trou in nature was not a new or novel sensation to him by any means - we are all but humans after all.

However, this time was different: squatting there, alone and pantsless, Spencer was hit by a revelation. "The absurdity of it all became starkly apparent to me in a way I had not really recognised before," Yan explained to me. "At the risk of sounding like a ridiculously pretentious asshat, [this experience] singularly changed my metaphysics in a way that no amount of scholastic eloquence or rigour could ever hope to effect."

Most of us would hope to come out of such an uncomfortable situation with minimally burning behinds, or, you know, no stomach cramps waiting to jump you when you least expect it. Instead, what Yan came out with that day resembled an idea that came to form the basis for his 1-bit narrative-horror game, My Work Is Not Yet Done.

There was also a terrifyingly sublime epiphany that Spencer experienced several years prior while chatting with a friend on the beach. It "was not some great Pentecostal miracle of awakening," Yan explained to me in a post-interview email; rather more like watching a movie you've seen a dozen times with no memorable effect on you, until one day "it hits you deeply, in a way you cannot fathom."

In any case, this unfathomable sense of aloneness in the world that Yan experienced made him pick up a Bible that very same night. He wasn't particularly religious at the time. But "for whatever reason God all of a sudden no longer seemed so remote of a concept to contemplate," Yan told Rock Paper Shotgun's Edwin Evans-Thirlwell years later. This newfound interest in religion and specifically theology soon came to shape My Work Is Not Yet Done in ways you will understand by reading the following interview.

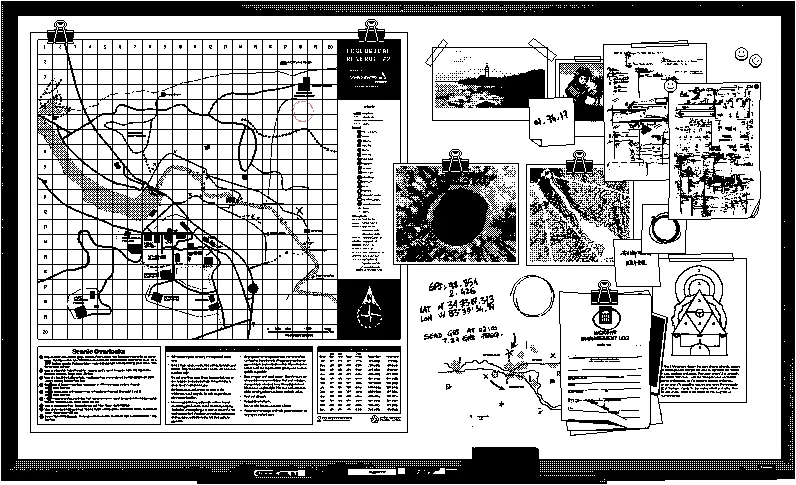

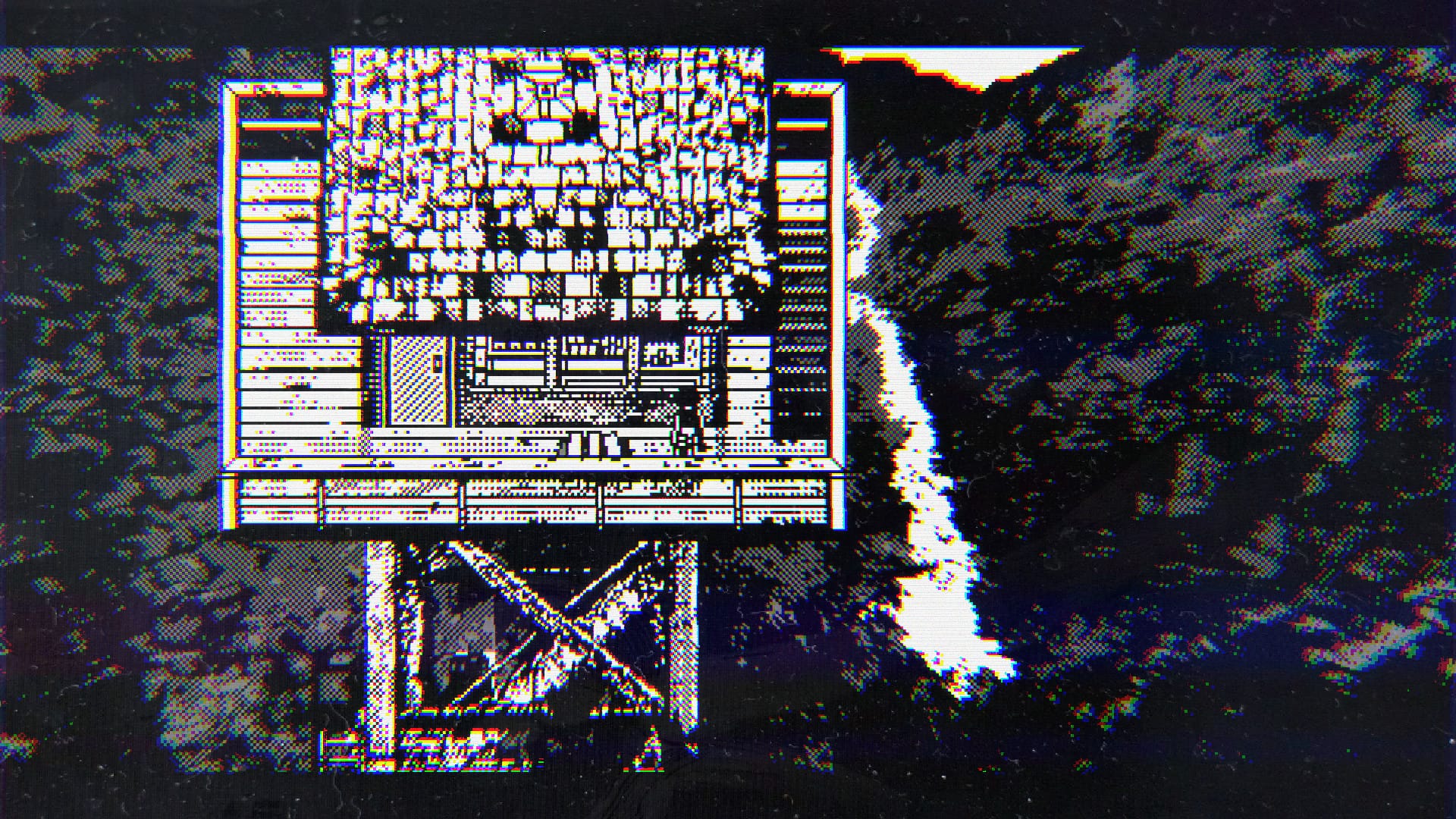

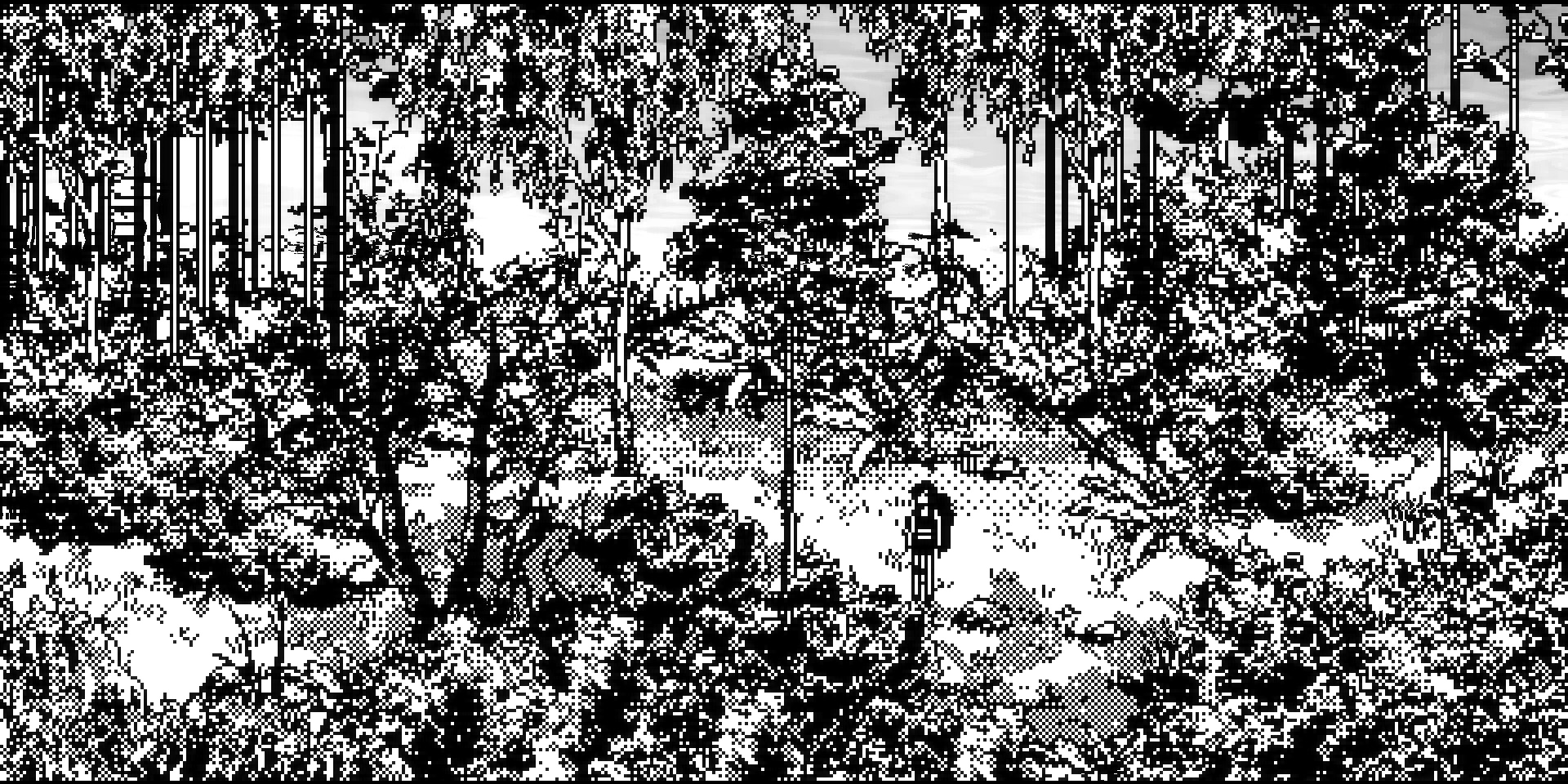

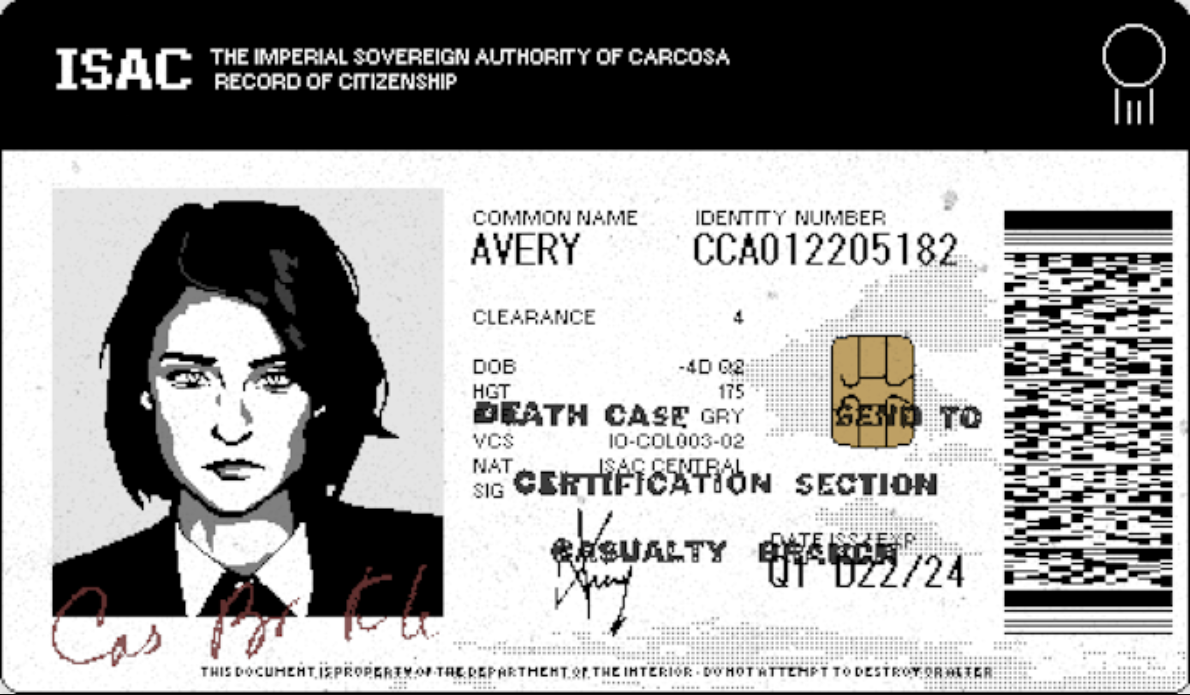

So what is My Work Is Not Yet Done, exactly? Well, for starters, it's a monochromatic 1-bit narrative-driven horror game, or a "pilgrimage simulator" according to its Kickstarter page. Players control Avery, the last surviving member of a group of scientists that was sent to eerie, highly isolated woods to retrieve an enigmatic signal. If that sounds a bit like Jeff VanderMeer's hallucinatory Annihilation mixed with a perfect amount of Firewatch's unintentionally terrifying atmosphere of being alone in the bush, you're not wrong. Yan claims he was introduced to Annihilation - both the book and its screen adaptation which he thought was just "okay" - when the game was already a good way into development.

There's also the pace and everyday idiosyncrasies that, for better or worse, will be familiar to everyone who played Hideo Kojima's Death Stranding. You will have to replace batteries in the sensors ("Every single battery in the game has its own individual charge. They all depreciate at somewhat similar rates and various things can affect the rate at which batteries depreciate"). Take a shower and use the toilet. Like most things in the game, there's an incredibly detailed worm farm that you can operate and use as a source of nutrients like its the year 2049. Again, sort of like Death Stranding but with less action involving chucking piss at paranormal entities.

When I reached out to Spencer for this interview at the start of February, My Work Is Not Yet Done had a snack-sized demo available and the pretty old news that Raw Fury had picked it up for publishing duties. Not much else in the update department, except for the fact that Spencer was set to be joined by the composer Sam Tudor. A taster for what he's cooking up for My Work Is Not Yet Done can be heard in the game's latest trailer.

Source: YouTube.

While I didn't come into our interview expecting any big announcements from Spencer, our conversation started with the news of him parting ways with Raw Fury - for reasons he explains in his recent Kickstarter update and the following interview. He then went on to reveal that no work has been done on My Work Is Not Yet Done since the release of his demo. And that he's training to become a priest... again! If there's a better way to kick off a conversation about a game developed by a would-be priest and inspired by a horrible pooping-in-the-woods experience, I've yet to hear it.

I hope, then, that what you'll read next will inspire you to try out My Work Is Not Yet Done and perhaps do some fun research into the wacky, little-known horrors of the Old Testament. Spencer's game might not see the light of the day for the foreseeable future, but at least we can talk about it. Based on how much fun one can have talking about the game or its influences (also see: Warren Spencer's 'One City Block' game, Baldur's Gate 3, Metal Gear Solid 3), it's safe to say that Spencer and Sam are onto something special here. Whether we will be eating, well, not worms by the time it comes out, that's uncertain.

SUPERJUMP: Have you ever played Cart Life? This kind of old, realistically difficult, grim indie game. While playing My Work Is Not Yet Done, I got the feeling of this and also Heavy Rain.

Spencer Yan (lead developer): That's interesting - those are two games I've never thought would be compared to mine. Now you've mentioned it, that’s a very interesting set of comparisons.

But yes, I actually have played it. A very long time ago. Maybe in 2017.

SUPERJUMP: What I found really fascinating is the pitch document you published on Medium. This was the first time I read anything like that. What inspired you to do that?

Spencer Yan: I'll start with the first part, which is my introduction. I guess game development happened through modding and through some combination of luck and opportunity. I happened to be one of the first people who publicly tried to mod Hotline Miami. I learned how to mod that, as I learned how to use a computer for coding purposes - I didn't really use computers before that. Everything was brand new to me. There was no documentation about any of it, anywhere. I didn't know what a forum like Reddit was back then! I was discovering all these things like brand new.

Before I signed with Raw Fury, I had never really considered a publisher because I told myself that the kinds of games I wanted to make were just too unconventional, for lack of a better word. So I was just like, ‘Well, no publishers will ever agree to work with me.’ But when they did, I extensively researched how publishers work to begin with. And that's what led me to my conclusion.

During that process, I saw so many posts from other developers wondering about how publishing seemed to be like this huge black box. So I want to open up my process both because I wanted to provide a resource for other developers and also show people that even a game as unconventional as my own - which goes against a lot of things that people say are not good game design - can find a fairly reputable publisher.

"Everything was brand new to me. There was no documentation about any of it, anywhere. I didn't know what a forum like Reddit was back then! I was discovering all these things like brand new."

Spencer Yan

SUPERJUMP: When Raw Fury offered to publish your game, why did you agree? In your blog, you said you have a tendency to sabotage your projects. Did agreeing to have a publisher mean that you would have to stick with the schedule and all of that?

Spencer Yan: A big part of it was the fact that they had had a history of being more open to things that are considered unorthodox within publishing work. They had a history of publishing kind of unconventional games.

Around that time they published a game called Norco which was a very successful project by all means, for what it was. That meant that [Raw Fury] could handle sort of the philosophical aspirations of the project.

I made it very clear to them that this is a balanced relationship - this is this is not me working for you. This is us working together towards the completion of this thing. And they seemed very happy about that, too.

SUPERJUMP: So what went wrong? When and why did you part ways?

Spencer Yan: Well, we‘ve been separated for almost a year now, at least spiritually. It was a mutual decision.

It just happened to coincide with a bunch of stuff in my private life. I'm 26 and a lot of things were just happening, on top of working, which just tends to happen around this age. I never expected them to help me deal with my personal issues. But I did want their understanding and they were very understanding of it.

I think the biggest factor that contributed to my decision to separate from them was that I just didn't feel like they were helping me in the ways I wanted them to help. Which was basically: A) Provide me a structure for the game, which they kind of did. And B) Get me in contact with people to talk with.

I think it's been four or five years at that point that I've been working alone. It kind of really got to me in a way where I just did not know whether the stuff I was doing [meant] anything; or whether [Raw Fury] really cared about the game.

It's really the fact that they didn't get me any interviews - all the public sort of processes about the game I've had to go and either get myself or people like yourself reached out to me. None of that happened thanks to Raw Fury. That was a big point of frustration for me because I figured Raw Fury is a well-known name in the industry, they should be able to get me in contact with writers or even just other developers who might be interested - if not writing about My Work Is Not Yet Done publicly, at least discussing its ideas. But it never did.

If someone asked me, ‘Would you recommend someone to work with Raw Fury?’ I would absolutely say yes. In a lot of ways, they were unusually kind of understanding, and accommodating to me. But at the end of the day, there's still a corporate structure that abides by a corporate standard where not everybody on a project is fully invested in. Which I think is what I kind of naively went in expecting.

SUPERJUMP: What does that mean in terms of the game‘s release date?

Spencer Yan: I'm going to be honest - I haven't really worked on the project since releasing the demo. I just wasn't sure what to do because [Raw Fury] wasn‘t telling me what to do with it. I just wasn't clear about where to take the project. My [initial] goal with the demo was to establish how the public views the project at this point. And how do I move forward from there. I don't feel they really helped me to clarify some things. That clarity didn't come to me for a while.

Right now, I'm in the process of negotiating the spirit of the project. My life has changed since I started this project when I was 21. Now that‘s a long period of time. Physiologically, neurologically - my telomeres are about to start decaying. [laughs] I changed but the project hasn't. But since I've changed, that means I have to continuously practice this renegotiation of its value to me. It's something that I'm happy to do. But I needed to take a bunch of time away. And I don't think I fully appreciated the need for that until very recently.

SUPERJUMP: When you open up the demo, there are four different titles on the opening screen. Does that mean My Work Is Not Yet Done is just the first chapter of the saga?

Spencer Yan: My Work Is Not Yet Done takes place in this kind of larger world that I kind of really want to pursue. I see My Work Is Not Yet Done as both kind of a prelude to everything that happens in this greater internal mythos, and the end of it. This is something that I hope the game will be able to explain in less cryptic terms.

SUPERJUMP: So if this is the first chapter and it took you four years to make, how long do you think it will take you to finish all chapters?

Spencer Yan: That's a really difficult question. [laughs] Upon reflection and the active process of still working on it, I think that a large part of this game's development was not really spent on My Work Is Not Yet Done development, but on personal development. This is not something that I'm particularly ashamed of admitting. I'd maybe work four days [per week] maximum and the rest of it is just me dealing with personal issues.

I started this project at the end of 2019. That means it's been five years already. But two or three-quarters of those years were spent kind of just not working on the project directly. It was either dealing with other things or trying to figure out how to live in a better way, trying to figure out what to do about my life situation. And I count that as development time. Technically, it‘s not time spent developing the game. But when people talk about the writing of novels or whatever, the author wasn't literally sitting there writing the book for 10 years (hopefully).

This is one of the things that I really want to emphasize with my active development logs. When creatives talk about the act of creation, or the process of creation, they focus primarily on the technical aspects. But I think it's something that goes unsaid, just how much time is taken within that process to the act of living. If someone starts making a game at the age of 18 and doesn't finish it until they're 27 - what happened in those nine years? That's the fundamental appeal of films like Indie Game the Movie. They're not films about making games, but [rather] stories about people making games.

SUPERJUMP: Are the rest of the chapters going to be made in the same style?

Spencer Yan: Something that I want to pursue with all my projects is that I want each project to represent a different aspect of this universe.

I remember there's this one quote my friend told me while we were watching some weird horror movie; he turns to me and says, ‘You know, if you really think about it, Mamma Mia and Saw take place with the same shared cinematic universe.’ For some reason, that, of all things, stuck with me.

So for my other projects, I kind of want to diversify the mood. There is sort of this shared sensibility that just comes naturally from the fact that I'm just one person and I don't think I'm a very good fiction writer - I have a pretty poor imagination when it comes to imagining the lives of others, imagining lived experiences that exist outside of my own.

My Work Is Not Yet Done tells the story of this specialized scientist effectively working in a highly isolated environment which kind of doesn’t exist. The next project that I would like to work on after this one is almost the complete opposite of My Work Is Not Yet Done. It would notionally be about these university students in a sort of slice-of-life game with none of this cosmic horror stuff, none of this philosophical horror stuff. Just people living their lives. Tonally, it will be very different. But I'm probably not going to add colours to my games any time soon.

SUPERJUMP: Isn’t it depressing, for lack of a better word, to work purely in black and white 1-bit dimensions for so long?

Spencer Yan: I never thought about it that way. But I don't think so. When I was younger, I wanted to be a landscape painter. And I found that when you’re working with watercolours and acrylics, you have to blend your colours perfectly on the spot, which is a skill most people do not acquire unless they've spent years doing these things. At the age of 13, I did not have years of experience doing this. And I did not have the patience to develop years of experience for learning this. So I kind of developed a distrust and suspicion toward colours in my work very early on.

I think that mindset carried over. There's a kind of utilitarian efficiency and clarity to not using colours that speaks to me. I personally find the challenges of working in black and white more interesting than learning how to properly work with colours.

"My Work Is Not Yet Done tells the story of this specialized scientist effectively working in a highly isolated environment which kind of doesn’t exist. The next project that I would like to work on after this one is almost the complete opposite of My Work Is Not Yet Done."

Spencer Yan

SUPERJUMP: Is that why you chose to make the game in 1-bit?

Spencer Yan: I get a lot of people asking me if the game was meant to be like to look like an old game. Truth be told, it was not meant at all to look like an old game.

I have very little nostalgia [for retro games] because I never really used computers until I was fairly older than the period in which you develop sentimental attachments to things [like that]. So for me, it was primarily a pragmatic and stylistic choice. I wanted a visual style that would be very quick to work in - a visual style that would allow me to communicate things very quickly and very kind of efficiently.

When you add colour to the mix, it compromises both of those things. For example, in the opening of my game, there's a sunset and people don't know if it’s a sunset or a sunrise. It's the black and white that makes it ambiguous. And you really can't really get that with colours.

SUPERJUMP: Besides the atmosphere, which I would describe as chilling in a similar way to Jonathan Glazer's Under The Skin, it's pretty difficult to pinpoint exactly what makes this a 'cosmic horror' game

Spencer Yan: Honestly, I kind of reject the 'cosmic horror' label. I think early on the way I used to define My Work Is Not Yet Done was a 'survival game with horror elements'. I don't really think about it as a survival game anymore. I think my current branding reflects the most accurate label for it which is 'an investigative horror game'.

To be honest, I'm not as focused on the horror aspect as others seem to be. For me, the atmosphere of horror is secondary to the thematic elements of My Work Is Not Yet Done.

For the longest time, I felt kind of pressure to make the work scary, I guess. I was coming up with all these random things that happened in the world - encounters and stuff like that. At a certain point, I was like, ‘Wait, why is this stuff in here?’ Am I including this because somebody on Twitter thought that it would be cool if this happened? I don't care about that stuff - that was never part of the plan. So there was a big process of re-evaluation.

One of the things I really wanted to determine with the demo actually was how little or how much that [horror] label actually mattered. There's nothing in the demo that’s overtly horrifying or genuinely scary.

I think the term that I would use to describe my work is 'oppressing confusion' - a pressing sort of destabilization and uncertainty. It’s why I call it an 'investigative horror game' in the first place. Although I wish I could call it an 'anxiety game' but that’s not a real genre.

SUPERJUMP: Well, your game could be a genre starter

Spencer Yan: That stuff is for people who make a lot more money than me. [laughs] People with a more established reputation. Maybe they can make their genres or whatever, and let us see whether that sticks on.

For me, it's about provoking a certain kind of unease and anxiety that comes from not really being certain of things. There are a lot of little things in game design that are used to destabilize the players’ notion of what is going on, not just in a thematic or narrative sense, but also mechanically.

One of the things I really like to do is put people in front of the demo and watch them spend hours wandering around. If you played the demo, you will know that it’s a super small area – the Outpost is just two blocks down. And usually they get increasingly uncertain about where they're going. You can see them getting frustrated.

A lot of developers might take that as a sign that what they've designed needs to be refined for the player. But for me, that’s generally a good thing. That's the kind of feeling I want to provoke. I want people to come to the game thinking that they know what they're getting into. And then realize that no - you won’t get to play by your own rules. You will have to play by the game's rules. The same way this mirrors the narrative function of the character, which makes her realize that the tools she [believes] she knows how to use don’t really work the way she’s used to them working.

SUPERJUMP: What’s your relationship with horror? Do you have a personal favourite horror game?

Spencer Yan: I have an ambivalent relationship with horror. I find it interesting to think about. But I'm the kind of person who prefers slasher movies to psychological horror and ghost horror. I am not a very cerebral person when it comes to my tastes - all the stuff I like is pretty different from the stuff that I make.

As for my favourite horror game, it's difficult because I don't play them. Well, I do play a lot of horror games but I don't really enjoy them to be honest.

SUPERJUMP: So why play them?

Spencer Yan: To keep up to date. The way I see it, it’s work-related research. If you're an author, you might read everything, right?

There's this game called Welcome to The Game II. I think that's probably my favourite horror game. It's basically about this guy who sits at a computer. When you ask the computer, you can look at all these messed up fictional websites that are extremely uneasy to look at. You basically click around these websites and you try to find hidden links so that you can open other links.

As this is happening, various threats happen in this apartment building around him; you can get up from his computer and look outside your window. You can get swatted, if you spend too much time looking at certain websites, for example. And there's his whole minigame aspect to it where you can buy various botnet trackers and stuff. You have to change your Wi-Fi in-game constantly so that the police don't come get you.

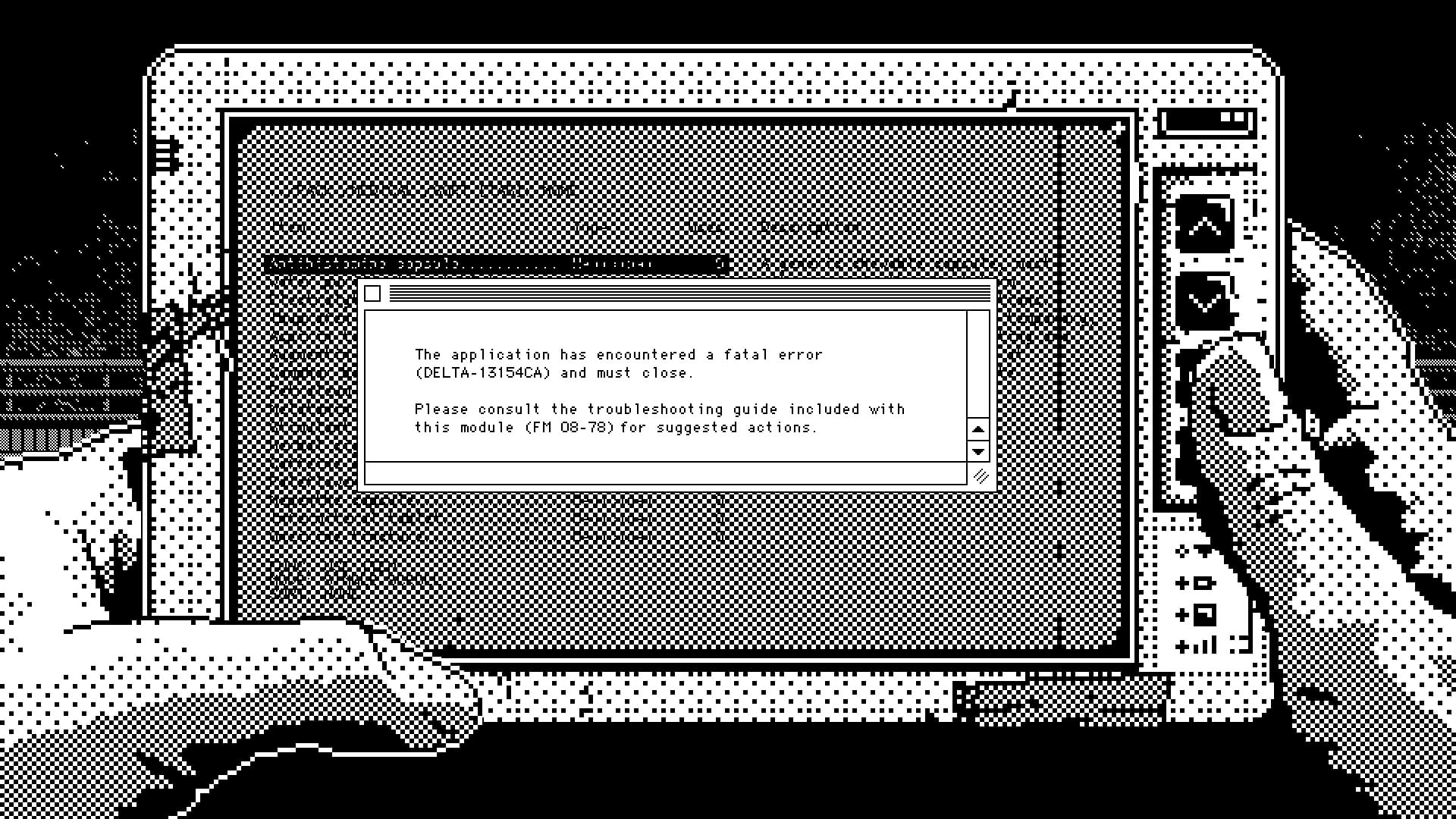

I feel like Welcome to The Game II has been a very strong point of inspiration for my game because it combines the aspect of interacting with an interface. So part of the main gameplay exists within this interface which is separate from the lived world. At the same time, you have to like be very cognizant of what's happening in the embodied existence of the character. You can't just sit there all the time, be clicking around around the web because, oh, someone just stuck into your apartment and stabbed you in the back!

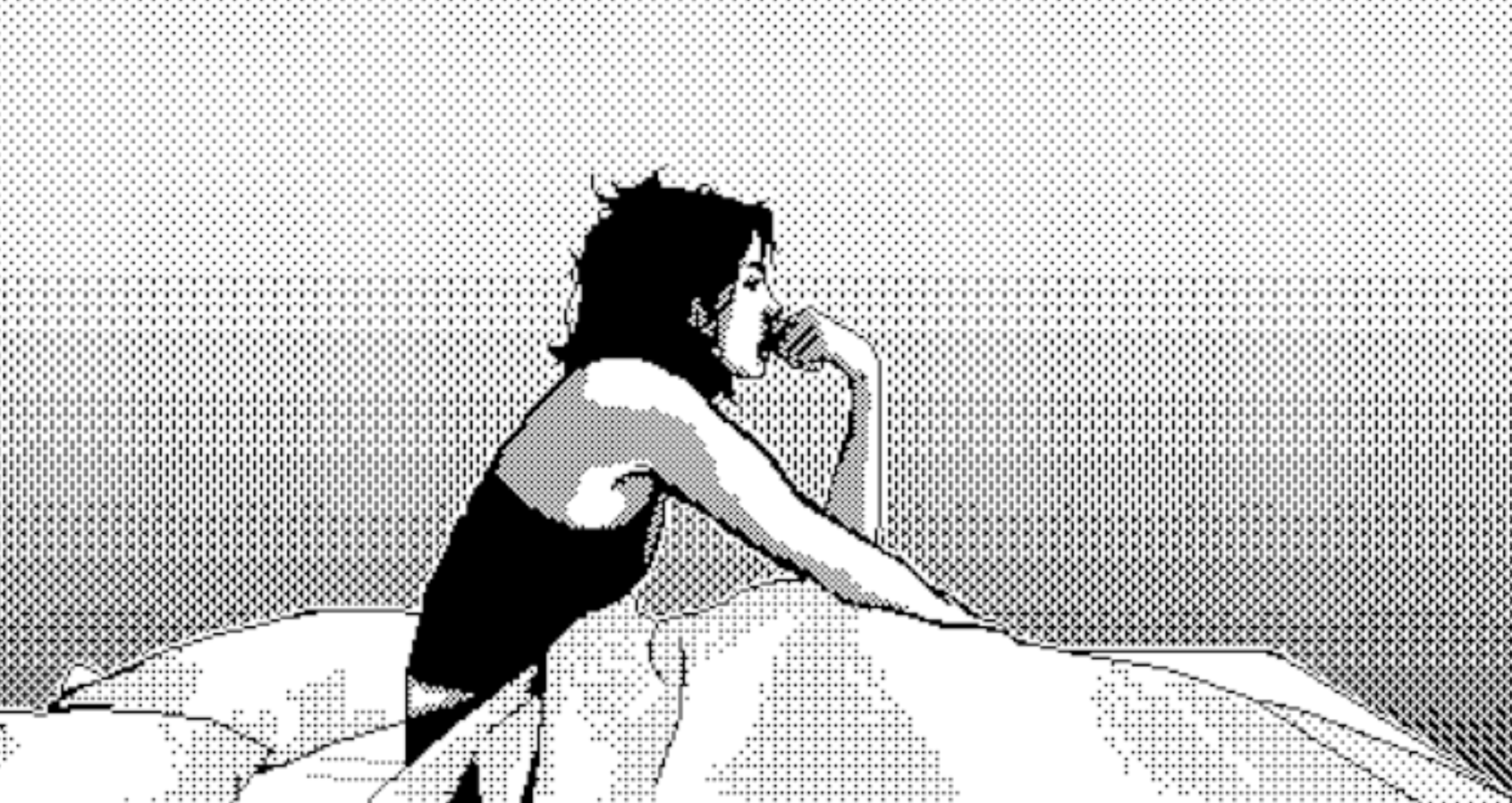

You know, I like the idea of having to balance these two modes of existence. My Work Is Not Yet Done is not so much about an active threat stalking you; instead, you have this much slower kind of creep - a bodily kind of decay. The character’s bodily mechanisms catch up with her.

A big part of the game is about the frustration of scientific research. You're running these processes, these programs and trying to locate these people. At the same time, this character is also a human being - she has to eat, she has to sleep, she has to drink water, she has to shit and piss. And sometimes [machines’] sensors will break down. You know, we're still used to talking about the cloud in these abstract terms. But everything that exists in the cloud or on a network is backed up in a physical thing. There are disks that serve as her server - these systems will also fail as the game progresses. That means that now she has to go and investigate those in order to get back to the main work of trying to basically find the signal. This way there's this greater level of meta-narrative to it where the player is also trying to figure out what has happened to her or why she's even here in the first place.

"You know, I like the idea of having to balance these two modes of existence. My Work Is Not Yet Done is not so much about an active threat stalking you; instead, you have this much slower kind of creep - a bodily kind of decay. The character’s bodily mechanisms catch up with her."

Spencer Yan

SUPERJUMP: Can you explain your reasoning for tracking the character's calorie consumption together with the presence of solids and liquids, among other things?

Spencer Yan: Part of it is because I was developing My Work is Not Yet Done as a survival game. At the time of developing this version, I was also looking at survival mods and survival games to understand why people don't like survival mechanics and games. Because, unlike in real life, when you're hungry or tired, hurt or fatigued, those are things that have noticeable effects in games; it might be a debuff to your health or to the speed at which your character can walk - it's not really meaningful. There are very few games that do try to make it more meaningful. However, by the time it becomes more meaningful, players will think of it as an annoyance.

I think a good survival game is one that is built ground-up as a game about surviving first and foremost rather than about building or whatever happens to have survival mechanics in it.

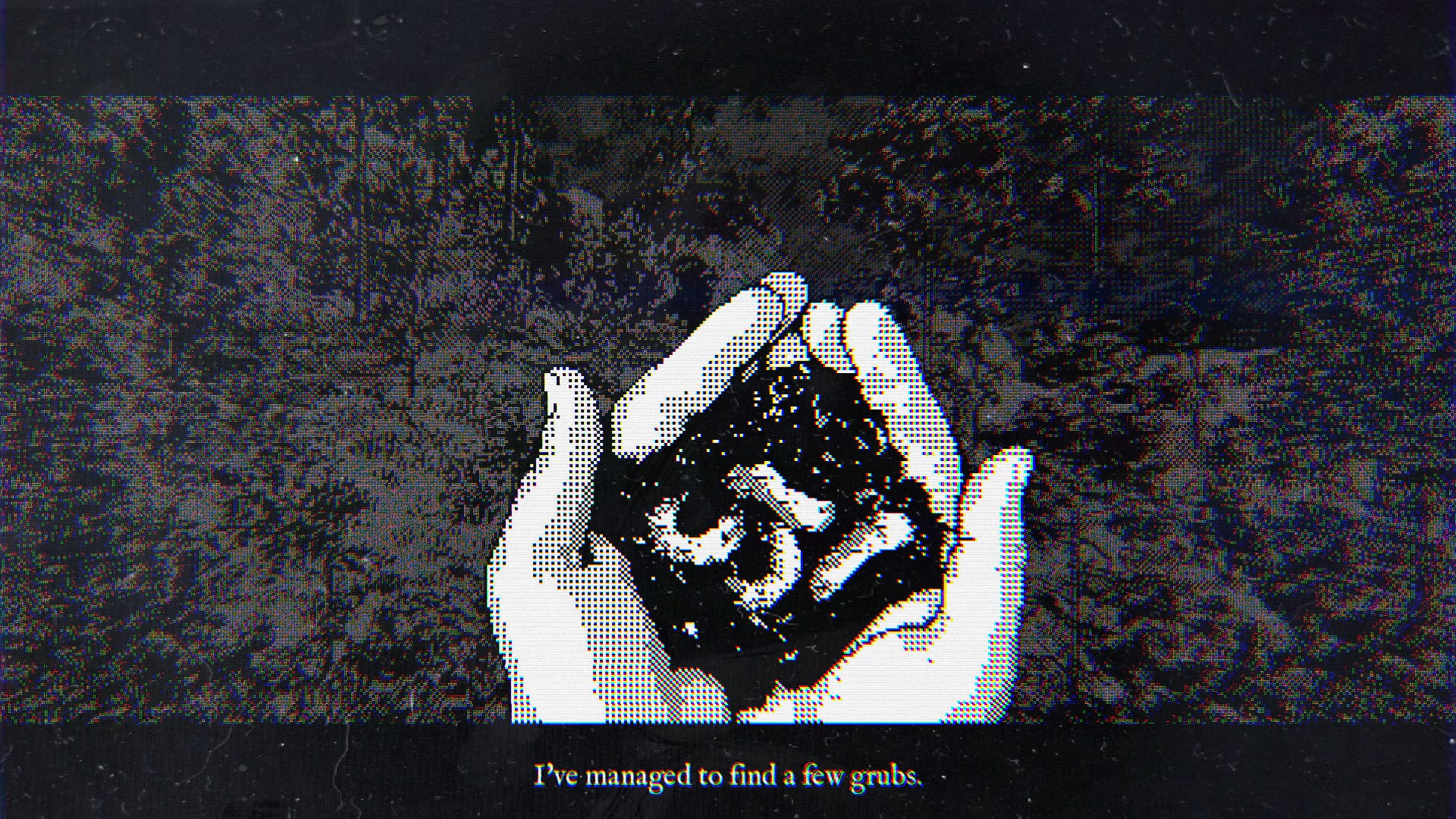

When I started working on My Work is Not Yet Done, I was like, ‘Okay, I'm going to be making a game about how much it sucks to shit in the woods.’ Prior to making it, I had a really bad experience with shitting in the woods. And I realized that being in the woods sucks. Games make it look so nice and beautiful. But actually, it sucks. Then, I started thinking: ‘Well, if I want to make it authentic about how inconveniently painful is to do that, why not think about food and hunger, too?’ Everything comes in and has to come out from somewhere.

I definitely lessened the effects of it severely [in the current version of My Work is Not Yet Done]. Now it's mostly just walking, sitting down and picking things up and putting them down. But I wanted to keep the granularity of those systems because, even if the player never sees them or interacts with them directly, it reinforces the feeling I was telling you about earlier: there are things going on in the background that someone knows but you don't know. And that is constantly shifting.

For example, every single battery in the game has its own individual charge. They all depreciate at somewhat similar rates and various things can affect the rate at which batteries depreciate.

Let's say you're sitting at the computer as this character and a sensor suddenly goes offline. You don't know why it's gone offline but you walk over to the sensor, you've spent a bunch of time trying to look for it because you don't know how to use her locational tool, and you don't know how to read the map. You’ve spent all this time and got lost. All of a sudden, it gets dark. You still haven't located the sensor and the batteries are low. Now you have to figure out what to do: do you set up a fire and sleep outside? Well, she doesn't like to sleep outside because it causes muscle sores. That will ultimately affect her ability to do things later on. And this is even before she gets to the sensor...

All these things interacting at once create this experience of suspicion and friction, which will catch up with players long after things have already happened. These systems are meant to function from the bottom-most level to the topmost level to produce this feeling of constant anxiety of systemic distrust.

SUPERJUMP: Do you mean systemic distrust from a character’s perspective? Or ludonarrative dissonance kind of distrust?

Spencer Yan: Absolutely both. There are things that players will feel that what they're doing is correct but the character will not. For example, there are certain places the character does not want to go but the player obviously doesn't know that unless they’ve read her logs.

Generally, I try to [model the game so that] if the player sees something or hears something troubling, the character will have a similar reaction. Sometimes what the player will find disturbing, the character won’t primarily because she is trained to deal with disturbing phenomena. But players will not always know that.

There's a test that you can actually take in the game. In the Outpost you can have her draw like a clock. She'll just walk up to the table, you press a button, she draws a clock and you look at it. Or she looks at it. She'll pick up the paper to look at what she drew. But then it also prints that screenshot to the players’ system folder for you to see what she actually drew. Typically, that will not always match with what she thought she drew because the game always takes place from her perspective. It's like there's always this level of competing perspectives.

"These systems are meant to function from the bottom-most level to the topmost level to produce this feeling of constant anxiety of systemic distrust."

Spencer Yan

SUPERJUMP: Have you ever played any of Kojima’s games like Death Stranding? Speaking of bodily functions and all of the mundane stuff that humans do that you won’t see in any other game, your approach to game design very much reminds me of Hideo Kojima.

Spencer Yan: I don't really like Metal Gear Solid games for reasons I won't go into. But as much as I don't care for it, I think Metal Gear Solid 3 is probably one of the most realistic depictions of military experience there is.

In combat, every soldier knows that shooting a gun is only a very small part of it. The majority of that is walking through all of these random [places] with all this massive weight on you. Like, where are you going to get food? Water? Can I drink from this river or is it contaminated? Am I going to evacuate my bowels every five seconds after drinking from it? I really like that about Metal Gear Solid 3 in particular.

I have mixed thoughts about Death Stranding, though. Again, I think there are certain aspects of it that are really interesting – ones that I wish were not paved over by the main gameplay progression in that game. But at the end of the day, I respect Kojima. I find a lot of the praise for some of his stuff questionable. But as a game designer, he's solid.

SUPERJUMP: Can you describe what's the actual gameplay loop of My Work is Not Yet Done? And if it has changed in any big way during the four years of its development.

Spencer Yan: So My Work is Not Yet Done originally started out as a hardcore survival game first and foremost. There was no narrative. It was just, you're a person in the wilderness. That's why I built all these extremely detailed simulations of fire-making - before, you could make all these little shelters and dig various fire pits. There are various ways of digging a fire pit which results in different levels of smoke. There was a period in the game where if it rained, and if you would go and collect leaves, it would produce thicker smoke; you put in plastics to produce black smoke. It used to be this very hardcore survival game.

Then I was like, 'I'm going to add a story because I need this to sell on Kickstarter.' [laughs] If I stuck to that version of My Work is Not Yet Done, it would have been out in late 2021. Unfortunately, I did not.

Now the main gameplay loop is this investigative horror thing. The primary gameplay loop of the game basically revolves around looking at and maintaining a number of sensors in the world. Or at least that's what the player is going to be doing.

But the day-to-day gameplay will be almost identical to what is in the gameplay demo, except you will be spending more time sitting at your computer in the game. Then the rest of the stuff will be based around maintaining your ability to operate those tools. At the end of the day, she's a scientist. Everything else that happens around that [gameplay] is in service to it. Stuff like going to the bathroom or finding food, of which there are multiple ways of doing. One of the ways is: there's an incredibly detailed worm farm in the basement that you can operate; you can pick out individual worms out of the dirt, run them through the sifter, put them in the oven and wait in real-time for them to cook; then you place them into a grinder and carry it off and load into the sifter...

There are a lot of these very granularly designed systems in My Work is Not Yet Done, which are meant to emphasize the fact that there really is nothing to do here. She's in a remote outpost and there's nothing to do but work.

Another big thing that players can do is participate in recreation for her sake. She can exercise and read. But all of these things are balanced against the fact that the game has a limited time span. My Work is Not Yet Done takes place on a fixed timeline in which there’s a certain amount of days. After that, the game ends for reasons that I won't get into. But what the player does with their time will determine how their sense of the plot progresses.

For example, if you want to know what happened to her team over the course of their admission, there are about 80 pages of blog entries that you can read through in the game. [laughs] But that means you'd have to sit there and have her sit at the computer reading logs (with the content she already knows) that won’t advance her plot in the slightest. So it will advance the players understanding of it, but the game will end with her not really advanced in any way because she's just been sitting there reading. The way I've designed My Work is Not Yet Done should accommodate every possible approach that I can predict.

"In combat, every soldier knows that shooting a gun is only a very small part of it. The majority of that is walking through all of these random [places] with all this massive weight on you. Like, where are you going to get food? Water? Can I drink from this river or is it contaminated? Am I going to evacuate my bowels every five seconds after drinking from it? I really like that about Metal Gear Solid 3 in particular."

Spencer Yan

SUPERJUMP: You were saying that each playthrough will take a limited time. How much time we are talking about? And can you start another session afterward?

Spencer Yan: You can replay the game. But when the game ends, it just destroys your save file, so you can just restart it and play through it again. There’s not supposed to be any permanence to it.

SUPERJUMP: And is there any sort of fail state in the game?

Spencer Yan: I would say there's no fail state. The only failed state that I can think of is if the player comes to the game and refuses to engage with it. That’s something that I have no control over. But as long as the player is willing to come to the game and set an objective for themselves, let's say to survive as long as possible – the game will still end (for reasons I won't talk about right now) and it will be considered a valid ending. My Work is Not Yet Done is designed in such a way that anything that happens to this woman is intentional.

SUPERJUMP: With the fear of sounding like a publisher - how much time does it take to beat the game?

Spencer Yan: You can finish the demo in three minutes I think. If you drag it out to the longest possible time, it’s probably eight hours per playthrough.

SUPERJUMP: I don’t want to pry into your personal life, but you were once training to be a priest. Is that right?

Spencer Yan: I'm actually back in the process of it.

SUPERJUMP: Does that mean that by the time My Work is Not Yet Done comes out you might be a priest? The first game developed and released by a priest?

Spencer Yan: Well, it takes a while. But it’s a possibility. I would be a priest who makes games for a living. Hell of a combination, I guess.

SUPERJUMP: That’s fascinating! What made you return to this path? Secondly, what's your relationship to priesthood, or to put it more bluntly, religion? Is there any way it informs what players experience in the game?

Spencer Yan: Oh man... So I wasn't born religious at all. My parents came from communist China where there was simply no religion. They believe religion is just nothing, just noise.

When I was in university, for some reason I became very fixated on studying medieval texts. I ended up doing my thesis on Hagiographic Narratives About Saints. effectively about the sex lives of saints, which I always thought was really interesting.

So my introduction to Christianity was very different. I've been in churches for non-church functions. I never attended service prior to becoming a Christian. I just read a bunch of theology basically. I studied my way into religion, for lack of a better way of describing it.

On my first go, I think I had an immature understanding of what being a priest meant. Again, my exposure to the church and Christianity was through scholastic theology. I read it like it was philosophy. And obviously, your average person sitting in a church does not care about scholastic theology. They do not want to hear about Supersessionary theory. [laughs] That was a very startling realization. That ended my run real quick.

These past couple of years I've done a lot of work as a lay chaplain for my church and prison. I found that I enjoyed dealing with all different kinds of people, including those who are severely traumatized by Christianity. Some people have gone to church their entire lives and have no idea about the fundamental tenets of Christianity. But it doesn't matter to me. What matters to me is that I'm able to sit down with this person and talk them through whatever it is they're going through.

I think in learning that process, I both feel the stronger calling to the priesthood and learned how to be just like a better writer or a better developer. The stuff that I enjoy about being a game dev is basically already that except it’s done through a video game and not a confessional thing for a sacramental setting.

As for the relationship between religion and my work, I would say that they're directly connected. This is going to sound crazy to people who aren't religious but for me, theology informs everything else. It's like, ideally, a good philosopher lives in such a way that everything else emerges as a result of the refinement of that philosophical process. This is one of the reasons why I resist the temptation of calling My Work is Not Yet Done a ‘cosmic horror’ game. Cosmic horror, at least the way I see it, is a very young and myopic way of dealing with existential struggles that religion, specifically theology, has been reckoning with literally since the inception of whatever religion you're talking about.

When it comes to cosmic horror, it’s usually like, ‘What if God was a tentacle monster?’ What if God was a bunch of sleeping aliens?’ To me that just feels like cosmic horror is an approach [to horror] when teenagers discover a common human phenomenon and they feel it anew - which doesn't limit the fact that what they're feeling is very authentic and genuine. But it’s just that it is not particularly backed [by anything].

But to return to My Work is Not Yet Done, I fundamentally see it as a work of theological horror. It's a work about confrontation with effectively the incomprehensible divine - the ways in which we don't understand how that sort of thing interacts with lives.

I mean, people talk about biblically accurate angels and that kind of stuff now. But that's not even scratching the surface. My favourite example is -

Spencer proceeded to discuss the comedically horrific tales from the Old and New Testament for the next five minutes. Here’s an excerpt:

In the book of Ezekiel, the prophet is just this village idiot who's living on the side of the river. Then one day, the sky opens up to him and [God’s] like, 'Hey man, eat this scroll.' He takes the scroll from his divine hand and eats it. What the scroll does is basically God’s way of symbolically enacting the siege of Jerusalem on this dude's body. So for a bunch of days and nights, Ezekiel is forced to sleep on each side of his body. It gets so bad that he develops tuberous bedsores and is forced to eat excrement. He then goes out in the town square and starts tearing out his own hair. And all that because the future prophecy is being enacted through his flesh.]

Waiting out rain #gamemaker #screenshotsaturday pic.twitter.com/MfisBZ3Hte

— Spencer Yan (@spncryn) October 7, 2023

A big part of the game is about the player sort of figuring out why [Avery] is there, what she is doing there. It involves this vision/encounter that she has in the desert. She's an Inquisitor - that was a very intentional choice on my part to frame it so it's not just a scientific expedition; there's also a theological and philosophical element to it as well. And I want it to kind of slowly dawn on the player rather than just being outright, like Warhammer, being like, 'Look, these are super Catholics who also happen to be a genocidal military faction.'

What I'm trying to do with my work is sort of portray a more nuanced idea of the world in which religion is very important. At the same time, one that is not one-dimensional.

SUPERJUMP: What are the inspirations behind your game? I know for a fact that "Dante's Inferno" is a big one.

Spencer Yan: ["Dante’s Inferno"] was not really an inspiration to me - I only wanted to refer to in order to set the tone for other people, if that makes sense. I kinda regret using it now...

The most obvious influence is Tarkovsky’s film adaptation of Solaris. I think Tarkovsky is also someone that, similarly to Kojima, a lot of people focus mainly on his work as a filmmaker. For me, a greater interest lies in Tarkovsky’s intense religiousness. I watched Solaris in a religious sense. That influenced me heavily.

Then, obliquely My Work is Not Yet Done is also inspired by the Old Testament’s accounts of human encounters with Divine Manifestations.

Are you familiar with Karl Ove Knausgård’s six-book series called "My Struggle"? Well, he was just living an ordinary mediocre life. One day he decided to write an extremely detailed auto-fictional account of his life, starting from the incident when he was very young up until his first marriage. He didn't omit any names; there's no blurring of names because Knausgård believed if you would change the name of your uncle, then it wouldn't be your uncle. And the things he wrote about were not particularly flattering either.

There's a 200-page long bit where he goes to a birthday party for one of his children. And he's sitting there feeling infirm because there are all these fairly attractive mothers with their children. And there he is, this kind of older, disheveled dude. The only thing he has to his name is that the entire world now knows about his erectile dysfunction and his family's drinking problems... It’s so boring but so interesting.

Knausgård is also deeply obsessed with Christian mythology. He's not even a Christian but he published a translation of the New Testament. He also wrote this book called "A Time for Everything" which takes a similar realist approach to foundational stories in the book of Genesis, for example. 'Why did Cain rise to the occasion and kill Abel? What was it like to live during the final days of the flood?', you know.

All these little stories are told within this larger frame about this 16th-century theologian who came across two extremely weakened angels that he saw bathing. Then his life work became chronicling angels. So, "A Time for Everything" was another major point of inspiration for me.

In terms of the design of the world and everything that is happening in it, you could say Pathologic. But just as equally Dead Rising games. That was the first time I ever came across a concept where you're on a fixed time and have this open environment, you can just do whatever. And people will die if you don't get to them in time; you could be doing something that someone else somewhere in the world will die of. I was 15 and this stuff just blew my mind. I didn't think this was possible in games. Pathologic games then are just the more sophisticated, more grownup version of that.

My Work is Not Yet Done is also heavily influenced by Dear Esther in ways that I will not reveal until the game is out.

"I fundamentally see it as a work of theological horror. It's a work about confrontation with effectively the incomprehensible divine - the ways in which we don't understand how that sort of thing interacts with lives."

Spencer Yan

SUPERJUMP: When should we expect My Work is Not Yet Done to come out?

Spencer Yan: Well, a lot of the stuff that I've been doing recently is figuring out what I want to do with game development – you know, having lost my publisher and having to figure out what to do with My Work is Not Yet Done. Especially since Sam [Tudor] is on board – I can achieve things that I didn't feel could be achieved on my own.

I've been writing a tabletop role-playing game actually. A series of campaigns that take place in direct relation to My Work is Not Yet Done. It centres around a similar operating team under similar circumstances. My goal with that is to basically provide players a kind of stepping stone into this world where they will be able to acquaint themselves more with organizations and government entities that characters in this game are operating with.

SUPERJUMP: So the book is coming first?

Spencer Yan: Yeah. Mostly it’s just an interim project. My goal is to have a printed book done by the end of this year. Honestly, I need to do it for the money. And I just want to do it because I think it's pretty cool.

So far it’s been an interesting project to work on that really helped me to clarify some ideas about the story of the game.

SUPERJUMP: That means we probably won’t see My Work is Not Yet Done this year?

Spencer Yan: Definitely not. Unless I either release an awkward finish - which I'm not planning to do - or find a way to build a time machine, that’s not going to happen.

The following chat with Sam Tudor, My Work is Not Yet Done composer, occurred via email a few weeks after my initial interview with Spencer. Here's what he had to say about his contribution to the project:

SUPERJUMP: What was your reaction when Spencer approached you with the proposal to join the project?

Sam Tudor (composer): Initially it was me who reached out to Spencer - although not necessarily to work on this game.

I liked his work and was just interested in learning more about game creation in general. We had a video call which led to many more calls over the course of the pandemic. Obviously, that was a really isolating time for many people, so it was nice to meet someone new at a time when everyone was stored away at home.

When we started talking about music for his game, I felt excited because I think we share similar aesthetic tastes. I was inspired by the visual element and felt I knew what it asked for, in a sonic sense. There is a real darkness to the entire project, which intrigued me as a space to go into.

SUPERJUMP: Was it difficult to convince Spencer that his game needs music? What's your relationship to video games?

Sam Tudor: Hmmm. I would say that while it wasn’t necessarily difficult to convince Spencer the game needs music. It was important to establish that I wasn’t going to try and make something extremely melodic and "song-y", because that’s not what the game needs.

Spencer has a clear aesthetic vision and I know he is very careful about what exists and doesn’t exist in this world. What the game asks for is a kind of anti-composing, in the sense that we don’t want to create something too lyrical, or too obviously written - it’s more just a series of sounds and tones that blend the diegetic and non-diegetic. The goal is to create a sensation more than anything particularly recognizable or melodic.

If I remember correctly I sent him a 6-minute ambient piece that I had made, and I think that convinced him we had similar taste and I wasn’t going to send over some massive Final Fantasy orchestral music or anything like that (I love the Final Fantasy scores, by the way).

"Spencer has a clear aesthetic vision and I know he is very careful about what exists and doesn’t exist in this world. What the game asks for is a kind of anti-composing, in the sense that we don’t want to create something too lyrical, or too obviously written - it’s more just a series of sounds and tones that blend the diegetic and non-diegetic. The goal is to create a sensation more than anything particularly recognizable or melodic."

Sam Tudor

SUPERJUMP: Have you previously made music for games?

Sam Tudor: During the pandemic I discovered itch.io and the game jam community. I wasn’t involved with the game dev community in any way before that. But I had known for a while that I wanted to try my hand at video game music. I work as a film composer and have done music for different styles of film, but I wanted to try something that was a bit less linear and wanted to try creating audio that has to exist with / be responsive to player input.

The indie game community I started working with via itch.io and Discord were so supportive and generous, and I ended up making quite a few compositions for really short games in that context. That being said, this is the first full-length, "to-be-published" project like this that I have ever worked on.

SUPERJUMP: What are your main inspirations for the music of My Work is Not Yet Done?

Sam Tudor: I’ve noticed that when I’m creating the sounds for My Work is Not Yet Done, I’m always thinking about some kind of entity. What if these radio transmissions had a life of their own? What if there was some kind of cognizant being buried in / made up of thousands and thousands of radio signals, old archival recordings, and leftover sounds? I think imagining this sort of ominous presence kind of informs how I do things. I think Spencer’s work invites this kind of thinking.

SUPERJUMP: What's the hardest part of making music for a project like this?

Sam Tudor: The unique challenge to composing for this game is simply the fact that it’s not really a game that asks for music, and "music" isn’t even necessarily the goal.

What’s interesting is that Spencer and I are working in tandem - the game isn’t finished, so sometimes I am creating soundscapes for worlds or spaces I haven’t seen yet. I usually just peruse Spencer's documentation and start creating something when I hit a piece of text that resonates with me. I don’t know where / if the thing I make will end up in the game. There is a certain vagueness to that process which can be a little unsettling, but I also think that process is a perfect match for the tone of the piece, and the effect of working that way is net positive.

So to answer your question, I think the big challenge is putting aside any more traditional approaches I have to melody and composition, and just embracing creating these broad, mood-based "shapes".