Feminism and Trauma in LISA: The Painful, Part 1

Through the tortured upbringing of Brad Armstrong, LISA depicts a tragic interpretation of toxic masculinity

In a world where women mysteriously vanished, society has collapsed into warring factions of drug-addicted, alcoholic, scavenging gangs. Every day is a fight for survival for the men living in the scorched desert canyons of Olathe. Then, one day, a girl just as mysteriously appears, and society somehow gets even worse as all the men in the world brutally fight over her.

Our protagonist, Brad Armstrong, who has male-pattern baldness, a long scar across his right eye, and strong arms, is looking for his daughter. He encounters a shirtless burly middle-aged ginger man who runs an orphanage of six downtrodden young boys. Tommy is playing with matches again. Now there’s an open fire, and ginger man asks Brad to grab a bucket of water to put it out. Uh oh, it was gasoline. He grabbed the wrong bucket, and now the children are on fire.

This is LISA: The Painful RPG in a nutshell. It’s probably the best game ever made. (According to me.)

LISA: The Painful is a product of the indie game renaissance in the mid-2010s, and like Undertale, it's a spiritual successor to EarthBound. It's, well, a game about pain, the cycle of abuse, and how the player is made to feel the same pain as Brad through ludonarrative storytelling. When critics talk about LISA, they usually bring up how it was one of the most punishing video games of the 2010s, how on hard mode you can only save once at sparse save points before they blow up, but especially how the game forces the player to make impossible choices.

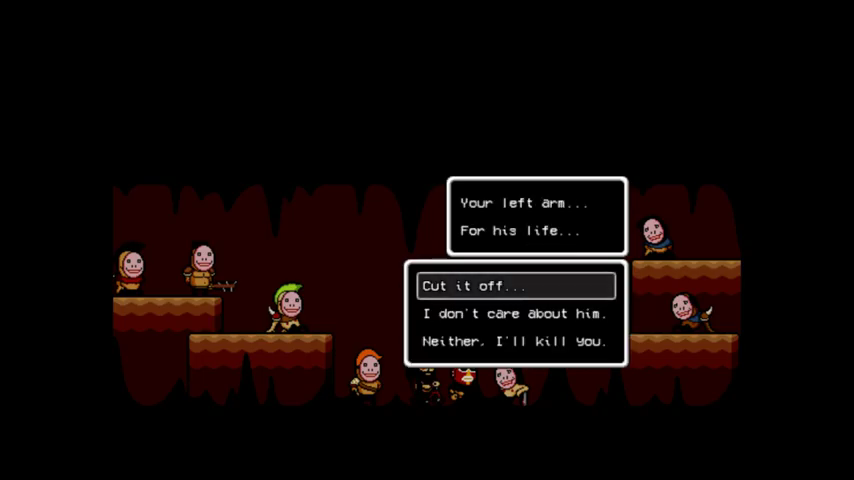

At several points, Brad ends up in losing fights with rival gangs, and the player is forced to choose between losing all their hard-earned money and equipment, an ally’s life, or one of Brad’s arms. Unlike other roleplaying games where party members are easily revivable, enemies in LISA can permanently kill your allies, and there are only so many of them. These decisions significantly influence the game’s challenge factor. Brad relies on a form of martial arts that uses his arms, Armstrong Style, so the loss of one or both of his arms makes him near useless in tough fights, and he can’t be removed from the active party.

In his video essay on LISA, Harry Brewis, host of Hbomberguy, explains how the gameplay loop, while frustrating, is balanced in such a way that discourages loading a save file. “It’s one of the few games where I’ve had a bad outcome, lost someone in a hard fight a few hours out from my last save, or almost all my party to Russian roulette, and continued because I’d come so far and didn’t want to go all the way back or, worse off, didn’t know how much worse it would be if I tried again,” he says.

I’m an English major, so when I tell my peers that this, the game where all the women are gone, is one of my favorite literary experiences, I get weird looks. But the reason this game intrigues me is for reasons I’ve never seen represented in literary criticism on LISA. While the game’s ludonarrative triumphs are worth mentioning, no article or video essay to date has fully put all the pieces together as to why LISA is so painful and why it told the story the way it did.

LISA is a game about toxic masculinity.

It’s really strange to me that no one’s brought this up. Hbomberguy, a major player on LeftTube, doesn’t talk about LISA from a feminist lens at all in his analysis. Hardcore Gaming 101’s Jonathan Kaharl briefly mentions “the entire world [of LISA] is one long satirical jab at heterosexual guy norms,” but doesn’t go into more detail. Some of the early discourse around the game even described it as “anti-feminist.”

I think the lack of attention to LISA’s feminism can be explained by quotes from the game’s creator, Austin Jorgensen, so let’s talk about that. “I love it, because with LISA, every website is selling it as a world without women, which is true, but it’s also just the backdrop to the game – the game has like… nothing to do with that subject; it’s just the world they live in,” Jorgensen told Hardcore Gamer. “But my goal with Lisa is to have no agenda or message; I don’t care about that sort of thing, and I’m not going to preach any side on any issue; at least that’s my goal.”

To most people, LISA cannot be about toxic masculinity or feminism because the author said so, end of discussion. But I don’t think this is the complete picture. Based on what Jorgensen said, it sounds like his primary goal was crafting a realistic world on the premise of a woman-less apocalypse with “good gameplay that makes you care about the characters,” and whatever themes came out of that, the chips would fall where they may.

What I’m saying is that since Jorgensen’s authorial intent had nothing to do with themes or agendas, and since every piece of textual evidence points to toxic masculinity, it’s reasonable to hypothesize that Jorgensen rolled the dice and ended up crafting a theme with feminist outcomes, whether he intended it or not. So, instead of rejecting this theme outright because of quotes from the author, hear me out and take a look at what the text of the game says directly.

Here’s what I think the game says after at least a dozen playthroughs: There are no heroes in LISA, only a society of strong, broken men who make the world worse for each other and, most of all, one traumatized young girl. LISA’s world, with few exceptions, militantly enforces traditional gender roles and isolates men from the world of emotional expression, aside from anger and lust. The game drips with hyper masculine imagery from its harsh terrain, fetishization of strength, and its eclectic, sometimes bizarre soundtrack, from low bass drops, ‘80s motorcycle vaporwave, intense drumlines, and baseball motifs. Between Brad, traumatized at the hands of his father and schoolyard-bullies-turned-violent-gang, his subsequent abuse of his daughter Buddy, and the vast majority of predatory men on Buddy’s trail, LISA tells a harrowing story about the cycle of abuse, showing why toxic masculinity exists and how it negatively impacts women, and men too.

Brad Armstrong at a Glance

Brad Armstrong is not okay.

He might be our protagonist, and sometimes he means well, but he’s far from a good person. Despite his faults, he tends an easy character to sympathize with during the first half of the game. Brad is realistic to a fault. It’s hard to come out an upstanding hero when you know nothing but violence in a hyper masculine upbringing, and in many ways, Brad shoulders the burdens and struggles those men face.

In other words, Brad struggles with the social norms and pressures of toxic masculinity. The American Psychological Association defines toxic masculinity as a phenomenon where “boys live under intensified pressure to display gender-appropriate behaviors,” where cohesion as men in society depends on performing macho attitudes, suppressing “emotional sensitivity and … connectedness” out of fear of appearing feminine or gay, and reproducing sexist attitudes toward women. Potentially, this may escalate to bullying, assault, verbal aggression, or intimate partner violence. Contrary to some critiques, most feminist scholars do not believe that all expressions of masculinity are toxic. Rather, they understand it as socially constructed and continually reproduced between peers and from generation to generation, making it difficult but not impossible to reverse.

We see this socialization of toxic masculinity happen to Brad as early as the opening cutscene, where he gets beaten severely by schoolyard bullies for trying to protect his friends, Rick, Sticky, and Cheeks. This is the first of many fights Brad loses against physically stronger men. He’s covered in blood, his clothes have been torn apart, and he seems to be suffering head trauma, but when he stumbles home, his father Marty, who’s watching TV while drunk, isn’t exactly proud of his son for defending his friends. In fact, he isn’t worried about his son’s injuries at all. “My son steps into my house. Beat to shit,” Marty says before throwing a beer bottle directly at Brad’s head and shouting, “I’m not buyin’ you another shirt.”

On the way, a neighbor says to Brad, “When will you ever learn?” Learn what? Don’t bother doing the right thing if you’ll lose the fight? That Marty wouldn’t care if Brad assaulted innocent people as long as he came home with his clothes intact? And remember, this display of violence comes before the mysterious flash that kills all women, showing that the hyper masculine world of power predated the apocalypse.

At this stage in his life, Brad wants desperately to help others but just doesn’t know how to do so outside of physical violence, or in a way that doesn’t get him in trouble for losing. Brad goes upstairs to his room and cries as the title card materializes on screen, one of the only times we see such an overt display of male emotion before Brad turns into… this.

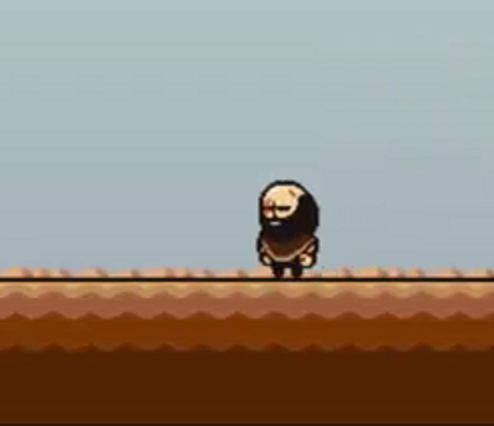

Brad’s character design for the rest of the game is haunting. Harsh, rugged features. An intimidating beard. Dark, impenetrable shadows over his eyes. War scars on his right eye and forehead. This is the stoic, emotionless face of male suffering. It’s the face of someone who has cut himself off from the world of feelings a long time ago. The most striking example of this comes toward the end of the game, when he says Rick, Sticky, and Cheeks “don’t know me.” These have supposedly been his best friends since childhood. Brad has never been comfortable talking about his feelings with anyone, including his best friends, after some 40 years. This isn’t just Brad – talk to most older men, and you’ll hear the same thing.

So, when Brad stumbles across the last baby girl in the known world, abandoned in a desert canyon, the question of the hour becomes, “Does this encounter change him for the better?” When he carries her back to his shared home with Rick, Sticky, and Cheeks, he insists on keeping her a secret from the rest of the world on the grounds that “She wouldn’t stand a chance out there,” despite Cheeks’ protests that “we’d be set for life” and Rick’s point that “The Rando Army would be better equipped” to raise her. Brad doesn’t care because, in his words, “This is my second chance.” He’s referring to his inability to protect his sister, Lisa (the protagonist of LISA: The First), from the abuse of their father, and her subsequent death.

This sets the tone for Brad’s character arc, and puts all his motives into question. This single line taints every well-meaning interaction with his adopted daughter, Buddy. It becomes clear that Brad doesn’t fully see Buddy as an individual, a person with autonomy and a personality separate from Lisa. Any woman who miraculously appeared in his life would have filled the same role for Brad: an object that fulfils his futile fantasy of going back in time and having the strength to save his sister.

This leads into a short montage across the next 13-ish years of Buddy’s life. And, shocker, Brad is a bad dad. I mean, there are some happy moments. Buddy gets Brad to let her put makeup on him (oh, we’ll get to that later), and they go on walks. They even pick a flower, which becomes a motif of their father-daughter relationship. We see that there are moments when Brad breaks free of his inner demons and flaunts traditional masculinity in a way that actually improves Buddy’s well-being. At other points, Buddy is seen in the basement crying while Brad, stone-faced, is surrounded by beer bottles and the performance-enhancing drug Joy, which according to its item description “makes you feel nothing.” Brad has inherited his father’s substance abuse problem and has Joy-addled PTSD hallucinations of his father. Brad tries to quit at several points, but he falls off the wagon every time, unable to escape.

The short-lived “peace” ends when Brad returns home one day. Rick and Sticky are nowhere to be found, and Cheeks, in his dying breath, tells Brad, “Secret’s out. She’s gone.” As readers, these four words clue us into this moment as the inciting incident, the turning point. We're left to ask, will Brad's quest to save Buddy change him for the better? Or is the war for Buddy an omen of destruction for Brad, Buddy, and the world of Olathe at large? Either way, in a world like LISA's, it won't be a painless journey.

If you're intrigued about the masculinity themes of LISA, stay tuned for the next articles in this four-part series. Part 2 will dissect how the gameplay mechanics set the psychological stage of the game's characters and circumstances. Part 3 will compare and contrast Brad and his friends with the brutal rival gangs of Olathe. Part 4 ends the series by discussing LISA's commentary on mens' possessive attachment toward stereotypical womanhood at the expense of self-reliance and platonic intimacy between men.