Minimalism in Mouthwashing

99% of horror is in the imagination

They say fear comes from a lack of knowledge. I agree. I think fear comes from knowing just enough information to make a guess, but not enough to be sure. In that long distance, between what if and what is, that is where fear is. In the book What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, the author describes actions without providing explanations. The characters’ thought processes remain hidden from the readers. None of the people within can clearly communicate their intent or what their love means. There are no expositions, making who really loves who anyone’s guess. This ambiguity leaves it up to the reader to make heads or tails of any events implied. In that uncertainty, there’s an unsettling air in every tale, as if everyone has ill intent. When a character suddenly kills two girls, there is no inner monologue, only the actions as they are — a verb with no adjective.

In the game Mouthwashing, by Swedish developer Wrong Organ, the same philosophy applies in a different medium. Actions are taken, and nightmarish visions are seen, yet the driving force behind them remains unknown. We can deduce from clues, interpret, and try to understand, but never completely comprehend. In this gap of knowledge hides the horror.

Mouthwashing features five characters, members of a delivery crew stuck in their space freighter, the Pony Express. Named after the American Express mail service from the 1800s, this fictional company experiences failure similar to its real-life counterpart, one that is marginally more awful.

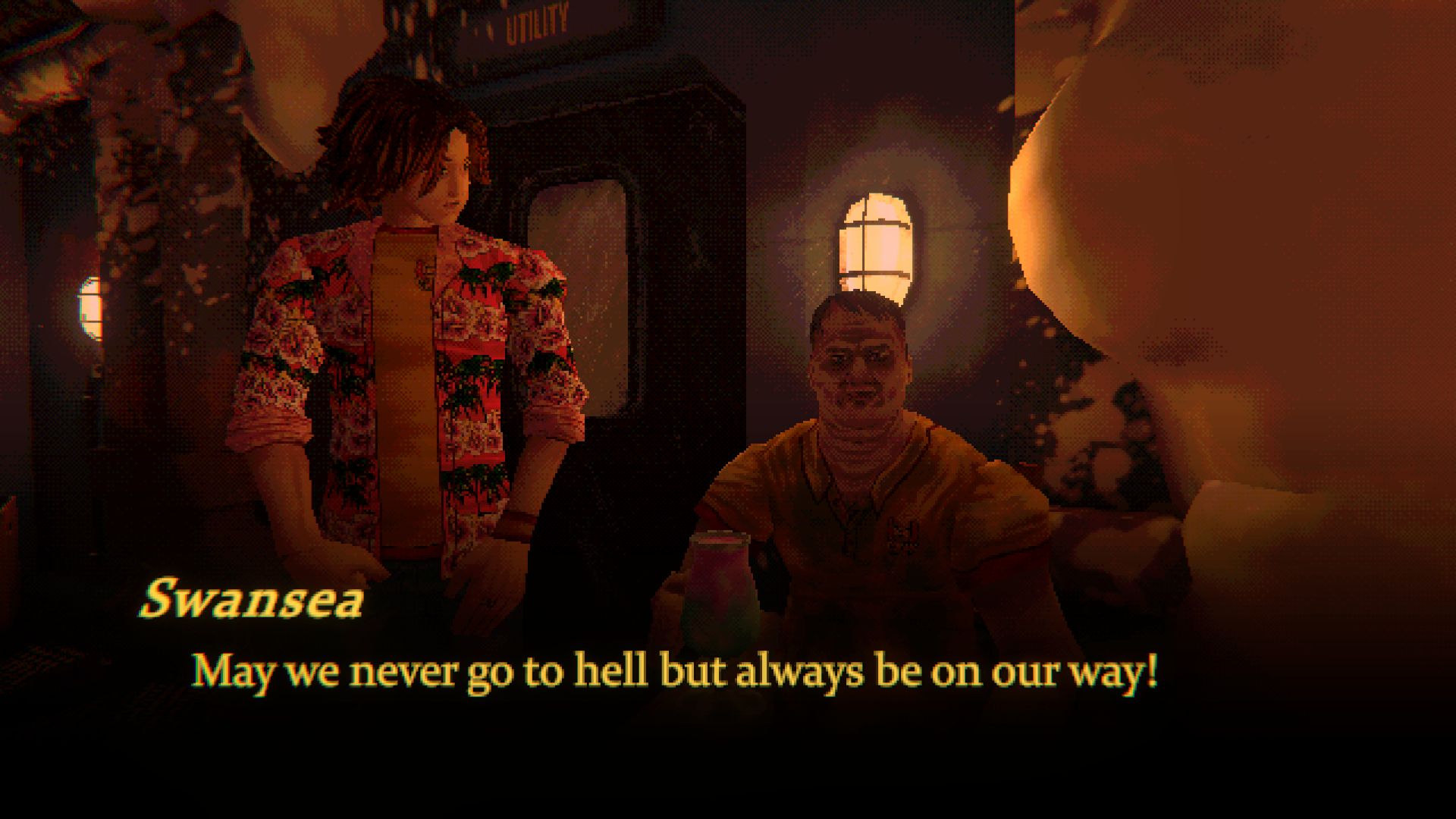

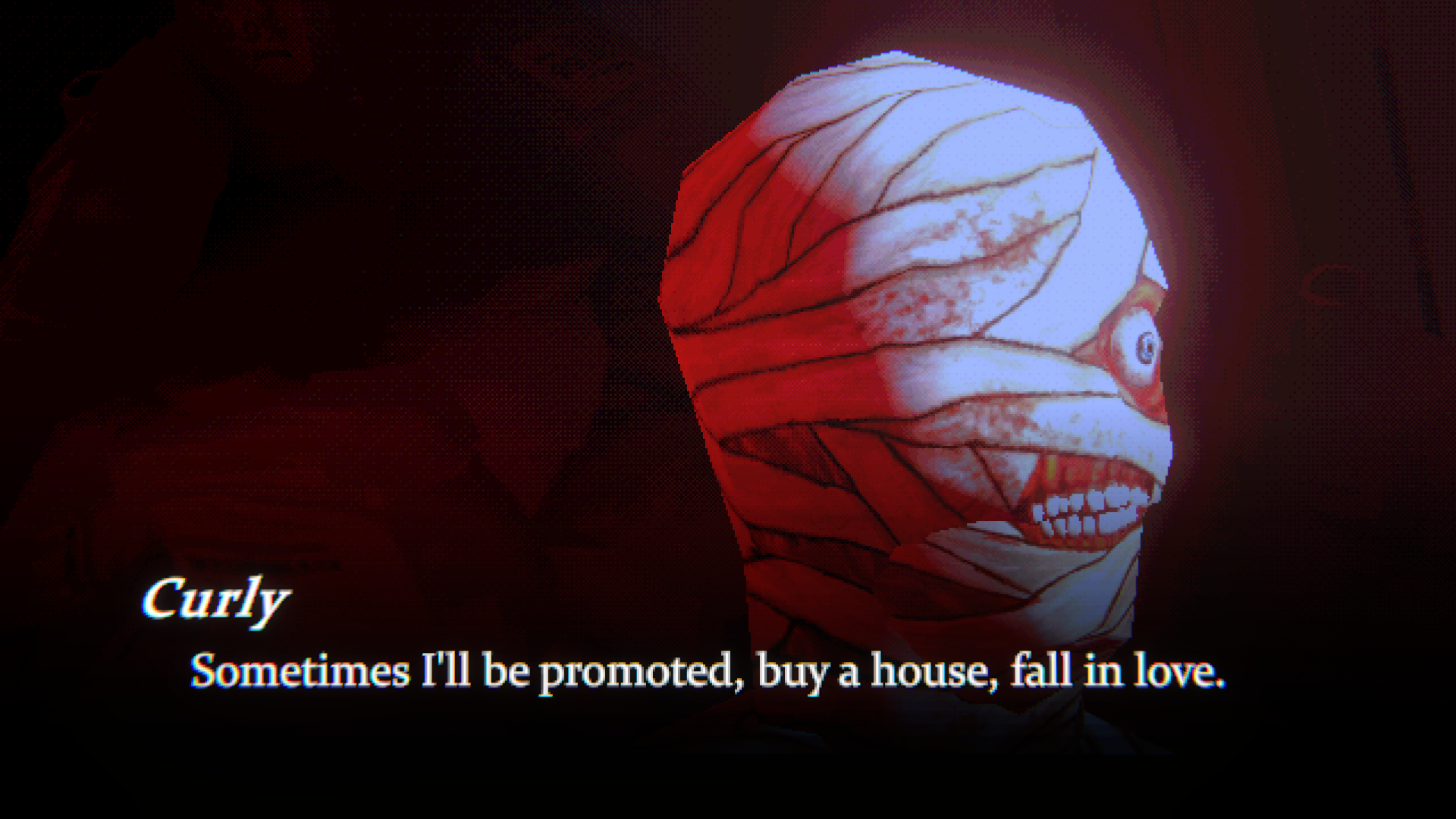

Curly is their disfigured captain, whom the player controls in flashbacks, before the crash. Anya is their timid nurse. Daisuke is the young intern. Swansea is the drunken senior. Last but definitely not least, Jimmy is the new captain whom the player controls in the present. Each captain says words to comfort others and rationalize their actions, but in the end, the impression the latter leaves is of a narcissist, believing things that are not true to avoid responsibility.

Actions are taken, and nightmarish visions are seen, yet the driving force behind them remains unknown.

Limitations surface great horror

Told non-linearly, the player needs to piece together dialogue from when Curly was behind the wheel to when Jimmy and the crew survive on dwindling supplies. Only then can we understand what happened, what led to the crash, and who the crew is. Most of this information is not directly communicated; we infer from the words spoken, and for the cruelties hinted between the lines, we imagine horror after the fact.

As the crew descends into space madness, important events throughout the ship follow the furtive dogma of the dialogue, holding back on unveiling the characters’ fates. It’s not only their biographies that are partly redacted, but also their headstones. The player learns that the company employing them sent a letter to lay off the entire crew, and we experience this revelation along with the crew. The news is teased before it is confirmed, giving us ample time for anticipation.

Mouthwashing emphasizes minimalism, applying it not only to the information presented but also to the method of delivery, especially its rudimentary audiovisual design. For instance, Anya has tried and failed to get into medical school, and the impact of being out of a job is not clear from her polygonal face, but it is obvious to assume. She has a permanently wistful facial texture, and all it needs is a couple of short lines or hands moving to hide her mouth to let players conclude on her reaction.

Being an indie game, there is a lack of budget for high-fidelity detail or gratuitous renders, and that is to the game’s benefit. There are no voiced lines, apart from the mascot, and Curly’s cries of pain every time Jimmy shoves painkillers down his mouth. The scene’s context, the character’s unmoving faces, and the player’s interpretation all work together to reveal each character’s tone of voice. In the games' short 2-3 hour runtime, most essential character fates and decisions happen off-screen, in cut-to-blacks and filled-in sound effects. The player sees only the beginning and the end, leaving the details in between to their imagination. It works like brief outlines of events in a book which, without a direct visual, lets the act fester in the back of our heads.

Mouthwashing emphasizes minimalism, applying it not only to the information presented but also to the method of delivery, especially its rudimentary audiovisual design.

Scary things need a scared person

"To kill a man between panels is to condemn him to a thousand deaths."

Scott McCloud

In Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, writer Scott McCloud examines the formal construction of the gap between panels and the reader’s part in giving it life. Without readers, horror comics are just a series of separate images with words in them. Read sequentially, an image of a killer winding up their axe next to an image of someone’s zoomed-in face beside a sound effect means more than they do on their own. But how brutal the impact is, and the location of the wound, that is all up to the reader.

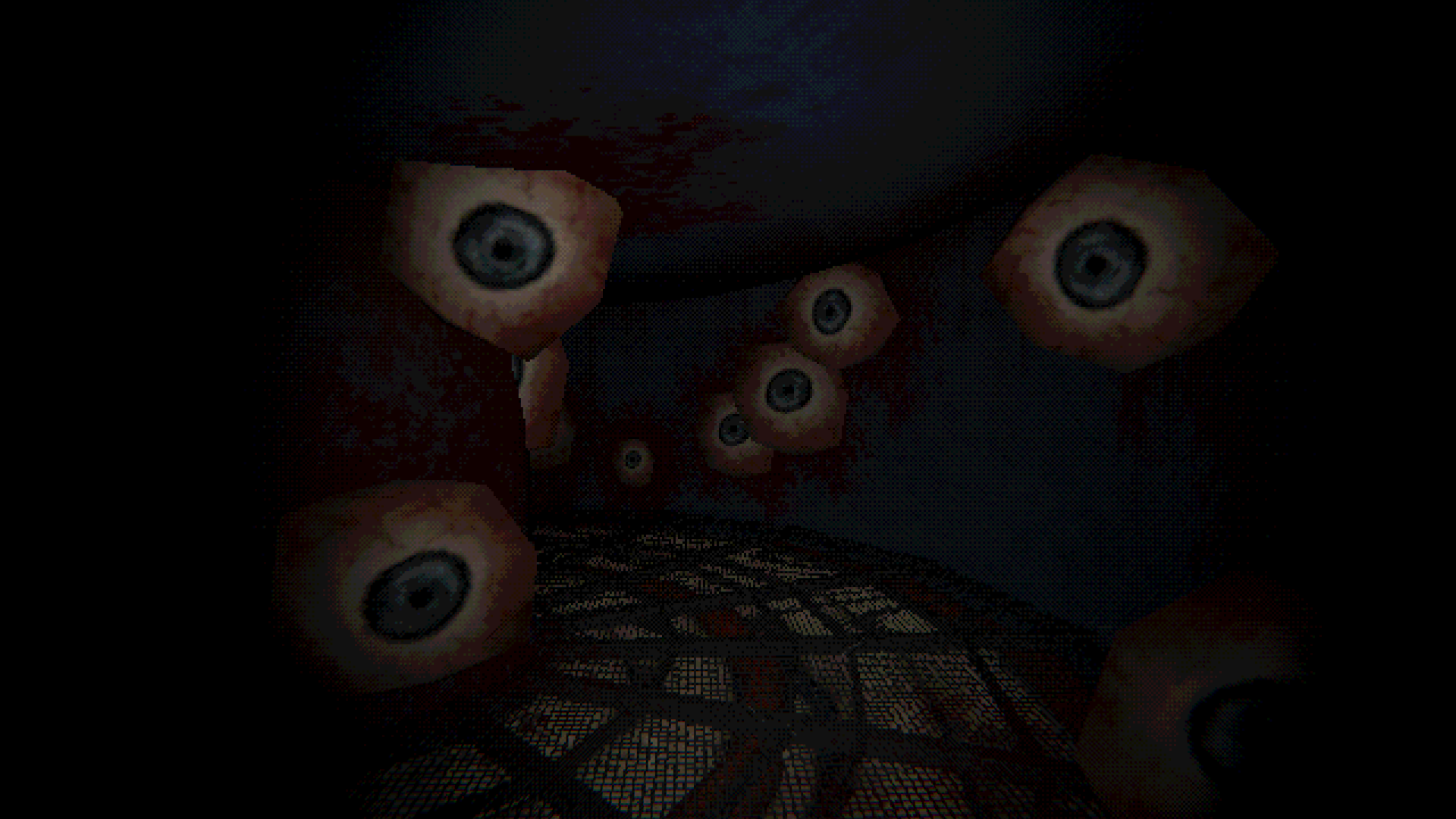

It’s not dissimilar to how horror is effective here, where the game is a lenticular painting that needs someone to view it from different angles to make the image move. Here, a closed door is benign until the player looks behind it. The ship is well until you push a button that steers it to its doom. Curly is silent until you feed him his own flesh. It is a horror not by its setting or visuals alone, but through the fact that the player’s actions are horrific, and we can only passively act it out. When there is only a black screen and someone screams, we hurt the person a hundred different ways in our heads before we see what happened.

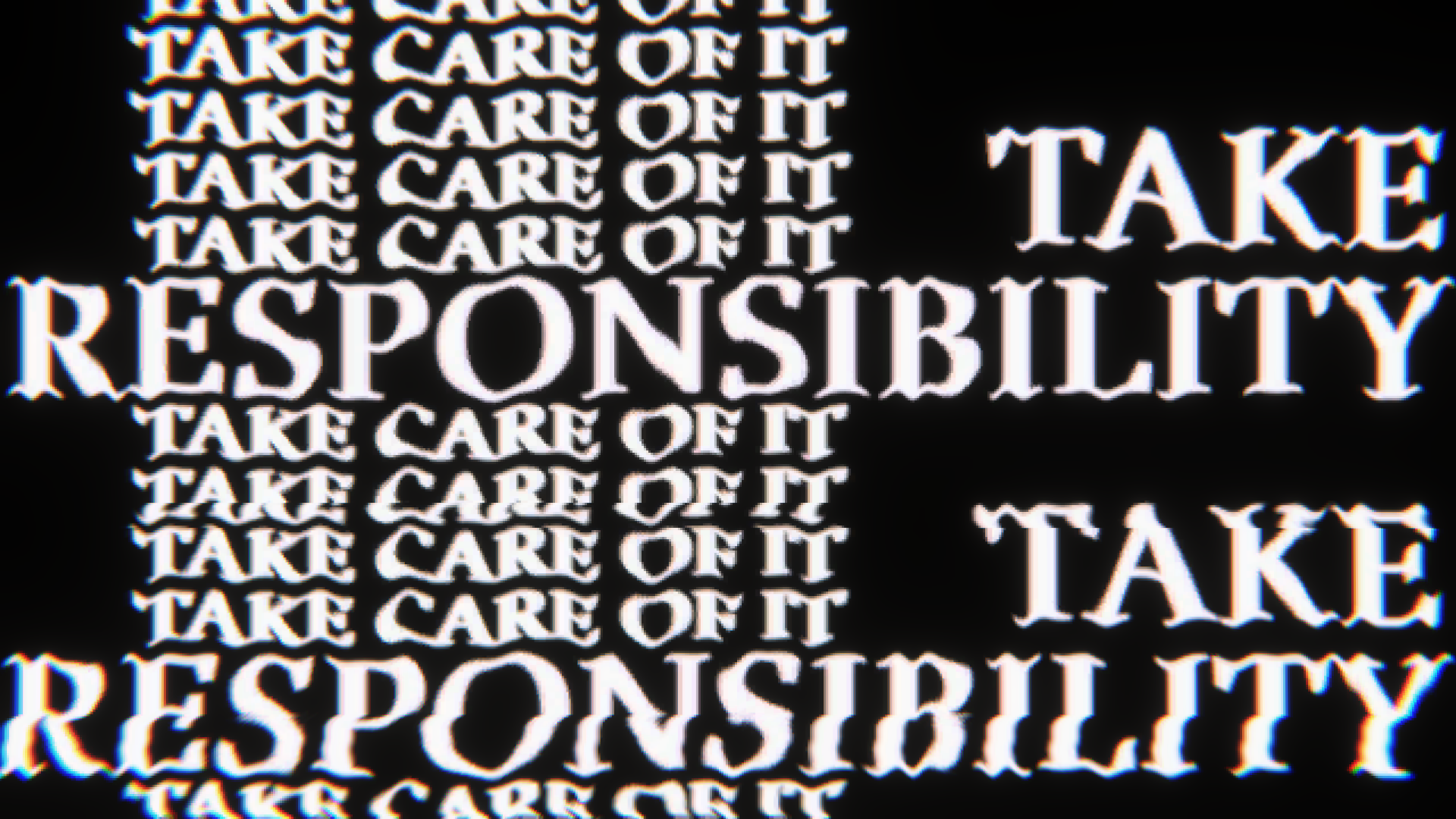

After learning about his impending unemployment, Jimmy shifts the blame to Captain Curly and portrays himself as a victim, avoiding accountability from others—and, most importantly, from himself. In a twist, Jimmy, whom the player controls for most of the game, and who we thought was the protagonist, is in fact the extreme opposite. He is the selfish catalyst of every other character’s demise.

This is most clear in Anya’s fate. Near the end, but before the crash, Anya reveals to Curly that she is pregnant. She strongly implies the child is the result of sexual assault. The details do not seem to matter to the captain. He doesn’t ask for elaboration, and maybe if he doesn’t, then he’s not culpable; ignorance frees him from responsibility. He only states he will talk to the father, who is later revealed to be Jimmy.

This realization leads to the player retroactively recognizing breadcrumbs from Anya’s earlier conversations. For example, at the game’s beginning, she didn’t want to talk to Jimmy for his psych eval, joking about it, and later inquired about locked rooms on the ship. Unlike jump scares, the horrific reaction to this information is not because of the sudden shock of the senses, but the conscious omission of information that is gradually added later. This is the basis of all the horror in Mouthwashing, the ones that don’t just make you jump from your seat for a second, but make your hair stand until you sleep.

Here, a closed door is benign until the player looks behind it. The ship is well until you push a button that steers it to its doom. Curly is silent until you feed him his own flesh.

There can be an argument that what happens to Anya is a loathsome narrative trope, but that it isn’t explicit, and that the extent of the cruelty is wholly up to players’ imaginations, makes it in line with the rest of the game and Jimmy as a character. It is something so matter-of-fact, the realization so late, that it leaves the player powerless. One inhumanity incites the whole catastrophe, certifying Jimmy as irredeemable to the player and himself. The single act of unwittingly bringing a child into the world makes the narcissist’s reality crumble around him. To escape, he must create a new reality of his own where he’s not responsible for a life, let alone his own.

In the end, Captain Curly, who benefited most from being laid off, instead sacrifices himself to prevent the crash, while Jimmy brings the whole crew down with him. It's all to fit his delusional worldview and his perceived self until even that is unsuitable, and the only action that fits with his self-perception is suicide. The ultimate escape from responsibility; his last resort.

Minimalism gives Mouthwashing’s story two different meanings: one experienced right away as the story plays out, and one that is understood in hindsight, after detail is given. The most explanation we get on what the game is about and what motivates the characters is from phantasmagorical body horror sections. These surreal dissections of the soul show us, including but not limited to, the all-seeing eye of corporate brands, the eyes of personal guilt, and how corporations are an entity devoid of responsibility, handing such things to ill-equipped men with neuroses. That's plenty of interesting visuals and rich themes for a two-hour game.

Minimalism gives Mouthwashing’s story two different meanings: one experienced right away as the story plays out, and one that is understood in hindsight, after detail is given.

Low budget leads to high-pitched screams

The horror genre has always been synonymous with low-budget, from the highly successful films Paranormal Activity and the Blair Witch Project to games such as Slenderman and Five Nights at Freddy’s. Limitations easily birth horror, the ambiguity from not knowing whether something lurks behind you, out of the corner of your eye, or whether your senses deceive you. When we hear sounds on the black screen, but see nothing, experience tells us that something terrifying might be occurring. Our natural fight-or-flight system kicks in, and our paranoia scares us. Our body becomes our enemy, engineered against us. Our instincts betray us by working too well.

As we construct these disparate moments, separated by black screens and incomplete dialogues, we discover late the horror of what the captains of the Pony Express have done or what awaited them. Peek-a-boo, we open our eyes, and the crew dies. Without clarity, the player takes part in the scene’s direction. There is a foundation for a scene, the characters’ polygonal faces and modest animation, the text feigning as spoken dialogue, that the player can finish in their heads. Because we’ve partly created it, the fear lingers easily, finding a place to rest in our daydreams.

Video games, perhaps more than books or comics, can take advantage of minimalism to a more visceral extent. Mouthwashing proves that the resurgence of low polygon PS1-style graphics makes way for novel experiences. It is not only for boomer shooters or short atmospheric walking simulators; ;this graphical style can tell a compelling horror story as well, one that asks questions and leaves the player with questions in return. Questions of responsibility, of corporate working conditions, and of life itself. Amid those ruminations, the player might carry something with them—a small, subtle thing. Something they might not notice immediately but can’t shake once they do: a lingering aftertaste of dread.