Finding My Monopoly

Exploring the author's journey from unsatisfying Monopoly games to hidden gems of economic critique

I hate Monopoly. In my time playing games, I’ve picked up on a few things that bug me about how Monopoly is designed. I’ve also found better alternatives that I would be hard-pressed to introduce to family game night. The nausea that sets in whenever a friend suggests we pull out some themed version of Hasbro’s flagship board game began upon revisiting the game after having dove headfirst into the world of complicated board games. Some gameplay elements were blatantly disrespectful to players who fell behind or didn’t make collateral for trades before the board state was set.

I wanted to know what made this game so popular, and why the rules deliberately create winners within the first two to three rotations around the board. So that's what I did, and the results are here for you, dear readers.

How Monopoly came to be

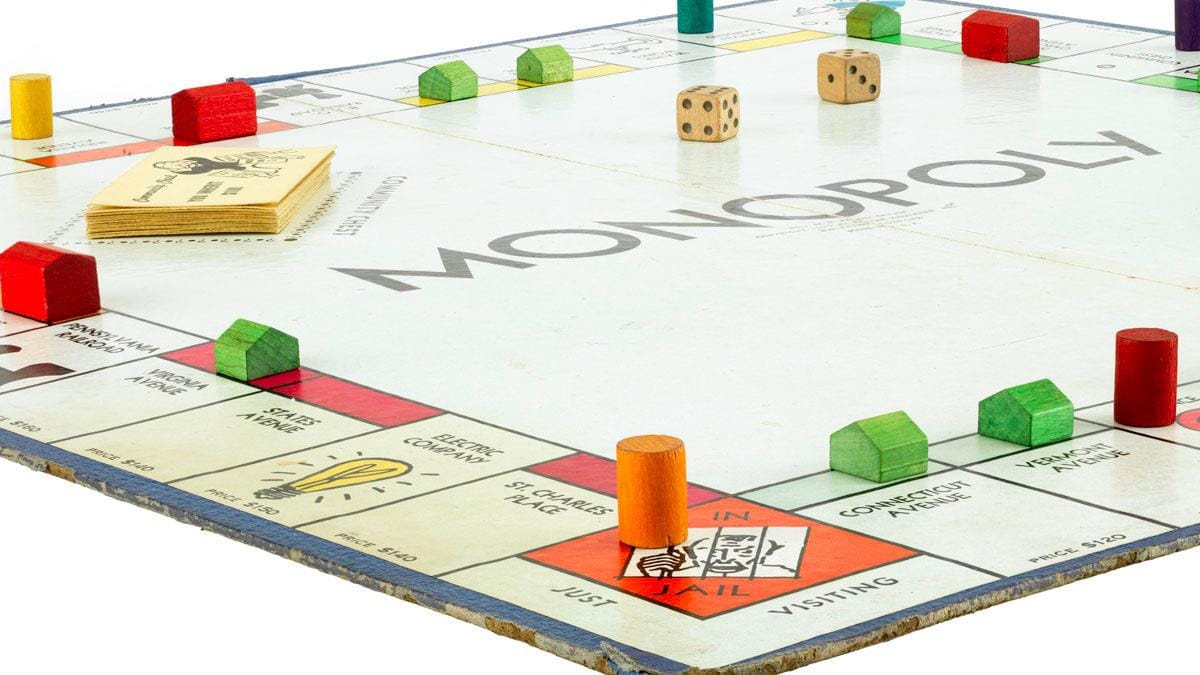

In 1935, Charles Darrow was unemployed and dreamed up the game of Monopoly which he then patented, commissioned a friend to create art for, then sold out of a local department store.

But, that’s not entirely true. To understand Monopoly, we have to go back three decades to 1903.

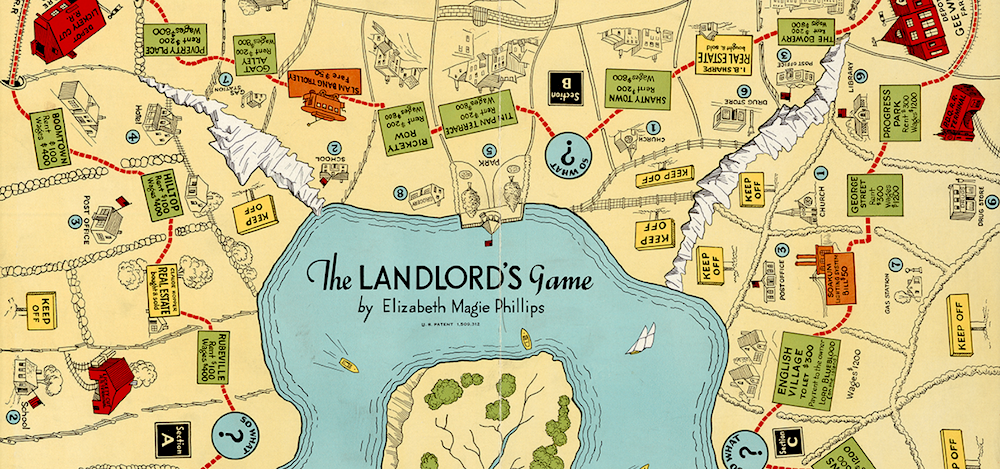

Elizabeth Magie, a staunch “single taxer,” creator of the arts, and successful woman in her own right, created Monopoly to spread her own strong-held political beliefs in the form of economic simulation. Board games in this time were not typically made to escape into fantasy as they are today. They were war simulations, educational tools, and (in this case) political statements.

As a single taxer, Elizabeth was a strong supporter of economist Henry George and his ideologies. George believed that land couldn’t be owned, in the same way that no one owns the air we breathe. Single tax refers to the one price you pay to your community to grow your public amenities while things like rent and income tax become nonexistent.

In a sense, he believed that everybody “rented” land from the earth. He believed that a person deserved to gain all the profit they accumulated with what they built on that land. Any person would be taxed based purely on the amount of land that they used and not the money they made on it.

The Landlord’s Game was created in protest to the Carnegies and Rockefellers, to warn the people what would happen if one person could own everything. The game was mostly spread through word of mouth and went through several iterations before landing in the hands of one Charles Darrow who swore that this was his game.

Monopoly was not created to be a game that was fair. It was created to show you how unfair the capitalist dystopia we’ve created is. In that regard, Monopoly is pretty cool! But not as a game.

Monopoly's poor-punishing mechanics

The game mechanics of Monopoly include creating possibly the least dynamic turn possibilities in any board game that I’ve played. This starts with my least favorite game mechanic in any turn-based game: Losing a turn.

The jail in Monopoly is iconic. Everyone knows “Go directly to jail, do not pass go, do not collect $200”. Inherently, when playing a game nothing hurts more than not being able to play. A positive alternative to this would be to let players take extra turns in a row, which would functionally give the same advantage to other players as sending you to jail. That being said, in some cases, jail can actually be the safest place to await the end of the game so that you can watch everyone else lose first.

The most insulting game mechanic in Monopoly is the tempting stack of Chance and Community Chest cards in the middle of the board. There’s no worse feeling than getting $50 when rent is $400. The cards have a chance to reward a player's good luck in landing on them by offering rewards that scale with the state of the board or giving that last place player a chance to steal that one property they need to get back in the game. Instead, paltry offerings amount to a system that keeps the low-income down until rent swallows them.

Culdcept and Talisman

My last experience with Monopoly was the one that showed me exactly why I couldn’t stand the game. A friend of mine put four houses on each of his properties without upgrading all the way to a hotel. When no more houses are in the bank, no more houses can be purchased. The Monopoly was not only referring to the properties but the houses as well. This stops anyone else in the game from making any sort of improvements to their properties and secures victory. This is actually a fairly common strategy among people who have taken it upon themselves to try to be good at Monopoly.

After having taken a sabbatical from games that include rolling dice and moving around a board, I found myself thrust back into it by a game I found while collecting PS2 titles. I saw this at my local retro game store by chance and decided to pick it up for my collection, and I’m glad I did. Culdcept is a board game RPG that was developed by OmiyaSoft. The original inception was released in 1997, however, this particular PS2 copy was the company's 2001 second edition.

Often referred to as the bold combination of Magic the Gathering and Monopoly, Culdcept has its players form a deck of collectible cards that they play on colored spaces around a board. These cards become monsters that will attack foes that happen to land on your space. The game had a large luck element, but rewarded preparation and smart deck building.

I found Culdcept a blast to play, thinking it had solved many of the gripes I had with Monopoly. Allowing the player to make their own decks, much of the luck fell on the deck-building prowess of the player rather than the whims of the game. Most importantly, there was always a way to topple the monopoly if you brought the right cards. Killing opponents' monsters would clear up a space to allow other players a chance to occupy that space.

Culdcept reminded me that through the magic of game theory perhaps any game that I disliked could have rule changes that made it more suited for me. Maybe I could find my version of Monopoly.

This thought struck me right before I accepted an invitation to play a very long board game, called Talisman, at a friend's house. Talisman was first released in 1983, however, the version we know today is the 4th edition which was revised in 2007. In the game you roll a 6-sided die, move your character to a space, and then draw a card and do what it says. A simple game, it ends up becoming a monster to play and one of the grandest adventures you can put on your table.

When I tell my friends about Talisman I say that it’s fantasy Monopoly. I always preface it this way because the game is almost completely luck-based, and involves rolling a dice and moving around a square board. Close enough. My first experience with Talisman was grueling but magical. I sat at that table for 12 hours during which I learned that with all of the expansions, Talisman could open into a large world in which anything (good or bad) could happen.

Successive games of Talisman would reveal that unfortunately, this game is more like Monopoly than I care to admit. This game is riddled with cards that force players to skip their turns, a race to the middle that leaves the last thirty minutes of the game a march toward doom for all losing players, and interaction that typically has players tripping up their opponents “just to do it” rather than for real strategy. I still prefer the death throes of Talisman to the rent inflations of Monopoly. With Talisman in my rearview, I couldn’t help but think that there had to be something better. Somebody had to have made a game that improved on the formula of rolling a dice and moving around a board since 1903.

Enter a game introduced to me by my own research, Relic.

Relic

Relic is a Warhammer 40K-licensed board game released in 2013 by John Goodenough and Jason Walden that uses the rule set of Talisman as a base. Relic fixes everything that I disliked about Talisman. It’s not perfect, but it provides a solid game in a good-looking package that is completable in an afternoon. The leveling system makes progression meaningful and achievable. The explosion system makes each fight lethal and exciting. The mission system makes sure that each player always has a goal in mind as opposed to Talisman's aimless wandering to get stronger.

I often go entire games of Relic in which not one player ever skips a turn. There is a feeling of limitless progression with the rewards being hard won. I had finally found my version of Monopoly, at least until they make more Culdcept games.

I’ve often gone back and forth about all of the games talked about here. The beautiful thing about board games is that you don’t have to let the rule book tell you how to have fun.

I have so many notes on how to change Monopoly and Talisman to make them more like Relic and Culdcept. I’ve even gone as far as dreaming of a game of my own that falls somewhere in the middle of all four of these games.

Conclusion

My quest to find the best version of Monopoly taught me two things. The first was the actual lesson that Lizzie Magie tried to teach us with Monopoly 120 years ago, that monopolies break capitalism. The second was the introspective one: when it comes to my own fun, why not find or make the games I want to play?

Maybe you can take something in between; don’t settle for that big AAA studio game everyone is playing if you can dream of or support something the world's been waiting for.