Final Fantasy VII: Rebirth Is Helping Me Write More Fearlessly

Aiming for joy

"We all give up great expectations along the way."

The Angel's Game, Carlos Ruiz Zafon

When I was a kid, I wrote. A lot. My first attempted "novel" was a portal fantasy inspired by a casual perusal of the D. J. MacHale YA series, Pendragon. I wrote it during class, during lunch, during recess, at the kitchen table. It was around 30 wide-spaced elementary school pages of completely uncorrupted words. I never left home without a notebook or a sketch pad or, eventually, my laptop. If I didn't have them, I'd find a pen and use the back of my hand, or a stray receipt, or a church pamphlet.

These quirky little habits were things I ascribed to an predestined literary ascendancy, rather than the squirrel-like affectations of a budding lifelong creative. This was it, I thought. I was going to grow up to be an author and die with my fingers on a keyboard. But as the years wore on and no finished novel emerged, I recognized that my imagined career behind a mahogany desk sipping whiskey and building worlds would inevitably become a clandestine hobby done instead on early mornings and late nights, bookending days spent in a dull grey office, and that I would, ultimately, die with my hands on a keyboard – it just wouldn't be my own. I came to reflect on my fateful history with writing as a Sisyphean failure.

This was a life of setting perpetual deadlines, of having goals that stretched out indefinitely, of resenting jobs instead of actively doing them because I was busy bemoaning lost hours of writing instead of trying to make things better. This was a life of hosting frequent pity parties for myself and the bleak unfairness of having to actually give a damn about the world around me and not just the inner one I wrote, retreated to, and pedestaled as some kind of secular creative ordainment. I tweaked scenes over and over again, not even improving them, just trying something different that would sate the invisible, monstrous internal audience I'd spent a decade cultivating as phantoms of my own judgements. Writing became my boulder, and I was drolly, miserably, tiredly rolling it up that hill every day.

Final Fantasy VII: Rebirth has a lot to say about creative freedom, and what it means to interact with the stories you create. It's helped me peer past the drudgery that writing has become (What if my dialogue stinks? What if I don't represent this particular thing well? What if I end up on a Tik Tok naughty list? What if my writing isn't good enough? I should change this, or this, or this) to see what, exactly, I've been missing: writing something that doesn't give a damn about everyone else.

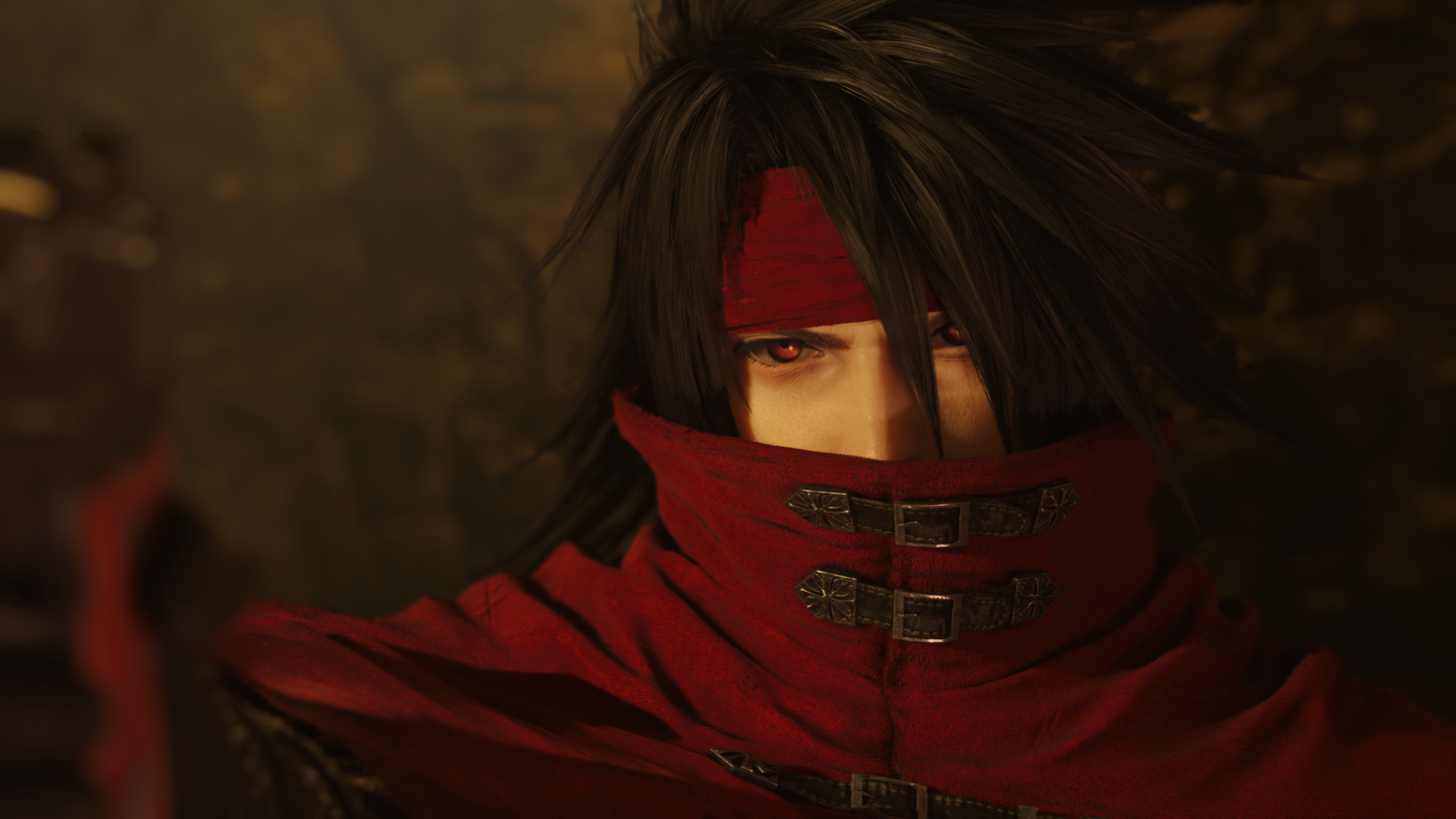

Final Fantasy VII's story has always resonated with me. Some of the earliest drafts of my current novel were lifted directly from the love story of Zack Fair and Aerith Gainsborough. I loved that little flower girl. I still do. Two decades separate me from my first encounter with her, but I still can't shake the influence her character had and continues to have on my stories. I've always been a fan of tragedy, of melodrama and melancholy, and the fantastical elements that bolstered Final Fantasy VII's exploration of those did me a great service creatively.

Rebirth is, in a word, about wonder. The world is full of wonder, the characters are full of wonder, the story is full of wonder – the very essence of Rebirth's exploration is in the wonder of its extant essentialisms. Years of passionate but toilsome writing have turned me into something of a bitter critic, so wonder is a relatively dusty corner of my creative mind. I've written dutifully and with didactic necessity for so long that letting that go in favor of "winging things" feel absurdly impractical and, in a way, disingenuous to the art.

But every aspect of Rebirth – the open world, the towers, the Lifesprings, the area-specific chocobos, the shrines to summons, the harder hitting plot points, Cait Sith, even that damn feeder-clanging chicken mini-game in Gongaga – is pretty much winging things. Not all of is succeeds, but Rebirth is a lesson in this sort of free-floating fun, and it feels so much a counterpoint to everything that Final Fantasy XVI was trying to do. And listen, I know, it's a comparison that every Final Fantasy fan is currently making, and I won't belabor on it too much but to say it made me realize something about the cognizance of peer-aware writing. I think Final Fantasy XVI is a solid story with lovely moments and stunning boss fights; but I had to force myself to finish that game's major side quests, never mind the hunts or arenas, whereas in Rebirth I look forward to nearly every incidental.

So I had to ask: why exactly is that?

Earnest imperfections

I believe I know the reason for this: the 30-member core development team of XVI had to watch all of Game of Thrones as research. Obviously, this was a means to mimic the "feel" of the gritty fantasy, but then the game still had to adhere to Final Fantasy's particular brand. This was a felt dissonance throughout. XVI's decidedly creepy antagonist blunted the impact of the game's smaller political machinations and funneled all the hard work of reclamation and justice to a single source: our indefatigable hero.

It felt to me as if there was a commitment issue here; XVI wanted to be a stand-out Final Fantasy game aimed at western audiences, and it purposefully tailored itself to that, but I felt completely unmoored from its larger world, and I think that has everything to do with the game's quiet fear of brushing too close to that oft-mocked sense of clunky Final Fantasy sincerity. The characters are more somber and serious and while this works to a certain extent, I kept feeling like they wanted me to see this not for what it was but for what it was trying to be. It was a very thoughtful and well-plotted game, but also somehow less confident, because it felt like it was attempting to – quietly, perhaps unconsciously – prove itself.

While Rebirth certainly had a lot to live up to, proving itself to that same degree wasn't one of those struggles: it just had to be the best version of VII it could, and the writers seem to understand that the inherent competition wasn't external, but internal. Instead of bucking the indulgences they get a lot of crap for, they whole-heatedly embraced them, and so it comes across as a more honest experience.

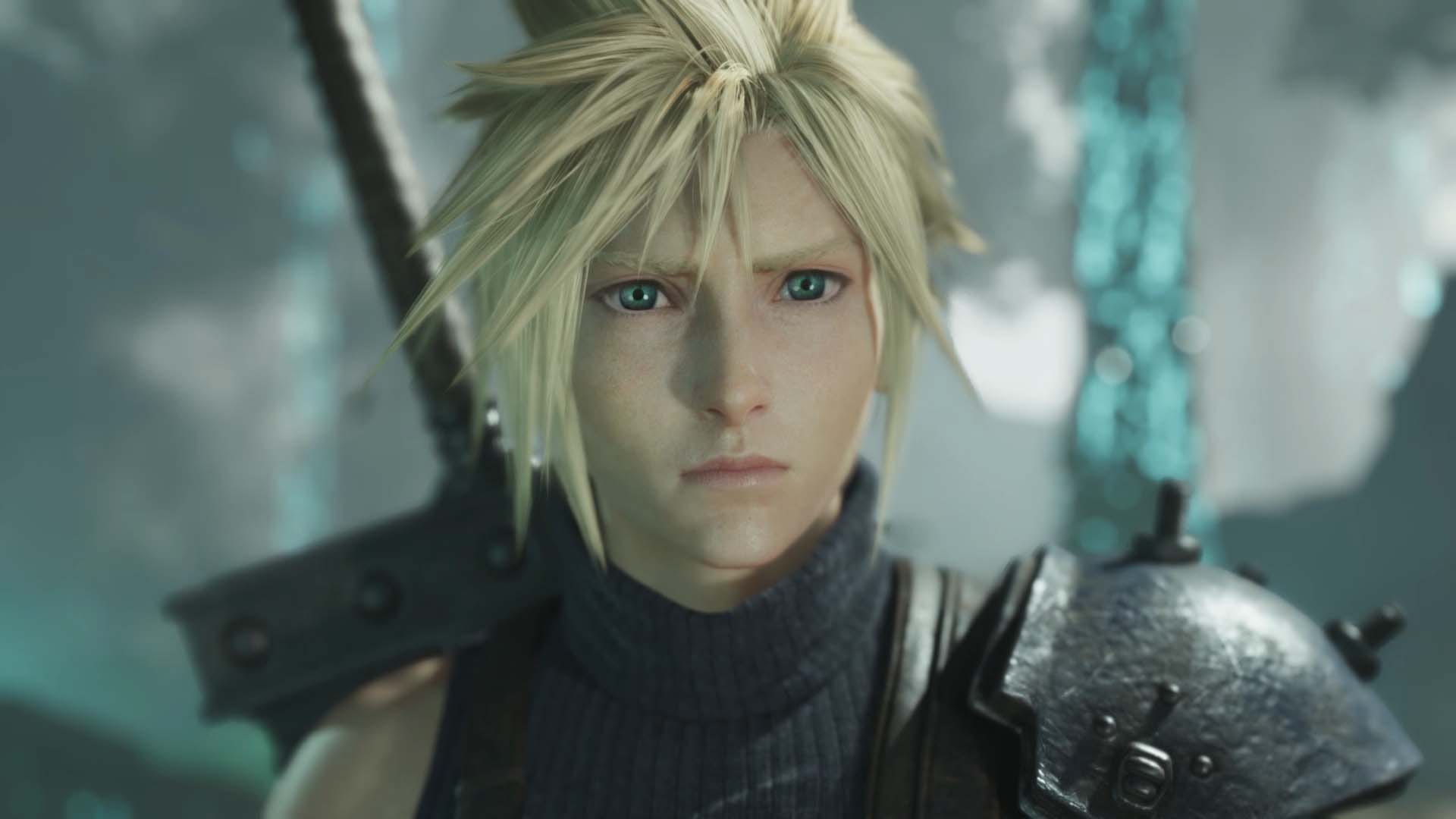

For nearly all of Remake and Rebirth, Cloud is a blank and haunted soul, projecting a sort of dull-eyed insouciance to his fate, aggravatingly complicit, pitiably unstable, and he's more interesting because of it. Like Clive from XVI, he is connected "by fate" to his antagonist, but Cloud is not the focal point of his story: he is a happenstance that manages to become an inconvenience.

We're meant to be rankled by Cloud's position as both unwilling host and fatalistic participant, catching glimpses of his potential fate as a black-robed zombie that sting because of Cloud's already doll-like whatever-isms. His lack of self-worth – really, his lack of self-love – is part what makes his journey and its interwoven drama so memorable. The other part of that is in the fact that he's also a bit of a dumb-dumb, and his moodiness is at each turn made fun of and made serious. There's room for us to maneuver his characterization, and that's where the real magic is.

For the majority of Rebirth, we control Cloud, but not for all of it – there are sections that belong to Barret and Nanaki or Yuffie, to Tifa and Aerith. We flesh them out to a greater extent here. Tifa gains depth as a thoughtful person very conscious of people's view of her, and lacking a confidence that we, as an audience, might feels she's more than earned as swagger. It's endeared me so much more to her character because she's very like Cloud in that sense – it's a question of self-worth.

We control these teams during battle, switching them out on the fly to assist one another. This allows us to see how they unite and exist and bond outside of Cloud as well as with him, using wacky, nearly slapstick, and sometimes really quite sweet animations that showcase their relationships and display their ties clearly – and they have fun with it. In one synergy move, Aerith dons Barret's sunglasses, and in another, Cloud helps Yuffie up after she falls launching their joint attack. They are extraneous little glimpses of relationships communicated in-game, in-play, and these dynamics made me realize one thing: imperfect and exaggerated as they are, Final Fantasy VII's characters are simply fun to spend time with.

What's worth telling

Rebirth's ruminations on life and death and purpose are also baldly stated. Zack is a foolhardy optimist, Biggs is a guarded do-gooder, and there's a speech in a middle chapter with them about making a life for yourself even if everything sucks. Of course it's on-the-nose, but it hits, because I get that – we all get that. Rebirth is strengthened by this ability to be idealistically kind to us, its characters, and its world. It feels safe, even when it isn't, because it has shown us that it cares. It front-loads its ideas, plowing into us with flowery meditations on loss and moving on and friendship that I feel I've been encouraged to doubt by an art culture steeped in incurable realism. Grandiose displays of emotion are too often relegated to "cheese", when the triumph of them is in their candor.

This is why the bombastic elements work. The Loveless portion, a choreographed musical that unfolds at the Gold Saucer later in the game, shines as an expression of pure, unabridged VII energy: the whole cast dressed as characters in a play, with Aerith, the star of an emotional finale, singing directly to us, the audience, and her friends. It seems like a wonderful time for the development team, and that energy shines through. It feels like a rarity. They got to spend portions of their game luxuriating with their characters in sequences that still convey emotions tied to the main story. They genuinely love this cast, and so we do too. Rebirth's occasional lack of nuance is lifted from dilettantism by these little things – the shifting leitmotifs, the asides, the circling back of old plot points, the set pieces. It's even evident in the extended cast.

When we get to the Corel region, we meet the gold-toothed, finger snapping "King" of Corel prison, Solemn Gus, a reconfigured character from the original game, who is absolutely ridiculous. Already we have the white-coated villain of Rufus Shinra and his many belts, the well-dressed and fairly competent Turks, not to mention Gold Saucer's body-building good-guy Dio, and eventually Cosmo Canyon's Bugenhagen with his...floating crystal ball. A cool-headed, unruffled Cloud meeting all these patented personalities is telling, because it showcases just how much of a non-entity our main dude thinks he has to be. It's illustrative of individualism as a representation of self, not as an assertion over others, but as means of sharing selfhood, of melding with and loving and getting annoyed by peoples of all sorts who are unabashedly themselves.

Each Queen's Blood player has their own quirk – a drunkard, a cry-baby, a dog – that further serves to remind us of how bright the world is, how worth saving the people in it are, and how dull Cloud is against all of it. This is the setting knocking on the door of his narrative, letting us know this is his struggle: he is peering into a party from the outside, not sure if he's been invited. Rebirth's world informs its story, and the cast is so idiosyncratic we might perceive them as unrealistic, but they're just real personalities made stronger, traits honed and focused, and while seemingly elementary – in that you're populating a world with caricatures – it feels like a genuine celebration of people.

The everything-but-the-kitchen-sink style of story building feels very Dungeons & Dragons, because of course it does – it's the random, often unscripted "why nots?" of the story that make them so human. It's a roll of the dice. I don't watch live plays, but I have friends who do, and I know those stories resonate because they are built collectively. A freeform style is often complimentary to the Rule of Cool (and, functionally, the Rule of Fun), which doesn't give a damn about how practical something is, as long as it can merit its existence by sheer level of awesome. The buster sword is like this. How does Cloud lug that thing around? Doesn't matter. When we start to infuse realism with something to make sense of its outlandishness, or to explain it away as if we're ashamed of it, we can lose that ephemeral sense of whimsy.

The best stories, I think, are the ones we tell to ourselves.

This was my longstanding issue as a writer: I was adhering to a vision directly competing with other stories and too concerned with first impressions to have fun. I didn't want to be messy and so I started to give a damn. I cared about what it might become or how it would be received. When this is the motivation, your story then has to prove something, it can't just focus on characters exploring trauma or loss or reluctance imperfectly as you might, because then it's too sincere, and that's cringe. This isn't all happening in your dollhouse anymore, kid, you've got an audience now! It feels like you have to tiptoe around impulses to have fun with your world. This is where authorial intent can rob the narrative of that latent sense of imaginative joy, because it becomes afraid of its heart. The best stories, I think, are the ones we tell to ourselves.

Rebirth, obviously, isn't necessarily the best example for this. It's in constant conversation with its own legacy, so not really an independent venture of world-building, frolicking fun, but dammit if I'm not having a blast with it. This is a theme park of Final Fantasy VII's characters, themes, core concepts, and music, and there are moments of genuine joy and grief that reflect my early experiences with the series. I care about this world. I haven't had this much fun in so long with a game, and I think that's an important thing to hone in on.

You can't exactly ignore the firmer pillars of what makes a good story or good character arcs or good writing anyway, so there is a measure of command the audience expects, but it doesn't have to do everything right. We expect flaws, that's what makes this whole thing more fun. My favorite horror director, Mike Flanagan, relishes monologues and other auteurish tendencies in his intensely personal series, Midnight Mass, but it is done with aplomb. It explores the ramifications of religious monomania, something he personally connects with, and like all of his work, the love he has for the characters is achingly tangible and his personal touch means something. Having a conversation with tropes or styles or genres or can be a proper exercise, but what matters, what the audience feels, is why.

Finding your voice

By long coddling my ego as a creative, it's allowed me a pedestal on which to stand, where I can look at the ring but never actively participate in the fight until the thing I've created is absolutely perfect, blow-your-mind amazing. Which is impossible and also, like, really self-aggrandizing. I've placed great expectations on myself because of it, needlessly burdening my writing with a finessed wit that I hope will come off as really smart. I studied the craft. I read the scripts. I learned the art. I perfected the words. Now what? I want to lock horns with best-selling writers...and for what? Who am I trying to prove myself to here, exactly? My little imaginary strawmen? That languishing audience in my head composed of pretty much everyone who ever told me I wasn't good enough? I keep writing for ghosts and it feels more and more pointless.

Cloud resonates as a character for me because I, too, feel prisoner to an identity I've imposed upon myself. I fear being me as a writer because I don't think I have anything more valuable to say than anyone else. I think everyone's work matters, so in the scheme of things, does mine? And then I know at my heart is a pretty haughty thing – proud and snide – so I fear I'll write something you can peer beneath to point at, "aha!"-like. I don't want to sound sentimental or overly emotional, so I seed my writing with wry commentary or try to divert criticisms by premeditating them, and so there's hours dedicated to covering a scene's potential weakness. I punch high, duck low, and don't want to get hit. So when I see Cloud applying outside influences or external perceptions to try to "cover" those parts of himself that he's ashamed of, I get it. His mortar is brittle. Seeing him fall victim to this always hits me hard, because it's not really a fear of how you appear – it's a fear of not being good enough for those you care about and even those you don't.

I have plenty of Schrodinger's novels that my friends and family have been aware of for so long they've stopped asking when I'll finish, because the assumed answer is always the same: almost done! But not really. It's an excuse to set those goal posts ever farther away. I don't want to be finished because then it's all out there, and everyone else will be able to lob their big ol' bricks at my little glass house and cup their hands to peer inside it. And so what?

All I truly, honestly want to do is craft hard souls who find kind places, for me, for my joy, hopefully for the joy of others, and everything else be damned.

It's not easy either – we walk a tightrope of want and need and reflection and curiosity and honesty in stories in a society increasingly obsessed with snapshot reputations and perceptions. We are our own abysses, after all – and baring that is going belly-up to an audience primed with waiting teeth. I've spent a lot of years grumbling and caustic and, yeah, work's a slog, nothing's fair, America's a failed state, but I gotta plant trees somewhere, and I might as well do it in my work too.

It isn't just Rebirth that's helped me re-realize creative freedom, it comes on the heels of the recent millennial acceptance of not giving a hoot, as well as trying make little differences every day, and in understanding that we're all pretty much here to fart around – so it's nice to witness that fundamental play of storytelling in action.

There's real joy in being able to cuddle up to an experience I grew up greatly influenced by that feels so genuinely itself, so brazenly goofy, so starkly solemn, so brightly wondrous, that I remember exactly why I wanted to write in the first place.