Men Without Women — Feminism and Trauma in LISA: The Painful, Part 4

Contrasting the male "ideal of femininity" against real-world relationships

After three articles delving into LISA: The Painful, I’ve realized that the plot is built on the foundation of several core ironies. Brad Armstrong embarks on a harrowing, often violent quest to save a girl who doesn’t want to be saved, ruining her life in the process. Buddy Armstrong rejects Brad to escape toxic masculinity, only to join another gang of patriarchs in a futile sense of agency to make one bad choice over another. I’ll add another irony to the pile, and this is the most important one to understanding the plot: Men obsessively worship the ideal of femininity, and yet they hate women.

To best explain the ramifications of this irony, I’ll start in an unexpected place: What’s with all the cross-dressers? From random NPCs to the recruitable party member Queen Roger, to Brad himself, cross-dressers are a prominent subculture in Olathe. For someone as defensively masculine as Brad, the game sure puts him in a ton of scenarios where he’s in full drag: There’s the beginning of the game where Buddy does his makeup. Then there’s The Beehive, a club men frequent to have sex with drag queen escorts (a totally heterosexual thing to do), and Brad in a mini-game can be one of these escorts, lipstick and all. And then there’s the episode where Brad is abducted by a man named Jim who forces him to go en femme and all the in-game menus change Brad’s name to “Sexy Boy.” After that, you can put Brad in a dress anytime with just a few clicks on the menu.

For a game so interested in telling a story about masculinity, the game’s many pivots into drag femininity were the puzzle pieces that didn’t quite fit, but I think I finally understand. To some extent, it plays into the theme of Brad’s constant feelings of powerlessness and emasculation, but I think it goes deeper than that, explaining the masculine search for an ideal, impossible form of femininity in a post-apocalyptic world without women.

Note that I distinguish male crossdressers from trans women, who are women and express femininity according to their gender identity. There are no transgender characters in LISA. Now, to be clear, there are many reasons cisgender men dress and express themselves femininely. Harry Styles does it to challenge norms in fashion. Some like the softer clothing choices and the wider variety of women's clothing options. Others have feminine personalities, and that’s what they want to show off. Lots of people want to be pretty and feminine, and that’s totally awesome. However, there are other motives for dressing too that reveal wider issues in masculinity. So I took to the cross-dressing subreddit and got some interesting responses. These quotes represent a small minority of motivations, but ones that are directly relevant here.

“One of my theories is that the onset of cross-dressing is motivated by the desire for a feminine presence in one's life,” one lady said. “This would especially be true in the case of a bereavement or a separation.” Here are some others.

“After thinking about it I think it's actually because I miss women in my life.”

“In my singleness, I became a crossdresser and created a name for my female persona. I started learning to talk with a feminine voice so that I could tell myself sweet love things you would only get in a relationship. Whenever I dressed up as a girl I would video myself and talk to my male self this way.”

It seems like one motive for dressing is to compensate for something missing. Some cross-dressing men reach for female emotionality they might feel is inaccessible as a man when no women are in close proximity. It’s a way of seizing control over emotions the only way they know exists, through femininity.

In the Journal of Gender Studies, Gail Hawkes writes that cross-dressing was a way to escape militant gender roles. “The cross dresser was making a statement about their access to sacred spheres beyond the mundane contexts marked by accepted binary categories.” In other words, when gender roles are harshly enforced, and when emotionality is only acceptable for women, some men feel like their only option to embrace their emotions is to put on a dress and heels.

We’ve established that there’s a part of Brad deep inside that wants to open up his emotions and help others, but this doesn’t come easily. And yet he has little trouble donning a feminine persona to entertain male Beehive patrons so they can, for a moment, pretend to live in a world where women still exist.

This might be well-intentioned, but it does little to fix masculinity, for Hawkes argues that the decision to cross-dress in a world with restrictive gender roles is often “a twilight world of ‘choice’ exercised on the margins.” If men were fully allowed to express themselves emotionally, fewer men would have the emotional need to put on a dress, so the “decision” to cross-dress is on some level coerced by societies with rigid binaries.

To reiterate, feminine men are awesome, and nothing against the people who reject social pressures, are consciously aware that emotional expression can be masculine or feminine, and ultimately gravitate toward femininity. In addition to that valid form of expression, I think LISA is saying that masculine people need a space to express their feelings independent of femininity. Brad and the other drag queens at The Beehive are enabling the status quo where men only feel comfortable exploring their emotions with a feminine person. Reclaimed masculinity would end wars in Olathe and destabilize male fixation on women, but rigid gender rules preclude this possibility.

Are Women the Answer to Men’s Problems?

Here, we reach LISA’s most compelling paradox. The game’s cast and NPCs look at the woman-populated world before the flash with nostalgia, yet men weren’t happy back then either. Men are obsessed with the ideal of women, crave the emotional comfort they provide, would go to war for them, would die for them, would kill for them. And yet, every real woman depicted in flashbacks before the apocalypse is depicted negatively from a male POV.

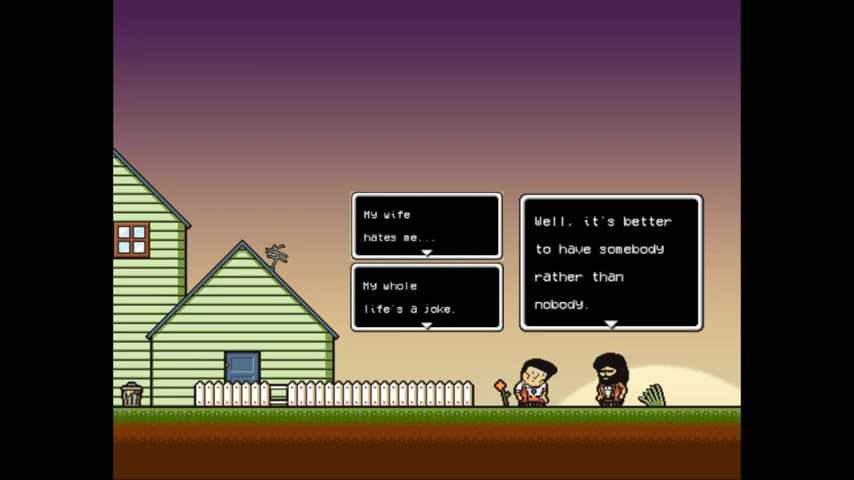

Take the eccentric historian Nern Guan, for example, in probably the funniest scene in the game. Nern offers to tell Brad the history of the world before the flash, but he keeps getting side-tracked, offering accounts about his rocking chair and his wife. Despite revealing no concrete facts about the apocalypse, Nern recounts the core of the history of masculinity: Nern insists that he loved his wife; but really, he hates his wife.

Nern tries to conceal this fact by insistently referring to her as his “sweet wife,” over and over. Yet there’s something about her that doesn’t quite measure up, like how she serves him bottled iced tea instead of making it from scratch, or how she makes a potato salad for a cookout when his archenemy’s “more attractive wife” brought a fruit salad. That’s when all pretenses drop and he point-blank asks “Why can’t I be married to an attractive woman? Is it me? Is it my bank account?” before calling his wife “mediocre” and a “dumb potato bitch.”

One has to ask – if Nern has so many problems with his wife, why did he marry her? The answer is clear – Nern sees his wife not as a human being but as a trophy he can show around to compete with other men. In this world of hyper-masculine competition that existed both before and after the flash, Nern was obviously a very sad person, with or without a woman in his life.

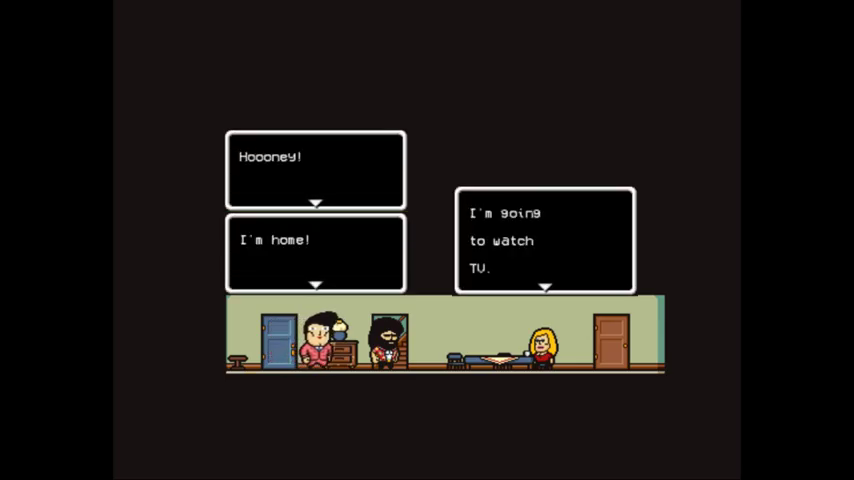

In another moment of nuptial malaise, Brad visits his friend Rick and is greeted by Rick’s indifferent wife, Shelly. Rick comes home in a suit after a hard day of work and asks if she has dinner ready, to which Shelly flatly says “no.” So he orders takeout and asks how his son is doing. Shelly: “Who cares.” That’s when Shelly’s son, “Junior,” a burly Black man, comes downstairs, with the implication being that Shelly cheats on Rick. In every imaginable way, Shelly fails to embody the characteristics of a “good wife,” leaving Rick unsatisfied. While the game’s portrayal of a racist trope about cuckoldry is potentially problematic, it reveals an irrational, at times racist fear embedded in the white male gaze that women will leave them for stronger men. It reveals a buried paranoia held underneath an obsessive search to own and control an impossible woman displaying idealized femininity.

I wonder if this is why the initial wave of reviews branded LISA as “antifeminist.” The takeaway might, after all, be “women are actually bad and not worth the effort so men should go their own way,” but in conversation with the larger plot and the hell Buddy goes through, I think it’s something else. Instead, LISA asks men to take women off the pedestal and treat them like human beings – people who always have personal agency and individuality, who are idiosyncratic, sometimes flawed, other times great human beings, wrinkles and all. Just as Nern and Rick need meaningful connections, romantic or platonic, women deserve not to be treated as objects that represent status and victory. And it’s only in this understanding that men can escape loneliness, and women can escape oppression.

In a patriarchal world, men feel marriage is their only path to success, happiness, and emotional well-being. Meanwhile, this is a lesson many women have gradually unlearned thanks to feminism, but men to this day are stuck in that traditionalist mindset. So they settle, find that their wives aren’t compatible, and fail to measure up to their impossible expectations of the ideal trophy wife, or they never marry and are taught that they’re losers who should hate themselves for “failing” in life. It’s not surprising that so many men are very competitive and very lonely.

That’s what makes LISA’s ending so tragic. Instead of presenting a solution, the game’s climax presents the sad reality of masculinity in a harsh, memorable way. Ultimately failing to discover expressive masculinity, Brad fights and kills his best friends from Birdy to Olan to even Terry, who realizes the hero of the story is an active threat to humanity and fight back, in his goal of reuniting with a girl who wants nothing to do with him. Brad presses on, mowing down Rando’s army, and approaches Buddy. He’s armless, depending on the choices the player made, and covered in blood and arrows. There are swords in his back.

“Why weren’t you there when I needed you! You’ve taken everything away from me!” Buddy exclaims. “I know,” Brad responds. Buddy: “Why did you do this to me?” And for the first time in his life, Brad finds some sort of bittersweet clarity. “I know you hate me…” but “for good or for evil… It didn’t matter, those men wanted to use you. For once … I wanted to do something good.” And, he’s right. Buddy has no agency in a man’s world. Buddy responds, “You can’t just be a father all of a sudden” and “You’ve hurt me the most.” And, she’s right.

A broken man who never got to live, victimized by toxic masculinity yet complicit in the vicious cycle, stands in front of a broken girl, acknowledges his faults, and asks to be held before he dies. A girl faces the worst of patriarchy head-on, and yet it’s also intersectional. At the origin point, both are victims of institutional masculinity.

Buddy has a choice, to “hug Brad” or to “leave him alone," but choosing either option feels unsatisfying. Even if you, the player, can make the choice, this isn’t agency, it's denial. Neither choice addresses Brad’s complexity, and neither gives justice or peace to Buddy. So, what do you choose? Do you embrace Brad, recognizing shared patriarchal trauma but ignoring his wrongdoings, or leave him alone, too angry about his mistakes to see the lonely, dying man in front of you who at least meant well in a world of toxic influences? A third option – taking Buddy off the pedestal, treating her better in the first place, finding comfort in meaningful companionships with other men – has long since become unattainable for Brad. The world of Olathe reached the final critical mass of toxic masculinity. It’s too far gone, too broken for change. In the end, Buddy’s gesture signifies the impossible fantasy of uncoerced human connection between the last living woman and a dying man.

But for us, maybe it’s not too late.