Is Life Truly Worth Fighting For?

'Endwalker' dives into the philosophical boundaries of JRPG’s greatest trope

At some point during the JRPG you’re playing, a character is going to make an impassioned play for all of existence. They are going to turn to the beleaguered protagonist (or, in some games, the protagonist is the one making the speech) and tell you — the player — that all of this is worth fighting for. That despite the things that have happened (and they have been terrible), there’s reason to continue on.

We’ve all encountered the enduring Power of Friendship trope at least once. It’s cute, endearing, and on the nose. It’s a standard and far-reaching story beat that is often the narrative lynchpin of the RPG, whether the game is as philosophically aggrandizing as Final Fantasy XIV or as charming and easy-going as Paper Mario.

The gist is that no matter what force brings itself to bear against you and your scrappy party of rebellious heroes, there is no power in all the universe (and beyond) that can stop the intangible love that you and your comrades carry for one another. The power of friendship — regardless of game, story beat, power structure, or narrative device — always wins.

Walking Toward The End

Three-quarters of the way through the Endwalker Main Story Quest (MSQ), a character that you’ve been waiting to meet since A Realm Reborn asks: “Has your journey been good? Has it been worthwhile?”

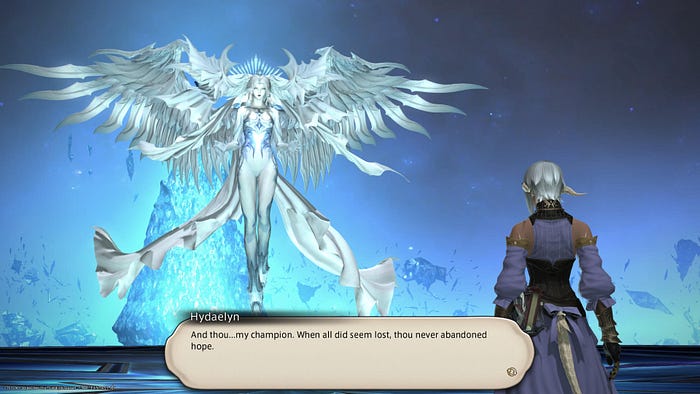

I paused. Endwalker takes players through a rollercoaster of emotions. Before this encounter even takes place, the game has exposed players to the aftermath of loss, suicide, apocalyptic happenings, broken families, and listless heroes alongside side-clutching humor and consistently bizarre Final Fantasy levity. It didn’t prepare me for the earnestness of the question. Nor did it prepare me as the character’s face fills the scene, ice-blue eyes piercing my soul with the weight of such a simple question.

The world — our world — is in a hard place right now. There is a dartboard of misery that is floating in the ether at all times, and whether by purpose or incident you will hit something on the mark, and it will alter the course of your life forever.

The pandemic, despite its combined severity and ludicrousness, is a fixture of life entering its third year of cooperative existence. I am an exceedingly poor individual, and my loved ones are likewise without money or means, and this makes life in the richest country on Earth both brutal and taxing. When asked to have simple empathy and care for our fellow humans, it can feel like a monumental request. The world seems slanted toward chaos in a near-Seinfeldian level of absurd cartoonishness.

While suffering is prolonged, growing, and inescapable just outside my window, Endwalker dives headlong into the philosophical boundaries governing the greatest of all JRPG tropes: is life truly worth fighting for?

Falling For Despair

I have a deep love of fiction that crosses the boundaries of reality. As a writer, my beliefs on the page are not always shared by my feral meat anchor, though my basest self crosses over at the most important points. In person — and ever online — I often come across as cynical, brash, and resolute. On paper, I am a devout humanist and pacifist, a genuine believer in the singular will of earnest humans and the indefatigable capacity to do good in the face of overwhelming evil.

I blame JRPGs for cursing me with this incurable optimism.

Like many devout Final Fantasy fans, the series long enraptured me before I was an adult. During the time between A Realm Reborn and Endwalker, there has been an absurd period of growth, change, and acceptance. I was in my mid-twenties during the launch of A Realm Reborn and now I am facing my mid-thirties, Endwalker barely two days finished. The game has made me tender, hopeful, resolute, and indulgent. Most of all, it has only burnished my belief in the prevailing good to a glossy sheen.

Endwalker is, at its core, about philosophical nihilism. Faced with the threat of apocalypse early in the campaign, the narrative sets itself up in the second half to make enormous and sweeping gestures about the meaning of life and whether the effort of living is worth the price of inevitable death.

This is a road that JRPGs have trod down repeatedly with mixed results. The power of Endwalker is what is behind it, over eight years of stories and characters chained together with serialized ambition that puts the Marvel Cinematic Universe to rightful shame.

The nihilism discussed and enacted in Endwalker is built around a simple axle: at this three-quarters point, a newly introduced character with universal properties and a dividable consciousness takes to the stars and returns with the unfortunate news that the universe is not ending, but in many places has already ended.

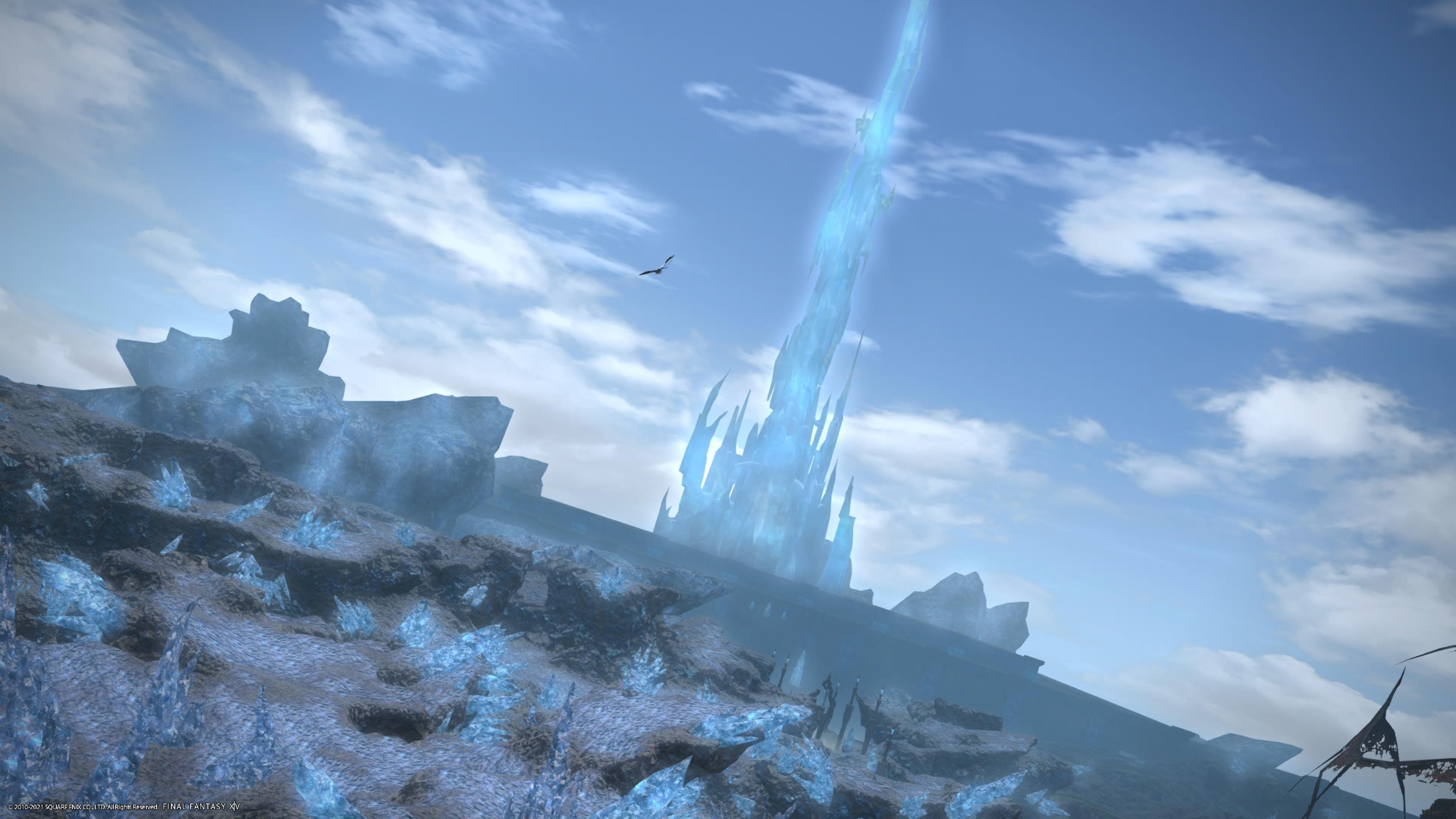

Sent far beyond the world of Eorzea (known also as Etheirys), Meteion returns with grave and robotic news: famine, warfare, apocalypse, and death have razed every single world she found beyond our own. We see the truth of this with our own eyes before the curtain of the last act falls. It’s incontestable proof that the universe not only houses other civilizations, but that these civilizations have been brought to a terrifyingly low point. In some places, the news is even more chilling. Some of these discovered planets and stars have brought upon their end on their own terms.

Meteion — then convinced that there is but one answer in the universe — attains her truth through a protected nihilism that decides that the only way to avoid misery and suffering is to bring an immediate end to all things.

Hydaelyn — also Venat, also the Source, also your Great Reason — runs the campaign against Meteion’s selfish and simplistic nihilism, responding in kind that suffering is life’s reason, that without it there can be no authentic way to track worth. This is the great philosophy of Final Fantasy that has been stewing for thirty years: good things are ultimately worth fighting for.

You Are Not Alone

This is the mighty through-line of Endwalker, though it can better be said that this is the binding agent of all great JRPGs and significant stories: you are not alone. A mantra repeated throughout the MSQ, this is yet another throwback to a titan of an RPG, Final Fantasy IX. In it, as a song plays of similar title, the game forces the hero Zidane to confront the truth of his existence as his heroic friends fight at his side, throwing themselves in harm’s way as he struggles with a crippling bout of existential dread.

It’s easy enough for us to fight for our friends — the power of friendship begins and ends there, of course. Endwalker, however, asks the tougher question: do you fight for everyone, or just who you care about?

JRPGs have asked this question for years, as you often play as a group of rebellious youngsters traveling the world and sacrificing time and body to bring down some nefarious imperial system or great deific evil. Endwalker takes this globe-trotting planet-saving effort steps further by showing you behind enemy lines firsthand.

The game forces the party to spend some time with their enemies in Garlemald before moving on to confront their cartoon villain on the moon. It’s easy enough to cast an entire race as evil in fiction, but Final Fantasy XIV is not content with this, instead showing the Scions of the Seventh Dawn putting themselves in harm’s way for those who have been their sworn enemies for years. While it may be satisfying to brutalize villains with sword and spell, Final Fantasy XIV is no stranger to showing the Hero of Light taking former enemies under their wing and growing a vast, tightly bonded militia of comrades.

With former enemies on our side — Imperials, Ascians, and Primals — there is one question left for Final Fantasy XIV to ask, which is: does any of this truly mean anything? As we prepare for the last battle with Meteion on the literal edge of the universe, Endwalker makes itself more philosophical than any Final Fantasy before it, lathering our existentialism and anxiety with exposition after exposition that challenges the very bedrock of purpose. Is there actually any point to life at all, and if there isn’t, what do you do?

The Final Days

The fault found in philosophical nihilism by most is that it lacks choice. Regardless of what philosophy or religion you subscribe to, there is no meaning in the void of space. Things live, grow, wilt and die at their own pace and structure, and many things exist beyond our understanding. What is left to us as conscious beings is to assign purpose to our own lives, to chart a course through the unknown by deciding what has meaning and value. There is no greater direction than to give value to every life around us, to fight tooth and nail for the right to live and be happy. The Scions in Endwalker resist Meteion on this exact premise, showing her that the meaning in life is that there isn’t one, that by getting to choose what we do, we assign value to our hopelessly small and stinted experiences.

Like Seymour, Necron, Ultimecia, or the many Final Fantasy villains before her, Meteion’s premise is flawed because it is a truth held against the will of others. Whether Meteion has discovered irrefutable proof that there is no purpose to prolong existence, she has no right to make that choice against the free wills of people who want nothing more than to make that discovery on their own.

Whether you’re a grand hero saving all the peoples of Eorzea or a simple secretary hoping to become a mighty artisan, the meaning in your life is assigned by you and you alone. Therefore, it cannot be taken away or blunted by someone outside your consciousness. Hydaelyn was correct when she fought against the Ascians and Zodiark for the planet to live because she saw the cowardice in oblivion. Suffering hurts — and most of us would do anything in our power to prevent our loved ones from feeling pain — but not a single one of us has the right to divine the path of another just because of our personal points of view.

Endwalker posits that life is worth fighting for because everyone has the right to decide who they want to be and what they want to do.

“Has your journey been good? Has it been worthwhile?”

How would you ever know, if you are not granted the chance to experience it?

Close In The Distance

In February of 1998, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science proved that human observation affects reality. While doing the experiment, these researchers wanted to prove that the state of waves and particles differ when placed under human scrutiny. A property called interference occurs only when no one is watching the particles interact, and “when under observation, electrons are being “forced” to behave like particles and not like waves.” Quantum mechanics has long proved that the very observation of conscious beings can alter reality on a subatomic level, that the “observer effect” can disturb any system by the mere fact of observation.

Meteion — in her observance of the death, cruelty, barbarism, and apocalypse that exists within conscious cultures — became an unwitting member of that same system. When her shared consciousnesses united in their appreciation that all life must eventually end, they overtook her kind and inquisitive self to create the song of oblivion. The nihilism that Meteion’s supposed neutral truth is steeped in is unequivocally flawed. Once she observes the endless suffering created in cycles throughout the universe, that suffering observes her back. If you gaze long into the abyss, et cetera.

Conscious creatures, despite their best efforts, do not operate solely on logic. They are woefully turned by fear, pain, suffering, and hatred. The JRPG logic is to resist these things and keep fighting, because motivation and effort are always correct because the logic of the game dictates that we never stop moving forward. Endwalker, in its wisdom, gives us a philosophy to chew on long after the final credits roll.