How Video Games Use Reduced Stimulation

Varying stimulation can dramatically alter game experiences

A grenade explodes nearby (well, in the game you’re playing), sucking away all the sounds of the battlefield and filling your ears with a dull, manic ringing. You’re relieved when the aural effects of the grenade fade, allowing you to hear enemy shouts and gunfire as you scramble for cover. You now appreciate what you had before because it was momentarily taken away.

Let’s talk about reduced stimulation in video games.

All about affordance

Game design, just like any other type of design, is predicated upon a strong relationship among affordances, signifiers, and feedback. While these are common terms in design-speak, I’ll establish a working definition of how I understand them below. Bear with me, because this is relevant to how reduced stimulation is used in games.

Affordance: The possible ways (real and perceived) in which any object can be used. Affordances stem from an object’s inherent design and our own biases while interacting with similar objects in the past. A sidewalk presents the affordance of walking, standing, running, and more. To take a more video game example, a lever next to a door presents the affordance of being pulled and having an effect on the door.

Signifier: Clues that enhance the affordances (or invalidate certain perceived affordances) of objects. It’s a designer’s job to place signifiers and minimize the distance between truth and perception for users. A ‘No Running’ sign on the sidewalk is a signifier that the sidewalk isn’t meant for running. A ‘Pull Me’ sign or blinking lights near the lever are signifiers that validate your initial assumption about the lever.

Feedback: Reinforcement that you’ve used the object in the way it was meant to (or haven’t). Designers must account for consistent feedback so that users know they’re progressing in their journey. A fine for running on the sidewalk with the ‘No Running’ sign is feedback. A red glow and a closed door changing to a green glow and an open door when you pull the lever is feedback.

Video games function by guiding and teaching you to interact with the game world and objects as intended (through signifiers) and telling you when you get it right (through feedback). This is done through visual, audio, and mechanical clues. Essentially, stimulation.

It’s interesting when games break from this convention and reduce stimulation to provide greater challenges, unique atmosphere, and more.

Let’s see some ways in which games do this.

Increased challenge

Powerful enemies, tricky platforming, brain-busting puzzles, or anything else that demands precision and skill are conventional methods to increase challenge. A lesser used trope is reducing stimulation and forcing you to adapt without the help of the usual signifiers and feedback to oversee your path.

Shovel Knight, an indie platformer, does this well in its Lich Yard level. This is how the level looks at the beginning:

You’re comfortable with how the game works, the character moves, and the enemies attack. Visual and audio clues are present. The level might be challenging, but the stimulation isn’t tweaked.

Then this happens:

You have to deal with the level in pitch darkness, committing the world around you to memory as staccato lightning briefly illuminates the land.

Jumping across platforms changes from perfunctory to treacherous.

Enemies hide in the blackness, begging to be overlooked.

It feels like playing a completely different level, even though it’s not. It’s the video game equivalent of moving around the house with a blindfold and a flashlight.

It’s important that the game doesn’t reduce stimulation to such an extent that it starts feeling unfair, however. And Shovel Knight doesn’t fall into that trap. New enemies and mechanics are always introduced in the light first. For example, you learn that you can shovel bushes into the air and use them as leverage for jumps at the beginning of the level.

Later on, you’re tasked with doing the same thing beneath an inky sky.

The Lich Yard level reduces stimulation to increase challenge but maintains a balance in doing so. You feel a loss of control but never a complete lack of control.

Increased replayability

Incentivizing players to go through game levels multiple times is almost always a good thing if done properly. It decreases game development costs as the same assets are used for multiple experiences. It increases the shelf life of the game. And it lets players measure their progress, marveling at how much they’ve improved since the first time they played a particular level.

Replayability is usually encouraged through hidden collectibles, secret areas, optional objectives, and time-limits. But I demonstrated in the previous section, reducing stimulation can effectively change a level and entice repeat playthroughs.

Rayman Legends, a zany Ubisoft collect-a-thon, employs this concept effectively. As end-game content, some Rayman levels have special ‘8-bit’ or low-res versions where the visibility is deliberately grainy and choppy, making the already precise platforming that much more difficult.

So, a level that looks like this…

…has an 8-bit version that looks like this…

The ‘8-bit’ level cannot be beaten without gaining mastery over the original level, knowing its every nook, cranny, beat, and jump. This encourages you to not just ‘pass’ every level, but gain an intimate understanding of its layout, your character’s jump-arcs and acceleration, and the exact enemy placements.

I mean, how else can you beat this?

Just like Shovel Knight, Rayman Legends isn’t unfair with its reduction of stimulation. You can beat the game without playing these ‘8-bit’ levels, so it’s end-game content meant specifically for completionists and advanced players. And while the ‘8-bit’ levels themselves might be merciless, you have a far more forgiving training ground to get your feet wet.

Engaging pacing

“There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it.”

Alfred Hitchcock

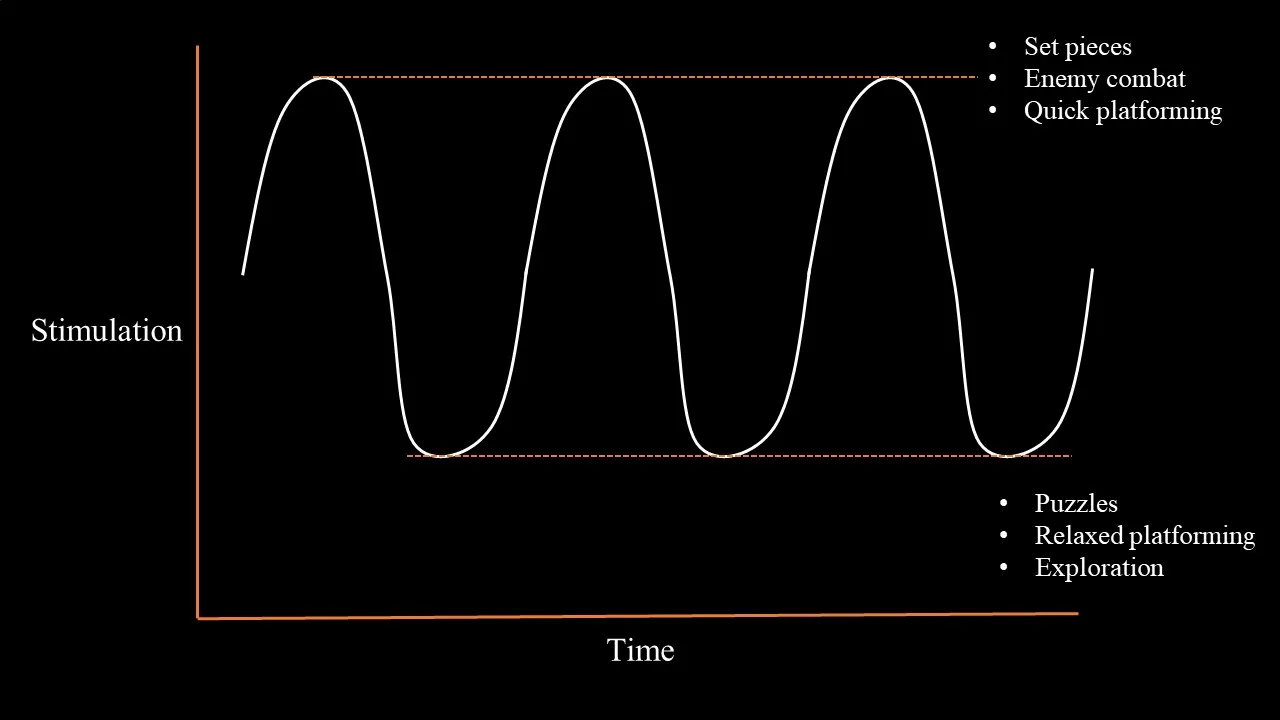

Apart from reducing stimulation in specific levels, games (especially story-based games) also dial-up and reduce stimulation periodically throughout their duration to keep the player engaged. If an action game, for example, is all high-octane payoff and no simmering build-up, it won’t hold the audience’s attention.

The changing stimulation we’re talking about here is not the sporadic darkness of Shovel Knight or the messy static of Rayman Legends. It’s more often the stimulation of game mechanics that are varied to change the pacing and give players different things to do.

Uncharted 2 is a great example of pacing done right in games. Each high in the story beat — whether it’s manic combat, speedy platforming, or bombastic set pieces — is bookended by the quieter lows of puzzle-solving or reflective exploration.

A sequence in the mid-point of the game follows this sine-curve perfectly. After protagonist Nathan Drake hitches a ride on a train, you fight your way through bogeys full of armored enemies, hanging off the edges, dodging railway traffic signs, and even bringing down a helicopter.

After the train crashes in the snowy mountains, Nathan is rescued by a Tibetan Sherpa and brought to a village. The relaxed stroll you take through the village is an ideal juice cleanse to contrast with the previous bloodbath. The sprint button literally doesn’t work during this section. You’re implored to stop and smell the roses, so to speak.

Nathan then goes searching for secrets in the mountains with his new Sherpa friend. The stimulation ramps up slowly with some relatively easy platforming.

A mini-peak is reached when a horned, hirsute horror-monster jumps from the shadows and charges at you, breaking the tranquility.

Once you’ve taken care of the menacing monkey man, the stimulation cools down again with some calm but visually stunning puzzle solving and platforming.

You eventually escape the cavernous ice and get back to the village, only to find that the bad guys have attacked with all their might. This is where the stimulation mirrors its crescendo from the earlier train sequence as you engage in battle with enemy forces. And a tank.

Everything in Uncharted 2 is over the top. The peaks have helicopters and tanks and are really peak-y. The troughs have massive puzzles and beautiful exploration and are still really stimulating. But within this heightened visual framework, game mechanics are used as the stimulational fulcrum to create an engaging narrative see-saw.

Unique tone

Genres in media — whether it be movies, books, or video games — are pretty much set in stone. One of the ways to differentiate your creation is to adopt a unique tone within that genre, a mix-and-match combination of elements that separates your work from its run-of-the-mill counterparts. Deadpool and Captain America: Winter Soldier are both superhero movies but their tones couldn’t be more different.

One of the ways games can author a unique tone is (you’ve probably guessed this by now) by reducing stimulation and removing extraneous design elements to make players feel a particular way. For instance, Journey makes players feel a sense of smallness and wonder as they travel harsh lands at the mercy of fellow strangers by looking like this.

No enemies, combat, or dialogue. Just huge swathes of empty sand with a mountain simmering in the distance. Expansive, serene, and unmindful of your presence.

Moving from expansive to oppressive, games like Limbo and Inside are bleak, saturated in grey, and invoke shades of film noir in their presentation.

Why is the tone and atmosphere of these games unique? I think one reason is our brain’s proclivity for storytelling. For millennia, the brain has remembered and passed on things in story form. It craves narrative coherence. So, just like the brain fills in gaps to produce a picture from disparate shapes, it also fills in gaps in what we’re seeing to form a story (a special left-brain function called ‘The Interpreter’ does this).

So if a game deliberately has sparse visuals, non-verbal narrative, and layers of abstraction — reduced stimulation — we fill in the gaps. And each of us might fill in those gaps differently. If Uncharted 2 is Nathan Drake’s story, Journey is closer to our own story.

Can you think of any other interesting applications of reduced stimulation in video games? Let me know in the comments! Thank you for reading.

Also, check out this video by Daryl Talks Games for more neat stuff about how stimulation helps make games memorable.