Gunhead: Analyzing Design Choices in the Transition From 2D to 3D

A look into Gunhead's design using the MDA framework

Transitioning a game from 2D to 3D is a monumental task. When all of a game's systems have been finely tuned to serve a top-down or 2D-platformer perspective, how can developers be sure that those systems will remain fun in 3D?

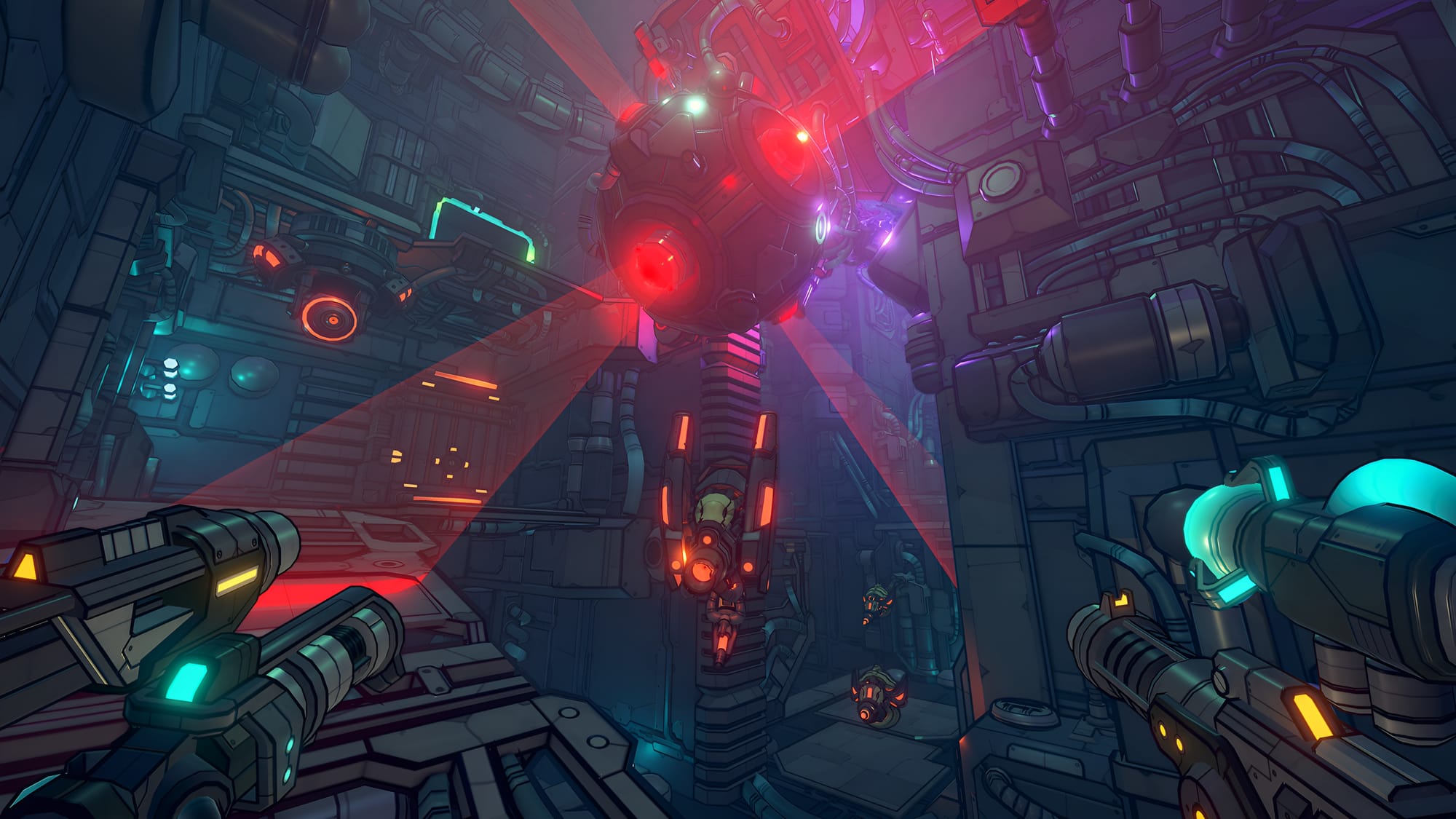

Although difficult, making this transition is far from impossible, as we've seen with the success of indie games like Risk of Rain 2, or even with AAA releases such as Metroid Prime. Gunhead, a new release by developer Alientrap, strives to revolutionize the top-down shooter gameplay of its prequel, Cryptark, by transforming it into an FPS.

Gunhead's roguelike progression incentives, bonus objectives, and interdependent ship defensive systems retain much of the charm that garnered a loyal player base for Cryptark. Its shift to 3D, however, brought many of Cryptark's game systems into a new context, which in many ways has led Gunhead astray from the strategic, action-packed experience that its developers intended to create.

In this story, I'll break down a few of Gunhead's core elements using the MDA framework to figure out why certain design decisions missed their mark. If you're unfamiliar with the MDA framework, it is a formal approach to analyzing game design that breaks down elements of gameplay experiences into 3 parts:

- Mechanics: how the game functions; the fundamental systems of the game

- Dynamics: how the player acts as a result of interacting with the mechanics

- Aesthetics: how the player feels when acting in this way

Table of Contents

First-Person Camera

[Mechanics] This mechanic relates to the player camera system and the verticality added through the 3D environment's additional axis. The field of view of the camera and its traditional first-person controls define how the player sees the game world.

[Dynamics] Players will move the camera to search for points of interest. Without the ability to gain an immediate grasp of all of their surroundings through a top-down view like in Cryptark, players will pan the camera around, following UI indicators on their HUD, to connect icons labeled on their 2D map to objects in 3D space, and to find enemies.

Players will first identify the position of elements along a horizontal plane using their map, then search for the unknown vertical position of the element using their camera. This becomes especially difficult with rooms that have multiple floors, as players will have to wander onto the correct floor before it even becomes possible to identify the object with their camera.

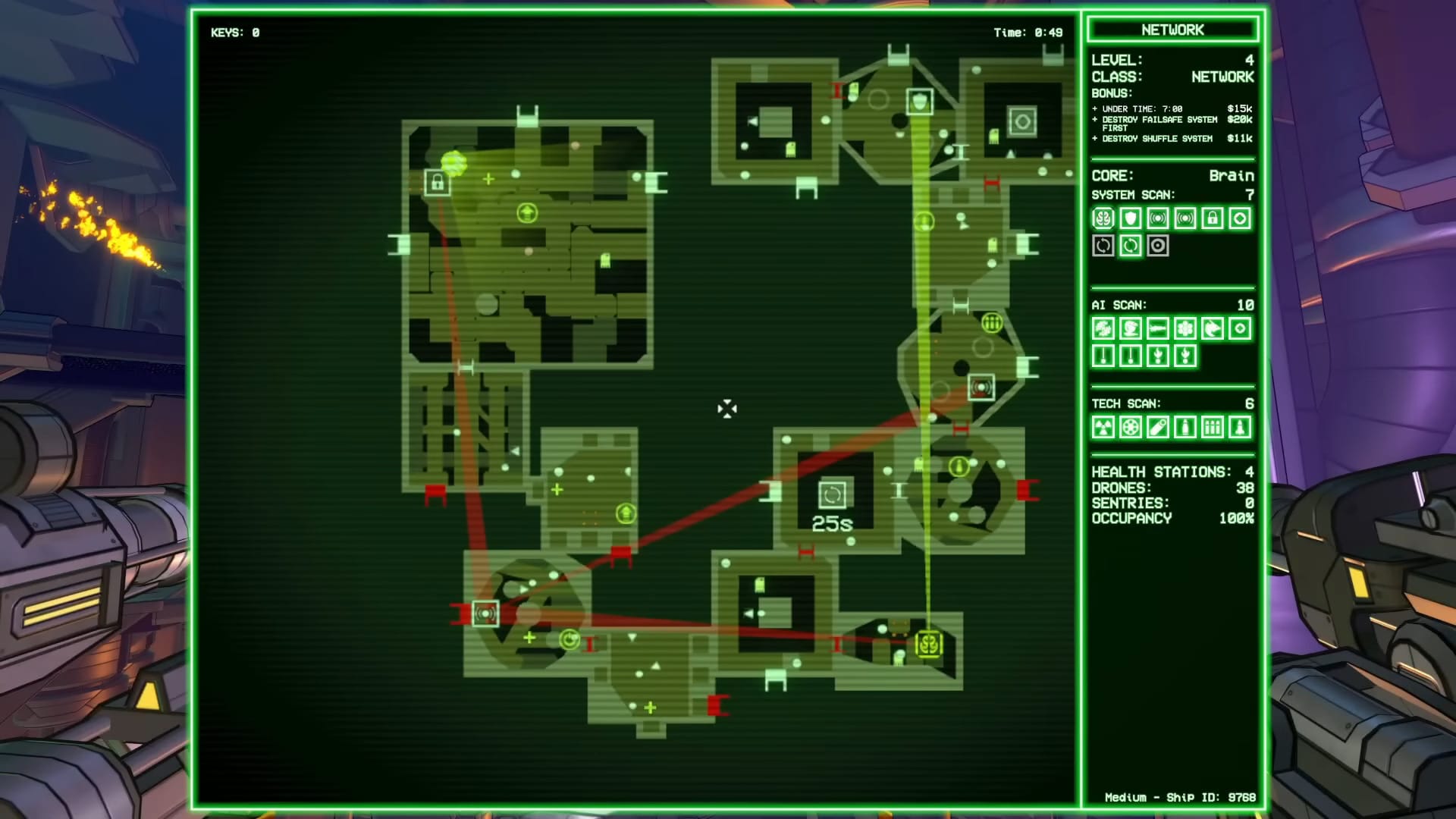

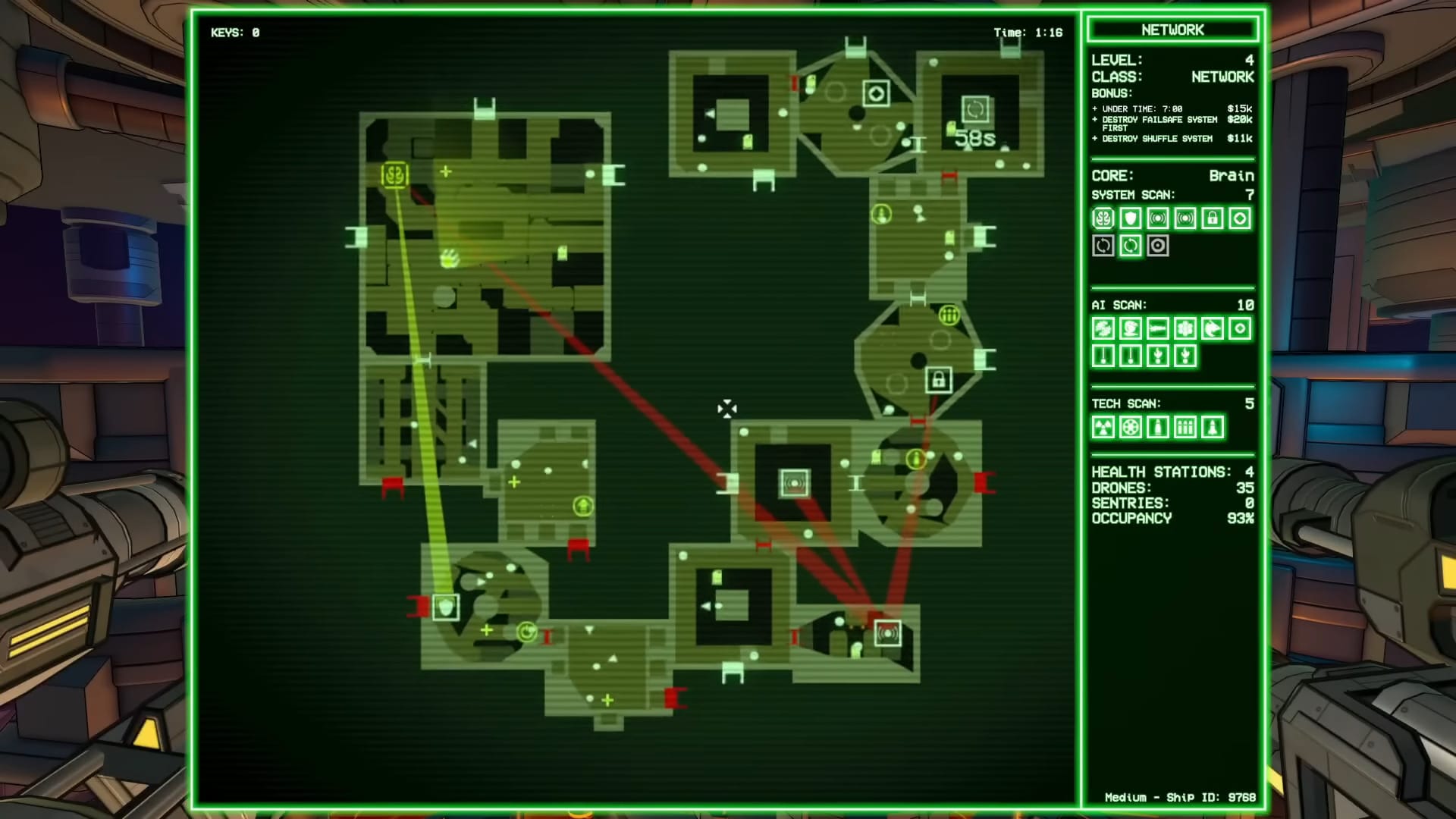

Top: Cryptark's map vs. in-game, Bottom: Gunhead's map vs. in-game, Source: Steam, Press Kit.

[Aesthetics] Although being able to view the world in more dimensions will make the player feel more immersed, it also creates many moments of frustration. This is because the dynamic of searching that this mechanic incites clashes with the game's values of being, in the developers' words, "strategic and fast-paced."

Gunhead's core gameplay loop consists of a cycle of creating a plan before boarding a ship and then executing that plan on a time limit after boarding. Forcing players to blindly search for where elements are vertically positioned interrupts the fast pace of execution by adding ambiguous time sinks based on luck. These uncertainties do not promote any strategic thinking and even worse, derail players' plans in a way that feels out of their control, leading to frustration. A better example of a mechanic that adds uncertainty to plans in a way that augments the game's core values is the shuffle system, more on that later.

Confined Level Design

[Mechanics] This mechanic refers to the cluttered or compact design of most rooms that are pieced together to create the ships that players board in Gunhead. The modularity of these rooms enables the game's procedural generation of levels.

Source: Press Kit.

[Dynamics] Players smoothly comprehend map layouts as a result of their intuitive modularity and formulate plans that are easy to recall by memorizing their steps as a sequence of rooms that they must visit. When in combat, players juggle focusing on an enemy to decide when to dodge alongside looking around at their environment to decide whether there is space for them to dodge.

To simultaneously attack while dodging enemy attacks, players will try to constantly stay on the move while maintaining focus on a target enemy. However, the many platforms and structures around them will often lead them to run into objects or make them restrict their own movement to avoid doing so, leaving them vulnerable, especially to enemies outside of their FOV.

An example of limited space leading to unexpected damage. Source: Wanderbots on YouTube.

[Aesthetics] Planning attacks and executing them is accessible and feels satisfying, but players feel helpless when taking damage in situations where their defensive options are limited by the space around them. This feels especially punishing as health can only be recovered through limited powerups or through spending significant funds.

Narrow spaces were not a problem for Cryptark's combat since players' top-down view made them constantly aware of everything around them. Although narrow spaces make strategizing more accessible in Gunhead, it makes many combat mishaps feel out of the player's control. This lack of control is exacerbated by the visual design of enemies which often blend into the environment.

Breathing room is essential for 3D games that involve many enemies because players will never be able to attend to all sources of danger at once. Risk of Rain 2's transition to 3D promotes this using big, procedurally generated levels, which allow players to dodge most attacks by staying on the move, as well as using a 3rd person POV which provides some visibility on enemies approaching from the sides or behind. Even when taking damage in situations that feel out of players' control, automatic health regeneration and a multitude of defensive items make the consequences feel temporary or less severe.

Shuffle System

[Mechanics] The shuffle system in Gunhead randomly rearranges the positions of systems on a ship, including itself, every 60 seconds. Powerups and items on the ship are unaffected. There can be multiple shuffle systems on a ship; if they are all destroyed by the player, the shuffling will stop.

[Dynamics] When a shuffle is about to happen (~10 seconds left) players will make a decision to engage in one of the following behaviors:

- if they are already attacking a system, they will continue attacking it to deal as much damage as possible or possibly even destroy it before the shuffle ensues.

- if they are in between objectives, they will either sit and wait or make use of the downtime by collecting powerups (nonessential to 100% mission completion) until the shuffle occurs, in order to determine what their next objective will change to.

Immediately after a shuffle, players will open their map to re-strategize and create a new plan, in the same way that they did before the beginning of the level. Players who feel impeded by the shuffling will, of course, prioritize and destroy the shuffle system first.

The shuffle system adds a finer level of strategy, as players will need to not only plan their approach for the whole level but also plan around what they can accomplish within 60-second time intervals. Players will have to make strategic decisions throughout a level rather than only at the beginning, promoting Gunhead's value of being strategic. Opening the map to re-strategize after a shuffle also pauses the timer, mitigating the consequences of a shuffle on a player's fast pace.

Before and after a shuffle. Source: Wanderbots on YouTube.

[Aesthetics] While re-strategizing doesn't impede fast-paced gameplay, an upcoming shuffle can, since 15 seconds, for example, isn't enough time for a player in between objectives to travel to a new system and destroy it. When forced to wait in these situations or stray from their plan and engage in nonessential tasks like collecting power-ups, players will feel frustrated. However; this frustration is much less than what is caused by the blind searching or unexpected sources of damage discussed previously, since the shuffle systems are made clear to the player at all times and are within their control to plan around.

Keeping the position of the shuffle systems themselves during a shuffle could mitigate this problem since players who feel frustrated will have an option to immediately eliminate the source of their frustration. This also adds strategic depth by giving players who struggle to plan around this mechanic the option of taking out shuffle systems midway through a level rather than only at the start, since they will always have an objective to move towards before a shuffle.

The dynamics here do create a positive aesthetic in the feeling of suspense, caused by the uncertainty of whether the player attacking a system will be able to finish destroying it in the time before a shuffle. This interaction creates a squeeze and release that makes accomplishing the goal feel much more satisfying.

Despite some of the shortcomings in the design choices made above, Gunhead still provides rewarding rogue-lite progression and gripping moment-to-moment gameplay when its pieces come together as intended. Let's take a look at a couple of features that hit their mark.

Auto-Reloading

[Mechanics] Gunhead features no manual reload; when weapons' clips are empty, they automatically enter a reload sequence that will restore the clip after a substantial period of time if reserve ammo is available.

[Dynamics] Without the ability to reload at will, players will inevitably find themselves running out of ammo with certain weapons in the midst of battle. With four weapons at their disposal, in these situations, they will switch to a different option for primary fire instead of waiting for their previous weapon to reload.

[Aesthetics] Players will feel tense as they are forced to make quick decisions as to which weapon to switch to once one runs out of ammo. They will feel powerful when their choices help them make it out of these tense moments and keep up the offense. Both of these aesthetics elevate Gunhead's strategic and fast-paced game pillars.

Bonus Objectives

[Mechanics] While missions in Gunhead only require the player to destroy the ship's core for completion, each mission features a set of bonus objectives that will further reward the player. These often involve a time limit, destroying or not destroying certain systems, or other restrictions such as not using health stations.

[Dynamics] Players will decide which bonus objectives they want to target before a level, and at times adjust this list depending on how easy or difficult pursuing them is during the level. Players will experience various playstyles depending on what bonus objectives they choose to follow, such as speed running when under short time constraints or moving more cautiously when trying to keep the alarm system intact.

[Aesthetics] The bonus objective system gives players fine control over Gunhead's difficulty, allowing them to adjust it for each level or even throughout an individual level. This allows less-skilled players to progress and feel accomplished while providing veteran players with a rewarding challenge.

Taken all together, Gunhead is a solid rogue-lite with a polished visual style. Although its FPS gameplay is engaging, the way players interact with certain systems takes away from the strategic and fast-paced experience it intends to create. There's much more to be explored about the game that was not discussed in this story, but as a whole, Gunhead seems to serve more as a great change of pace for fans of Cryptark rather than an enhanced sequel to it.