Music Lessons: Grief and Hope in When the Past Was Around

Memories, and the grief that accompanies them

When the Past Was Around is a short game, one that can be completed in a little over two hours. It features clean point-and-click gameplay and simplicity of art, music, and design that allows its principal story to progress unfettered and with due care. Even in its short run it allows for moments of pause to reflect on powerful scenes and offers a leisurely embrace of smaller ones.

The game was released in 2020 by Mojiken Studio, the same folks behind the more recent A Space for the Unbound, which was reviewed by SUPERJUMP's Brandon R. Chinn after its release in 2023. When the Past Was Around is a narrative-focused game that takes players through the depth of grief in a soft-lit way, illustrating with brevity and clarity how loss becomes us and how we, in mourning, come to exist in a reality composed entirely of its memories.

Healing Through Passion

We begin the story as Eda, a young woman who loves music. We learn quickly of her mysterious partner, known only as Owl, and then, right after, we learn of his death. He is only a dark shadow at first, a shade in her memory, but eventually, we see the fully realized character. In the game's dream-like opening, Owl walks Eda through a door and gives her his violin, but when Eda touches this vital part of him it is a painful, jagged experience, and we are transported then to the desperate scene of her loss: a cemetery, where his music notes play hauntingly from behind the cold stone of a mausoleum door.

The game does not keep his death a secret, as I thought it might, making attempts to subvert our expectations of how he died. There are hints early on that he is sick - he holds at his head, only to smile when Eda approaches as if the pain is merely a small inconvenience - and we, the audience, understand this as factual foreshadowing. We know at the onset that we are playing a character experiencing loss and so we understand that she must have something to lose.

In the beginning, we see Eda's bright, happy girlhood transformed into sullen young adulthood. Her passion for the violin is doused by an unnamed number of things and then, with finality, by the loss of Owl. In the first memory we visit, before even meeting him, she breaks her own instrument, leaving it smashed on the floor. She only leaves her apartment, after tidying up a bit, when she hears the soft twine of a music box playing what we come to know as Owl's motif.

This introduces us slyly to the game's real throughline: to bring Eda back to her music. The game does not do this only by employing grief as a vehicle but by illustrating that sometimes our greatest struggles ground us to the people we used to be, who we might have forgotten about in the height of life's rush, and that, through loss, we come to rediscover as requisite. The game depicts Eda often floating along in her own memoryscapes, airily drawn to notes of music. She encounters Owl in person after witnessing him play at a pediatric center, and it's telling that his first act is to provide her his scarf - a symbol of him that is present throughout - to warm her after she shivers.

We experience Eda's memories of Owl as a series of vignettes, all set against backdrops that, while initially vibrant, take on a stormy, claustrophobic feel as she moves through her grief. Each memory is provided through a feather that is "unlocked" after completing the puzzles of a level. At the end of each memory with Owl she is then whisked away, wearing black, to a room in which unpacked boxes hide the treasures of their relationship. At the edge of this room sits a large birdcage that holds a dark figure we know to be Owl, albeit a version of him she cannot accept. It is up to us to help Eda move through her memories to process and reclaim them as parts of herself, parts of Owl, and parts of their shared life that she will have to carry without reservation into the future.

The Little Things

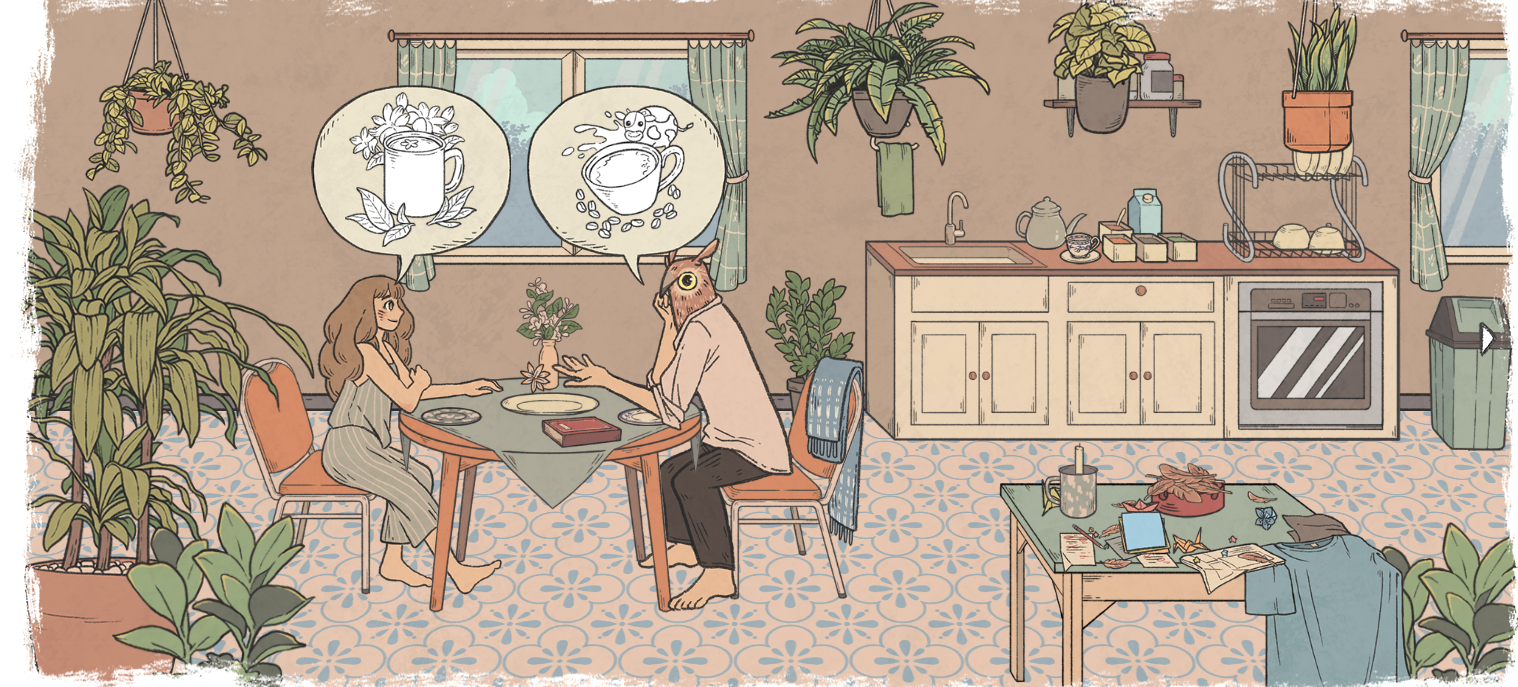

The game is beautiful for its particular attention to the quaint details of everyday life. It is the shared mornings of coffee or tea, the snapshots taken on outings to the beach, and the quiet domesticity of cleaning or laundry that paint a picture of bliss. The idyllic history she has with Owl feels almost too tuned to emotional resonance. He is a kind, thoughtful, happy, and ultimately a terminal partner, one that we see only through Eda's eyes after his death. It is his near perfection that feels resolutely crafted from memory, as if in his passing he's attained a certain sanctity, serving as a ghostly reminder of all the things that Eda could do if she would only learn to let him go.

These moments are exemplified by his sudden disappearances, leaving Eda a trail of feathers to follow, and her subsequently frantic search for him. The music changes instrumentation throughout the game as well, growing more muted or out of tune as we near the climax of their parting. You even have the option to turn off and on the music at one point - a fun little diversion, but also illustrative of how powerful the silence now feels.

Towards the end we get a sequence where Eda is left alone and swathed in the sepia-toned aftermath of loss, picking through their cherished memories to find balance and, eventually, her way to healing. We see Owl's sketch-style imprint on these memories transform to rock when we click on him, relinquishing his existence to being now the weight of Eda's grief.

At first, it seems as if we go through these moments to overcome them and get past their allure, but as Eda listens to his music box she comes to see the memories for what they are: beautiful pieces of them to be known and celebrated and grieved. When Owl finally bequeaths his violin, we see Eda hesitantly reach for it and then play her own song - a harkening back to the self-neglect of her talent, now fully realized in his final gift to her. In playing she breaks the bars of fear to fully embrace the fact that Owl is gone, and yet he's also ever-present in their time together.

There's also a subtle element of destruction in the game that seems anathema to its artful and delicate gameplay, and I was shocked the first time I touched a plant or a bookshelf and saw the violent ramifications of the click. I felt clumsy, so easily knocking over a precious vase or mucking up a carefully curated bookcase so that the tomes landed in open-faced piles on the hardwood floor. But as I experienced the final scenes of Owl's sickness, in which Eda has to find his medicine, there was a stark distress to the destruction, a sensation of searching for the impossible at any cost that felt wholly and organically real.

And as you move towards the end you are afforded the opportunity of more wanton destruction, but this results in revealing pieces of Owl's musical composition for Eda to collect. It is a way forward, seemingly through the rage. This dark transformation of once-beautiful memories is what fosters Eda's longing and impedes her healing: in the absence of those we made these memories with they feel retroactively empty, melancholic, and the very act of reliving them is destruction in and of itself.

As the credits roll we see Eda and Owl, two people who loved each other and their music, playing one final, symbolic song together. Our last image at the end of the credits is Owl vanishing for good, leaving Eda only with his scarf. She looks out into the distance, thoughtful, and we fade to white. It is a beautiful ending for its understanding of grief's quiet permanence - there is no smile on her face but a realization that even braced by hope, there are still going to be moments in which we miss what was.