How Punk Culture Influenced Gaming

The intersection of punk and digital entertainment

It's 1999. You're at Pizza Hut. There's a dim, waxy florescence to the dining area and all you can smell is the greasy cheese of baked pies. You see tables spotted with the iconic red cups and look up at the stained-glass Pizza Hut light hanging overhead while in the background, faint but melancholic, Johnny Rzeznik croons "Slide" to you. But you're here for more than pizza and ambiance: you're here for the demo discs. For the brief chance to play through Crash Bandicoot, Tony Hawk Pro Skater, Final Fantasy VII, and Spyro before their actual Sony console debuts. After the meal you're slipped a disc, the employee sharing an affable wink of understanding, and you, wide-eyed, clutch it with eager anticipation as your parents across the way fuss with their coats. It's a fair exchange that's almost too easy. Free games? With a pizza?

Okay, so I'm not really sure how it all went down. I'm from the US state of New Jersey, central Jersey, thank you – mecca of American-Italian pizzerias (although I'll give this to you, Chicago, technically you guys had the first pizzeria), able to easily swap between New York City and Philadelphia foodie scenes. I grew up on the tradition of pizza. We never went to Pizza Hut.

I mean, no offense to Pizza Hut. Actually, scratch that, full offense to Pizza Hut (for the sake of this piece at least – really, you guys are okay). This article's about the punkification of video games. It's about the counterculture that inspired the North American video game scene and how the youth of the mid-late 90s and early aughts shaped gaming and how gaming shaped them. It's supposed to be transgressive. It's supposed to stick to the man. It's something unpredictable but in the end, it's right.

The Evolution of Punk

"Punk rock, when it arrived, was edgy, brief and unpolished, with unpredictable and chaotic live performances which sometimes ignited pent-up crowds into violence. Out went virtuoso solos and twinkly stagecraft: musicianship came second to attitude, and the feeling of accessibility – that those on stage weren't couched and pampered rock stars, but just someone with struggles, frustrations and something to say. Lyrics were often politicised or critical of what was increasingly seen as a country run by arcane and regressive institutions."

What was punk - and why did it scare people so much? by Simon Ingram

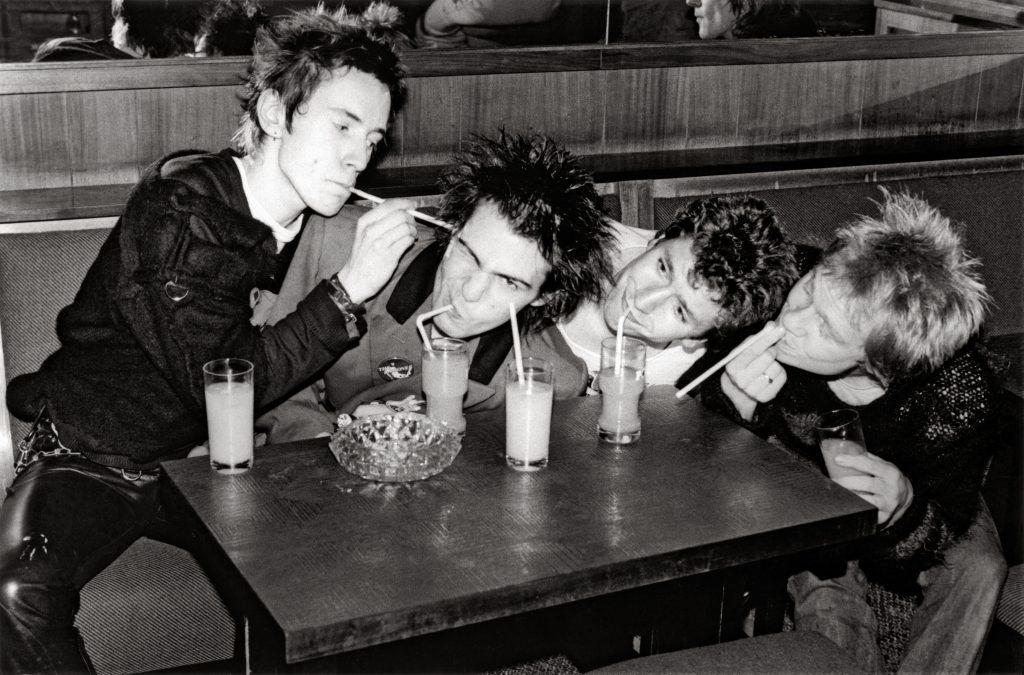

The image of the traditional punk rocker – ripped jeans, leather jacket, shades, cigarette hanging limply out of the corner of their mouth – originated in the UK, during a time of economic downturn and general restlessness with the state of the nation. The musicality stirred a passion for rebellion, fostering anger in a way that was productive and, at times, regressive. It was anti-everything and it ignited the rock music scene.

Punk was seeing similar success across the Pond, with punk acts taking off on the heels of the popularity of the Sex Pistols and The Clash. In the late 80s and early 90s, new acts like Nirvana further progressed the musical revolution in a grungier direction while maintaining its revolutionary roots. This all culminated in a musical nexus in the 90s that saw punk, grunge, and the underbelly of the music's rock world go big. Acts like Green Day, The Offspring, and Sum 41 formed an ambiance of rock-punk iterations, each with their own stylistic interpretations of the genre's ambassadors. Punk was rather exclusively underground until the early 2000s, and its emergence to the mainstream came with its own sort of growing pains, but its development alongside other cultural movements - like skateboarding - created an even more diverse sound of rebellion.

Punk began to seep into another type of media that was also beginning to emerge from the infancy of its own creation at the time – video games. After emerging from the near-apocalyptic crash of the market in the mid-80s, games were still largely relegated to the arcade and underpowered handheld devices. But after the runaway success of the NES in the latter half of the 80s, game makers were growing confident in their new lease on the market through the home console system now at the cross-section of its fourth and fifth generations, also known by their various alternative names based on the processing power of their CPU (the 16-bit and 32-bit/64-bit respectively).

The Sega Genesis, SNES, PlayStation, and Nintendo 64 all circled around each other during the century's last decade. Experimental developers adapted their games to the current market and all the rapidly changing development tools emerging at the time. And the current market was seeing waves of punk-inspired adolescence born of the US-suburban dystopia – a hell of manicured lawns mimicking the perfect simplicity of past generations and bursting at the seams with angst.

It's All in the Cart

Emerging from the niche and more community-rich arcade era of gaming, the mid-late 90s and early aughts saw its opportunity in the residue of the punk-fueled underground alt-scene, which formed the background noise of a restless pre- and post-9/11 youth. These two versions of America were separated by a distinct fissure. The later 80s and early 90s saw a melding of punk culture with a chill, stoner sublimity, echoed aptly in the popularity of reggae-punk's Sublime. But the alt-underground scene was far more prescient, with the emergence of blink-182 and Jimmy Eat World's amateur debut albums near the middle mark of the decade offering a glimpse of the soundscape of the future.

1994's Skitchin' for the Sega Genesis (a game my partner actually told me about, which fit perfectly here!) carried these early vibes to the digital world. Electronic Arts' extreme rollerblade offering followed in the steps of their previous game, Road Rash, as a racing melee that involved knocking opponents off their rollerblades with various weapons and pushing them into oncoming traffic, all while trying to hitch a ride on passing cars.

Skitchin' was created using rotoscoping, employing the help of real rollerbladers to digitize the sport and give players a more realistic experience. It was produced by their Canadian studio, whose members drove around Toronto to study the skater/blader scene. They eventually built a warehouse with ramps, caught the coolest moves they could on camera (performed by an in-house member), and then worked to translate them into the game. GamePro interviewed the producer, Stan Chow, in their March 1994 issue:

Stan: We took them [graffiti artists] to the EAC offices and showed them the young people working there. They thought the whole idea was the coolest thing. They even suggested we use grunge music in the cart.

GP [GamePro]: There are about 15 tracks in the cart. How'd you lay down the tracks?

Stan: It was a great idea, but our staff musician wasn't into grunge. We had to lock him in a room with a bunch of CDs of bands from the Seattle grunge scene. Slowly he caught on, so we let him out of the room.

GP: Any aftereffects?

Stan: He digs grunge now!

Skitchin's development process came from an organic understanding of the scene at the time. The artists they asked to design the graffiti in the game came from a phone number written beside a particular piece of street art, which lead them to a small group of teenage artists who they'd eventually commission for the game. And although rollerblading eventually ceded its crown to a different four-wheeled pastime, the core of the culture found there merely switched focus. In 2000, Activision released the sequel to a little skateboarding game that would go on to inspire a generation of young gamers – and become one of the most beloved titles of the early PlayStation era.

Halfpipe Hangtime

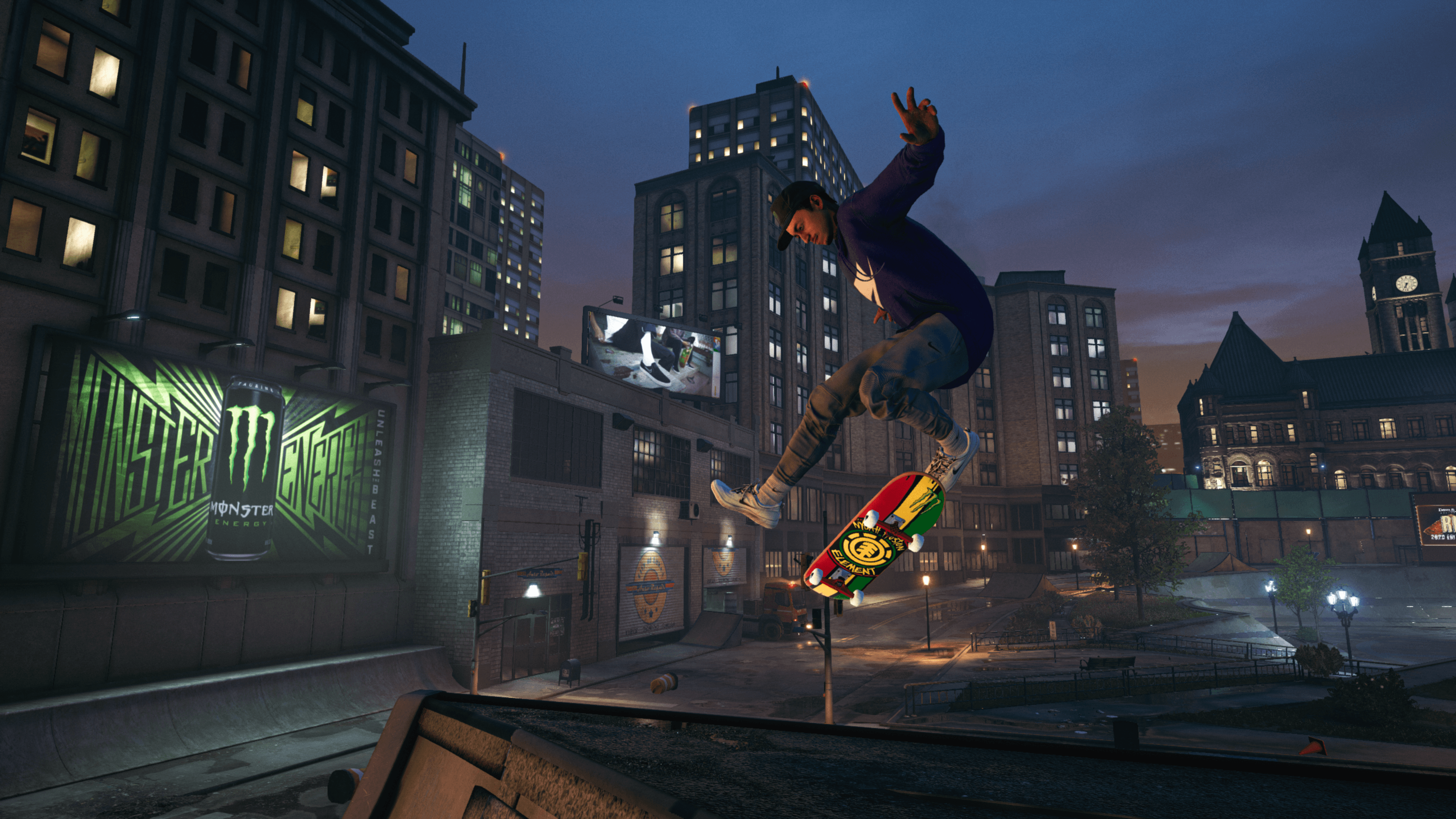

Neversoft Studio was a small California-based development team that, in the late 90s, had been tapped by Activision to work on an internal project called Apocalypse. They were also asked to design the prototype of a skateboarding game, which then went into full development after Apocalypse was released. That game would go on to become Tony Hawk's Pro Skater, the first in what would be a fairly long-standing franchise, with the help of legendary skateboarder and then-GOAT of the scene, (I mean...he still is), the eponymous Tony Hawk.

“In the past, I was very involved because I had to give the developers a crash course in skateboarding and skateboard culture and tricks and everything else,” Hawk says. “So those first four years I was hands-on the whole time."

Tony Hawk Still Embodies Skateboard Culture, From ‘Pro Skater 1+2’ To Everyday Life by Chris Barnewell

Tony's Hawk's Pro Skater would be released to critical acclaim, and Neversoft would follow up production with Pro Skater 2. This was a direct sequel that improved upon the first and brought to the forefront a convergence of musical brilliance in punk and hip-hop, combining the urbanity of the surf-punk skate scene with the more grassroots hip-hop scene that was musically radicalizing the youth of New York (and had been doing so for a long time).

Suffice it to say, punk and hip-hop were no strangers, and Pro Skater 2 made their link visible to an entirely new audience.

As Harold Hunter’s (the American professional skateboarder and actor who plays Harold in Kids) brother, Ron, explains: “It was like a puzzle that all came together… That’s how New York was. It didn’t matter where you came from, but if you fit into that puzzle you were good.”

A visual history of the moment skateboarding and hip-hop started to collide by Brooke McCord

The locales of Pro Skater 2 featured epicenters of skate culture that included NYC, as well as SoCal (southern California) and Philadelphia, among other stylistically radical areas (such as Skate Heaven, a location-undisclosed skate park in outer space). Pro Skater 1 and 2 proved massive hits (as did some of the other entries), but it was 2 that would carry the weight of the cultural legacy of the series. To this day the game retains a 98 Metacritic score and ranks regularly in various top-10 sports gaming lists (ranking at #9 for Bleacher Report). It remains a cultural cornerstone and tastemaker for the burgeoning pop-punk, ska, and hip-hop kids of the era.

Games like this sold us a blueprint of cool, of belonging to a community deemed important, that we spent hours trying to mirror in our own small lives. It's hard to replace that earnest, if naive, desire when you grow out of it. I try, all the time, to conjure what it feels like to listen to ska in 2001, with my brother on the tile floor my abuela warned would give us a cold, button-mashing combos programmed against failure.

The Music Of 'Tony Hawk's Pro Skater' And Its Emotional Legacy : NPR by Stephanie Fernandez

The Pro Skater series saw a revival in 2020 with the release of Pro Skater 1+2, developed by Vicarious Visions. The studio had obtained the original code for Pro Skater from Neversoft and used it as a basis for the remake, faithfully rendering the levels in the Unreal Engine 4. It added a variety of new features, new music, and new athletes to play as, highlighting the increasing diversity of the sport and its evolution into the modern era.

For a glimpse of the collection of its music, Spotify has the entirety of the Pro Skater 1 and 2 soundtracks in a comprehensive package that includes both the original and the remake. Whether you want to take a walk down memory lane or discover the classics you've been missing out on (as well as give newcomers to the movement a listen), it's a one-stop shop of punk-rock-hip-hop goodness.

The Kids Are Grown Up

Much like the skate and blader scenes' changes in modernity, punk would also undergo a critical shift in the early aughts, resulting in a scatter-shot of its culture and music that spread more distinctly into emo, pop-punk, ska, nu-metal, math rock (a recent favorite of mine), punk-rap, etc.

Its aesthetic would evolve with this divergence: the mohawk-punk rockers of the 1970s would give way to both the continuation of a robust classic trajectory and the emergence of a mainstream counterculture in the eyeliner of emo and pop-punk. Hip-hop inspired rock acts like Linkin Park were products of a post-9/11 world that grappled with very different questions in the face of a newly patriotic and destabilized America. This shift would also affect video game production, marketing, and censorship, marking a period of critical upheaval in the art of escapism and the reality of war, a topic I hope to explore more in-depth.

But the heart of punk's rebellious spirits siphoned the reclusive apathy of that era into something else, even if it was slightly uncertain and heady. 2005 saw the release of Guitar Hero, a more rock-than-punk-inspired game that put the guitar in the player's hands (literally) and would also go on to re-write how the music industry saw video games as a boon to sales and popularity. Neversoft even developed the later entries in Guitar Hero after the series was acquired by Activision in 2006, but would eventually merge with Infinity Ward to work on the Call of Duty series.

Guitar Hero would eventually give way to Rock Band. From there and into the early 2010s, gaming would explode in popularity as a mainstream pastime, while punk as we knew it then would fade into storied history. In 2014 Insomniac Games would take all things punk and throw them in a blender to create Sunset Overdrive, an apocalyptic beat-em-up that features all the hallmarks of an anti-capitalist analogy – even if it's through an energy drink conglomerate. Cyberpunk 2077 would further the punk aesthetic through the well-known lens of its namesake, although to touch on the myriad influences of punk on cyberpunk is an entirely different article.

We'll always have the memories of the youth-rich days, evocative of a summer spent in restless leisure playing Pizza Hut demo discs, of skate parks and fingers curled in devil horns, of spiked hair and the buzz of first tattoos; of the naivety of youth transforming into an acerbic realization of adulthood's white-collar horrors, fought against in screaming and shouting against the concrete walls and manicured lawns imprisoning punk's diaspora. To invoke Billie Joe Armstrong once more: for what it's worth, it was worth all the while.