Don’t Kill My Vibe: The Problem with Combat in Control

Control's bombast is at odds with its uncanny ambience

I may be late to the game — both literally and figuratively speaking — but since entering the world of Control, it has captured my imagination and no small part of my thinking since. For anyone who’s played the game, you’ll probably have a good guess as to why: namely, the incredible in-game world created by Remedy Entertainment. It seems I’m not alone, either, as articles on anything from the architecture to why the fonts make its world feel way creepier attest.

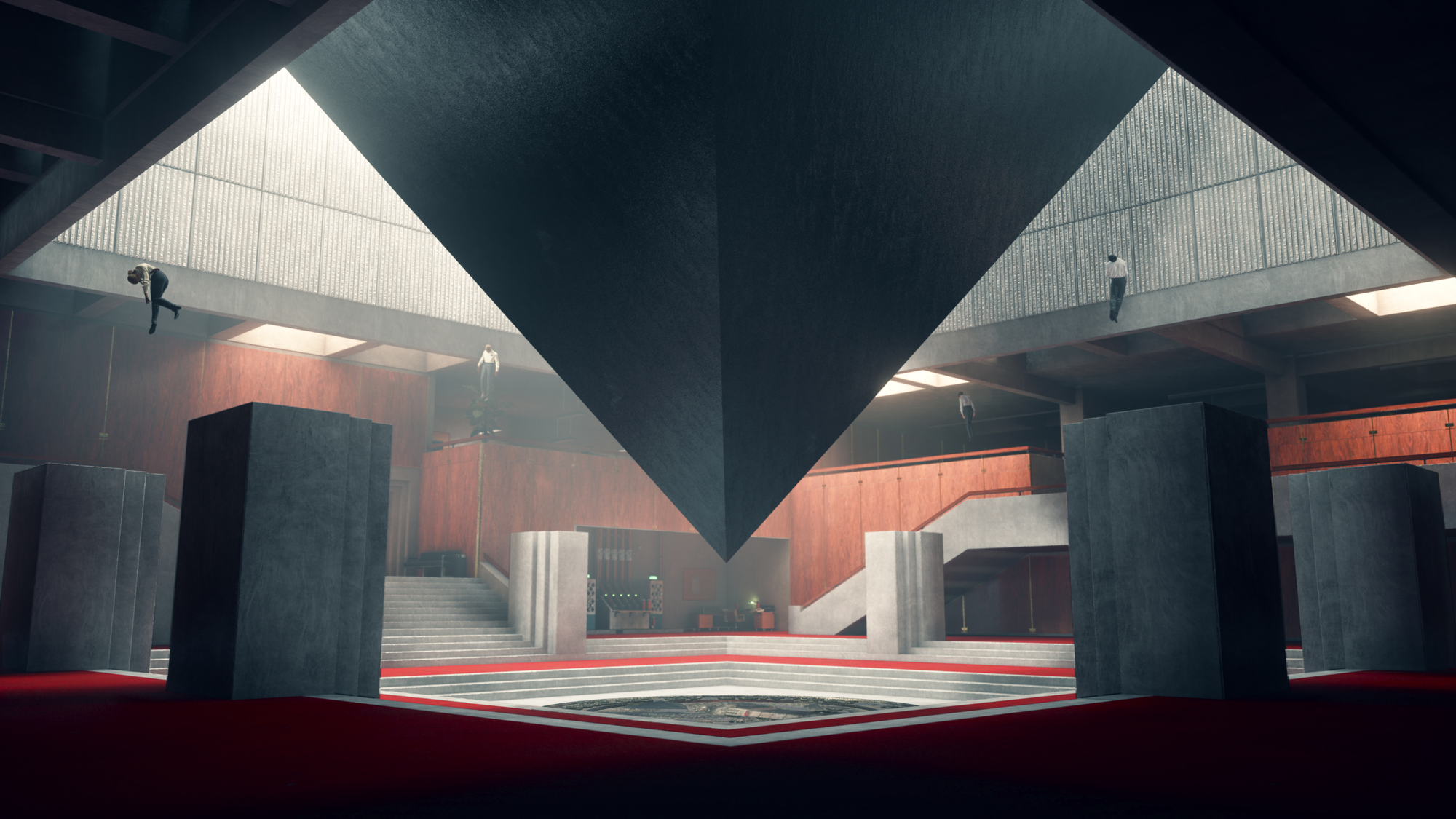

Put simply, location is everything in Control. On paper, The Oldest House is the New York based headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Control (from which the game derives its name in part). But in reality, it is so much more than merely a backdrop or canvas on which the core gameplay takes place. It may be a cliché, but The Oldest House is legitimately as much of a character in Control as the protagonist Jesse Faden.

The building’s architecture is both stark and imposing. It imbues a sense of uniformity while simultaneously exposing players to impossible structures and internal spaces which make you question the validity of anything you’re seeing. Walls, floors and ceilings physically shift and change as you make your way through the game’s story and discover new areas. From your first experience of the building, through to the Oceanview Motel and surreal expanse of the Black Rock Quarry, The Old House is as much study in the architectural uncanny as House of Leaves or The Haunting of Hill House and one Sigmund Freud himself would recognise his own thinking in. As he put it: “An uncanny effect often arises when the boundary between fantasy and reality is blurred, when we are faced with the reality of something that we have until now considered imaginary.”

It’s not just the fantastical nature of the building or its contents that made it have such a profound effect on me. In writing about the presence of the uncanny in fiction, the German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch wrote how “In telling a story one of the most successful devices for easily creating uncanny effects is to leave the reader in uncertainty whether a particular figure in the story is a human being or an automaton and to do it in such a way that his attention is not focused directly upon his uncertainty, so that he may not be led to go into the matter and clear it up immediately.” Sound familiar? This, for me, is what Remedy has done so well with its world-building and The Oldest House in particular. As a new player you automatically, unconsciously accept the environment for what it is on face value. But once you start to delve deeper, questions inevitably arise about the nature of this strange building set in a world which asks as many as it answers.

Luckily, given you’re highly likely to want to find out its secrets, it’s a game which also rewards exploration. From orientation films that would make the Dharma Initiative proud, to heavily redacted documents, there’s plenty of background information to be found among the corporate hallways and offices. Discoveries can also include additional combat abilities you won’t necessarily unlock if only following the main story quest. Which brings me to the issue at hand: the combat.

Before I go on, I should say that there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the combat in Control. Far from it, in fact. Engaging 'the Hiss' is fast-paced, frantic and chaotic, but also immensely satisfying. There are few joys equal to the thud and thwack of a lump of concrete slamming its way into an enemy while sparks and debris cascade all around you. As both an experience and visual treat, it ticks a lot of boxes. Levelling up Jesse’s abilities and power only makes it all the more enjoyable.

And yet, throughout my time playing Control I invariably found these cacophonic and bombastic firefights to be entirely at odds with the world I had invested so much in. You could argue these changes in tempo help propel you forward through the narrative. And it would be true, but only to a degree. When it came to reflect on Control, I couldn’t help myself comparing it to 2019’s remake of Resident Evil 2.

Like Control, the Capcom title relies on scene and setting to create much of its inherent tension. The Raccoon City Police Department building sits foremost in my mind as an example of this. The two titles also share Metroidvania-esque elements to their exploration and gameplay, as well as a tactical element (albeit in different ways) to their combat mechanics. But it’s here that the two games diverge quite drastically. In The Guardian’s review of the survival horror game, critic Keith Stuart described how “The rhythm, gradually building from many minutes of quiet exploration and puzzle-solving to gigantic, pulverising boss battles, is exact and beautiful, like some monstrous Wagner opera.” The same can’t, however, be said for Control.

That’s not to say it’s not a good game. It’s a great game, and one that in many ways is more affecting, creative and daring than Resident Evil 2. But for me, it also feels at times almost like two games merged into one. The origin of the term ‘uncanny’ is the German word ‘unheimlich’, translatable as ‘unhomely’ or the feeling of being ‘not at home’. The world of Control nails this feeling, but the combat itself — somewhat ironically — feels out of place, or not at home in it.

I constantly wanted to be able to sneak around the creepy surroundings, to pick and choose how to engage my enemy. As I played more I even began to feel slightly irritated by sudden outbreaks of attackers from multiple locations around me. All I really wanted to do was explore, discover and reveal.

With this said, Control remains a game I would wholeheartedly recommend. But it's the moments that revealed just a little bit more of the lore that binds the world together that I'll remember. And the quieter, unsettling atmosphere that will stay with me, long after the noise of combat has faded away.