D: Frustration as a Canvas

When frustration is the point

I don’t buy unobtrusiveness in my games. I like friction, I like having to think about what buttons to press, having to plan my movement, and wrapping my head around different means of locomotion.

It’s not that having a smooth experience is a bad thing, but the focus on user experience as the norm has hindered some possibilities, some elevation of truth, when the controller is supposed to just be a means to an end, and not an end in itself. There’s the argument of immersion (as in “if I feel the piece of plastic in my hands I remember that I’m just playing a game”). There is also the argument of game design (as in “the difficulty of the game should come from the challenges presented by the situations in which the player must traverse — cumbersome controls or animations hurt that challenge, as it then comes from external factors, outside of the fiction”), and the lack of argument altogether; it’s a convenience. L2 aims, and R2 shoots, so we don’t need to think about another system. Making games is already hard enough.

Every game is, at its core, a set of rules that you will use to interact with a space. Being an established fictional character or a faceless avatar doesn’t matter, as you are not them; you are their means of accomplishing things within that world. It’s surprising to me, then, that unless a game is specifically focused on being weird to control (usually for humorous purposes, like Getting Over It), said rules are not commonly bent when it comes to the interaction itself. Unless the cumbersomeness is the point, it's rarely an option.

It is, of course, understandable that people avoid the possibility of frustration. It's a forbidden sensation when it comes to art gazing. Fear and horror are not, adrenaline rushes are not, but frustration is, which is probably closely related to the feeling of losing time. There are so many things to see, watch, listen to, think about, read, and talk about that engaging with frustration is never desirable because you could've been engaging with pleasure instead. We already get a fair share of frustration on social media, so why is it leaking all over our entertainment too?

Existing outside of the spirit of the current age, D is a game that uses frustration in its movement for a very auteuristic and controlled experience. Every time you press an arrow, you'll need to wait for five seconds to press it again. You'll want to cancel animations. You’ll have enough time to change your mind during the movement but won't be able to. You'll dread your own thoughtlessness.

You see, there’s a time limit of two hours in D. Laura, the main character, goes to a hospital to investigate her father, who went on a killing spree. As soon as she gets there, she’s transported to a different world — something akin to a castle or a mansion. Her father appears in a vision, telling her that that world is her own mind. After two hours, she’ll get back to the “real world” and so will you, through a game over.

Existing outside of the spirit of the current age, D is a game that uses frustration in its movement for a very auteuristic and controlled experience.

There are a couple of layers for the interaction. We are not Laura, who is very much her own person. As Kenji Eno, the creator, described afterward, she is a digital actress, as she would be a different Laura in every subsequent game ([Enemy Zero, D2] but keeping her appearance), who is an actress exploring her mind to find things about her present and past but avoiding the future, within the time limit. She’s in a virtual world of her soul, and we are in a virtual world of ours, she’s an actress playing a role, and we are players playing a role of an actress playing a role of a character who’s exploring another role.

Why, then, would she move like we want her to?

Those layers would be mitigated if she had a 1:1 relationship with the buttons we press, so she doesn’t. D is an FMV game, which means Full Motion Video; every button press triggers a small cutscene of the character moving in that direction, or opening that drawer, etc. We suggest, on a macro level, what she should do: move left, for example. She won’t, then, move left. She will turn to the left and walk in that general direction, maybe straight ahead, maybe actually towards a door that is vaguely to the left, and when she gets to her destination, she’ll look around a bit. If we want to check a detail on her back, maybe we won’t be able to. Maybe she doesn’t have a “stop spot” there, and as you point her in that direction, she will just walk beyond it, and then we’ll need to go back to where we were, losing, sometimes, minutes in the process.

Laura has her own ideas on how to interact with that world in her mind. Rooms are not easily traversed, as sometimes we need to move her to the front and then to the right, even if the actual spot where we wanted to go was to the right of the first position. Pressing buttons within the world is, sometimes, a roulette, and other times, so slow you’ll risk a game over. You don’t know what pressing a direction will actually do, and you’ll be forced to handle her sensibilities and will. Maybe she will get to where you want, which is always exhilarating, but sometimes she won’t, so it becomes a puzzle in and of itself. How can I go back to that place in as few movements as possible? Every wrong press will eat your most precious resource: time.

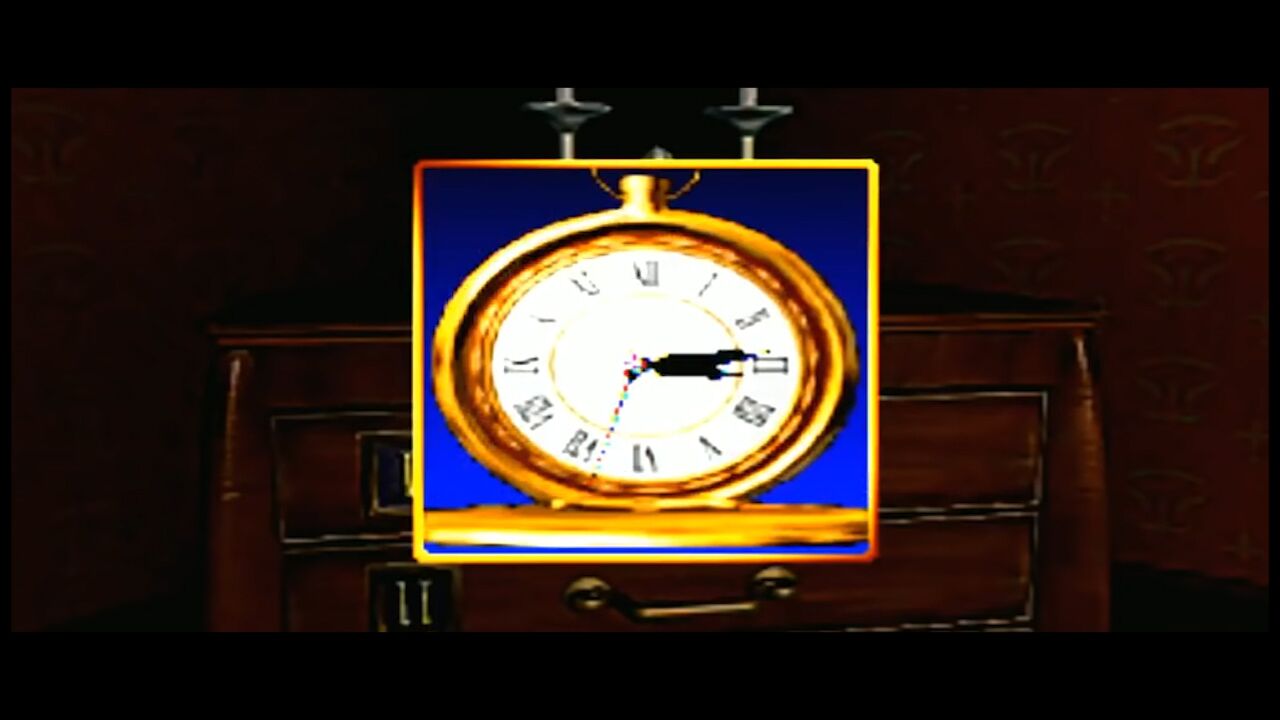

The clock, an item you can check in your inventory, never stops. It runs while you’re looking at it, but most importantly, it runs while you’re not. You don’t know how far in the game you are: the story is structured in such a way that it’s not obvious when you reach an “act”. Even the fact that the game comes on two CDs doesn’t make it that clear when you’re approaching the end. You’ll never know how many seconds you’ll lose if you press the left button, which will make you lose a different amount of time than if you pressed the up button. You’ll never know what parts of the setting are interactive, so even with that uncertainty you still need to try and explore, and fail, and maybe try again from the start. The game doesn’t have save points. You won’t go back to that dream from where you left off if you take another nap.

Inhabiting another person’s body is not something to be taken lightly and D understands that very well. I mean, inhabiting your own real body comes with a set of caveats, so inhabiting someone else’s, through the lens of technology, creativity, and ingenuity would be completely overwhelming. The game’s story slowly unveils itself and touches upon the same notions, but not as deeply as its gameplay does. It accomplishes that by not being afraid to surprise and vary its own rules; it risks frustration, but also delivers its message in a way that only a deeply curated, controlled, maybe even egotistical system could. You can never do something that wasn’t intended in D. Its systems do not allow flourishes or rhizomes, you can only do what the game was designed to let you do, and you can’t know what it's asking of you until you stumble upon it.

The conversation it has with the player is extremely one-sided. People accuse games like The Last of Us or the new God of War titles and their cinematic experience taglines as something that you only watch but said games have intricate exploration and combat systems that allow for system agency between their non-interactive moments. D doesn’t. but it is still, at its core, very clearly a video game, telling a story through a very idiosyncratic feeling that you get mainly from games: frustration, caused by lack of control, rule obtuseness, and having to handle someone else’s will.

Lack of control (as is the case with most things lumped into a description of "bad game design") is just a tool, and it can increase the potency of a message or create a mindset that might make a game even better through certain lenses. D is almost 30 years old at this point, and its lessons can create many more ripples if the consumers are up for it. It's much better to create more and more weird, experimental, and sometimes frustrating games instead of trying to discover a formula for a "perfect", formless, frictionless, sterile product.