Gacha Games: A Discussion

What is the present, and future, of gacha?

I may be one of the few people who spend their days checking out and covering the hottest and most original indie games (usually on Steam or itch.io), only to then go and play mobile games like Arknights or Limbus Company. I find there is a widespread perception that mobile games reached their peak with Candy Crush or Angry Birds; that is to say, there's often an ignorance - even among gamers - about the breadth and depth of mobile games on offer.

In reality, the mobile gaming market experienced significant growth and transformation over recent years, starting around 2017. The big change was that mobile games started to offer what we might typically recognize as AAA-rivalling experiences (games with impressive visuals and immersive gameplay). Chinese publisher/developer miHoYo - which was once an unknown entity - is now a powerhouse that finds itself being compared to the likes of Valve or Blizzard, thanks to the incredible success of its games. But there's a catch here; no matter how large or financially successful they become, there's always a gacha-shaped elephant in the room. This relates specifically to the monetization strategy underpinning their games. It's a strategy that is often considered unethical and this, in turn, can make it difficult to assess and discuss their efforts. Let's examine this more closely.

Mobile gaming and gacha

The gacha-based market (along with the mobile market) expanded rapidly in the 2010s. Yearly ESA surveys indicate that mobile is the most-played platform by a large margin across all games. In its infancy, mobile gaming was often stereotyped as being only relevant for highly casual players who wouldn't typically be viewed as "gamers" (e.g. bored parents or grandparents who want to fiddle with their phone for a few spare minutes between other tasks). And, to some degree, the predominant mobile gaming experiences available at that time only served to support this stereotype. Today, however, mobile games can be highly elaborate affairs featuring impressive stories, beautiful graphics, and deep gameplay systems.

It's not just that mobile games (and perhaps the players) have changed over time. Mobile games have profoundly influenced the way many people think about the overall value proposition of games; in other words, a whole generation of gamers has grown up with the expectation that games should either be free or involve a trivial financial cost to access. The caveat here is that even "free" games are usually not so; developers have, over time, crafted increasingly novel methods to monetize these experiences. I'm happy to admit that I've spent money on a few mobile games (like the aforementioned Arknights and Limbus Company). Having said that, it's not at all uncommon to encounter players who have sunk many hundreds of dollars into their favorite game.

There's something of a recursive cycle going on here, too. It is increasingly the case that developers release a game and support it with continual updates for many years post-launch (at both the speed and volume that was perhaps never imagined in the past). But this support doesn't come cheaply, and requires that said game generates massive recurring income throughout its life. Many gamers have become cynical about this cycle, especially the constant and persistent attempts by developers to dip into their bank accounts over and over again. And yet - despite these complaints - games built on this model continue to flourish. Diablo Immortal is a great example of a game that was poorly received by hardcore players right from the beginning. Despite this, it's still made more than $500 million and counting, which is a huge achievement by any measure.

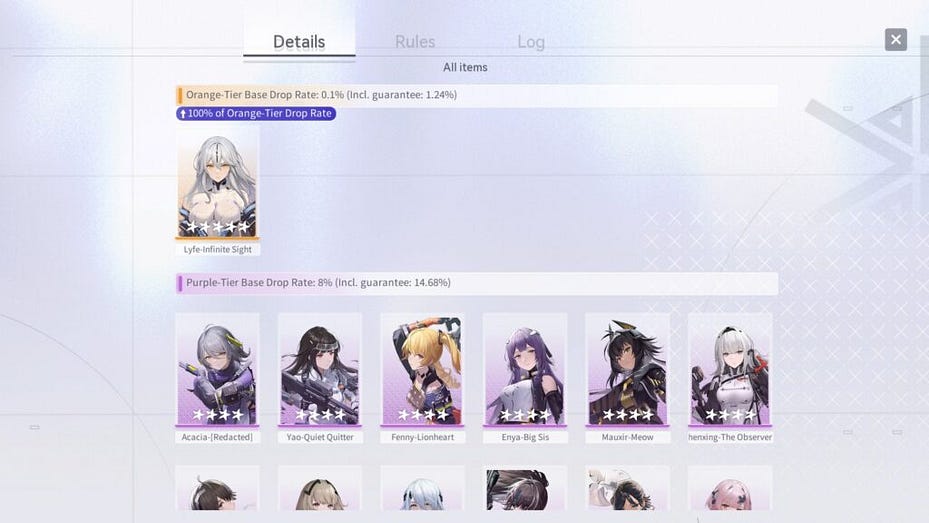

So, how have developers managed to wring so much money out of their games over a period of time? There are numerous methods, but one of the most common is known as gacha. Gacha - the term I'll be using throughout this story - is the shortened form of gachapon (ガチャ ゲーム). Gachapon machines are extremely common in Japan, and their mechanics are simple but effective: you pay some nominal amount of money and receive an item in exchange. Gachapon machines usually contain some finite set of items (for example, twelve different types of Pokemon figures). The trick is that you never know precisely which item you'll receive. This means there's a chance aspect to the experience, which is often compared to gambling. Video games - particularly mobile games - have implemented a range of systems over the years that roughly align, in one form or another, to this gacha-style concept. Players might receive a random item, or a random character, or something along those lines. Again, comparisons have been made to gambling, because players are being asked to use real money to acquire chance-based in-game items.

"But there's a catch here; no matter how large or financially successful they become, there's always a gacha-shaped elephant in the room."

Monetization maladies

Let's now consider some of the arguments surrounding gacha mechanics. I want to do this by establishing some of the common defenses of the practice in order to examine them more closely.

An initial argument in support of gacha - or at least, one that suggests it is at least a non-issue - is that these mechanics are typically optional. That is, you don't need to spend money to enjoy these games. Let's remember, though, that the purpose of gacha design is to generate player FOMO (fear of missing out). Acquiring the new six-star character might be essential for your team (while not doing so might lead to account ruin). Of course, there will always be people who play these games using nothing but the free characters. But if you want to experience all these games have to offer - really, arguably, to play them as intended - you'll want to seek out those six stars.

It's not just that FOMO is involved. It's that this FOMO is one component of a mutually-buttressed system that deliberately incorporates friction for players. Every gacha game I've played - whether intentionally or not - includes inherent pain points (such as sharp difficultly spikes) that create barriers for new players who aren't yet powered up. Limbus Company, for example, includes one of these friction points right at the beginning of the game. I now have access to every single piece of content in the game (and I've spent about $40 for the different season passes), but this has involved a very large time investment. There are some battles within the game that I can't imagine a new (or simply unlucky) account ever having the means to win. Arknights can also be painful in some of its early chapters. I remember hitting brick walls in Chapters 5 and 6 because I lacked a good ranged character or a six-star to help me overcome them. A defender of these systems might say something like, "you can add friends and request a character" (these are features many similar games have), but I find myself frustrated by such features: they are Band-Aid fixes that paper over the inherent difficulty spike problems.

"It's not just that FOMO is involved. It's that this FOMO is one component of a mutually-buttressed system that deliberately incorporates friction for players."

From a developer's point of view, this all represents a fine line to walk. If you want players to be incentivized to go after six-star characters, then you'll need to design content that makes them interesting/compelling to use. However, there is always the risk that gearing incentives in this way will negatively impact players who don't access these characters.

There are other mitigating factors at play here. Another potential argument in favor of gacha-based games is the use of so-called "pity systems" - where after a specified number of "pulls"/attempts, you are guaranteed to receive a six-star or featured character. The challenge here, of course, is the question of exactly what the threshold should be for such a system (at any rate, I personally believe that these systems should exist for all gacha games in general). In some games, the "pity" may still require the player to spend over $100 per banner. A non-paying player might only earn enough free currency for one or two 10-pulls a month.

When I tried out a game called Nikke, I reached a hard limit on account progress. Even though the game had an excellent pity system, I simply couldn't make further progress unless I could get enough copies of the same highest-rated characters so that all my other characters could scale up to them. At that point, I either had to be super lucky on my pulls, or just spend lots of money on pulls. I did neither, and quit playing.

If you do manage to make solid progress in one of these games (especially if you do so as a free player, or a player who has spent lots of time and relatively little money), you'll still find that the experience begins to "narrow" as you reach late game challenges. What I mean by this is that late-game challenges set higher and higher requirements for access, such that you may need to spend a massive amount of time grinding. This, again, is fundamentally about funnelling the player into parting with more money. I'm already experiencing this in Arknights, where I'm really running out of gas at the moment. Yes, I have a lot of great characters, but I'll need to spend a lot of time grinding to level them up sufficiently. The time commitment will become so great that it simply won't make sense to me at some point.

No matter how great a game is, I don't think I'm the type of consumer who could ever play a gacha-style game as my "main game". These games - along with other live service experiences - typically demand at least some of your time each day in order for you to make reasonable progress. These demands start to become greater in the late-game, which becomes less practically achievable, which further increases friction, which incentivizes you to pull out your wallet. Is the requirement of daily interaction with the game itself a reasonable expectation? I personally think it's an unethical design practice.

Perpetual motion machine

The original concept behind live service games was that the game itself continues to grow in scope beyond the original retail purchase/release. The idea is that game might become a fundamentally different experience in years two, three, five, and so on. What I've found, however, is that even the largest and most successful live service games simply don't do this. Can you really argue that games like Destiny 2, Fortnite, Arknights, Genshin Impact, or any other long-running live service game has truly evolved and transformed?

The irony at the heart of these games - no matter how much fans might want to call them "forever games" - is that, ironically, they are designed not to change in some fundamental sense. This is because the monetization model works so well. And because it works so well, it has the practical effect of keeping the game - and the players - in a form of illusory stasis. It's illusory because the player has the constant sense that things are moving and changing: new characters, new banners, new battle passes, new cosmetics - these are all forms of additional "content". But if we take a step back and look at the whole system, it becomes clear that the design isn't a road leading to new destinations; it's a hamster wheel, encouraging players to run ever faster only to remain utterly fixed in place. Gameplay isn't driving monetization as we might expect, but rather, monetization models drive gameplay design decisions.

It should be noted that the model I'm describing here isn't applicable to all live service games. Warframe, for example, is an exception that proves the rule. Here's a game that has introduced a wide array of entirely new modes and systems over time, resulting in an experience that truly lives up to the ambitions and promise of the live service concept.

"But if we take a step back and look at the whole system, it becomes clear that the design isn't a road leading to new destinations; it's a hamster wheel, encouraging players to run ever faster only to remain utterly fixed in place."

There's also a catch 22 here for developers who adopt the hamster wheel strategy. The catch is that, by constructing such a tightly recursive system, they become less able to introduce brand new modes, enemy types, functionally new weapons, etc... that either a) breaks or b) ignores/doesn't utilise existing content. The problem now is that many players have invested hundreds - sometimes thousands - of dollars into that hamster wheel. If new content doesn't leverage or utilise the things they've already purchased (or is seen to negate their sunk costs), the pushback could be severe.

What follows is that, yes, new content is added. But it can only supply greater breadth - not depth - to the experience. Levels and enemies might become more challenging, but the core gameplay loop remains fundamentally fixed over time. You might be tempted to wonder: does this problem really matter if the Day 1 experience is so great that five years of the same experience should also be great? That might be a valid argument in some cases - especially for players who get in on the ground floor and really love the experience - but there are significant downsides as well. These games might have tremendous growth and receive massive recognition, but they'll eventually stagnate. One reason is that new players become less and less incentivized to jump in as the hamster wheel becomes large and unwieldy; the breadth of the game is now overwhelming, rendering it less approachable for brand new players. This means that, over time, such games rely more and more heavily on the "whales" (the longterm players who are also big spenders). But many of these players will ultimately tire of the game, stop purchasing, and ultimately stop playing.

Every single live service game comes with its peaks, troughs, and plateaus. And there is usually a point where - no matter what content is added or what incredible collaborations occur - an increasing number of players simply aren't coming back or aren't starting up in the first place. The largest and most successful games might still have a license to print money, but there will be a ceiling to this that will diminish over time.

End of line

There's another point of frustration I want to raise here and it relates to the end of service for mobile games. The beauty of digital games lies in the fact that they can be downloaded and played for a long time, but the mobile market is woefully behind in this respect. Love or hate them, thousands of mobile games released through the 2010s have been sunsetted, with servers being shut down. These games - along with all of the time, money, and energy that fans invested in them over the years - are simply disappearing.

"These games might have tremendous growth and receive massive recognition, but they'll eventually stagnate."

This is not only a problem for anyone who wants to continue playing these games; it's also an issue for game preservation more generally. I find it hard to stomach the thought of the many hours of work over months and years that a studio puts into a game only for it to go up in smoke, never to be seen again. Whether or not you're tempted to dismiss these games, the fact remains that developers worked incredibly hard to create and release them. They are human creative works that deserve preservation in some form.

Uncertain futures

When I wrote my book on free-to-play game design a few years ago, I discussed the idea that more mobile and AAA developers would look to games like Genshin Impact as the inspiration for their own projects going forward. We've really seen nothing totally novel in terms of mobile design and monetization since. Multiple developers have sought to capture their own lightning in a bottle by aping Genshin Impact's design.

The bigger question I have is whether or not we'll see new - and potentially more ethical - monetization models emerge and become popular. Despite the success of gacha models to date, there are - as I discussed throughout this story - various risks and ceilings that developers are increasingly likely to bump into. And beyond that, there remain serious questions about how the regulatory environment may change in coming years. Will leading economies like the U.S. or the E.U. put in place new laws designed to curtail - or even outright stop - unethical forms of monetization?

For more on free-to-play and mobile design, be sure to pick up my book: Game Design Deep Dive: F2P.