Conspiracy, Prescience, and Deus Ex

Truth or conspiracy?

In late 1996, industry veterans John Romero (formerly id Software) and Tom Hall (formerly id Software and Apogee/3D Realms) founded Ion Storm. This studio would, in its brief existence, have an enormous influence on the games industry at the turn of the century - both positively and negatively.

Ion Storm's debut title, released in 1998, was the confusingly named Dominion: Storm over Gift 3, a middling RTS that couldn't hold a candle to contemporaries like StarCraft and Age of Empires. Dominion was not the third game in a series, but rather a spin-off of 7th Level's G-Nome, a mostly forgotten 1997 mech game that took place on a planet named Gift 3, hence the name.

Two years later and long overdue, Ion Storm released Daikatana, one of the most infamous game releases ever. The game was a new IP, a shooter from the mind of John Romero, and he had spared no expense hyping the title in the lead-up to its release. What was hyped and what was delivered were two very different things - Daikatana was a buggy mess, with dated design, a somewhat confused plot, and frustrating AI limitations. I would argue that the years have been kind to Daikatana, though, and there's a lot to love in hindsight.

It had been a horrific start for Ion Storm - a bland RTS followed by one of the most disastrous releases in gaming history. Things were looking bad for the ambitious studio, but Ion Storm's fortunes would suddenly shift a month later in June 2000.

What was hyped and what was delivered were two very different things - Daikatana was a buggy mess, with dated design, a somewhat confused plot, and frustrating AI limitations.

The God From the Machine

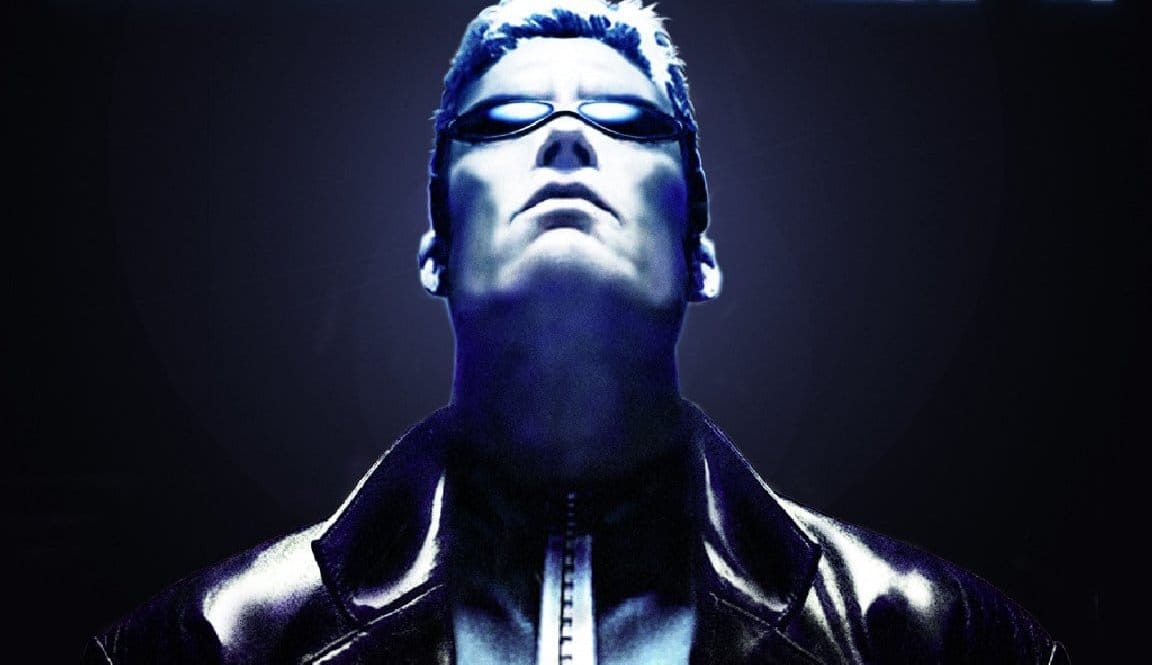

It is poetic that Deus Ex would prove to be the literal deus ex machina for the developer's reputation and legacy. Released a month after Daikatana, the development of Deus Ex was overseen by Warren Spector, who had joined Ion Storm in 1997 and founded a second office in Texas, this one in Austin.

Ion Storm's main office in Dallas, in the penthouse of one of the city's most prestigious towers, developed a frat-house reputation as the team of young game developers riding the wave of the Dotcom Boom rocketed past oil barons to the top floor, where they hosted all-night LAN parties, ordered copious amounts of pizza, and drank to excess.

From all accounts, Ion Storm's Austin studio sounded comparatively tame. Spector had joined Ion Storm from Looking Glass Studios after receiving an offer he couldn't refuse from Romero - the ability to produce the game he wanted, the way he wanted. Spector had been developing a reputation long before Romero and the scrappy id Software crew had hit the big time with Doom, and he'd played a pivotal role in the creation of the "immersive sim" genre with Ultima Underworld during his time at Origin Systems, and then with System Shock at Looking Glass. Many id developers, Romero included, have expressed how influential Ultima Underworld was to them in the creation of Doom.

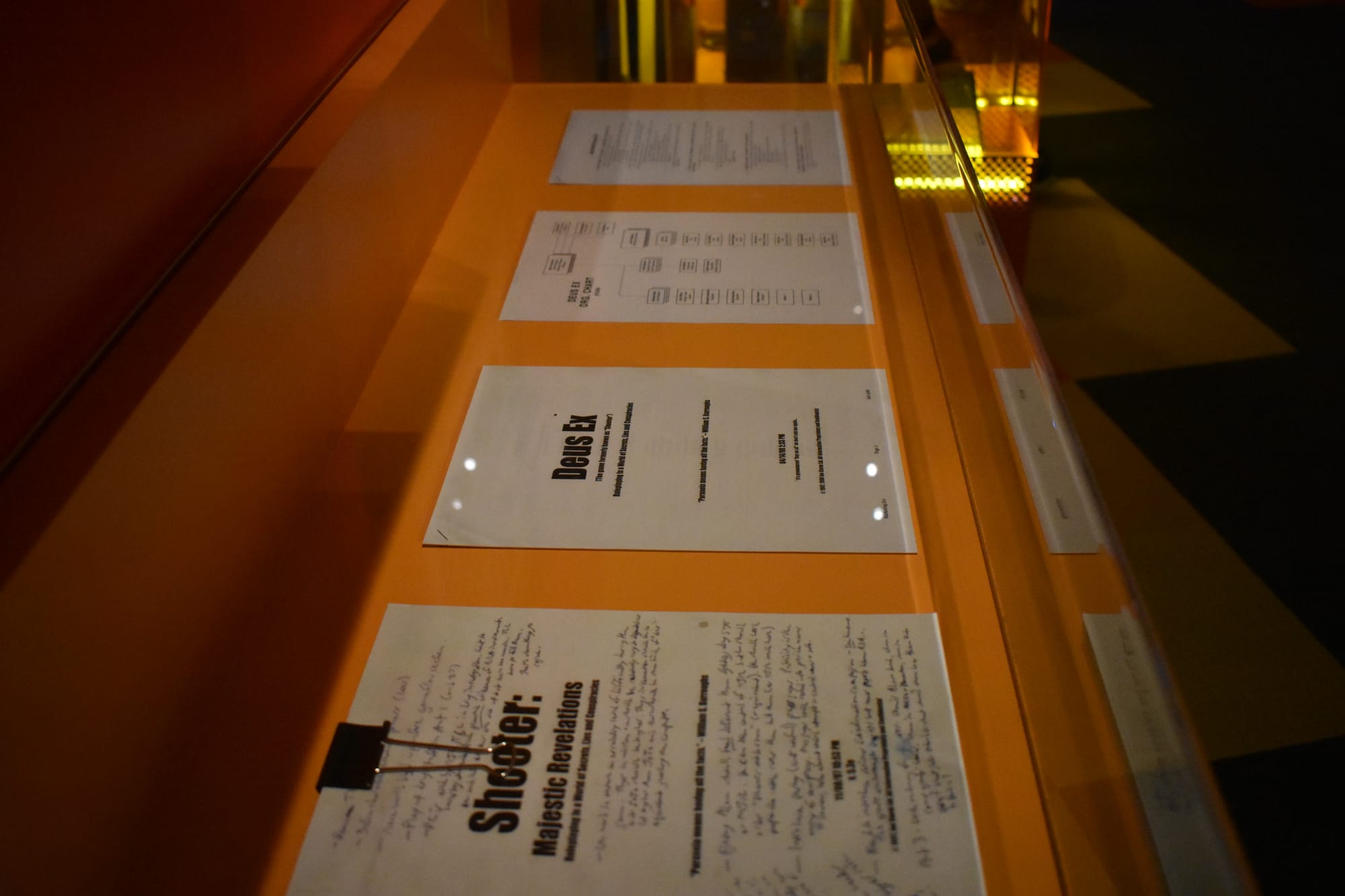

Spector's game, under the working title "Troubleshooter", commenced development shortly after the Austin team settled in. The concept had been circling through Spector's head since at least 1994, and he finally had the resources and freedom to pursue it. There was some skepticism from within Ion Storm at the slow progress, but Romero had faith in Spector and backed his creative vision.

Deus Ex was finally released in June 2000, just a month after Daikatana's launch had left Ion Storm's reputation in tatters. The reviews soon started to roll in, and it was immediately clear that Spector and his team had a hit on their hand; as the years have rolled on, it has become abundantly clear that "hit" is an understatement. Deus Ex redefined the gaming landscape in ways that few games had done before or have since.

Ion Storm's main office in Dallas, in the penthouse of one of the city's most prestigious towers, developed a frat-house reputation as the team of young game developers riding the wave of the Dotcom Boom rocketed past oil barons to the top floor, where they hosted all-night LAN parties, ordered copious amounts of pizza, and drank to excess.

A Product of Its Time

Deus Ex is the quintessential immersive sim. Though the definition of what that means continues to spark debate, the core elements are all there in abundance: Freedom, player agency, consequence, and systems that reward real-world problem-solving skills. However, it wasn't just mechanics that made Deus Ex shine.

It is hard to overstate the impact of the 1990s zeitgeist on Deus Ex. The game is infused with paranoia and conspiracy theories, of shadow governments pulling strings and mysterious "insiders" delivering cryptic messages of dissent. These themes didn't emerge in a vacuum - like all media and art, Deus Ex is a product of its contemporary culture.

It is increasingly difficult to conceptualise the world of the early Internet, but it was a time of both concern and anticipation. Never before had there been such ready access to information, such an easy way to share ideas. In this early Internet of bulletin board systems (BBS), chat groups, and eventually early websites, a subculture flourished. The rest of the world was slow to catch on - it would be many years before fact-checking websites, online encyclopedias like Wikipedia, or content regulation became the norm. Ideas spread fast, but discerning the truth was infinitely more difficult.

It was in this environment that the legendary TV show The X-Files emerged, hitting the small screen in 1993. The X-Files took a simmering post-Cold War subculture of conspiracy theory and deftly weaved it into a modern and infectious narrative about government overreach and shadowy G-Men pulling the strings that hold up the facade of reality. Computers and online culture would come to figure prominently in the X-Files, most notably in the Lone Gunmen, a trio of anti-government computer hackers that frequently helped Mulder and Scully throughout the series run (and even got their own short-lived spin-off show). The world that the X-Files emerged from was a cultural Lagrange point between the conspiracy-fuelled past of UFOs and the JFK assassination, and the post-modern future of vast, interconnected online subcultures, paranoia about climate change, the Y2K bug, and the looming rise of an increasingly powerful corporate aristocracy.

The X-Files was a cultural phenomenon, but it wasn't the only example of postmodern paranoia and existential anxiety. Unsolved Mysteries, airing from 1987 and famously hosted by Robert Stack, frequently delved into stories of UFOs, ghosts, and unexplained phenomena. In the West, anime rapidly found mainstream acceptance through film and TV like Akira, Ghost in the Shell, and Neon Genesis: Evangelion, each infused with a heady dose of paranoia and conspiracy. Cinema too, with Dark City, Johnny Mnemonic, 12 Monkeys, and of course the capstone to 1990s paranoid cyberpunk fiction, The Matrix. This is all, evidently, a distinctly Western cultural lens - it is the world I grew up in. However, as I hope I've illustrated thus far, while globalisation was quickening exponentially thanks to the emergence of the Internet, true global perspectives were still limited in scope and scale.

This is the world from which Deus Ex emerged. A world of lingering anxiety from the unsolved mysteries of its past, stuck in a rapidly changing and unpredictable present, and coloured with a vaguely hopeful yet notably paranoid concern about the future. Deus Ex, like so much art of its era, is a product of its time.

Conspiracy Theory All-Stars

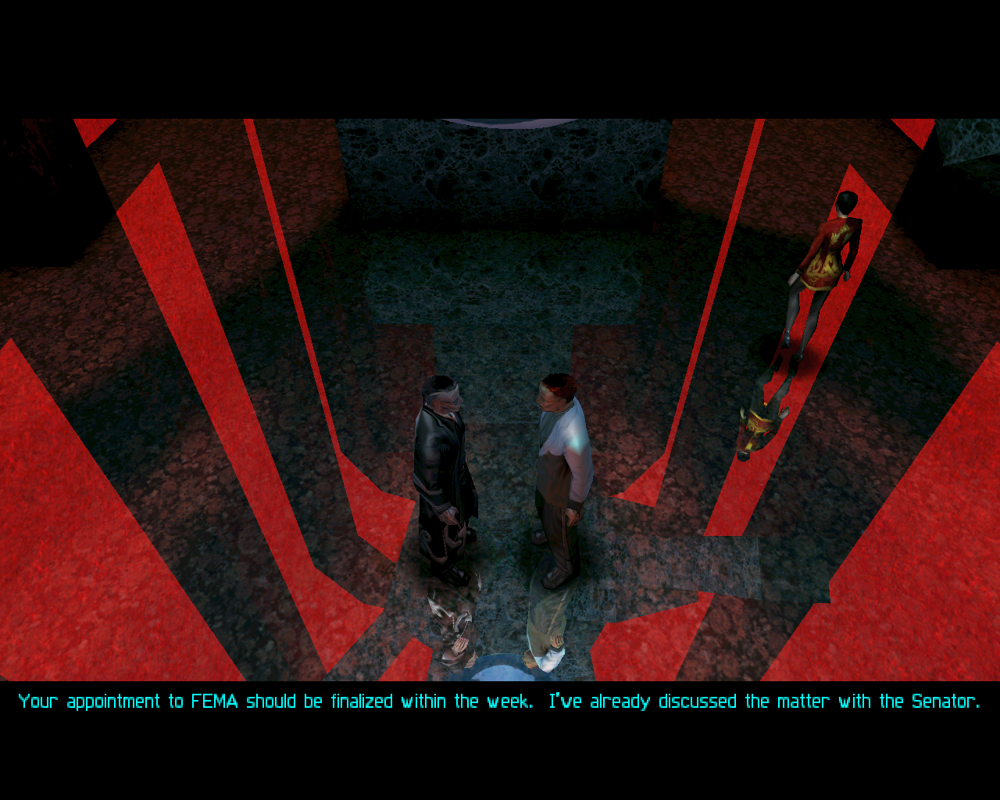

With 2025 hindsight and a bit of selective cherry picking, the plot of Deus Ex is eerily familiar. The year is 2052, and society seems to be teetering on the brink of chaos. Wealth inequality is at an all-time high, biomechanical and cybernetic implants are relatively commonplace, civil strife is rampant, and the world is wracked by a lethal global pandemic known as the Gray Death. Pharmaceutical company VersaLife controls the only known vaccine, and access is largely restricted to those higher in the social order. As the player delves further into the world of Deus Ex, they will uncover a dark conspiracy involving mainstays like the Illuminati, Majestic 12, FEMA, and of course, Area 51.

Deus Ex hit all the right cultural notes for the year 2000 - The Matrix was fresh in everyone's mind, The X-Files would finish its (original) run a year later, and the Y2K Bug had come and gone without much fanfare (or had it???). But Deus Ex wasn't just a culturally relevant game - it was a damn good game.

This is the world from which Deus Ex emerged. A world of lingering anxiety from the unsolved mysteries of its past, stuck in a rapidly changing and unpredictable present, and coloured with a vaguely hopeful yet notably paranoid concern about the future.

Deus Ex was praised for its free-form gameplay that represented the very pinnacle of the immersive sim genre to date. Gameplay systems were refined, tested, and polished. The first-person shooter DNA of Deus Ex is strong, and it is one of the best contemporary examples of the original Unreal Engine's capabilities, but this was far more than a linear run-and-gun shooter like Unreal, Quake, or even Half-Life. Unsurprisingly, with Spector's influence, Deus Ex felt far more System Shock and Thief: The Dark Project than it did Doom or Duke Nukem.

A Changing World

The 2003 sequel, Deus Ex: Invisible War, was a spectacular fall from grace. Due largely to hardware limitations imposed by an Xbox release, and quite possibly influenced by increasing strife at Ion Storm, Invisible War was poorly received. While not entirely dismissed, performance was criticised, and player agency felt, oddly, far more limited than its predecessor.

While not the primary subject of criticism, it should be noted that the plot of Invisible War was not highly regarded. You could argue that this is partly due to the benchmark being set so high by the previous game. But it is important to recognise that the world had changed immensely in the intervening years, and the catalyst was September 11, 2001.

Among the many consequences of that day was a marked shift in the mindset around state power and conspiracy. Much of the world rallied behind the US as it sought to respond to the horrific attacks, though perspectives on what constituted a proportionate response were vastly polarised. But societies did rally behind organised power - whether it was the political status quo or the political opposition. Conspiracy theories were rife too - but in the face of so many deaths, both during the 9/11 attacks and in the War on Terror that followed it, the idea of entertaining conspiracy seemed largely distasteful - many thousands of people had died.

Ion Storm closed its doors in 2005 after a troubled couple of years, and the studio's intellectual property passed into the hands of publisher Eidos Interactive, before passing to Square Enix following their merger with Eidos in 2009. Two years later, development studio Eidos Montreal released Deus Ex: Human Revolution.

Human Revolution was a stunning return to form. From a design perspective, it was a fresh and refined take on the original formula. Where Invisible War had struggled with its cross-platform release, the practice was now an industry standard, and Human Revolution suffered no such difficulties. The title was infused with the series' signature blend of cyberpunk conspiracy theories, but there were new themes now, with prejudice and inequality chief among them. Ten years on from the 9/11 attacks, society faced new challenges - a polarised world of war exhaustion and Islamophobic fear. While the thematic links with the zeitgeist weren't so overt as with Deus Ex, the influence is clear, especially in hindsight. One of the core themes of Human Revolution was fear and paranoia directed at augmented citizens, a sort of biomechanical racism.

Human Revolution was a stunning return to form. From a design perspective, it was a fresh and refined take on the original formula.

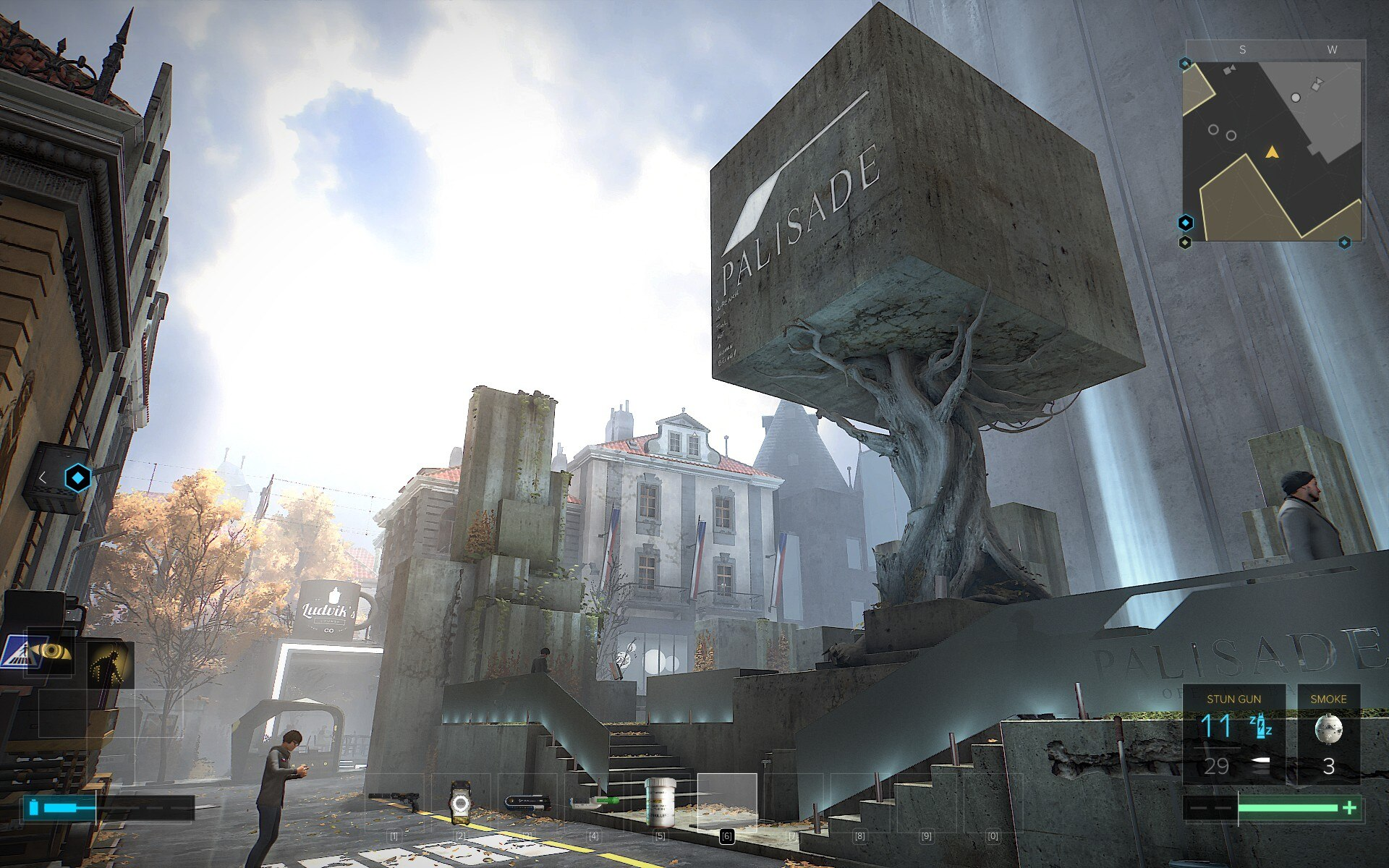

In 2016, Eidos Montreal further explored the story of Human Revolution protagonist Adam Jensen in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. This time, the themes were far more overtly influenced by issues of prejudice and race. Unfortunately, their handling was ham-fisted at best. Pre-release marketing used language like "apartheid" when describing the social divides in the world of Mankind Divided, drawing some critical commentary that the marketing was trivialising a very real and relatively recent tragedy. Even more tactless, Mankind Divided co-opted terminology and imagery used by the Black Lives Matter movement, with language such as "Aug Lives Matter" and the familiar raised fist - this time, a cybernetically enhanced one. It all felt a bit icky - these were and still are real issues with real victims, and a major studio co-opting those movements for financial gain felt unethical, and ironically, quite cyberpunk.

The game itself was actually very good - Mankind Divided is beautiful, and a very good example of what the limited open-world style of games like the Yakuza series can offer; what the game world lacked in size, it made up for in detail and immersion. Unfortunately, it ends just as it seems to be reaching a crescendo, and it is clear that Eidos Montreal was planning for a sequel that never materialised. Though it was actually quite good, Mankind Divided had been overshadowed by aggressive monetisation, most infamously with single-use DLC - one of the most idiotic and greedy decisions ever made by a game studio.

Mankind, Divided

The 2016 release of Mankind Divided coincided with the beginning of a tumultuous period of global politics. A new US president precipitated the beginning of a post-Truth era, with social media playing a defining role in the spread of misinformation and disinformation. This all culminated with the global coronavirus pandemic, and despite over 7 million confirmed deaths from the virus to date, real conspiracy theories flourished about the origins of the virus and allegedly malicious intent behind vaccines made to save lives. In this environment, spurred on by the monetisation of engagement by social media and harnessed for political clout by the powerful, conspiracy theories flourished.

A new US president precipitated the beginning of a post-Truth era, with social media playing a defining role in the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

The X-Files returned to TV from 2016 to 2018, and despite a handful of great episodes (Season 10 Episode 3, "Mulder and Scully Meet the Were-Monster", is an absolute treat), the new run had a mediocre reception. Like so many TV shows that return after a long hiatus, the key issue was that The X-Files no longer felt fresh or relevant. At the core of this was that The X-Files was a TV show that relied on the inherently captivating nature of conspiracy theories despite their clearly absurd foundations in reality.

The problem is that conspiracy theories had long since ceased being fun. Conspiracy theories are ultimately founded in the distortion of reality and misinformation, and as has become increasingly clear in the last decade, these concepts can have dangerous and sometimes lethal consequences. The same seemingly harmless individuals entertaining fanciful ideas about the moon landing and Y2K Bug were now finding success in discouraging people from taking vaccines and spreading racist theories about ethnic groups controlling government and media institutions.

It almost seems irresponsible to entertain conspiracy theories today, when the consequences of taking them seriously are so dangerous, yet there are always people who take them seriously. It's unfortunate, since reality has such great fodder for good conspiracy theory fiction - the idea that a shadowy global cabal had manufactured a virus in order to use a vaccine to control the population is a great basis for conspiracy fiction, and is actually quite close to some of the ideas in the Deus Ex.

Fiction Is More Than Entertainment

In 2020, Reed Berkowitz of the Curiouser Institute posted an article on Medium, A Game Designer's Analysis of QAnon. In the article, Berkowitz highlighted the strong links between various types of live-action games and the QAnon movement. Groups like QAnon co-opt popular strategies used in game design and marketing to drive interaction and engagement, heightening the sense of immersion by making the player feel like they are an integral part of a broader community and world. When used for nefarious purposes, these sorts of tactics are what draw otherwise rational people into exponentially more deluded and dangerous thought processes.

However, immersion is also what draws the player into the world of Deus Ex, to feel like you really are there in a dystopian world, uncovering the crimes of the powerful as part of the resistance. It speaks to an inner desire in us all, the same desire that drives those who fall into conspiracy theory thinking - to be the underdog, the hero, to be the one with impeccable values, who has the moral fortitude to stand up for them, and the insight to see the real truth of the world.

In either case, immersion is a powerful tool in communicating ideas. Games have, historically, not been particularly successful at driving social change, despite the fact that on paper, the medium seems to have all the right ingredients. Perhaps part of the problem is that games are still very much treated as an entertainment product.

The common refrain, especially since GamerGate, is "keep politics out of games". But "politics" has always been there. Fallout has a long history of tackling human nature and making statements on war, survival, and ethics. BioShock is a stern rebuke against the consequences of selfish libertarianism. Arcanum: Of Steamworks and Magick Obscura touches on many socio-economic issues, such as one quest where the player needs to decide how to handle a group of orcs attempting to form a labor union. And of course, there is Deus Ex, which from the start has highlighted the dangers of unchecked power, degradation of ethics in the name of technological progress, wealth inequality, and racism.

We may not see another game like Deus Ex, because the world that it portrays is now far too close to reality for comfort. But it does highlight an important issue - games are more than entertainment. They are reflections of the world in which they are made, and often have important things to say - as long as we listen.